The Hardy Boys Meet M.R. James: The Supernatural Mysteries of John Bellairs

In the world of publishing today, books written for children and young adults are the tails that are increasingly wagging the dog, especially when those books also fall into the horror, fantasy, or science fiction categories. Many mainstream or “literary” authors would probably sell their souls to Voldemort for the kind of success that J.K. Rowling achieved with her Harry Potter books, though Thomas Pynchon or Phillip Roth pushing Harry from his place atop the bestseller lists would be rather like a Marxist literary critic becoming a judge on Dancing With the Stars. (That’s something I’d like to see, actually.)

In the world of publishing today, books written for children and young adults are the tails that are increasingly wagging the dog, especially when those books also fall into the horror, fantasy, or science fiction categories. Many mainstream or “literary” authors would probably sell their souls to Voldemort for the kind of success that J.K. Rowling achieved with her Harry Potter books, though Thomas Pynchon or Phillip Roth pushing Harry from his place atop the bestseller lists would be rather like a Marxist literary critic becoming a judge on Dancing With the Stars. (That’s something I’d like to see, actually.)

One relatively new aspect in this ascendance of what is called YA (or young adult) fiction is its popularity with older readers. Where in previous years some might be embarassed to be seen reading books written for younger readers, now there is nothing unusual in seeing people with jobs, mortgages, and children of their own eagerly perusing The Hunger Games or Twilight.

And why not? (Well, I could give you a big why not for Twilight, but that’s another matter.) Good writing comes in all sorts of packages, and there are plenty of legitimate pleasures to be had in reading the best YA books.

However, in sorting through the many worthwhile reads available in this era of new-found YA respectability, it is easy to overlook work that was written before the current boom; some fine authors of only twenty or thirty years ago are now unjustly neglected, their reputations eclipsed by those who are fortunate enough to still be alive and producing new work in this YA golden age (a golden age of cultural visibility and publishing advances, if nothing else.)

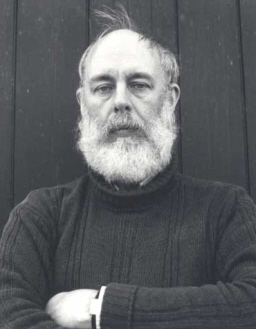

One such writer who perhaps came just a little too early was the once highly popular writer of children’s supernatural mysteries, John Bellairs, who died in 1991.

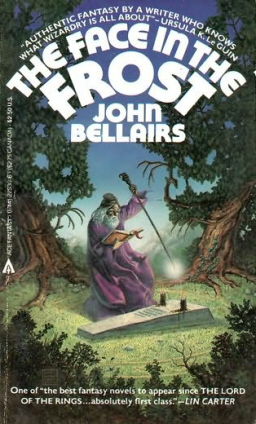

If Bellairs is remembered by fantastic fiction readers at all, it is for his single adult novel, the superb and eccentric fantasy The Face in the Frost, which was published to little notice in 1969. (Though in his 1973 history of the genre, Imaginary Worlds, the ever-perceptive Lin Carter hailed it as “one of the best fantasy novels to appear since The Lord of the Rings.”)

Why was The Face in the Frost Bellairs’ only adult fantasy? Why didn’t he spin it into a fifteen volume franchise, or come up with other fantasy tales aimed at grown-up readers?

Why was The Face in the Frost Bellairs’ only adult fantasy? Why didn’t he spin it into a fifteen volume franchise, or come up with other fantasy tales aimed at grown-up readers?

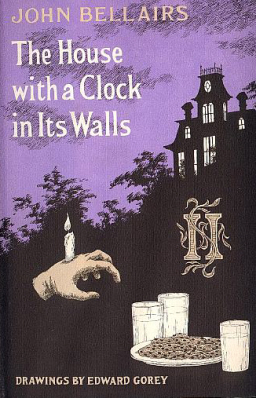

The answer, hard as it may be to believe from our Game of Thrones-dominated vantage point of 2014, is that he tried to and was told by his publisher to forget it; there was not enough of a market for that sort of thing. Instead, he was advised to take the next book that he had written as an adult fantasy, The House With a Clock in Its Walls, and rewrite it as a young adult book.

