Beyond Ever After: Into the Woods

Whenever I walk into my local chain bookstore, I am immediately attracted to a display near the entrance which bears the enticing banner, “Former Bestsellers.”

Whenever I walk into my local chain bookstore, I am immediately attracted to a display near the entrance which bears the enticing banner, “Former Bestsellers.”

Here reside the Grishams, the Clancys, and the Kings of last year and the year before, pushed off the pedestal of the New and the Now by the never-ceasing flood that issues from the mouth of modern publishing. It is a great place to grab a good read, cheap.

It is, alas, the fate of even the most successful book to eventually become a “former.” A quick consultation of the New York Times bestseller list reveals that the number one hardcover fiction book of this first week of 2015 is Gray Mountain by John Grisham. It is, I am sure, an efficient and effective novel, but if we could leap forward two or three hundred years and conduct a cyborg-on-the-street interview, what is the likelihood that any of our subjects would be able to name the characters or recount the plot of Gray Mountain?

Of course I’m being unfair to Grisham, a writer who is a straightforward, popular entertainer of the moment with no aspirations to membership in the Pantheon. Might we do better asking our 24th century citizen about A Farewell to Arms, or Lolita, or Portnoy’s Complaint? Yes? Umm… no, I think.

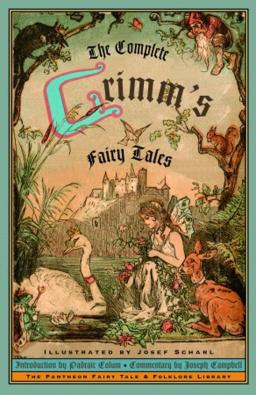

What could we ask about with any chance of success — never mind centuries from now, but even today? (Outside the halls of the English Department, I fear that the great works of Hemingway, Nabokov, and Roth wouldn’t fare any better than Forever Amber — and if you’ve never heard of that one, that’s my point, and if you have… oh, just sit down and be quiet!) Here’s a guess — Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood, Rumplestilskin, Hansel and Gretel, stories that were already old when Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm first collected them two hundred years ago.

Why? Why do we — almost all of us, young and old, rich and poor, even in an age of blurring speed and instant obsolescence — still know these old, old, stories? It is certainly not because of their simplicity; try writing a detailed summary of Snow White or The Elves and the Shoemaker and you’ll realize what complex and intricate narratives they are.

Perhaps these tales endure because they still unashamedly speak to us of essential, permanent things, of life and death, of love and loss, of truth and falsehood, of courage and cowardice, of sacrifice and selfishness, of (dare I say it?) good and evil, and they do so unencumbered by the distractions of even trying to be hip or up-to-date. Their appeal is as deep as their function is essential; fundamentally, they still reach us because they still teach us.

Perhaps these tales endure because they still unashamedly speak to us of essential, permanent things, of life and death, of love and loss, of truth and falsehood, of courage and cowardice, of sacrifice and selfishness, of (dare I say it?) good and evil, and they do so unencumbered by the distractions of even trying to be hip or up-to-date. Their appeal is as deep as their function is essential; fundamentally, they still reach us because they still teach us.

In his preface to Aesop’s Fables, G.K. Chesterton makes the same point about the stories of the eponymous Greek slave. He says,

In this language, like a large animal alphabet, are written some of the first philosophic certainties of men. As the child learns A for Ass or B for Bull or C for Cow, so man has learnt here to connect the simpler and stronger creatures with the simpler and stronger truths. That a flowing stream cannot befoul its own fountain, and that anyone who says it does is a tyrant and a liar; that a mouse is too weak to fight a lion, but too strong for the cords that can hold a lion; that a fox who gets most out of a flat dish may easily get least out of a deep dish; that the crow whom the gods forbid to sing, the gods nevertheless provide with cheese; that when the goat insults from a mountain-top it is not the goat that insults, but the mountain; all these are deep truths graven on the rocks wherever men have passed.

What is true of these ancient Greek fables is also true of the folk stories and fairy tales that form one of the keystones of our civilization. It is easy to forget from our information-rich vantage point that these tales were not originally confined to the nursery, but were an important part of the lives of adults living in times and places where literacy was rare, and as Chesterton perceived, they were a vital means of preserving and transmitting the knowledge and wisdom that creates a culture and constitutes a heritage. (They were also surprising, suspenseful, swiftly-moving, stimulating, even often violent or gruesome or shocking. In short, they were — and still are — entertaining.)

