Confessions Of a Cormanite

Graham Greene once said that the books that influence us the most are not the ones that we “seriously” or systematically read in adulthood, but are rather those first books we seek out in our youth and that we read for the simple love of reading.

Graham Greene once said that the books that influence us the most are not the ones that we “seriously” or systematically read in adulthood, but are rather those first books we seek out in our youth and that we read for the simple love of reading.

He wrote, “In later life, we admire, we are entertained, we may modify some views we already hold, but we are more likely to find in books merely a confirmation of what is in our minds already.” But when we are children, “all books are books of divination, telling us about the future, and like the fortune-teller who sees a long journey in the cards or death by water they influence the future.” This has been true of my own reading, and I would also assert that for those who love film, it equally applies to the movies that they watched early in their lives.

Movie buffs come in countless varieties; there’s a great variation in their degrees of passion and in the objects of their devotion. Some bring offerings of ice to the shrine of a Kubrick or an Antionioni, and others make blood sacrifices on the altar of a Scorsese or a Peckinpah. Some soar with Hawks while others go to Welles for their refreshment. One group bows silently before Buster Keaton and the next sings songs of praise to Judy Garland.

Now, I am a movie buff and I have been given tremendous pleasure by the artists I just mentioned and by many others. I love Lubistch, would stay up late for Sturges, have been beguiled by Bunel, am wild for Wilder… but none of these immortals occupy the place closest to my heart.

Get me away from the art house, put away the beautifully illustrated coffee table book on the Masterpieces of Swedish Cinema, send home the educated — but dull — guest whose favorite Woody Allen film is Interiors (please!) or who saw The English Patient three times, and leave me alone in my sanctuary — my darkened living room at 2:00 am, lit only by the restless images that pass across the television screen, images selected for no one’s pleasure but my own, and the truth will at last emerge. I am a Cormanite.

[Click on the images for bigger versions.]

I fell under the spell of Roger Corman in the early days of my moviewatching, the late 60’s and on through the 70’s. It’s getting difficult now to remember those primitive days before VCR’s, DVD’s, Blu-rays, Netflix, Hulu, Youtube, tablets, or any of the other ways now available to watch whatever you want whenever you want. (In those days streaming was what you ran off to do during a late night used car commercial, before the movie came back on.)

“Home video” then was turning on your television set and making a choice between whatever it was the available broadcast channels were offering at that moment. If you didn’t like that, tough; you could read something or make conversation with a family member, both activities which for many have become as remote and alien as the cave paintings at Lascaux.

“Home video” then was turning on your television set and making a choice between whatever it was the available broadcast channels were offering at that moment. If you didn’t like that, tough; you could read something or make conversation with a family member, both activities which for many have become as remote and alien as the cave paintings at Lascaux.

I grew up in Bell Gardens, California, a blue collar suburb twelve miles south of downtown Los Angeles, which meant that my TV options were lavish compared to those of many people in other parts of the country, folks who didn’t live in such a large media market. I had the network channels (only three in those days) 2, 4, and 7, plus four local independents, 5, 9, 11, and 13.

Add to that the PBS channel (28) and a couple of other UHF’s (52 and 56, but reception was spotty) and the result was a lot of viewing potential — more than I could reasonably handle, in fact, what with the intrusions of school and family and the rest of what could ironically be called “real life.”

The lack of any kind of home recording meant that painful choices often had to be made. When the TV Guide arrived, I would immediately grab a pen and carefully go through the coming week, day by day, circling the movies I planned to watch. For all of the channels I mentioned late nights and weekends were largely filled up with old movies, (prime-time weeknights too, for the independent stations) and no recording meant that annotation of the TV Guide was very important, because I didn’t know when I would again have a chance to see The Adventures of Robin Hood or The Bank Dick or The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

The real problem arose when two (or even more) movies were scheduled by different channels at the same time. Every week presented impossible dilemmas: Tower of London or The Awful Truth? The Maltese Falcon or Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Road to Morocco or To Hell and Back?

