My City’s Heroes (Part 1 of 2)

There’s a post I’ve wanted to write for this site for some time. I wasn’t sure exactly how to approach it, but I knew the general subject. I’d thought it’d fit here because it would be about myth and heroes. About stories and storytelling, and about the importance of story. In the wake of recent events I’ve come to feel the time has come to finally write that post. So here, on the shortest day of the year, are a few words about legends; about those that bear a torch through the longest darkness and inspire us to follow them. About heroes, in reality and in stories. And about the Montréal Canadiens.

There’s a post I’ve wanted to write for this site for some time. I wasn’t sure exactly how to approach it, but I knew the general subject. I’d thought it’d fit here because it would be about myth and heroes. About stories and storytelling, and about the importance of story. In the wake of recent events I’ve come to feel the time has come to finally write that post. So here, on the shortest day of the year, are a few words about legends; about those that bear a torch through the longest darkness and inspire us to follow them. About heroes, in reality and in stories. And about the Montréal Canadiens.

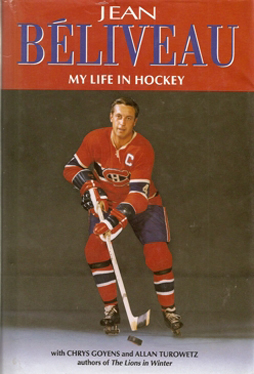

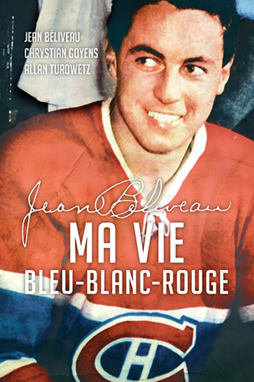

Jean Béliveau died on December 2 at age 83. He played for the Montréal Canadiens hockey franchise for eighteen full seasons, and won the Stanley Cup ten times. He was the team’s captain from 1961 until his retirement after winning the Cup in 1971. I’m not going to get into his career statistics — though they are impressive, enough so to put him in conversations about the greatest player of all time — because the numbers aren’t really the reason I’m writing about him here. I’m writing about him because beyond being a hockey player, he was, by any measure, a legend. And what I mean by that is that beyond the facts of his career, he was — is — a man about whom stories are told. And these stories have a common theme.

As I write the first draft of this post, I have the live broadcast of his funeral on TV; it’s being carried in both French and English. I’m seeing figures from beyond the world of hockey: past and present Prime Ministers and Premiers of Québec are filling Cathédral Marie Reine-du-Monde as, amid the grey of a major snowstorm, a crowd lines the street outside. Commentators are recalling stories about the man. The most telling stories aren’t about Béliveau’s remarkable scoring talent. They’re about his grace, kindness, and instinctive nobility: the guidance he gave to other players, the charisma of his presence, even simply the man’s smile and the time he gave freely to perfect strangers. As much or more is said about the man’s life after he retired from hockey as it is about his career. This is not surprising to me. I’ve been hearing Jean Béliveau stories all my life.

This may be my favourite Béliveau story, recorded by journalist Brian McFarlane in his book The Habs. The speaker is Dennis Hull, who played for the Chicago Blackhawks, recalling a game in 1964. As he tells it, Beliveau had a clear path to the Chicago net:

I hustled over as fast as I could and I laid the lumber on him. I hit him as hard as I could with my stick, right across the arms. But Béliveau kept moving and flipped the puck in behind [goaltender Glenn] Hall for a goal.

Then he wheeled around the net and came right up to me. He gave me a look — I’ll never forget it — and said, “I did not expect that kind of thing from you, Dennis?” He looked so hurt and disappointed in me that I felt like hiding under the logo at centre ice. I chased after him and apologised. “Geez, I’m sorry, Jean. I’ll never do that again.” He didn’t look back and I wasn’t sure he heard me so I said it louder. “Jean, I’m really sorry. It won’t happen again.”

Meanwhile Billy Reay, our coach, wanted to know what the hell was going on. I told him I was apologising to Jean Béliveau.

“Jesus, you don’t ever go around apologising to guys,” he snorted.

I said to him, “But that’s Jean Béliveau. One of my boyhood heroes.”

Billy glared at me and said, “What the hell does that have to do with anything? You never apologise.”

I said, “Okay, Billy.” But I was glad I did apologise because I felt awful about hitting Béliveau with that two-hander. It was the first and last one he ever got from me.