Bellairs complied, and the novel was published in 1973. It was a substantial commercial and critical success, winning a New York Times Outstanding Book of the Year award, and setting the pattern that Bellairs would follow for the rest of his career. The House With a Clock in Its Walls was the first of fifteen young adult books that Bellairs would write over the remaining eighteen years of his life.

All of Bellairs’ YA books fall into three series featuring three ostensibly different but roughly similar young protagonists: Lewis Barnaveldt (who appeared in three books, starting in 1973 with The House With A Clock in Its Walls), Anthony Monday (the hero of four books, beginning with 1978’s The Treasure of Alpheus Winterborn), and Johnny Dixon (who was featured in eight books, starting in 1983 with The Curse of the Blue Figurine.)

After Bellairs’ death, Brad Strickland completed four more books from outlines and incomplete drafts that the writer had left behind, and has gone on to write nine original novels using the Bellairs characters, the last one appearing in 2008.

The three series are externally all quite similar. They are all set in small towns in New England or the Midwest, and the time is always the late 1940’s or early 1950’s, just when Bellairs himself was the same age as his young protagonists, who are ten to fourteen years old. (Bellairs was born in Michigan in 1938.) The boys are all Catholic (as was Bellairs), and the trappings and rituals of that church make frequent appearances in the novels. (Latin often rears its deformis caput, in dusty documents or on chiseled inscriptions.)

Family circumstances are always complicated or strained — Lewis is an orphan who lives with a bachelor uncle; Anthony has a relatively “normal” family, but in his case that means a father whose compromised health keeps him in the background and a worrying, domineering, money-obsessed mother; Johnny’s mother is dead and his father is fighting in Korea, so the boy lives with his elderly grandparents.

All three boys are intelligent, curious, bookish, and shy, and are of course poor fits at school and in typical social situations with their peers.

All three boys are intelligent, curious, bookish, and shy, and are of course poor fits at school and in typical social situations with their peers.

They all have adult mentors who are closer to them than any friends of their own age, though their solitariness is less a matter of choice than it is the inevitable consequence of awkwardness caused by doing too well with schoolwork combined with an inability to play sports.

Lewis has his Uncle Jonathan and his uncle’s best friend, their next-door neighbor, Mrs. Zimmerman, two friendly adults who turn out to be powerful wizards. Anthony has the local librarian, Miss Eells, who provides him with an after-school job, and more importantly, the uncritical support and warm affection that he rarely gets from his mother. And Johnny has his grandfather’s friend, the eccentric Professor Roderick Childermass, a footloose master of all kinds of arcane lore.

As Bellairs progressed through his three young protagonists, he gradually increased both their age and self-reliance. Lewis is ten, while Anthony and Johnny are fourteen and thirteen respectively, but these differences aside, their characters are quite similar.

Bellairs saved his experimenting for the mentor characters, who show more variation than the boys do themselves. Lewis’ Uncle Jonathan and Mrs. Zimmerman are, notwithstanding their magical power (Uncle Jonathan eclipses the moon one night to provide a bit of amusement for a backyard party), kindly and sympathetic.

Their main distinction is the playful bickering and needling that they constantly engage in, making them a bit of a sorcerous comedy duo. The spinsterish, no-nonsense Miss Eells is almost a normal person, though she’s resourceful enough when it comes to dealing with cryptic clues, cursed magic lamps, and interdimensional portals.

Professor Childermass is perhaps the most successful and fully-realized of the mentors, humorous, hot-tempered, crotchety and cantankerous in a non-threatening way, pleasantly eccentric (he smokes — good heavens! — foul imported Turkish cigarettes, and has a special padded closet in his house where he goes to work off his rages), and is a timely fount of odd and useful information.

The stories typically deal with the incursion of evil spirits (often of deceased wizards or sorcerers) into the mundane world, usually through a gateway opened with some sort of artifact or talisman. (Bellairs acknowledged the master of such tales, the ghost story writer M.R. James, as one of his primary influences.) The boys and their friends then have to find a way to banish the revenants or destroy their influence, before even worse things ensue — frequently the end of the world is the looming consequence should they fail.

