My Fantasia Festival, Day 10: Once Upon a Time in Shanghai and Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart

I’m going to do something a little different in this instalment of my diary of the Fantasia film festival: I’m going to write about two movies in the reverse order from which I saw them. I watched both on Saturday, July 26, and it so happened that the second one struck me as a perfectly fine movie of the sort of movie that it was, while the first seemed a little bit more.

I’m going to do something a little different in this instalment of my diary of the Fantasia film festival: I’m going to write about two movies in the reverse order from which I saw them. I watched both on Saturday, July 26, and it so happened that the second one struck me as a perfectly fine movie of the sort of movie that it was, while the first seemed a little bit more.

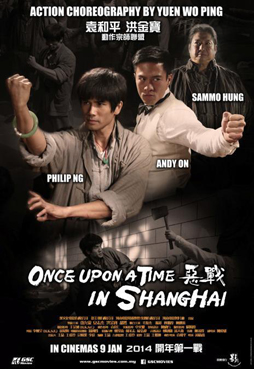

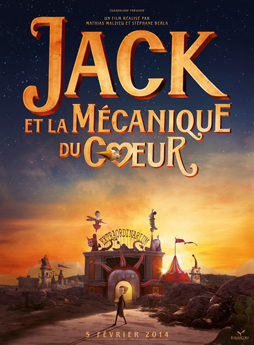

The second movie was the Canadian premiere of Once Upon a Time in Shanghai (original title: E Zhan), a martial-arts film set in 1930, featuring warring gangsters, a humble youth from the countryside, and sinister Japanese agents trying to gain control of the Shanghai underworld. It was directed by Wong Ching-Po, written by Wong Jing, boasted fight choreography by Yuen Wo-Ping, and starred Philip Ng as the heroic rustic Ma Yongzhen, Andy On as a charismatic gangster alternately Ma’s enemy and friend, and veteran actor Sammo Hung in a major supporting role as Ma’s mentor. The first movie was an animated musical from France called Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart (Jack et la mécanique du coeur), co-directed by Mathias Malzieu and Stéphane Berla; Malzieu also wrote the film and performed the voice of the main character. It’s not a perfect movie, but it had a blend of style and imagination I found quite powerful.

But let’s start with Shanghai (a remake of 1972’s Boxer From Shantung [Ma Yong Zhen]). As I said, it’s a perfectly fine movie that does just what it says on the tin: provides for lots of distinctive martial-arts fight scenes against a 1930s period setting, with a distinct patriotic subtext — even the gangsters are opposed to the Japanese or Westerners controlling Shanghai or China. A broad mix of action, comedy, and melodrama, it played in the big Hall Theater and the audience cheered the fights and laughed when they were supposed to and generally had a good time.

The period setting is very well done, with elaborate costumes — specifically in a number of scenes set in a nightclub one of the gangsters controls. There’s a nice visual texture to the movie overall, which is to say that everybody always has a cigarette lit and there’s always a lot of smoke in the air. The fight scenes are nicely shot, with shifts from slow to fast motion, but do overuse the narrow-shutter strobing effect (seen in things like Gladiator and Saving Private Ryan).

The period setting is very well done, with elaborate costumes — specifically in a number of scenes set in a nightclub one of the gangsters controls. There’s a nice visual texture to the movie overall, which is to say that everybody always has a cigarette lit and there’s always a lot of smoke in the air. The fight scenes are nicely shot, with shifts from slow to fast motion, but do overuse the narrow-shutter strobing effect (seen in things like Gladiator and Saving Private Ryan).

The acting’s cartoony but effective. On’s charismatic gangster Long Qi is particularly strong. The plot tends to amble along, setting him and Ma against each other early on as a way of building their relationship, then bringing out the real villains of the piece. The movie’s entertaining enough that this avoids being frustrating. I will say there’s a surprising absence of guns for a picture about gangsters, but then that’s part of the genre — along with the way minor characters line up to fight the hero one by one rather than rushing him all at once.

Once Upon a Time in Shanghai mainly stands out due to its look. The movie nicely establishes what it calls “a city of dreams for all Chinese people,” creating a 1930s feel in architecture, fashions, and prop designs. Personally, I thought it was marvellously appropriate to this type of story, as to my eyes it evoked the feel of a pulp adventure story — which is essentially what this sort of martial-arts tale is. There are broad heroes, equally broad villains, and conflicts which are easily resolved through fight scenes. More: those fight scenes structurally do what fight scenes in an action movie are supposed to do, summing up character, advancing plot, and crystallising theme exactly in the way musical numbers do in a musical. This movie knows what it is, knows how its genre works, and does its job skilfully.

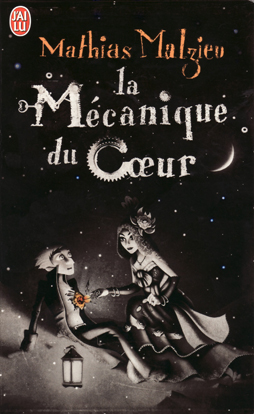

There is a sense in which Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart is less precise about its form. It’s a musical, but the songs sometimes seem to be placed a little more randomly. The story began as a concept album from Malzieu’s band Dionysos, then was turned into an illustrated novel (with a cover by revered French comics artist Joann Sfar), then was adapted for the screen. Whether due to the process of adaptation or not, the story seems occasionally ungainly, moving quickly across important plot points or encounters; but there’s an inventiveness that I feel carries the film.

