The Art of Storytelling and The Temple of Elemental Evil

Role-playing games have always interested me because, at heart, they’re about stories. They’re ways to tell stories that you don’t know in advance, ways to bring people together to create something unpredictable but still structured in a narrative form. Now, that said, the question is: how do you go about doing that? If you’re writing a module, an adventure, that referees are going to pick up off a store shelf (or download from a web site), what do you give them to help create that story with their players?

Role-playing games have always interested me because, at heart, they’re about stories. They’re ways to tell stories that you don’t know in advance, ways to bring people together to create something unpredictable but still structured in a narrative form. Now, that said, the question is: how do you go about doing that? If you’re writing a module, an adventure, that referees are going to pick up off a store shelf (or download from a web site), what do you give them to help create that story with their players?

The traditional first edition Dungeons & Dragons answer to this was: you give them a dungeon. You give them a sandbox, an area to explore filled with monsters and treasure, and maybe a few adventure hooks. What will the players do with it? Who knows?

For a long time, probably starting in the mid-80s at about the point where I started seriously playing D&D, this approach was in disrepute. A dungeon with a bunch of monsters isn’t a story, the argument ran. A story should have a structure, and ideally different moods, maybe even different settings. It should end in a different place than it began. You could see this philosophy settle in at TSR with the Dragonlance series of modules, taking firmer hold with second edition D&D.

Nowadays, though, at least a few people are beginning to swing back to the first approach. Structuring stories out ahead of time kills the spontaneity of the game, one might argue. Let the players and referee develop the story at the table, not by going through the motions worked out ahead of time by some designer. Don’t railroad the players; give them the situation, and see what they do on their own. (I’m vastly simplifying all these positions, and only presenting some of the arguments. I think I’m getting at the essence, though.)

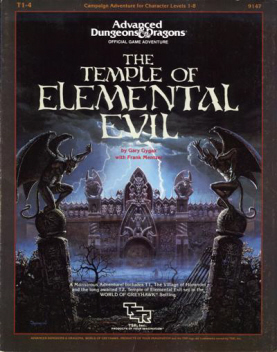

I’ve come around to that last argument. I want to explain why, because I’ve recently wrapped up a First Edition game in which I was fascinated to see a story I never anticipated arise out of a module that features little in the way of pre-structured narrative: The Temple of Elemental Evil by Gary Gygax and Frank Mentzer (TSR, 1985).

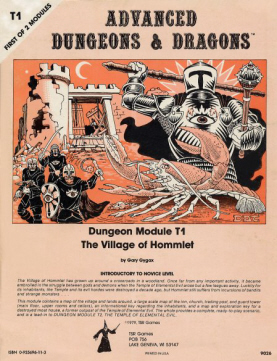

The basic idea of the module goes roughly as follows: The player characters arrive in the town of Hommlet, not far from the former site of an evil temple, destroyed years before. The players find that agents of evil are at work infiltrating the little town, and are soon led to a supposedly abandoned moathouse, where they find a small dungeon filled with evildoers.

The basic idea of the module goes roughly as follows: The player characters arrive in the town of Hommlet, not far from the former site of an evil temple, destroyed years before. The players find that agents of evil are at work infiltrating the little town, and are soon led to a supposedly abandoned moathouse, where they find a small dungeon filled with evildoers.

After clearing it out, they soon conclude that the Temple of Elemental Evil is gathering its forces again. Going to the grimy town of Nulb near the old Temple, the players base themselves among thieves and thugs as they fight their way through several levels of monsters until, using the power of an ancient evil artifact, they overthrow the wicked force that powers the Temple.

At least, that’s what you’d figure was supposed to happen if you just read the module. Playing it out proved very different.

As the referee, I’ll cop to fostering some of that change. I noticed, for example, that the Temple was supposed to be recruiting brigands in the area. And that some of the non-player characters in the area of Hommlet were said to be in the process of building a tower of their own.

So I decided that the authorities in the area already had an idea that the Temple was gathering its forces, hence the tower; while the Temple was further along than the authorities knew, hence the brigands (and the agents within the town of Hommlet).

But it was when the players reached Nulb that things really went in an unexpected direction. Hearing of the evil reputation of the town, they sent in a thief to scout out the area. He ended up joining a local thieves’ guild. The other players came in later, at which point the paladin in the group decided it made sense for her to preach the gospel of Saint Cuthbert in the marketplace — the black marketplace, really.

This drew the attention of the Temple, who attacked the players that night … at the same time the thief undertook a potentially deadly mission for his guild … and the net result in both cases was a major fire.

When all was said and done, Nulb had burned to the ground.

Rather than leave it at that, though, the players decided to make the former site of Nulb a rallying-point against the Temple. They built fortifications in the ruins, and brought in residents of the countryside who were suffering from attacks by Temple forces.

Suddenly the dungeon crawl had turned into a bigger story: the characters forging a new community, while fending off the growing wickedness by raiding the Temple at its heart.

I ruled that due to the infighting of the (chaotic evil) Temple, most of their military forces — the brigands — were kept away from the real Temple, so that they wouldn’t become pawns in the conflict of element against element. So it was still possible for the PCs to raid the Temple and fight their way through the dungeons.

