Fiction Review: The Book of the Ler by M. A. Foster

A Review by D. K. Latta

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

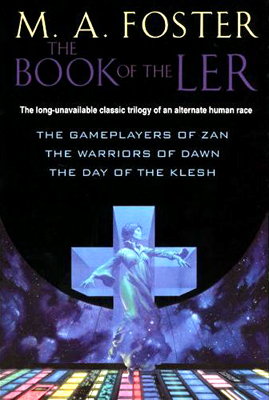

The Book of the Ler

M. A. Foster

DAW (928 pages, October 2006, $15.00)

The Book of the Ler collects three out-of-print novels by M. A. Foster. A trilogy, of sorts, though thousands of years elapse between them.

In The Gameplayers of Zan (chronologically the earliest story, though it was published second) human civilization has fused into a single Dystopian society which shares Earth with the Ler, a genetically engineered subspecies of humanity who live rustically on a reserve. The novel offers a chance to explore this “alien” culture and their biological and societal differences from humans. It’s also a thriller, with shadings of John le Carré — or even Kafka — as characters slowly begin to perceive that a massive and mysterious conspiracy is afoot. Caught up in a grand design, a barely perceived pattern, you become genuinely intrigued to see how it all plays out.

There’s a sense that Foster was torn between writing an entertaining thriller on one hand and a highbrow treatise on existence on the other. The world-building does threaten to go overboard whenever characters launch into lengthy expository monologues explaining Ler customs and rituals. But if Foster sometimes falls into one of the worst vices of SF — belaboring the minutiae and technicalities — his careful development of the characters leavens that. And this lack of a consistent tone is ultimately what makes the story so richly layered, and by the end you are thoroughly involved with the protagonists and situation.

If Gameplayers is an Orwellian political thriller, The Warriors of Dawn is space opera — the main character is even named Han, although it was published before Star Wars. Centuries after the first novel, humans and Ler have colonized the stars. Han and a Ler woman are sent to investigate rumours of a “lost tribe” of Ler who are marauding through a remote sector of space. It starts out a little faster than Gameplayers, with the dangers and mysteries easier to quantify, and some clever “cliffhangers” to end chapters. Long conversations and explanations about the various cultures arise once again, now expanded to include this “lost-tribe” offshoot. But even as the conflicting impulses — highbrow and lowbrow — reassert themselves, the developing relationship between Han and the Ler woman gives Warriors a compelling emotional foundation that shores up both the adventure and the abstract ruminations.

The Day of the Klesh leaps forward another thousand years. An expedition of humans, Ler, and a third, alien race journey to a remote and savage world, where the human population has evolved into a series of segregated cultures and life-forms. Of course, the mission goes wrong, and the travelers end up crashing on the planet. One can initially liken it to early Heinlein, in that the chief protagonist of the story is a naïve young man on his first space expedition. Klesh is the shortest book in the series. . .and ultimately the least compelling. They crash, they encounter the strange inhabitants, but we aren’t quite sure what we’re waiting for other than the general idea of “will they survive”? By the time a mystery asserts itself, it’s too late to fully engage our interest.

Despite shifting locales, time periods, and focus (the Ler aren’t always the most important aspect), Foster employs recurring themes of cultural and genetic evolution and manipulation. The Ler themselves are the product of man’s attempt to create a separate human race; and everyone is either evolving, devolving or stagnating. Conspiracies abound on massive scales, and an underlying pattern to existence is presupposed, a fabric that can be manipulated if you find the correct threads. There is a grandness to this trilogy-that-is-barely-a-trilogy, and a nostalgic 1970s vibe at work — characters reference I Ching and Tarot cards, and the sexual lifecycle of the Ler features a phase of promiscuous free love. Admittedly, plot points can hinge on illogical abstractions and metaphysical concepts, sometimes coming out of nowhere as a deus ex machina. This makes the books read like fantasies as much as science fiction.

Foster wrote a handful of books between the mid-’70s and mid-’80s, but then seems to have done little fiction writing since. Now that this magnum opus is back in print and being advertised as a “long-unavailable classic,” is it worthy of such a label? Taken together, these novels span nine hundred pages and several millennia, and Foster’s style is often as captivating as the themes themselves. Each story is at once convoluted and poetic, dense yet eminently readable. The imagery is rich, the characters generally effective. It flows. The shift between highbrow and lowbrow, the tension between bizarrely metaphysical imponderables leading to B-movie revelations, invites rereading.

An undiscovered classic? Just maybe.