The plots of Bellairs’ books can admittedly be somewhat repetitive, but in the best of them the atmosphere and suspense are first-rate and though he wrote the books for younger readers, he didn’t soften the mood of impending doom and oppressive evil that pervades them.

There are scenes of fright and supernatural menace that are strong enough to stand in any adult horror story, and these scenes are all the more effective because the characters that we experience them through are young boys, boys who are facing these horrors hampered by all the natural fears and confusions and insecurities and ignorances of childhood.

Indeed, while Bellairs handles the supernatural devices and conventions with a masterful hand, it is his combination of extraordinary perils with the ordinary terrors of childhood that gives his books an extra power. In The Curse of the Blue Figurine, for example, Johnny Dixon is given a magic ring by a seemingly kindly stranger, who turns out to be the ghost of an evil priest. The boy soon discovers that the ring makes him a slave to the ghost’s will, but the malevolent spirit tells him that if he tries to take it off, he will die.

Indeed, while Bellairs handles the supernatural devices and conventions with a masterful hand, it is his combination of extraordinary perils with the ordinary terrors of childhood that gives his books an extra power. In The Curse of the Blue Figurine, for example, Johnny Dixon is given a magic ring by a seemingly kindly stranger, who turns out to be the ghost of an evil priest. The boy soon discovers that the ring makes him a slave to the ghost’s will, but the malevolent spirit tells him that if he tries to take it off, he will die.

In the face of the ghost’s power and threats, Johnny is utterly helpless. He is convinced that there is no one he can confide in, and that he has to bear his terrible, unbearable secret alone. Bellairs does not flinch from depicting the hopeless anguish and isolation that a child would feel in such a situation. It is strong stuff.

The confusion and loneliness and anxiety of children who are at the mercy of a world filled with inscrutable adults and inexplicable circumstances, a world that can turn cruel and sinister without warning — Bellairs takes these things as givens, and then uses his supernatural props and evil, ghostly incursions to heighten them even further, taking the pain of the everyday social ostracism felt by boys who can’t throw a baseball or win a schoolyard fight and raising the stakes to Doomsday itself by means of dusty grimoires, accursed amulets, and malicious revenants.

Bellair’s books are inventive, enjoyable gothic thrillers, yes — but the fear and menace in them is very real, and not always to be dispelled by the appropriate charm or incantation.

Like all the best YA books, the picture painted in these stories is one of a world that is more complex than a simple happy ending allows; the echoes of evil persist even when the evil itself has been silenced.

One more thing should be mentioned — twelve of Bellairs’ fifteen original YA novels were illustrated by the incomparable master of the visual macabre, Edward Gorey, and rarely have writer and illustrator been better matched.

Most of the books are currently in print, which is a good thing, but the most recent editions (from E-Reads) omit the Gorey illustrations, which is a very, very bad thing.

Happily, fully Gorey-fied copies are easily obtainable used, usually at very low prices. (For paperback editions, that is — the original hardcovers published by the Dial Press, and which feature beautiful wrap-around Gorey covers, are very collectible and can be pricey.)

If you haven’t read The Face in the Frost, you should — that’s all there is to it, and if you’re not familiar with Bellairs’ juvenile work, The House With a Clock in its Walls or The Curse of the Blue Figurine are good places to start.

In his too-short life, John Bellairs produced a body of fine work that deserves to be remembered and revisited, not just by those who shivered to it in middle school, but by everyone of any age who loves the particular chill that only a supernatural brush with the genuinely frightening can bring.

This underappreciated author’s spirit should haunt us for a long, long time.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife.

Thomas, “the echoes of evil persist even when the evil itself has been silenced” is an awesome line.

The House With A Clock In It’s Walls was tremendously popular at the bookstore that employed me back in the day. Bellairs was regarded by local teachers as offering the kind of stories that could pull in reluctant readers and make them pay attention to the page.

Oddly enough my strongest memory of those days involves a customer who would not believe me when I told her Bellairs had written an adult novel called The Face in the Frost. She explained that she was a big fan and would have known about it if he did. Became quite angry with me when I persisted that he had. I backed off.

Wonder if she ever read that book…

[…] The Hardy Boys Meet M.R. James: The Supernatural Mysteries of John Bellairs […]