These are choices no one should ever have to make; I did the best I could, but the experience left emotional scars that linger to this day. I still sometimes awaken in the early hours of the morning, with a vague sense of guilt over that Saturday night in 1975 when I chose Lord Love a Duck over The Crimson Kimono…

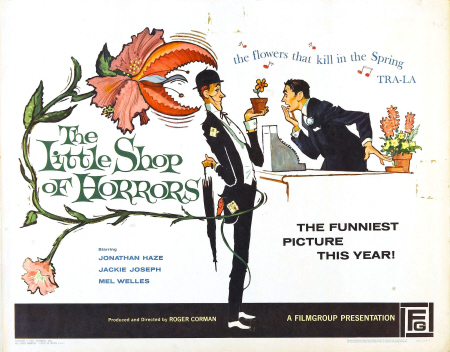

It was in this fevered atmosphere that I saw my first Roger Corman movie, The Little Shop of Horrors, sometime around 1969 or 1970. Admittedly, I was then just an inexperienced kid, but still — it was the damndest thing I’d ever seen. I was hooked, and began searching out more movies by this Corman guy, and on late-night movie TV in those days, that wasn’t difficult to do; I began collecting viewings of Corman movies the way mountaineers collect the peaks they’ve climbed.

It was in this fevered atmosphere that I saw my first Roger Corman movie, The Little Shop of Horrors, sometime around 1969 or 1970. Admittedly, I was then just an inexperienced kid, but still — it was the damndest thing I’d ever seen. I was hooked, and began searching out more movies by this Corman guy, and on late-night movie TV in those days, that wasn’t difficult to do; I began collecting viewings of Corman movies the way mountaineers collect the peaks they’ve climbed.

The culmination of those years came sometime in 1976 or 77. Channel 5 was then in the habit of showing the same movie every night for a week, at 8:00 pm. What the programming strategy behind this was I couldn’t imagine then and can’t imagine now. But I loved it. After watching The Caine Mutiny for five nights in a row, I got my hands on some ball bearings and drove my mother insane, rattling them in my hand as I restlessly roamed the house, muttering about strawberries. Five nights of Duck Soup elevated me to a worker’s paradise the most fervent Marxist can only dream about.

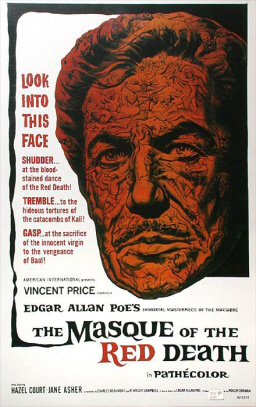

And then came the week channel 5 offered Roger Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death every night for a week, Monday through Friday. Rarely in my life have I known such bliss. By the end of that week, every time I looked into a mirror, I would see Vincent Price gazing out of it. It was an almost religious experience; after years of studying the catechism, I had finally received my Corman Confirmation.

In a career that began in 1954 and isn’t over yet, Roger Corman has produced over 400 films and has directed 56. Throughout those years, Corman has proven himself a master of genre; in addition to the science fiction and horror movies that most people think of when they hear his name, he also tried his hand at western, teen rebellion, historical melodrama, sword-and-sandal, gangster, biker, offbeat comedy, and social protest films.

Almost all of these movies exhibit the twin hallmarks of Corman productions: they were made fast and they were made cheap. Many were made on shooting schedules of just two or three weeks or less (The Little Shop of Horrors has entered legend by being shot in two days) and on… shall we say, spartan budgets. For instance, 1958’s Teenage Caveman cost about $70,000, (though watching the movie today, you wonder where the hell the money could have possibly gone — rocks don’t cost anything), while a relatively lavish color production like 1960’s House of Usher still came in at a modest $200,000, making it a very inexpensive film even in those days.

Almost all of these movies exhibit the twin hallmarks of Corman productions: they were made fast and they were made cheap. Many were made on shooting schedules of just two or three weeks or less (The Little Shop of Horrors has entered legend by being shot in two days) and on… shall we say, spartan budgets. For instance, 1958’s Teenage Caveman cost about $70,000, (though watching the movie today, you wonder where the hell the money could have possibly gone — rocks don’t cost anything), while a relatively lavish color production like 1960’s House of Usher still came in at a modest $200,000, making it a very inexpensive film even in those days.

There’s no disputing the badness of a lot of these movies; lack of adequate time and money are handicaps that will leave their mark one way or another. But even so, the best of these movies — and even some of the worst — display a degree of wit, energy, inventiveness, and ambition entirely absent from the work of other purveyors of cheap schlock like William Castle (who I also have a great fondness for, but that’s another article). Talent will make itself shown, even in the most difficult circumstances, and talent is something Corman definitely does possess, though he’s not a fanatic about it.