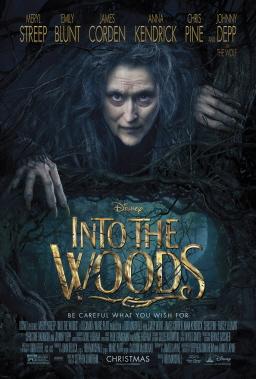

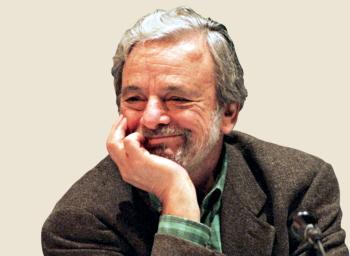

The enduring teaching power of these stories was surely one of the things that attracted the composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim, and convinced him that they could make a sound basis for a Broadway musical. Sondheim has often spoken about his reverence for teaching. Indeed, he has said that in his view, “all art is teaching.” He had already ventured into the area of the legendary and the (literally) fabulous with 1979’s blood and brimstone-laced Sweeney Todd, and in 1987, working with librettist James Lapine, he ransacked the Brothers Grimm and wrote Into the Woods.

In Into the Woods, Sondheim and Lapine take four classic tales — Cinderella, Rapunzel, Jack and the Beanstalk, and Little Red Riding Hood — and ingeniously use their own characters of a childless Baker and his Wife to connect all of the separate threads and take the stories past the “happily ever after” endings that we’re familiar with.

[Warning — spoilers ahead.]

The Baker and his Wife happen to live next door to a Witch (no redlining in Fairyland) — the same Witch who keeps Rapunzel locked in her high tower — and discover that they are childless because the crone has cursed them with barrenness in retribution for the transgressions of the Baker’s long-fled, feckless father, who had stolen from the Witch’s garden. The Witch tells them that if they perform a task for her, she will remove the curse and they will be able to have a child.

The Baker and his Wife have to collect four items — a cow as white as milk, a cape as red as blood, hair as yellow as corn, and a slipper as pure as gold. The Witch can use these ingredients to make a potion that will restore her to youth and beauty; that done, she will then grant the couple’s wish for a baby.

The play’s first act depicts the working out of this story, as the hapless pair venture into the mazelike forest and comically cross paths with Jack, Little Red Riding Hood, Rapunzel (“Rapunzel — what kind of a name is that?”), and Cinderella, talking or tricking them out of the needed items, gaining one and then losing another and stumbling about at cross purposes in an arboreal equivalent of the constantly opening and closing doors of a bedroom farce. Finally, the act ends with all of the items collected, the Witch appeased and transformed, the curse lifted, and the four original fairy tale protagonists each given their traditional “happily ever after” ending.

Life differs from fairy tales, however, in that there is often a second act, beyond ever after, in which we come to understand what our sometimes reckless wishes really involved. In the second act of Into the Woods, the wife of the giant slain by Jack climbs down a second beanstalk (the result of a carelessly discarded bean), seeking revenge for her husband’s murder. In attempting to find Jack, she demolishes the village, destroying the Baker’s house and killing Red Riding Hood’s grandmother. The characters flee back into a now more threatening forest; many of them will not reemerge, and those that do will be permanently changed.

The Witch is in favor of turning Jack over to the Giantess; the others agree and disagree and quarrel and make accusations and trade blame. Jack’s mother is accidentally killed by an inept royal steward; a panicking Rapunzel is trampled by the Giantess; the Baker’s Wife becomes lost in the woods and is seduced by Cinderella’s Prince. Shortly after he leaves her, she too is killed by the Giantess, in a sexual transgression-retribution formula as merciless as that found in any teen slasher movie.

Upon receiving the news of his wife’s death, the overwhelmed Baker gives his infant son to Cinderella and flees deeper into the forest where he encounters his father, whom he had believed dead. His father, trying to save his son from repeating his own mistakes, convinces him that running away is no solution. The Baker returns to the others and formulates a plan to defeat the Giantess, and working together, they save what’s left of the kingdom by killing her.