My other favourite Béliveau story is simpler. From a book called More Slapshots, by Stephen Cole:

The tall, elegant centreman’s graceful play and regal bearing came to embody all that was virtuous and noble about le-bleu-blanc-rouge [the Canadiens, so nicknamed from their team colours]. Once after a game, a rookie Canadien, unhapy with his play, threw his jersey away in disgust. Béliveau walked over and carefully lifted the jersey from the floor. “This sweater,” he said gravely, “never lands on the floor again.”

Both stories are about right behaviour, and about Béliveau’s ability to recall to people what behaviour is right and fitting. To bring to mind values that they know to be right, but which under stress they had forgotten. Look at the first sentence of the second story, and look at the adjectives: ‘graceful,’ ‘regal,’ ‘virtuous,’ ‘noble.’ Those are the kinds of words that turn up in the best Béliveau stories. Those things are what the Béliveau stories are about.

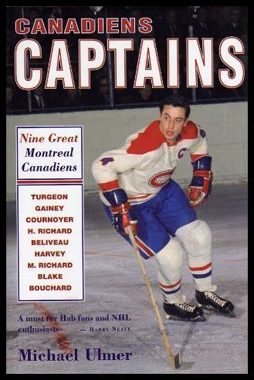

The Montréal Canadiens are the oldest franchise in the National Hockey League, predating the foundation of the League itself. It’s become something of a truism to say that they’re the most storied team in the NHL, which is my point here: that they are storied. And the stories we fans tell about the team and about the players are, like any stories, told and retold in part because they embody themes; because they communicate values. Over the years the team has had many great players. The best players, like Béliveau, become not just heroes but myths: symbols of imporant virtues.

The Montréal Canadiens are the oldest franchise in the National Hockey League, predating the foundation of the League itself. It’s become something of a truism to say that they’re the most storied team in the NHL, which is my point here: that they are storied. And the stories we fans tell about the team and about the players are, like any stories, told and retold in part because they embody themes; because they communicate values. Over the years the team has had many great players. The best players, like Béliveau, become not just heroes but myths: symbols of imporant virtues.

The most memorable stories about Maurice Richard are about determination: how he exhausted himself helping his brother move, then went out to play that night and scored eight points. The stories about Guy Lafleur are about flair and style, scoring the big goal at the right moment. The stories about Béliveau are about nobility, and how to deal with others. These are legends, serving the purpose that legends have always served. To present examples; models for behaviour. To present heroes. Not everyone can become a legend, and those who can aren’t always legendary at every moment. That’s not the point. The point is that the story is there, being told. The hero’s act becomes extracted from time, even from reality, and crystallises as story, as fable, as myth. The stories are true; but the truth of them is only a part of their power.

Hockey as a sport is both incredibly important to Canadian culture and also an odd exception. Anglo-Canadian culture in particular has a tendency to resist myth and the mythic, a tendency to turn away from the fantastic and metaphoric. Except when it comes to hockey. The game’s brutal, filled with bullying and cheap shots; it’s a game that’s usually defined by who makes more mistakes than the other team; and yet for all that, there’s a romanticisation of hockey across the country. Sure, the Canadian mythic imagination seems to argue, hockey’s filled with pain and mistakes — but that’s what life is, isn’t it?

Hockey’s a large part of Canadian lore. It is a metaphor in our songs and stories, a way to speak about our values. It is the subject of our children’s tales, and celebrated on our money. One story has it that a hockey riot triggered the phenomenon of modern Québec nationalism, and so deeply affected the shape of the political conversation of the nothern half of the North American continent for the past fifty years and more. Certainly in 1972 hockey provided one of the great shared moments in Canada’s history, as TVs were brought into workplaces and schoolrooms to watch the final game of a series between Canadian and Soviet national teams. In 2010 the Olympic gold medal game between Team Canada and Team USA generated the biggest TV audience in Canadian history, and, when Canada won in overtime, created a moment of coast-to-coast-to-coast celebration. The stories generated by hockey, fables of figures larger and stronger and swifter than life, are central to Canada.

Hockey’s a large part of Canadian lore. It is a metaphor in our songs and stories, a way to speak about our values. It is the subject of our children’s tales, and celebrated on our money. One story has it that a hockey riot triggered the phenomenon of modern Québec nationalism, and so deeply affected the shape of the political conversation of the nothern half of the North American continent for the past fifty years and more. Certainly in 1972 hockey provided one of the great shared moments in Canada’s history, as TVs were brought into workplaces and schoolrooms to watch the final game of a series between Canadian and Soviet national teams. In 2010 the Olympic gold medal game between Team Canada and Team USA generated the biggest TV audience in Canadian history, and, when Canada won in overtime, created a moment of coast-to-coast-to-coast celebration. The stories generated by hockey, fables of figures larger and stronger and swifter than life, are central to Canada.