That’s just another one of his charms, and it’s only honest to admit that even when more time and money were available, after he left American International and formed his own production company, New World Pictures, he stuck to his old methods. Working up against the wall just seems to be in his nature; he’s like a daredevil who isn’t content to simply to walk a tightrope across Niagara Falls — he has to do it backward, blindfolded, and with a skunk sitting on his head. (Also, the testimony of countless witnesses establishes the fact that Corman’s mania for economy goes well beyond mere thriftiness — the man is just cheap.)

I certainly don’t have room to go over Roger Corman’s whole output, but here are a few of my favorite peaks in the mighty Corman Range.

The Little Shop of Horrors

This was my introduction to Corman and it’s a genuinely twisted little movie.

Like many Corman films, it was written by Charles Griffith. Principal photography was finished in two days, with a small number of retakes done later.

The movie is probably best remembered for a young Jack Nicholson’s portrayal of undertaker Wilbur Force, a giggling, masochistic dental patient. “Now, no novocain — it dulls the senses!” Force says, as Seymour Krelboyne (Jonathan Haze) gets to work on him.

Seymour is no dentist — he’s accidentally killed the real dentist a few minutes before and is trying to cover up — but that doesn’t matter to Force. “This is gonna hurt you more than it is me,” Seymour says, applying the drill.

“Oh, goody, goody! Here it comes!” Force gushes, then starts squirming and shrieking in delight as Seymour destroys his teeth. Nicholson is funny and creepy in equal measure, so successfully — and uncomfortably — so, in fact, that it’s a miracle he ever got another acting job after this.

This movie, of course, is about Audrey, a mutant plant raised by Seymour, who works at Mushnick’s Flower Shop. (Mushnick is ably played by Mel Welles. I like to imagine the cast and crew’s excitement when Corman told them that he had gotten Welles for his picture. “We’ll all be working with Orson Welles?! Roger, That’s wonderful!” “Orson? Who said anything about Orson? Everyone, meet Mel!”)

Audrey craves blood, and is continually crying, in a petulant, cajoling tone familiar to the parents of every toddler, “Feed me! I’m hungry!” Seymour winds up killing people to chop up and give to the insatiable plant. (Always accidentally — he’s a total schlemiel who’s unsuccessful at anything he actually tries to do.)

Audrey craves blood, and is continually crying, in a petulant, cajoling tone familiar to the parents of every toddler, “Feed me! I’m hungry!” Seymour winds up killing people to chop up and give to the insatiable plant. (Always accidentally — he’s a total schlemiel who’s unsuccessful at anything he actually tries to do.)

This leads to the scene that puzzled me most when I first encountered this film at the tender age of nine. Seymour is taking a nighttime walk, trying to “find food for master.” (By this time, the poor jerk has been completely browbeaten by a shrub.) He encounters a lady of the evening (Meri Welles) and confuses her business proposition with volunteering to be eaten by Audrey.

To resolve the age-old question, “My place or yours?” Seymour spits on a big rock (he doesn’t have a coin to flip) and tosses it in the air; it comes down on the hooker’s head and, voila! Food for master.

My fourth-grade self knew that some strange and significant transaction was taking place here, but what the exact nature of it was I couldn’t quite figure out. Ah, the innocence of youth!

After seventy one minutes, the story ends badly for Seymour, but it’s been worthwhile for us; the movie is quite funny and it looks as if everyone enjoyed themselves immensely. (And I haven’t even mentioned the note-perfect Dragnet parody that develops when the cops get involved.) One day, this thing will be a part of the Criterion Collection — mark my words.

It Conquered the World

Western actor Lee Van Cleef (if you’ve ever seen The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly you’re familiar with every sweat-clogged pore in his scowling face) plays “illustrious physicist” Dr. Tom Anderson, a surly type who neglects his wife Claire (the beautiful Beverly Garland) to sit up late at night, obsessively occupied with a tableful of electronic equipment. No, he’s not doing that — he’s in radio contact with an alien from Venus!