In the aftermath, they decide that the orphaned Jack and Red Riding Hood will come and live with the Baker, to be joined by Cinderella, who will not return to the palace. (The Prince explains his infidelity by telling her, “I was raised to be charming, not sincere.” Not surprisingly, she is unmoved by this logic.) A new family forms to continue the nurturing work of the old, and even after the maledictions of Witches and the incursions of Giants, life goes on.

Despite the darkness of the second act, Into the Woods was a solid Broadway success, running for almost two years, and winning three Tony Awards, including best book and best score, and it has been successfully revived several times since its original run. A stage performance with most of the original Broadway cast was broadcast on public television in 1991, but the news that the play was to be made into a full-scale movie was greeted with trepidation by many fans of the musical, especially in light of the uneven 2007 film version of Sweeney Todd.

The film of Into the Woods released by Disney on Christmas Day has proven most of those worries to be groundless. The original play is largely intact; James Lapine did the script from his own libretto, and the music of Stephen Sondheim is still the music of Stephen Sondheim. Unlike Tim Burton, director Rob Marshall apparently has the radical notion that the first requirement for a lead role in a musical is the ability to sing, and all of the principals sing their songs very well indeed. Anna Kendrick as Cinderella, with with her crystal-toned soprano, is an especial delight, and “Agony,” the histrionic duet of self-pity sung by the two spoiled princes (Chris Pine and Billy Magnussen) is a hilarious highlight.

My main concern was not with any of the major roles, but with a minor one. At this point in human history, Johnny Depp is a force that can only be contained rather than eradicated; like certain natural disasters, limiting the damage he does is often the best that can be hoped for. The people in charge this time around seemed to know this, and Depp’s screen time as the Wolf is as short as his one song is undemanding; he offers his particular brand of excess and then goes away. After Sweeney Todd, that is a major relief.

The lack of the act-break intermission of a live performance combined with a bit of end-of-act-one and beginning-of-act-two trimming by Lapine makes the transition between the “light” first half of the movie and the “dark” second half a bit abrupt, but I imagine that will be more of a problem for those unfamiliar with the play than it will be for those who already know that the shift is coming.

The only real loss I felt was the disappearance of the song that the Baker (the fine James Corden) sings when he runs away from his responsibilities; “No More” is one of Sondheim’s most beautiful and moving songs. As it is a duet between the Baker and his long-lost father, its elimination was likely necessitated by the fact that the character of the Father is all but eliminated from the film. Still, it’s a shame to lose such a wonderful number.

That minor quibble aside, Into the Woods is an excellent version of the play, and does an admirable job of conveying the divided essence of the original work. It is, as I have said, very well sung and acted by a first-rate cast; in addition to those I’ve already mentioned, Meryl Streep as the Witch and Emily Blunt as the Baker’s Wife handle their roles with assurance and flair. The look of the classic medieval European Fairyland is nicely done — there are no surprises in the visualization, but with this kind of archetypal material, familiarity is a virtue.

Most pleasingly (and perhaps surprisingly, given his helming of Pirates of the Carribean: On Stranger Tides), Marshall doesn’t go overboard with the CGI. It is used, and used effectively, in the places where it can best serve the story, as in the transformation of pumpkin and mice into Cinderella’s carriage, and in the castle-crumbling rampage of the Giantess, but in these and the other places it is employed, the CGI never becomes the point of the scene.

Marshall clearly knows that the heart of his movie lies in the characters and their human dilemmas, and especially in the music that brings them to life. Even with the effects, fantasy spectacle on the order of Peter Jackson’s Tolkien films is not what is being offered here; instead the effects are used with restraint, as a counterpoint to the simple moments of grief and fear, expectation and joy, in order to highlight those moments and make them stand out all the more. There are giants in Into the Woods, but the scale of the picture is kept blessedly human.

The changes made in the original tales mean that Into the Woods, despite the aegis of Disney, isn’t a story for children — or not for children alone, anyway. The sudden deaths and conflicts and questioning among the “good” characters (to say nothing of the waywardness of the Baker’s Wife) mean that many children will best see the film accompanied by adults who are prepared to answer questions afterward, though the grown-ups may wind up crying out with the Baker, “Stop asking me questions I can’t answer!”