And the Montréal Canadiens are central to Montréal. As I said, the 1955 Richard Riot is frequently considered a crucial moment in the history of the city and of the province of Québec. The reason why it could be so important, the reason why the riot took place at all, was because the Canadiens and Maurice Richard were viewed both inside and outside Québec as symbols, or heroic representatives, of the French Canadian people (this being before the popularization of the word ‘Québécois’). The team was founded as a team for Montréal’s French hockey fans; the name ‘Canadiens’ refers to an old usage of the word that specifically refers to French Canadiens. Dider Pitre, Jean Baptiste “Jack” Laviolette, and Edouard “Newsy” Lalonde were the first talented players to be nicknamed “the Flying Frenchmen,” unknowingly beginning a lineage that would extend through players like Howie Morenz, Richard, Béliveau, and Lafleur. For much of that time, Francophones were socially and economically discriminated against; the Canadiens were national symbols, speaking in a particular way to Francophone fans.

It therefore seems a paradox that the biggest stars, people like Richard and Béliveau, are also celebrated for something in their nature fundamentally apolitical (Béliveau was twice asked to be Canada’s Governor-General, the Queen’s representative in Canada, and twice refused in order to spend more time with his family). I think that as legends they are bigger than the historical circumstances that are inherent in any political position. A legend is bigger than any single reading of its story. A legend may inspire to action and so drive political change. But a legend, insofar as it is a legend, speaks beyond time and place.

My background is entirely Anglophone, and I’ve been a Canadiens fan as long as I can remember. In this I am following in a family tradition. The first man to have his number retired by the Canadiens, Howie Morenz, died in hospital following an on-ice injury in 1937; he lay in state at centre ice of the old Montréal Forum, and my father’s mother and mother’s father were both among the thousands of Montrealers who attended. My grandfather, a tremendous fan of Morenz, waited in line for hours to pass by Morenz’ casket, and I note this because my grandfather had a wooden leg. He’d lost his leg years earlier playing hockey, when a deep skate cut grew infected, and those hours he waited he was on crutches; but it was that important to him to pay his respects.

My background is entirely Anglophone, and I’ve been a Canadiens fan as long as I can remember. In this I am following in a family tradition. The first man to have his number retired by the Canadiens, Howie Morenz, died in hospital following an on-ice injury in 1937; he lay in state at centre ice of the old Montréal Forum, and my father’s mother and mother’s father were both among the thousands of Montrealers who attended. My grandfather, a tremendous fan of Morenz, waited in line for hours to pass by Morenz’ casket, and I note this because my grandfather had a wooden leg. He’d lost his leg years earlier playing hockey, when a deep skate cut grew infected, and those hours he waited he was on crutches; but it was that important to him to pay his respects.

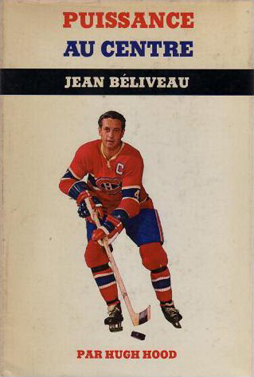

I remember, when I was a young child in my grandfather’s home, reading a small black paperback book published in late 1971 that told the story of that year’s NHL playoffs. They’d been Béliveau’s last, ending with an improbable Stanley Cup win for the Montréal Canadiens led by the retiring captain and by rookie goaltender Ken Dryden, who had played all of six regular-season games. I remember finding the book’s ominous conclusion funny. I no longer have the text to hand, but it read something like: ‘The future for the Cup-winning Canadiens is uncertain, though. The great Béliveau is retiring, and who will replace him? It’s a faint hope that newly-drafted forward Guy Lafleur will become a figure of his stature.’ And this was funny to me because by the time I read those words Guy Lafleur had already become Guy Lafleur, the Flower, one of the greatest players in the league: one of the heroic figures in blue, white, and red that I could watch on TV or read of in the comics (see image at left).

If I am writing so much about my own experience of these stories, it is in an attempt to explain how these legends affected and shaped me. As things I learned from my family, things that I experienced with my family, the lineage of the Canadiens helped shape my own sense of a connectedness to the past. They shaped my sense of myself as a Montrealer. And the values of the stories of these men helped shape my own sense of what is right. In thinking and writing of Béliveau I think and write of a man who defined my concept of the noble, not from any personal knowledge I had of him but through the stories I was told: a man who was worth aspiring to for his ability to say the right thing to the right person at the right time to inspire them to be better. I find at moments I have a tendency, much as some ask themselves ‘What would Jesus do?’, to ask myself ‘What would Jean Béliveau do?’ Again, I never met the man and I have no actual sense of him from direct experience. But the idea of him, as shaped by the stories I have read and been told, has created a legendary figure for me from which I can learn to be better.

