Ancient Worlds: Apollo and Daphne

The title for Ovid’s Metamorphoses comes from the fact that every story he tells contains one. A metamorphosis, that is. While Homer begins his epics with Anger (in the Iliad and the Odyssey), Ovid begins In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas / corpora… “I’m of a mind to tell you about bodies changed into new forms…” Sometimes those changes are incidental to the story, but at the beginning, Ovid is interested in the big changes. The great, cosmic ones. He begins by telling about the first change, from yawning chaos into the slowly increasing order of Creation. He tells of the first four ages of mankind, the Roman version of the Great Flood myth, and of Apollo’s conquest of the great Python.

That last should be a good story, but he speeds past it: Earth Angry, Giant Dragon-Snake thing, God with bow, boom. Festival commemorating mighty victory. Next!

He then tells the story of Apollo and Daphne. The first thing you need to know is this:

Apollo has no game. None. Zero. He is That Guy. He is always That Guy, and the one time he manages to get a boyfriend, said boyfriend ends up instantly dead because Apollo is The Worst.

We have our theories on why that may be, but that comes later. For now, just know this: if Apollo is interested in someone, girl or boy, it will end badly for her or him. And probably for the world at large.

So when he comes into Olympus fresh from killing a dragon and makes fun of Cupid for being a baby archer… well, let’s just say that disturbance in the force that you feel is two-thousand years’ worth of readers cringing and then smacking their faces with their palms. Cupid, after all, enjoys making gods fall in love with really embarrassing people.

This time, however, he does one better, shooting Apollo with an arrow of desire while shooting Daphne, the daughter of a river god, with an arrow of disdain. Not that it was particularly necessary: Daphne had sworn off men. Like Apollo’s sister Diana, she wanted to spend her days roaming through the woods, single and childless.

This time, however, he does one better, shooting Apollo with an arrow of desire while shooting Daphne, the daughter of a river god, with an arrow of disdain. Not that it was particularly necessary: Daphne had sworn off men. Like Apollo’s sister Diana, she wanted to spend her days roaming through the woods, single and childless.

Unfortunately, Apollo had other plans. When he sees Daphne, he is instantly set on having her. A chase ensues, as do some ridiculous attempts to woo the fair maiden. He tries ‘Don’t you know who I am,’ and ‘I’m a doctor!’ and ‘Stop running so fast you might trip and fall and that would be terrible!’

Says the attempted rapist.

Did I mention Apollo is the worst?

When it looks as though Apollo will catch his nymph, she cries out to her father for help. He saves her from certain rape by turning her into a tree. The laurel tree, in fact, which is why a laurel crown is the symbol for victory in a number of ancient events. Apollo is heartbroken, Daphne is a tree forever, and Cupid is off somewhere cackling like the punk that he is.

The myth of Apollo and Daphne has inspired artists in all media ever since. The most famous example is Bernini’s sculpture, seen here. My favorite detail? Not only are Daphne’s hands leafing out, the bark has grown up around her flank so that when Apollo finally touches her, all he feels is a tree.

It’s a fantastic story, but why does it take such a central place in Ovid’s epic? Creation of the world, flood of world, establishment of most important cultural site in the ancient Greek world, and… Apollo strikes out on trying to get a girlfriend?

It’s a fantastic story, but why does it take such a central place in Ovid’s epic? Creation of the world, flood of world, establishment of most important cultural site in the ancient Greek world, and… Apollo strikes out on trying to get a girlfriend?

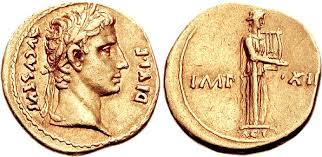

We can’t know for certain, but the going theory is that Ovid did it to tweak off the Emperor Augustus. Augustus routinely identified himself with Apollo in his role as the restorer of order, the god of light and healing and harmony. He had established the temple of Apollo Palatinus and the image of Apollo was frequently featured on Augustus’s coinage. In other words, the Emperor was a certified Apollo fanboy, and Ovid couldn’t resist pointing out that Apollo was an utter twink. While Augustus is creating a massive facade of myth and image to prop up the new regime, Ovid is sticking out his tongue.

That alone makes him an artist worthy of further study, not to mention emulation.

Why Apollo and Daphne so soon? I didn’t know about the political satire angle, and that makes sense. But maybe also because one of the main drivers of transformation in the book is sexual violence, and Ovid wants to bring that in early.

When I first read Ovid, I was 11 years old. What was my mother thinking, handing an 11 year old a book with that many rapes in it? I still don’t know. In any case, I had in the previous year read the Iliad (women as spoils of war), and the Odyssey (Penelope’s servant women butchered by Our Hero for having failed to resist the suitors on their own — murdered for being rape victims). The Authors Usually Called Homer don’t much ask themselves what the women’s perspectives would be. Ovid asks himself all the time, and because he’s telling so many stories, he doesn’t reduce those perspectives to something monolithic. For some characters it’s a fate worse than death, or at least a fate worse than tree, but for others it’s something to be survived so they can demand that their assailants make amends by turning them into men. And for others it’s something to be avenged in blood. The women are individuals, despite being subjected to or threatened with with same wrong.

I’m no classicist, so this may be my ignorance of Roman context, but Ovid’s imaginative sympathy seems surprising, even anomalous. Is it?

I am embarrassed to have not thought of that, Sarah! And yes, you’re dead right: Ovid is anomalous in a number of ways in his portrayals of love, sex, and women, and most especially the ways those interact. I was just thinking that issue deserves a post of its own, probably in relation to Caenis? And possibly next week, since its a touchstone he keeps coming back to.

Part of it is his role as an elegiac poet: elegists are famous for playing with gender roles and centering women in their narratives, mostly as objects of desire but also as fleshed out characters all their own. But Ovid really takes it further. His sexual politics aren’t ours, exactly, (he has a really disgusting ‘no means yes’ bit in the Ars Amatoria that makes me want to slap him silly, but it reads more like Mad Men era chauvanism about false modesty than a lack of regard for consent). But he says things that are REALLY striking for a man of his period.

For example, we know he was strictly (what we would call) heterosexual. Which is interesting form a purely biographical standpoint, but also because he gives his reasoning: he has no interest in a pairing in which both parties aren’t going to thoroughly enjoy themselves.

There’s a whole lot of sociology packed into that statement, clearly, but I think it says a lot about the way he thinks.

I think above all, Ovid really :likes: women. He seems to view them as people. It is sad that this was revolutionary, and even sadder that this is still often the case today, but it sticks out.