The plot of the movie has to do with Anderson’s selling out the human race to the evil extraterrestrial invader (he’s convinced that the ultra-intelligent, emotionless Venusian will save us from ourselves — yeah, right.)

After a lot of speechifing and mind-controlling bats and panicked stampeding, humanity is ultimately saved by margarine-flavored Peter Graves (as rocket scientist Dr. Paul Nelson) and a wised-up Anderson — after Claire has been killed by his alien pal, and after a little bit (okay, a lot) of light-fingered lifting from The Day the Earth Stood Still and Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

The script is all thumbs (co-author Charles Griffith, called in to do a complete rewrite only two days before shooting, wouldn’t even let Corman put his name in the credits), but the movie has two incomparable glories: Beverly Garland and the Venusian monster.

Beverly Garland (who made four films with Corman) was an utterly assured performer who acted every part, no matter how silly, with unforced strength and conviction. She worked steadily, mostly in television, from 1950 until just a few years before her death in 2008.

She had the talent to be a major actress; why her career wasn’t more substantial — in terms of quality projects — is an unanswered question (perhaps, having started in low budget pictures, people wrongly assumed that was where she belonged), but if you want to see what she could do, take a look at her portrayal of Mrs. Stepanek in 1968’s Pretty Poison with Anthony Perkins and Tuesday Weld.

Mrs. Stepanek is a more frightening monster than any you can find in a SF or horror movie; she’s a Mother from Hell, sadistic and controlling, and Garland depicts her with an icy viciousness that would send Joan Crawford fleeing back to the dry cleaner to cower under the counter.

In It Conquered the World, Garland plays Claire with an unwinking seriousness that never becomes stiff or parodic, as happens to some actors when they’re stuck in a movie that’s as inherently ridiculous as this one. She’s by far the most appealing, spirited character in the film, and is the tale’s real heroine — far more than Van Cleef’s wolfish Anderson or Peter Grave’s Paul Nelson, who has all the appeal of an ironing board.

When her spouse runs out to hook up with his new alien buddy for a night of interplanetary bonding, Claire grabs the microphone of her hubby’s radio set and, calling the interfering extraterrestrial, strikes a blow for every wife who’s been abandoned once too often for semipro hockey or poker night: “Look, I don’t know whether you can hear me or not but if you can you listen good — I hate your living guts for what you’ve done to my husband and my world! I know you for the coward you are and I’m going to kill you! Do you hear that?! I’m gonna kill you!”

When her spouse runs out to hook up with his new alien buddy for a night of interplanetary bonding, Claire grabs the microphone of her hubby’s radio set and, calling the interfering extraterrestrial, strikes a blow for every wife who’s been abandoned once too often for semipro hockey or poker night: “Look, I don’t know whether you can hear me or not but if you can you listen good — I hate your living guts for what you’ve done to my husband and my world! I know you for the coward you are and I’m going to kill you! Do you hear that?! I’m gonna kill you!”

It should be laughable, but Beverly Garland’s razor-edged intensity punches a hole in the screen; you believe that she means every word of it. Try that, Meryl Streep!

When Claire arrives at the alien’s hide out (“Elephant Hot Springs Cave” — with an atmosphere just like Venus!), we finally see the monster. Built by Paul Blaisdell from Corman’s own idea, the Venusian is a squat, conical critter that’s all grinning face; it has two big, claw-tipped arms but no feet. (It must have been a lot of fun squatting underneath the thing, shuffling around to make it move.) Corman wanted the alien low to the ground because he mistakenly thought that Venus has a higher gravity than Earth (whoops). Correct shape or not, the monster’s construction must have led to a nationwide foam-rubber shortage.

It is unarguably one of the goofiest looking creatures in the history of low budget science fiction movies, and that’s saying something, but its very ridiculousness is distinctive and memorable. Sixty years from now, who’ll care about the stereotypical CGI aliens from today’s movies? They’re all the same. This monster you’ll remember. (But Beverly Garland’s reaction to it is too good not to record. When she first saw it, she said, “That conquered the world?” Then she kicked it over.)

By the way, the movie was remade ten years later by Larry Buchanan as Zontar, the Thing From Venus. You know better than to watch that, right?

The Masque of the Red Death

Between 1960 and 1964, Roger Corman directed seven films based on the works of Edgar Allan Poe. (Some people include 1963’s The Haunted Palace in the Poe cycle, but it’s actually based on a Lovecraft story.) By this time, Corman was a proven moneymaker for American International Pictures and his budgets on these Poe pictures were substantial — by AIP standards, that is.