There is a sense in which Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart is less precise about its form. It’s a musical, but the songs sometimes seem to be placed a little more randomly. The story began as a concept album from Malzieu’s band Dionysos, then was turned into an illustrated novel (with a cover by revered French comics artist Joann Sfar), then was adapted for the screen. Whether due to the process of adaptation or not, the story seems occasionally ungainly, moving quickly across important plot points or encounters; but there’s an inventiveness that I feel carries the film.

It opens with a woman climbing a hill above 19th-century Edinburgh, here a city of gothic steeples. It’s the coldest day in the world, and the woman’s going to a local midwife to give birth. She makes it to the midwife, but there are complications with her newborn boy’s heart; luckily the midwife’s also something of an inventor, and is able to replace the boy’s heart with a cuckoo clock. The mother vanishes, and the midwife takes the boy, Jack, as her own. Jack grows up with her, forced to follow three rules to keep his heart operative: he can’t touch it, he must always hold his temper in check, and whatever he does, he mustn’t fall in love. Of course he breaks the rules. As an adolescent he meets a beautiful young singer, and loses her, and sets out to recover her, travelling to Paris and Andalusia and signing on with a carnival and coming in conflict with an old rival.

Whether you like this movie or not will correlate strongly with your feelings about Tim Burton. The look and feel of the film is strongly, strongly influenced by Burton’s design sense. It’s more colourful, and I felt more visually inventive than anything I’ve seen by Burton (if it helps, it actually reminded me of Skottie Young’s comics almost as much). I will go so far as to say that at times it seemed to touch the mythopoeic fairy-tale feel of Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête. Not always, but occasionally, and that’s something in and of itself.

Whether you like this movie or not will correlate strongly with your feelings about Tim Burton. The look and feel of the film is strongly, strongly influenced by Burton’s design sense. It’s more colourful, and I felt more visually inventive than anything I’ve seen by Burton (if it helps, it actually reminded me of Skottie Young’s comics almost as much). I will go so far as to say that at times it seemed to touch the mythopoeic fairy-tale feel of Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête. Not always, but occasionally, and that’s something in and of itself.

It may even help the film that the plot doesn’t always seem perfectly rationalised: there’s a kind of dreamlike air that develops. Of course the Byronic Joe turns out to be Jack’s rival; we get the idea from his designs and voice and musical accompaniment without the need of a scene that bluntly establishes their conflict over the beautiful Miss Acacia. Of course Jack is pursued on a train between Edinburgh and Paris by Jack the Ripper, and of course he’s saved by Georges Méliès. You couldn’t predict it, but in hindsight it makes perfect intuitive sense in this strange and wonderful steampunk fairy-tale reality.

The film’s use of Méliès helps bring out the power of its central idea, the cuckoo-clock heart, and also to get at something perhaps central to steampunk in general. Méliès, the inventor of fantasy movies and of film special effects, describes Jack’s heart as a machine with emotions inside; of course he links it to the machine he’s playing with, the film camera (as the movie also links it to the barrel-organ Miss Acacia is playing when Jack meets her). Méliès goes on to become a mentor figure to Jack, a wizard who travels with him for a while; a wizard who knows how to get effects out of machines. How to find the emotions inside the machine. It’s a great conceit; somehow the use of this specific historical figure (shades of The Invention of Hugo Cabret) helps to make the fairy-tale more fantastic.

Of course the movie’s plenty fantastic to start with, filled with memorable images. A cat wearing glasses. A liqueur made of tears. A winged accordion-like train. Scene transitions, dream sequences, wild travel montages: it’s a quick, delirious build of fantastic image after fantastic image. And it all builds from the basic animation style and design conception — the CGI characters all look like porcelain puppets, and move as though animated in stop-motion. As though they were effects in a Méliès film. It’s marvellously effective.

Of course the movie’s plenty fantastic to start with, filled with memorable images. A cat wearing glasses. A liqueur made of tears. A winged accordion-like train. Scene transitions, dream sequences, wild travel montages: it’s a quick, delirious build of fantastic image after fantastic image. And it all builds from the basic animation style and design conception — the CGI characters all look like porcelain puppets, and move as though animated in stop-motion. As though they were effects in a Méliès film. It’s marvellously effective.

The conclusion’s bittersweet, which is foreshadowed but unexpected. It’s tempting to say that in an American film the plot would turn on finding a way to break the rules and get away with it, while this movie, being a French film, isn’t interested in evading the rules but in choosing to break them and accept the consequences as an existential act. But the reasons for the creative choice don’t matter, only the result; and the result here is an elegaic ending that gives the film a final heft. It’s a strong decision, and it works.

I found Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart touching and constantly inventive. If you’re willing to accept certain plot points without their explicit detailing, if you’re willing to get onboard with the movie’s dreamlike structure and style, you’ll find the same. I think the movie encourages the viewer to abandon the rational and accept what they see. I think it’s something worth experiencing.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] My Fantasia Festival, Day 10: Once Upon a Time in Shanghai and Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart […]