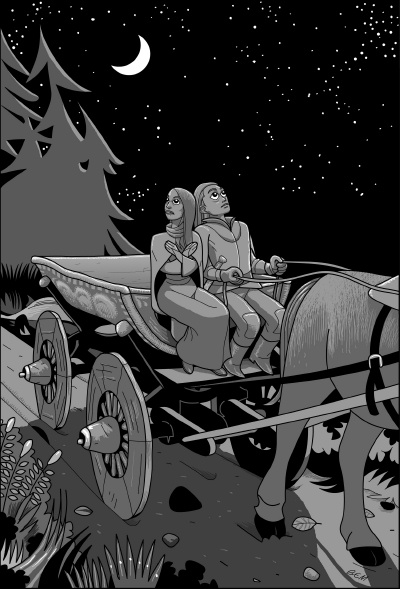

Fiction Excerpt: “The Carrion Call”

By Paul Finch

Illustrated by Bernie Mireault

from Black Gate 8, copyright © 2005 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

It was late autumn and the weather had turned bitter, when King Athelstan and his army arrived outside Earl Ethelwulf’s longhall.

It was late autumn and the weather had turned bitter, when King Athelstan and his army arrived outside Earl Ethelwulf’s longhall.

Ethelwulf of Urs, a veteran of many wars and a winner of renown during Edward the Elder’s hard campaigns at Tempsford and Derby, received his overlord informally, clad in a baggy tunic of old burel, and leather cross-strapped trousers still muddy from the hunt.

“Welcome my liege,” he laughed, coming out from his gatehouse and bowing. “I trust the fyrd is in good heart?”

“I hope to find that out myself,” said the king. “The invaders have crossed the River Don. We plan to intercept them at Weondun… catch them as they ford the Brunanburh.”

“A good plan, sire,” the earl replied. “With an army the size of theirs, they won’t expect to be attacked.”

Eadric watched from the outer stockade, as the king’s host deployed for encampment in the southern meadow. He didn’t think he’d ever seen so many men — perhaps fifteen thousand in total. For all their numbers, however, Eadric couldn’t help wondering if they’d be a match for the dark tide of destruction sweeping westwards across Mercia. Aside from mounted companies wearing heavy hauberks and full helmets, with axes and shields on their backs, and double-edged broadswords at their waists — the royal housecarls, only about two thousand at most — the vast bulk of the king’s force was a motley band. Several thousand were thegns — clad also in shirts of rings and gilded helms, riding in support of the earldormen, but most of the rest were peasant stock, harnessed with coats of leather and improvised shields. All were spattered with mud from days of forced marching, and though some carried proper weapons like spears and hunting-bows, many were equipped with little more than farming implements — knives, pitchforks, mallets. Was it possible, Eadric wondered, that these relative few could even stand their ground against the forces of Olaf Guthfrithsson, King of the Norse-Irish and chieftain-in-chief of the dread Clan Strykar?

The truth was that Eadric, who was still only twelve, knew little about the Vikings other than what he’d overheard the hearth-men say… but this was fearsome enough. It had been a dark day for Ireland, they’d whispered, when Guthfrithsson and his father took their fleets over the broad green seas to Dublin. No evil the ancient Geadhil had ever inflicted on each other could compare with the ferocious conquests of those two warlords. They’d plundered the whole of Munster, Leinster and Ossory, ravaged and destroyed the churches and sanctuaries, burned the great libraries to ash. They’d killed Ireland’s kings and champions, and enslaved their dark haired-women, placing all in nunneries of sin. The emerald island itself, they’d carved into choice steaks and given over as sword-land to their fanatical followers. And now they were here, in England… at least forty thousand strong. That wasn’t all, however. Other hosts of Northmen had joined them… vengeful Danes driven out of York by Athelstan, crews of adventuring Finns and Geats, not to mention Laps, Orkneymen, Icelanders, even Rus and Varangians disaffected from their masters in the east. To make things worse, the pagan kings Owain of Strathclyde and Constantine of Alba had also seized the day, adding a further twenty-thousand Celts to the foe, war-bands from every hilltop stronghold, plus hordes of wild Picts from the high country and the Small Isles to the west… terrifying creatures, clad only in skins and daubings of fiendish blue woad.

