Frayling Tackles his own Yellow Peril

The centennial of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu character is a topic I have covered both for the anniversary of the Devil Doctor’s first appearance in the story, “The Zayat Kiss,” in 1912 and the publication of the first novel (really a fix-up of stories), The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu, in 1913.

The centennial of Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu character is a topic I have covered both for the anniversary of the Devil Doctor’s first appearance in the story, “The Zayat Kiss,” in 1912 and the publication of the first novel (really a fix-up of stories), The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu, in 1913.

While Rohmer and the character are largely forgotten outside of pulp circles today, the legacy of the criminal mastermind is alive and well in film and comics. The concept of the Yellow Peril from an era when the broad term Oriental grouped together people from parts of Eastern Europe with all of Asia and the Middle East may sound anachronistic, but given the continued delicate relations between the Middle East and the West, those same fears personified are still the stuff of fiction and paranoia well over a century on.

Sax Rohmer did not invent the criminal mastermind, nor was he the first to capitalize on the Yellow Peril for works of fiction. What he did do was create an archetype that managed to embody and transcend the fears of a “foreign other” to instead personify the fear of Western society falling to a superior intellect operating under a completely different set of values. Rohmer did this better than anyone before and while Fu Manchu as a name may seem ridiculous, the concept of the character is still with us from James Bond films to the media’s portrayal of terrorist leaders in the 21st Century.

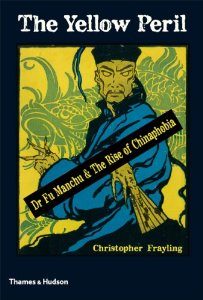

Sir Christopher Frayling is unquestionably one of the finest cultural historians on the planet. His articles and books on topics as diverse as vampires and spaghetti westerns are brilliant and definitive. He has been working, in fits and starts, on a book examining the Yellow Peril in general and Sax Rohmer in particular for over four decades. What little he published on the subject over the years proved tantalizing. So it was that I greeted this second of three major English-language works timed to capitalize on the character’s centennial with the highest of expectations.

Sir Christopher Frayling is unquestionably one of the finest cultural historians on the planet. His articles and books on topics as diverse as vampires and spaghetti westerns are brilliant and definitive. He has been working, in fits and starts, on a book examining the Yellow Peril in general and Sax Rohmer in particular for over four decades. What little he published on the subject over the years proved tantalizing. So it was that I greeted this second of three major English-language works timed to capitalize on the character’s centennial with the highest of expectations.

Ruth Mayer’s Serial Fu Manchu was the first such book to see print, while an anthology of essays by various commentators (including Frayling), Lord of Strange Deaths, has been indefinitely delayed by the publisher.

Frayling’s The Yellow Peril may have arrived a year late for the official centennial, but the very thought of a Frayling tome digging deep into the subject was certainly worth waiting for…or should have been.

The book is not terrible, but it is unfocused. Reading more like a collection of several articles on inter-related topics, the author fails to reach any conclusions. The book ends literally with an excerpt from a Paul Magrs Fu Manchu parody. No disrespect to Mr. Magrs, who is a fine author, but the last few pages are little more than a sloppily arranged cataloging of the character’s more high-profile appearances in the past thirty years and little more.

Part of the problem is Frayling is unable to reconcile his lifelong fascination with the author and the character with his very real liberal guilt that he shouldn’t be enjoying this sort of thing. He goes so far as to note disapprovingly that Titan Books are reprinting the original novels for a new generation. Frayling possesses a copy of Rohmer’s first book, the extremely rare Pause! (1910), and provides some enlightening excerpts from the book. While this is an undoubted highlight for Rohmer fans, it also paints Frayling in the unflattering light of an elitist who can secretly enjoy his Rohmer collection (much of which is described and illustrated in the text and accompanying photo-inserts), while still noting it is contraband material unsuitable for general consumption. The end result calls to mind the Nazi collectors with their treasured stash of banned works and certainly isn’t the impression one expects the author wanted to leave with readers.

There is a lengthy chapter on the handover of Hong Kong and the unflattering media coverage. There is a well-written biographical section on Rohmer’s life, emphasizing his music hall work and influences and noting he was an unreliable source of autobiographical detail. Inexplicably, Frayling than falls into the same trap by imagining Rohmer as the author of Yellow Peril newspaper accounts (written over a year earlier than Rohmer’s highly questionable claims that he worked as a journalist in Limehouse). It is as if Frayling takes the notion of the Yellow Peril personified in one character and transposes it by taking racist “yellow journalism” and personifying it in one author. The book also features a lengthy chapter on Charles Dickens’s prejudices against the Chinese before concluding with a detailed examination of Fu Manchu in comic strips, comic books, film, radio drama, and television.

There is a lengthy chapter on the handover of Hong Kong and the unflattering media coverage. There is a well-written biographical section on Rohmer’s life, emphasizing his music hall work and influences and noting he was an unreliable source of autobiographical detail. Inexplicably, Frayling than falls into the same trap by imagining Rohmer as the author of Yellow Peril newspaper accounts (written over a year earlier than Rohmer’s highly questionable claims that he worked as a journalist in Limehouse). It is as if Frayling takes the notion of the Yellow Peril personified in one character and transposes it by taking racist “yellow journalism” and personifying it in one author. The book also features a lengthy chapter on Charles Dickens’s prejudices against the Chinese before concluding with a detailed examination of Fu Manchu in comic strips, comic books, film, radio drama, and television.

Frayling’s inexplicable lack of narrative cohesion and failure to tie his disparate essays together by reaching an actual conclusion on the subject makes the book a very minor one in the author’s otherwise impressive body of work. Frayling’s title was expected to be the definitive cultural study of the Yellow Peril and how it informed western pop culture and thinking more than a century on. Happily, that book already exists in Ruth Mayer’s Serial Fu Manchu. Every so often, a David comes along and topples a Goliath. Mayer’s serious academic treatise achieves just that feat. Here’s hoping a few decades on, her work will be the one turned to by serious students of history, sociology, and popular culture.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press) and The Destiny of Fu Manchu (2012; Black Coat Press). The Triumph of Fu Manchu is coming soon from Black Coat Press.