On the other hand, I added story elements to keep them distracted as they built up their New Nulb: meddling by the area’s designated political authorities; a mysterious tribe of humanoids on the outskirts of town; night attacks by forces of the Temple; former residents of Old Nulb, coming back to hunt out treasure they’d left behind in the fire; an illusionist seeking asylum, who had stolen a treasure from a nearby tribe of elves, who themselves rode into town seeking revenge (of course the whole thing was a dastardly plot by the Temple).

None of these things was anywhere in the text of the module. But they were all logical extrapolations, and solid story elements that gave the players the sense that the world was moving around them, and that their actions had consequences.

The dungeon-crawling aspects were still there, and still fun, but had added meaning. The text, it turned out, could be read in such a way as to create a narrative that was not obvious.

In the end, the campaign wrapped up earlier than I’d expected. As I touched on above, the adventure more-or-less assumed that the PCs would gather the components of an evil artifact, put it together, and carefully use it to a) gain power (by transporting to pocket dimensions, where they could win experience and treasure) and b) take them to a final confrontation with the demoness who ruled the Temple.

When my players found the component that was the core of the artifact, though, they at once decided to destroy the thing.

They found out how (full details are in the module), and managed to pull it off as the Temple launched a major assault on New Nulb. Beating back the assembled hordes, the characters returned to the now-partially-ruined Temple, made their way to the lair of the demoness, and engaged her in battle.

Which went very well; the demoness was scary, but not invincible; the characters all had their individual moments to shine and tie off their character arcs; and the good deity Saint Cuthbert had a little cameo to provide a helping hand.

In the end, the demoness was destroyed, the Temple collapsed into a deep pit, and the forces of Good had triumphed.

Just not in any way I could have predicted beforehand.

Players are, fundamentally, unpredictable beasts. They’ll do things you don’t — can’t — expect. There’s no reason to believe that somebody trying to come up with the structure of an adventure will in fact hit on one that means anything for your group of players. As a referee, if you’re going to try running a pre-generated adventure, you have to be flexible. You have to be prepared to follow your players. You have to be prepared to come up with challenges that aren’t in the module.

What I’ve found is that it’s easier doing this with an adventure that consists, essentially, of a dungeon. Let the players decide what they want to do with the place. Do they start clearing the evil out of it? Do they strike a bargain with one faction within the dungeon? Do they want to take it over, and try to turn it into a home of good?

Or do they just not want to bother, and follow another adventure hook instead?

The virtue of telling a story in a role-playing session is its unpredictability. As long as everybody at the table trusts each other to collaborate in good faith, then what happens by the end of the night ought to have the shape of a story to it. If that’s so, then a pre-determined storyline risks getting in the way.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

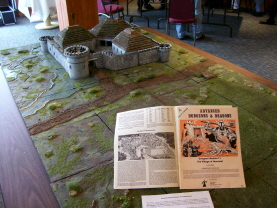

ToEE has a firm place in my gaming memories. I recall the DM hated Gygax’s maps for not conforming to grids, their jagged lines dancing across the page at strange angles. We would just sit back and laugh as the DM struggled to draw a battle map that resembled the original.

Other great adventures that I remember were Egg of the Phoenix and Child’s Play. Good times, good times. Thanks for the trip down memory lane.

On a side note, it’s too bad the ToEE computer game wasn’t as memorable and bug laden.

Its funny that you blog about this. I was about 4 sessions into The Red hand of Doom 3.5 module with my players and i was trying to run it dead on the book. It just wasn’t fun. I wasn’t having fun and i don’t think my players were having that much fun either. So with last saturdays sessions i decided to make it my own game and i changed everything. It made all the difference. I had way more fun and my players did as well. I am fairly new to DnD and have only played 3.5 and DMed 1 other game.

Hey Dave,

I remember Egg of the Phoenix! Only module the great Paul Jaquays ever did for TSR, if I remember correctly.

I heard conflicting things about the computer game version. Did you ever try the second, unofficial patch? I heard that improved things.

John

[…] and most especially The Temple of Elemental Evil, (which Matthew David Surridge examined in detail here), perhaps the finest RPG adventure module ever […]

[…] one of the most celebrated AD&D adventures and the first part of the notoriously difficult Temple of Elemental Evil mega-campaign, revised to run in the 4th Edition of Dungeons and Dragons. The new version was […]

[…] after all these years. Matthew David Surridge wrote a fascinating analysis for us in his article The Art of Storytelling and The Temple of Elemental Evil. The module has been converted to a popular computer game, and the opening chapter, The Village […]

[…] acclaimed story “The Word of Azrael” appeared in Black Gate 14. His very first post was “The Art of Storytelling and The Temple of Elemental Evil,” a look at how unpredictable stories spontaneously arise out of D&D sessions, using his […]

I know this is an old post, but it just got a new mention…

Raging Swan Press makes some excellent stuff for Pathfinder. Shadowed Keep on the Borderlands is an homage to Hommlett’s moat house, but “more.” For Hommlett fans, it is a very neat read/play.

http://www.ragingswan.com/shadowed-keep-on-the-borderlands/

[…] flies when you’re having fun. My first post on Black Gate went up a bit more than five years ago, a piece about storytelling, role-playing games, and what […]