A prodigious army now marched inland from the River Humber. They’d been moored there four days before their vast numbers had fully disembarked. There might be sixty or seventy thousand of them… a multitude so immense that, marching fifteen abreast, they were twenty miles deep. Yet even as they came, slashing and burning crops, looting villages, more traitors flocked to their heathen banners… men of the Welsh and the West Britons, even levies of the north Saxons, sent out by the Christians of Northumbria as tribute to buy off slaughter. Eadric envisaged a moving forest of pikes and axes, every road a dark and dusty mass of helms and shields, the sacred sod of England shaking to the tramp of iron-shod feet. The thought alone filled him with such horror that when Eadith, his younger sister, came and placed a hand on his shoulder, he jumped violently.

“God’s blood!” he shouted, almost falling from the gantry.

Eadith flushed under her flaxen locks. “Don’t swear… mother wouldn’t have approved.”

Eadric nodded sullenly. Normally he might respond stingingly to any reprimand from his only sibling, but memories of their gentle, now deceased mother always mellowed him.

“What do you want?” he asked.

“Father said you should come in now and ready yourself for the feast.”

Eadric nodded. “I will. Shortly.”

She moved off. Eadric glanced back at the king’s army. Their tents were now appearing, their many standards starting to billow in the breeze. The air was alive with the sounds of animals, the shouts of men, the clink of hammers on anvils. Fifteen thousand wasn’t a small number, the boy reasoned. He looked over his father’s homestead of Godhalling… a long, slope-roofed building, set behind earthworks, stockades and a maze of animal pens. Not a great deal to lose, even with its numerous hides of plough-land, its fishponds and deer-chase. But it was all they had, and yet the following morning, with the first cock-crow it would be left undefended as Earl Ethelwulf and his hearth-troop joined the king.

Eadric tried to contain his fear, but he couldn’t. Shuddering again, he hurried off to get ready.

There dwelt the troll-kind, in the fastness of the mountain. Gigantic, brainless brutes, with a wild craving for human flesh. Only Alsvidh and Arvak’s morning glory could sear them back to the stone of their birth.

Yggdrasil / Jormungand

Inside, Earl Ethelwulf’s longhall was a huge, airy chamber, built from rock at its four corners, but otherwise timbered and vaulted along its ceiling with a hundred pine trunks. Six great crossbeams were decked with linden shields and ash spears, while every wall was adorned with splendid tapestries, depicting gryphons and eagles, longships, angels and scenes from the Passion. There were heroes, hermits and martyrs, even Edmund of the East Angles shot full of arrows and enduring the agonies of the Danish blood-sacrifice.

At one end of the hall there was an open hearth now stacked with holly logs and host to a roaring winter fire, at the other a pair of solid oaken doors, studded with brass nails. The floors were strewn with dried grasses, with a single long-table running down the middle, and benches and trestles ranged around the walls. Though stolidly Christian, Earl Ethelwulf had never forgotten the pagan heritage of his Anglo-Saxon ancestors. Every item of woodwork in the hall was thus intricately carved with foliage or elves, with dragons’ heads, toads, the wings of birds and winding serpents. There was a permanent fragrance of fruit and evergreens, while sprigs of parsley and honeysuckle — the herbs of healing — dangled over the fire.

As well as the king, his brother, and their earldormen, the great hall and its outbuildings were already milling with people — visiting tradesmen, the earl’s friends and relatives, their families, and an army of servants, grooms and slaves, not to mention Ethelwulf’s own hearth-troop, but in the old Saxon tradition, every person there, be he never so base, was to be accommodated as guest and friend. Thus, the ale that night flowed rich, the mead endless and sweet. Ethelwulf, seated at the head of his table, with the king to his left and Prince Edmund, the royal brother, to his right, raised his drinking-horn and called toasts in the honor of Christ, the coming of spring and the good health of their guests.

He might have been a lesser landlord, but no one could accuse Earl Ethelwulf of not being generous. The fare he had provided was sumptuous in the extreme. Great trenchers of hot meat and steamed vegetables were brought in, to the accompaniment of cheers and the crashing of knife-hilts on tables. Once the repast was finished, there was juggling and wrestling, then the skalds came forth in their cloaks and shoulder-clasps, armed with harps, and as the company gathered closely about the glowing hearth, they related epic poems and sang the songs of the Homelands.

Throughout it all, Eadric watched the royal guests, fascinated. Physically, the king and his brother were very similar… though Athelstan had the look of greater virility. In height and breadth, he was the equivalent of any man there, his arms and neck thick with warrior’s muscle. He gave off an aura of strength that was almost leonine, his cat-green eyes, shaggy blonde mane and rich, curling beard only adding to the effect. It was easy to imagine, the boy thought, that this was Athelstan, the legendary ‘Hawk’ or ‘Thunderbolt’, the scourge of the heathens, the one who had bent the Danelaw and all the kings of Britain to his will, and even in the wilds of Wales, had made the fierce Cymri acknowledge him as Mechtteyrn, or supreme overlord. The very sight of him warmed Eadric inside, but when the sovereign actually spoke, there was an angry defiance in his words, which infected everyone there.

“There’s a gnarled oak in the fruit-gardens of York Minster,” the king said. The great chamber fell silent. “It’s a thousand years old. Struck by lightning over and over, yet still it thrives, spreading its black boughs further each season. The Viking Anlaf Sihtricsson, whose entire army you may remember… I slew, has vowed that when he and I meet again, he will nail my heart and lungs to that tree.”

The silence lingered, but the king only smiled. “In return, I have vowed that I will have him baptised, forgive him his harsh words… then hang him on the highest gibbet in Christendom.”

There were roars of approving laughter. Eadric was amazed. The king seemed fearless in the face of this terrible threat to his realm. Surely, of all the men there, he was the one who stood to lose most? Doubtless he had heard about the hideous tortures inflicted by the Norse on those noblemen they’d captured: the creation of heimnars…prisoners whose limbs were hacked off and whose stumps cauterized, so they would survive the blood-loss and then face a living-death as grim mockeries of humanity; the ghastly ‘Walk’, yet another sacrifice, in which a captive was forced to endure an incision in his lower belly, from which an intestine would be drawn and fastened to a monolith… he would then be made to circle that monolith again and again until the entirety of his guts were wrapped around it…

That thought alone was so horrible that Eadric wanted to be sick, though even he wasn’t quite so frightened as his sister. Towards the end of the feast, she came to him. “Eadric,” she said, “what if father doesn’t come back?”

“He will.”

“But I’ve just heard some of the servants making plans to leave. They say a battle’s coming which the king can’t win.”

Her brother scoffed. “Servants… what do they know?”

“They say the Vikings are too many.”

“People said that when Alfred faced the Danes at Ethandun?”

“I wish King Alfred was alive now.”

Eadric tried to comfort her. “King Athelstan is better… because in his person Wessex and Mercia are united. We have more men than we would have if it was just his grandfather.”

Eadith didn’t look any happier. “We still haven’t enough.”

“Battles aren’t all about numbers, Little Rabbit,” he told her, wishing that he himself believed this. “They involve skill, tactics…”

“But even if the king wins, father might still be killed?”

Again, her brother waved this possibility aside. “Has he ever failed to return from campaign? Has he ever even been wounded? Look at the thegns he’ll have around him.” He pointed to his father’s own hearth-troop; to a man brooding, dark-eyed warriors who wore their flaxen hair long, their beards thick, and their arms and hands adorned with rings and bangles… the honors of war. “There’s Wulfgar, Nors, Ethric. These are trained champions. They’ll defend him to the last.”

“I hope so,” said Eadith, who only knew the household men as gregarious jokesters, who would tease her about her little buds, and bring presents back for her when they traveled.

Eadric didn’t mention what he’d overheard about the fate of several of the war-bands who had so far opposed Guthfrithsson. Many of those captured had been flayed or crucified, hung by their own bowels, stuffed with tarred straw and burned from the inside out. Nightmarish images assailed the boy, but in the face of his sister, he kept a square jaw. “Go to bed now and sleep,” he said. “You’re on milking-duty early tomorrow.”

Eadith looked surprised. “But father and the king are leaving tomor…”

“It’s just another day for you, Little Rabbit. Go and sleep. You’ll need it.”

The girl turned and went, and only when she had gone, could Eadric give full vent to his own fears, gnawing on his knuckles like a ceorl facing the ordeal.