They’re all great fun. Many people (Martin Scorsese among them) would name the last Corman Poe, 1964’s The Tomb of Ligea, as the best of these films, and in a technical sense it probably is. But my favorite is the Poe that immediately preceded it, The Masque of the Red Death. It’s a movie with many virtues.

The script, by R. Wright Campbell and fantasy great Charles Beaumont, is necessarily episodic, stitching together as it does two different stories — the title tale of hubristic downfall and Poe’s sardonic take on patronage and revenge, “Hop Toad.” But the characterization is subtle and the dialogue is sharp and nuanced. The two stories wind up complimenting each other quite well, as the dwarf Hop Toad’s selfless devotion to the dancer Esmeralda provides a commentary on and a condemnation of Prince Prospero’s aesthetic egoism.

The film looks wonderful; Corman himself called it the most “lavish” of his movies. It was shot in England on a four week schedule, but wound up taking five, because, as Corman complained, he couldn’t get the English crews to work as fast as his American ones.

Production design was by Daniel Haller, who did production design or art direction on many Corman films, and who was a master of making a movie look more expensive than it was. He had access to medieval sets left over from Beckett, and used them to excellent effect. Cinematography was by Nicholas Roeg, later to become a director himself with such films as Don’t Look Now and The Man Who Fell to Earth. The camera movements in Masque are unusually graceful and fluid, as the lens drifts through the multi-chambered, multi-level set like a restless, eavesdropping spirit.

The performances are generally very fine. Jane Asher (who was the girlfriend of a bloke named Paul McCartney at the time) does well enough with the peasant girl Francesca, who is the object of Prospero’s corrupt desire, and David Weston, as her lover Gino, credibly conveys an emotional young man’s swings between bluff courage and abject fear.

Hazel Court, as the Prince’s consort Juliana, fulfills her usual role of providing all the neckline-plunging pulchritude the producers could get away with. Patrick Magee is a convincingly oily villain in the role of the sybaritic noblemen Alfredo, at least until he’s trussed up in an ape suit and set on fire; then he shrieks and thrashes most admirably.

Hazel Court, as the Prince’s consort Juliana, fulfills her usual role of providing all the neckline-plunging pulchritude the producers could get away with. Patrick Magee is a convincingly oily villain in the role of the sybaritic noblemen Alfredo, at least until he’s trussed up in an ape suit and set on fire; then he shrieks and thrashes most admirably.

Three performances truly stand out. Skip Martin plays Hop Toad as a man whose small body conceals a person of large intellect, large devotion — and large pride. When Alfredo slaps Esmeralda, Hop Toad feels the blow, and Martin lets us see the man’s tamped-down rage.

Then when he plays on Alfredo’s vanity to effortlessly maneuver the unsuspecting nobleman into the ape suit that will be his funeral pyre, Martin doesn’t overplay the moment or arch his eyebrows at the audience like a cheap Iago; he keeps himself reigned in. His release will come only when Alfredo is dead. You find yourself looking forward to Martin’s every appearance; from start to finish, it’s a marvelous and moving performance.

As the Red Death himself, John Westbrook is hooded, masked, and robed for the whole movie; using minimal gestures and walking with a slow and tranquil step, he’s limited to acting almost entirely with his voice — and a most effective voice it is. When he proclaims the beginning of the Dance of Death, his voice is full of ringing authority; when he confronts Prospero in the black room and informs the puzzled Prince that he is not a common human guest, there to enjoy the revels, his voice holds a note of melancholy regret with just a hint of shyness in it.

When Prospero presumptuously calls him the Ambassador of Satan, his rebuff, “He is not my master — Death has no master,” drops Prospero’s temperature — and ours — with its tone of cold, inflexible reproof. It’s surely a difficult job to play a symbol, an abstraction, an allegorical figure; Westbrook carries it off with a panache that comes from his very restraint and stillness.

When Prospero presumptuously calls him the Ambassador of Satan, his rebuff, “He is not my master — Death has no master,” drops Prospero’s temperature — and ours — with its tone of cold, inflexible reproof. It’s surely a difficult job to play a symbol, an abstraction, an allegorical figure; Westbrook carries it off with a panache that comes from his very restraint and stillness.