Some people may have problems with the film’s change in direction, as many did (and still do) with the second act darkening in the original play. After all, isn’t the “happily ever after” a vital part of these tales — perhaps the most vital part? Isn’t the promise, in the words of William Faulkner, that “man will not merely endure: he will prevail” the whole point? (Indeed, Sondheim and Lapine may have felt the justice of the question, for they have sanctioned a “junior” version of the musical, meant to be performed for younger audiences, that contains only an edited first “happy ending” act.)

One of the things that makes a work of art living and vital is its ability to be expanded, reinterpreted, and utilized anew by each new generation; works too rigid to accept such sometimes rough handling don’t last the way the great fairy tales have lasted. The old stories are certainly strong enough to take a bit of modern tweaking, and actually, how much has truly been changed in Into the Woods? Is the picture painted really so bleak? People have died, but human connections and sympathy have not; houses have been destroyed, but home as it is embodied in human love and support still exists and is worth fighting for.

“I’m not perfect; I’m only human,” Cinderella’s Prince says, to explain his straying. As an excuse, that may or may not be acceptable, but as a description it is inarguable; we are all only human, all of us sojourners in the woods, making our wishes, groping for the magical items that we imagine will unlock our happiness, all of us fallible, foolish, weak, fearful, more or less blind. But the old tales and the new both recognize that the losses and the failures are not the only or even the essential story. The greatest truth is that some battles are won; some faiths are kept; some loves endure.

As Into the Woods ends, the shade of the Baker’s Wife returns to sing her counsel, as her widowed husband ponders how he will raise his child in a world without her:

Sometimes people leave you / Halfway through the wood / Do not let it grieve you / No one leaves for good / You are not alone / No one is alone / Hold him to the light now / Let him see the glow / Things will be all right now / Tell him what you know

And so the Baker begins to tell his infant son the story, commencing the task of teaching that never ends as long as life lasts. “Once upon a time, in a far-off kingdom, there lived a young maiden, a sad young lad, a childless baker with his wife…” After feeling helpless in the face of circumstance, he finally understands that he, like everyone else, is a character in a story that he is writing himself, and while darkness does exist, it is not absolute. As the Baker begins rebuilding his life by reciting his story, the gloom of the woods is dispelled by the morning’s rising sun.

In one form or another, these stories that have lasted for so long will continue to cast their spell, because they belong to us all; collectively they tell the story of all our lives. Into the Woods, as a play and as a film, is merely one more variation on their deep and timeless themes, but that it was made at all, in this second decade of the twenty first century, is a testament to the continuing power and vitality of the old tales that are its source.

The craft and intelligence that went into its creation make Into the Woods a worthy link in a chain that stretches back half a millennium and more, and that extends into the future as far as we can see, until it is lost from view, hidden by the forest and its trees.

Glad to hear a positive review. I’ve been avoiding this one, honestly. Very few pieces crafted as theater make a successful transfer to the screen. Exceptions abound, of course, but I feel confident in saying they prove the rule. That said, I can see Into the Woods doing well on the silver screen. For one thing, it’s got an awful lot of locations. The last time I saw it performed live, it was done on a rotating stage, the better to handle the swift “set changes” (mostly accomplished via the audience’s imagination, even then).

I agree with you about Johnny Depp. An actor of great promise once, now convinced that his every eccentricity is godlike, divine.

Into the Woods, to milk the cow!

Really, I felt a bit bad about my swipe at Depp. (Not bad enough, I guess!) He’s not the one I blame for Sweeney Todd; he did the best he could with a role he was unsuited for. Tim Burton is the one who carries the blame for that fizzle. (It’s one role where Depp’s over-the-top tendency could have served him well, but he couldn’t go for it because he couldn’t sing the way the part requires.)

Well, I recognize FOREVER AMBER! (It might even show up as one of my Old Bestseller reviews one day …)

I liked INTO THE WOODS a lot. I agree that it was a relief that Depp was gone so quickly. That said, I was apparently the only person who really enjoyed SWEENEY TODD. And while Depp’s recent substitution of tics and exaggerations for acting is a shame … he’s done a lot of truly excellent stuff, all the way back to EDWARD SCISSORHANDS.

(I like the movie version of A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC too, though I miss all the songs! [grin])

Good review!

—

Rich