They feared the berserkergang most. Our carls stood foursquare in battle, with each slain foe an offering to the Allfather. But the berserkergang ran crazed, with a wolf’s joy in killing. They dressed in the wolf’s fur, howled at the wolf’s moon. At times, they became as the wolf himself, ravaging all with tooth and forepaw…

Ynglingasaga

When Eadric woke, it was still very early and dark outside. The air in his small bed-chamber was freezing cold. Shivering, the boy turned on his cot, pulled the blankets to his chin.

He lay still for a moment, wondering what had woken him. Then he realized… torches glinted beyond the shuttered casement, there was the low rumble of hooves and tramping feet, the jingle of harness, the squeak of ox-carts laden with munitions and supplies. Men’s voices could be heard, though there was no shouting, no laughter… only mutters and mumbles.

The door to the room opened, and a faint light fell across the bed. Eadric glanced up as his father came in. Earl Ethelwulf was already girt-up for battle, clad in stout leather, but wearing as well his “elf-mail”… a fitted coat of steel rings, with a layer of gleaming scales on top of them. When polished it shone like silver, and according to household myth, could not be pierced by blade or point. Whenever Eadric questioned his father on this, the earl would simply laugh and speak of it as a fine piece of plunder, rent from the back of a slaughtered Dane at Tempsford. In addition, the great warrior now wore gauntlets of chain, and under one arm carried his battle-helm, distinctive for its molded cheek and nose-guards. His mighty broadsword, with its carved handle of gemstone and walrus ivory, was belted to his hip.

“Perilous times, lad,” said the earl.

“Yes, father,” replied the boy, sitting up.

“It feels like the whole army of Hell is loose in the land.”

“I know that.”

“Well all need to be brave.”

Eadric nodded. “The king sets a fine example.”

“He does indeed, lad.” The earl paused for a moment. “And you must copy him.”

“Me, father?”

“You’re not a man yet, Eadric. But you may need to act like one very soon.”

Eadric nodded.

“You realize what I’m saying?”

“That you might die.”

Ethelwulf sat down at the end of the bed. His voice softened. “There is more.”

Eadric listened in what he hoped was manly silence.

“This Viking army is like no other,” the earl said. “They’re bent on rape and massacre of course, as always, but Olaf Guthfrithsson has years of English victories to make score with. If he kills me or even kills the king and his brother, it won’t stop there. The brutal conquest will go on and on, ‘til there isn’t a church left standing, not an English earl left in his seat.”

Ethelwulf paused for breath. “In short, lad, they aim to wipe Cerdic’s people from the map, to erase the memory of Christian England. Our land will survive, but only as part of the heathen Nordic world.”

Still, Eadric listened in silence, though he had to swallow his fear in a bitter lump. It was an apocalyptic vision his father was invoking. What would happen to those who didn’t or couldn’t fight? Did this mean that all their lives might be over?

“I said nothing of this to you last night, lad, because I felt you needed at least one good sleep before the army moved out,” Ethelwulf added.

“Can the king not win?” the boy asked tremulously.

“The odds are fearful, but we must make the stand anyway.”

“Will you stand to the last?”

The earl half-smiled. “It may be hard not to… though I’ve never been one for foolish gestures. Alfred survived the fight at Chippenham to live wild in the marshes of Athelney, until such time as he could gather a new army and win back his throne. Of course, the Norse will remember that too. They’ll go all out to butcher us.”

Eadric nodded. This made sense, but it was encouraging to remember the victories of King Alfred, also secured against demonic opposition.

“Whatever happens though, Eadric,” the earl added, “and it’ll happen soon enough because Weondun is only a day’s march from here, you and your sister must survive.” He paused again, then took the boy’s wrist in a no-nonsense grip. “Godhalling is our home. Everything we have of value is here… our wealth is sunk into the very land. But if the Vikings triumph, you must flee this place. Take nothing with you, neither good nor chattel. Just your sister. Go straight south. Head for Exhall, link up with your cousin Edgar, or your Uncle Raedgald at Malmesbury.”

Eadric was surprised. “Are they not coming here?”

“I’m afraid not.” Ethelwulf shook his head slowly. “Not all the earldormen of Wessex have flocked to Athelstan’s banner. Some of them despise him for his Mercian blood.”

“But his father was Wessex…”

The earl gave another smile, this one cynical. “Any tainting of the royal line is deemed filthy by some. Those fools! How will they fare if the king falls?”

“The king won’t fall, father,” said the boy, as boldly as he could.