Which leaves Vincent Price. Many movies in the 60’s and 70’s — many of them Corman’s own — were enlivened by Price’s special brand of raspberry-sherbet villainy, and Price was never afraid to push an absurd part or premise to its limit. That’s part of what makes him so much fun to watch. Prospero, however, is not a silly or over-the-top character; the role calls for more moderation than his other Poe parts, and Price recognized that and responded with one of his very best performances.

Prospero is a seeker after truth and has found it (he thinks) in devil-worship. He is a man whose intellectual honesty has led him to indulge in acts of sadism and cruelty, because he believes that such harshness reflects the true nature of the world.

At the same time, that honesty prevents him from forcing Francesca to submit to him, and her steadfast hold on her own faith almost leads him to doubt his own. He can have a child’s father killed but can order the sparing of the child; in Prospero’s view the father has chosen his path of blindness and hypocrisy, while the untarnished child hasn’t yet had that opportunity. All of the film’s other excellences aside, Prospero is the key to the movie; if Price’s performance doesn’t work, The Masque of the Red Death doesn’t work. Thanks to Price’s intelligence and his appreciation of a more subtle role than he usually received, the movie works and works beautifully.

The Masque of the Red Death is full of striking and memorable moments: Prospero’s soliloquy on terror, delivered to the slow ticking of a razor-pendulumed clock; Juliana’s surrealistic nightmare of her own repeated human sacrifice — the price of becoming the bride of Satan — and her bloody death immediately thereafter (and Prospero’s sardonic injunction to his guests: “I beg you, do not mourn for Juliana; we should celebrate. She has just married a friend of mine.”)

The Masque of the Red Death is full of striking and memorable moments: Prospero’s soliloquy on terror, delivered to the slow ticking of a razor-pendulumed clock; Juliana’s surrealistic nightmare of her own repeated human sacrifice — the price of becoming the bride of Satan — and her bloody death immediately thereafter (and Prospero’s sardonic injunction to his guests: “I beg you, do not mourn for Juliana; we should celebrate. She has just married a friend of mine.”)

There is Afredo’s immolation, as the revelers silently look up at him with grotesquely masked faces; Prospero’s pursuit of the eerie, gliding red figure through rooms of yellow, purple, white, and black; Prospero’s pleading with the Red Death for the life of Francesca and the look of amazement on the prince’s face as she hesitantly, gently kisses him on the cheek when she leaves (Prospero won’t live long enough to process the fact that she’s just refuted his whole worldview); the Dance of Death, as the solemn red figure passes unnoticed among the revelers, leaving the blood-stained dancers slowly revolving to the macabre, stately grandeur of composer David Lee’s death waltz; the dying dancers slowly, slowly sinking down to the floor, leaving only two figures remaining — Prospero, betrayed by his philosophy… and his sole remaining companion, Death. The movie concludes with the Red Death meeting his Brother Deaths, who have been stalking the world that night, to share their tales and then resume their “eternity of wandering.”

Though the days are gone when I had the stamina — or desire — to watch The Masque of the Red Death for five nights in a row, it’s still a movie that repays many viewings. It’s so solidly written, acted, and directed that there’s always fresh pleasure to be had out of watching it.

With this, our exploration of the Corman Range is finished for today – finished but far from complete. There remain such challenging peaks as X – The Man With the X-Ray Eyes and The Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre and such lush, inviting foothills as Attack of the Crab Monsters and The Day the World Ended. However, we should descend to base camp and renew our strength before attempting anything further. But before bidding farewell to Roger Corman, I commend those who have a further interest in this amazing filmmaker and his career to two resources.

With this, our exploration of the Corman Range is finished for today – finished but far from complete. There remain such challenging peaks as X – The Man With the X-Ray Eyes and The Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre and such lush, inviting foothills as Attack of the Crab Monsters and The Day the World Ended. However, we should descend to base camp and renew our strength before attempting anything further. But before bidding farewell to Roger Corman, I commend those who have a further interest in this amazing filmmaker and his career to two resources.