Legends are simple things, and mortal life complex, made up of contradictions and exceptions and contexts. But a mortal becomes a legend by making life simple. And the legend then gains a complexity as it lives on: as it develops history as a legend, as it is retold and shaped for new circumstances. As it speaks to a community, and as it speaks to each individual who reads or hears it, and as new meanings and purposes for it are found. We think, and we are not wrong, that a story is for each of us alone, and that our individual reactions, in our own souls, make a story ours. But that same act, that same kind of reaction, takes place within each person to whom the story speaks; a different reaction in each case, a different intuitive response, a different extraction of meaning, but the same reaction in its general nature. It is an acknowledgement that the story, the legend, has said something that needs to be said.

Legends are simple things, and mortal life complex, made up of contradictions and exceptions and contexts. But a mortal becomes a legend by making life simple. And the legend then gains a complexity as it lives on: as it develops history as a legend, as it is retold and shaped for new circumstances. As it speaks to a community, and as it speaks to each individual who reads or hears it, and as new meanings and purposes for it are found. We think, and we are not wrong, that a story is for each of us alone, and that our individual reactions, in our own souls, make a story ours. But that same act, that same kind of reaction, takes place within each person to whom the story speaks; a different reaction in each case, a different intuitive response, a different extraction of meaning, but the same reaction in its general nature. It is an acknowledgement that the story, the legend, has said something that needs to be said.

I went to Béliveau’s lying-in-state at the Bell Centre, the downtown arena where the Canadiens now play. It was the second day of the visitation, and I arrived a little after four in the afternoon; I was in line about half an hour. Behind me were two guys talking about their season in a seniors’ hockey league, and discussing Béliveau’s career with a stranger behind them. In front of me were a father and a son maybe eight or ten years old, the father pointing out to his boy TV screens showing tribute videos and Béliveau’s career highlights.

Inside the bowl of the arena light and shadow had been carefully shaped. The vast space of the rink was left dark except where a lighted aisle led to Béliveau’s casket; and except for two spotlights. One shone in the rafters, picking out the banner commemorating Béliveau’s number 4. The other shone down from above in a tight beam, picking out the seat behind the Canadiens’ bench where Béliveau sat to watch each game. The light was visible in the shadows of the arena, a clear silver shaft from heaven. The lack of definition in the otherwise-dark space evoked the sense of a cathedral, a kind of sacred abyss, leading all eyes to the casket where Béliveau’s family greeted mourners. (Béliveau’s wife Elise shook the hands of every person who came to pay their respects over the course of two days.)

Above the closed casket were two huge banners with pictures of Béliveau. On the left as you approached was a colour picture of Béliveau as an older man, in a Canadiens jersey and holding a torch as part of a team ceremony. On the right was a black-and-white picture of Béliveau in his prime as a hockey player, skating forward. Between them was a banner with Béliveau’s number and ‘1951-1971,’ commemorating his years with the Canadiens. I felt the appearance was striking in the way it told a story: starting with Béliveau as retired eminence, with the sharpness and bright colour of recent recollection; moving then left to right backward through his career, to the black-and-white memory of his glory years, reaching back into dreams.

Above the closed casket were two huge banners with pictures of Béliveau. On the left as you approached was a colour picture of Béliveau as an older man, in a Canadiens jersey and holding a torch as part of a team ceremony. On the right was a black-and-white picture of Béliveau in his prime as a hockey player, skating forward. Between them was a banner with Béliveau’s number and ‘1951-1971,’ commemorating his years with the Canadiens. I felt the appearance was striking in the way it told a story: starting with Béliveau as retired eminence, with the sharpness and bright colour of recent recollection; moving then left to right backward through his career, to the black-and-white memory of his glory years, reaching back into dreams.

And, as you approached, step by step along the red carpet laid across the boards set over the ice, the banners seemed to rise above you, like towers that became grander the closer you drew, as though partaking of the nature of a legend: to be, always, larger than life.

We write here — I write here — about stories, and about heroes. And usually these things are what we agree to call fictions. But fiction and truth have a tendency to meet in the individual mind. There, true things become legend; the recounting of a true event, shorn of irrelevant details and focussing on what is most important, becomes flattened and so more profound. What I am trying to say is that we move in a world filled with heroes and with myths. The stories we tell are shaped by the stories we’ve been told, the stories which have shaped us. Some are clearly fictions. Some are recorded as history. But, without wanting to equate those two things, there is a meaning we ascribe to stories which goes beyond either history or fiction as though, subjectively, to incorporate both: and that is when they become legend.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.