Ethelwulf nodded. “That’s very possible. But even if he doesn’t, there’s a chance I might not return. Forget the glory. War is Hell, Eadric… an unfair lottery which can snuff a man out at a moment’s notice. Still… if I am taken, it won’t be entirely bad news for you. As eldest-born, you’ll be sole heir to the land and the title, though at first you may need to scrimp and scratch to keep it. In that circumstance, I ask only one favor. Find my body and bury it the Christian way.”

“Yes, father.”

Earl Ethelwulf looked his son in the eye. “This is not as simple as it sounds. Our family has long been followers of Christ, but it’ll all come to nothing for me if I am dispatched with men’s blood on my sword, then burned on a pagan pyre. I beg you, Eadric… find my bones and lay them to rest in the sight of God.”

The boy nodded, quite determined that this was the least he would do. “I will.”

“You promise, lad?”

“I promise, father.”

And at that, Earl Ethelwulf stood. A gauntleted hand stole to the hilt of his broadsword. “Wish me luck then, eh? I go to defy the Devil.”

Athelstan, king, lord of earls, ring-giver to men, and his brother also, the atheling Edmund, lifelong glory struck in battle with sword’s edge at Brunanburh. Edward’s sons broke the shield-wall, hewing linden-wood with their hammered weapons, for it came natural to men of their lineage to defend their land, their hoard and their home against every foe. The hated ones were crushed, people of the Scots, men of the ships, all met a dreadful fate. The field was slick with men’s blood, and by the sinking of the sun, God’s bright candle, many a man lay transfixed by spears, countless northern warriors were dead under their shields. The West Saxons, in mounted companies, went forth all the day long on the enemy’s tracks, hewing the fleeing forces from behind with blades new-whetted on grindstones. No stroke did the Mercians refuse to pay to any who, with Olaf, had invaded this land from the sea. Five enemy kings lay dead on the field, slain by the sword, and also seven of Olaf’s earls, and numberless Vikings and Scots. The Norse tyrant was put to desperate flight…

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, AD 937

The first intimation that something wonderful had happened was when beacon-fires were spotted on the eastern hills. A day later, a rider came through shouting the joyous message… that the king had destroyed the enemy force in a single battle on the River Brunanburh.

With tremors of suppressed excitement, the household at Godhalling went about their daily duties as if nothing had happened, ploughing and sewing, gathering nuts and firewood for the winter store, fattening the pigs, collecting tithes from the sokemen, sacking up goods for market. There was no break in the routine. It wouldn’t do to get too ecstatic yet, when the fine details of the engagement might still spell disaster.

The following day, a small group of men arrived who had clearly been at the battle. They rode proudly, their bolsters crammed with booty, but for all that were a tired, bedraggled bunch, stained with mud up to their cross-garters, visibly cut and bruised. Eadric and Cuthred, his father’s senior steward, went out to meet them, ordering the servants to bring feed for the horses and jugs of fresh ale for the men. The leader of the newcomers, a hoary old thegn, clambered wearily down and refreshed himself. Eadric and the rest of the household waited in expectant silence. The thegn, who bore an ugly slash under his left eye, and whose cheek was still streaked with blood, drank enough for three men before he finished and wiped his mouth.

“What is this place?” he then asked.

“Godhalling,” Eadric replied. “My father is Earl Ethelwulf.”

The visitor glanced around, taking in the longhall and its stout outer defences. “You sent men with the king?”

“Thirty. My father led them.”

The man nodded. “Well… it was a magnificent fight, but a hard one.”

“Do you know anything about what happened to Earl Ethelwulf?”

The man shook his head. “I can’t tell you. We massacred the invaders, but half our own army died in the process.”

“How did the king manage it?” Cuthred wondered. “When he was so outnumbered?”

The man smiled. “A clever strategy. The bulk of us met the pagans straight on in a spearhead formation. They had ranks of berserkir at the front, but we were so tight we breached them straight away. The rest of them closed in around us… Scots to the left, Norse to the right. Then the king came. He attacked them on horseback. He’d kept a thousand of his best back from the fray, and circled round. When they weren’t looking, he charged. They just panicked. Their lines fell apart and we were in. Like I say, it was a bloody slaughter – maybe thirty-thousand of them fell, but it went on for the whole day and we lost a good host of our own men too.”