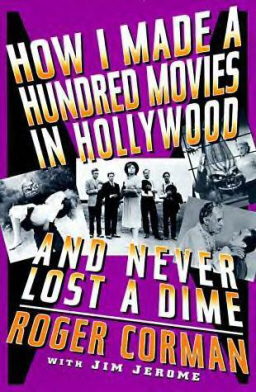

The first is Corman’s 1990 autobiography (written with Jim Jerome), How I Made a Hundred Movies In Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime. It’s a good-natured read that’s full of self-deprecating anecdotes, and Corman gives over a large part of the book to the people that he’s worked with over the years, so they can tell their own hilarious tales of Corman “economy.”

The book is currently in print in paperback from Da Capo Press. (A new book on Corman came out only last year: Crab Monsters, Teenage Cavemen, and Candy Stripe Nurses: Roger Corman: King of the B Movie by Chris Nashawaty. I’ve not seen a copy, but with a title like that, it’s halfway home… )

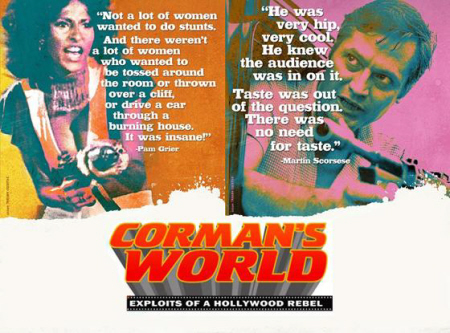

The other source is a documentary movie, 2011’s Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel, directed by Alex Stapleton.

Plenty of film clips and interviews with Corman himself and, again, many of his co-workers through the decades — among them, John Sayles, Martin Scorsese, David Carradine, Bruce Dern, Jonathan Demme, Ron Howard, Robert DeNiro, Peter Bogdonavitch, Peter Fonda, and, of course, Jack Nicholson — make the movie a delight.

(One of the most amazing — and startling — things I’ve ever seen on film is Jack Nicholson, Mr. Laid-Back Cool himself, breaking down in tears as he speaks of his love and respect for Roger Corman, and his gratitude for the support Corman gave him when he was a struggling actor.)

In 2010, Roger Corman won a well deserved and long delayed honorary Oscar for “his rich engendering of films and filmmakers.” Damn right. Me… I just love his movies. Roger is eighty eight years old now, and It’s hard for me to imagine a world without him.

Fortunately I don’t think I have to worry about it for a while, because as long as there remains a single nickel to be squeezed out of a budget, Roger Corman will be on the case. I can’t tell you he never made a bad movie, but I love them all anyway, and hey… he never lost a dime.

I’m responding to your remarks about television channels, not about Corman. I was a kid in Coos Bay, Oregon, in the second half of the 1960s. We didn’t have cable, so that meant: one channel! It was an NBC affiliate, so we got The Man from UNCLE and Star Trek — plenty to keep this kid, at least, in a tizzy.

I think the DC area had an affiliate of your Channel 5 back in the 1980s. They had the same budget-driven devotion to classic movies, bad and good. On weekdays, they ran vintage cartoons, right back to the 1930s — Merrie Melodies, Woody Woodpecker, the Bugs Bunny cartoons with the pop culture references so old they needed footnotes before the advent of the 1970s. And best of all, every New Year’s Eve, they ran a Marx Brothers marathon, the entire output of that screwball family. It was intended as something babysitters could put on in front of kids whose parents were out at parties, but my parents were Groucho Marxists, so we got together with similarly inclined families and rang in the New Year with sparkling cider and a chorus of “Hail, hail Freedonia, land of the brave and free!”

Sarah, that’s got to be the best New Year’s Eve idea I’ve ever heard!

I have ‘The Raven’ somewhere on DVD. It’s excellent (although Jack Nicholson’s star quality is less than evident). Corman had a studio here in Ireland for years – the government was offering tax incentives to companies that set up in Irish-speaking areas, so he set up shop in the west. Stories about his ingenuity when it came to saving a buck were legion – e.g. building two sets, side-by-side for a car crash scene – actually two separate car crash scenes, in two separate films; the car crashes into a shop-window in one but bursts out of a brick wall in another. How true this is (and if it was, whether it happened in Ireland) I couldn’t say.

The Raven is another favorite, though it’s carried more by good nature and high spirits than by great comedy writing (not Richard Matheson’s forte). I always look forward to the Price/Karloff duel of magic at the end.