“And you know nothing of the Godhalling contingent?” Cuthred asked again.

“No.” The man then added: “It got wild towards the end. Like a free-for-all. I’ve the Devil’s own job accounting for most of my band. These six you see here are all that remain from eighteen. I hope some of the others made it through, but I wouldn’t put money on it.”

Over the following hours, other stragglers came by with similar tales to tell. One or two were critically injured, and being dragged on litters, while others had done well from the clash, wearing purloined Norse and Celtic jewellery, leading strings of riderless horses. None of them could throw light on the whereabouts of Earl Ethelwulf, even those who knew him.

“I think he and his men were in the thick of it,” one man said, “but then I lost sight of them.”

“They were right there in the front line,” another remarked, “but it was such an orgy of slaying that anything could have happened.”

When two more days passed, and no further news was received, the household grew uneasy; one or two menials vanished overnight, taking their belongings with them. Cuthred counselled patience, advising that everyone stay calm and continue with their scheduled duties. Eadric, however, was uncomfortable with this. He felt certain that by now, his father, or some member of his father’s war-band, would have sought to send a message back, especially as the River Brunanburh was only a day’s march away. At length, with increasing concern, he went to see the monk Osbert in his stone cell.

Osbert, a pinched, balding man, who always looked swamped in his black Benedictine habit, was busy at his illumination. He barely looked up when the boy entered.

“Some of the servants have run away,” Eadric said.

The monk nodded. “It’s only to be expected.”

“They’re worried,” the boy added. “They don’t want to spend the winter under the protection of a twelve-year-old.”

The cleric remained unruffled. “With the Vikings defeated, the roads will be safer. The weather hasn’t yet broken. It’s a good time for them to travel.”

Another moment passed, the candle flickering over the monk’s easel.

“Is that all you can say?” Eadric eventually asked.

“My boy, servants are promoted peasants. They are always the first to run in times of crisis. It’s when the slaves desert that you have a problem. If a man risks the death penalty to avoid your command, then you know trouble is brewing.”

“But how can we manage the estate?”

Osbert seemed indifferent. “The main danger was the heathen horde. It has been averted.”

“But what if my father was killed?”

“Everybody dies, Eadric. It’s only a matter of when.”

The boy found it hard to believe that he was having such a conversation. “Mustn’t we go and find him?”

“Why? We can scarcely resurrect him.”

“We must recover his body. Bury him.”

For the first time, the monk looked round, a single eyebrow raised. “Have you ever seen a battlefield, young man? You don’t want to.”

“But we can’t just leave him there.”

“On the contrary, we can.” The monk went back to his array of inks. “If your father was killed, he’s nothing more now than a husk. His spirit will have gone on.”

“With all respect, how do we know that?”

At last the monk became irritable. “For Heaven’s sake… it was a battle! He’ll have been shriven and heard Mass first. They all will. You must accept this, Eadric… war and its risks are the down-side of your father’s and your privileged position. Now give me peace. I am working.”

After that, Eadric went to look for his sister. He eventually found her beyond the outer stockade, in the southern coppice. She was kneeling by the ancient Celtic cross, where she had taken to saying her prayers. It was a scenic glade, which in spring was flooded with golden daffodils, and in summer with a brilliant profusion of violets. Now, in late autumn, it was bleak and windswept, strewn with dead leaves and damp, broken twigs. Eadith was there all the same, kneeling beside the moss-covered monument. She had been crying.

“I’m going to find father tomorrow,” Eadric said.

Eadith sat back on her heels. “How will you know where he is?”

“The army’s trail should be easy to follow.”

“Won’t it be dangerous?”

He shrugged.

Eadith considered for a moment. “Who will you take with you?”

Eadric gave a wry smile. “I doubt anyone will come. Both Cuthred and Brother Osbert advise that my duty is here.”

“Shall I come?” she asked.

For a moment he looked unsure, then: “Common sense tells me no, but I promised father that I would keep an eye on you.”

Eadith thought about this. She didn’t like the idea, but already distraught at having lost touch with her father, she didn’t want to lose it with her brother as well. “I suppose it will be easier searching with two,” she said.

Eadric nodded, then set off back. “We’ll leave tomorrow, first thing. I’ll take one of the trade-carts. We might need to bring back a body.”

“Yes,” said Eadith quietly. “I’ll pack some victuals.”