The Sorcery of Storytelling: The “Imaginary Worlds” of Darrell Schweitzer

Special Black Gate Feature

by John R. Fultz

All rights reserved. Copyright 2006 by New Epoch Press.

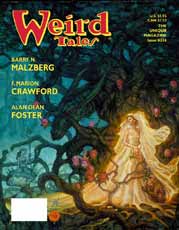

When speaking of the world’s greatest writers of fantasy fiction, there is one name that continues to surface among the true experts, if not on the lips of the general public: Darrell Schweitzer. Most widely known as a long-time editor of the legendary Weird Tales magazine (along with George Scithers and John Betancourt), Schweitzer is a prolific fantasist whose mythopoeic stories and novels often challenge his readers’ perceptions of reality while exploring the darker side of heroism…and sorcery. He has consistently broken new ground in the fields of heroic fantasy, weird fiction, dark fantasy, and horror. Yet the man that Mike Ashley’s Mammoth Book of Sorcerer’s Tales calls “…today’s supreme stylist…” consistently defies being labeled with any particular genre. Schweitzer’s work truly stands in a class by itself.

When speaking of the world’s greatest writers of fantasy fiction, there is one name that continues to surface among the true experts, if not on the lips of the general public: Darrell Schweitzer. Most widely known as a long-time editor of the legendary Weird Tales magazine (along with George Scithers and John Betancourt), Schweitzer is a prolific fantasist whose mythopoeic stories and novels often challenge his readers’ perceptions of reality while exploring the darker side of heroism…and sorcery. He has consistently broken new ground in the fields of heroic fantasy, weird fiction, dark fantasy, and horror. Yet the man that Mike Ashley’s Mammoth Book of Sorcerer’s Tales calls “…today’s supreme stylist…” consistently defies being labeled with any particular genre. Schweitzer’s work truly stands in a class by itself.

As the author of over three hundred published short stories and three critically-acclaimed novels, Schweitzer’s individual work was nominated three times for the World Fantasy Award, and he received the award once as part of the editorial trio of Weird Tales. While successful as an essayist and literary critic, it is his weirdly brilliant fiction that has cemented him as one of the elite talents in the world of fantasy. Yet many of today’s fantasy fans have yet to discover Schweitzer’s work, perhaps because it lies well out of the mainstream — even his epic fantasies contain dark themes fueled by his fascination with the elements of horror. As author Tanith Lee puts it: “Not only is [Schweitzer] skilled in the exotic use of the best trappings of Fantasy, he employs a disquieting awareness of the dark nooks of the mind and soul…”

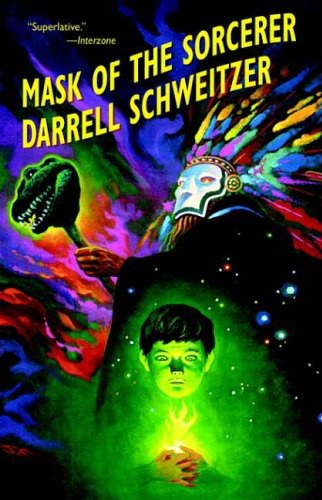

Mask of the Sorcerer, the greatest of his three novels, chronicles the rise to power of Sekenre, an immortal sorcerer trapped in the ageless body of a child. But the growth of Sekenre’s cosmic power isn’t a clever jaunt through lighthearted, Harry Potter-style adventures. Rather, it is a torturous journey through the realm of Death itself, a centuries-long baptism in pain, self-recrimination, abysmal suffering, and hellish confrontations with a legion of diabolical sorcerers who have surrendered their humanity in exchange for power. The underlying question of the novel (which is also a metaphorical exploration of a dysfunctional child-father relationship) becomes: Can Sekenre master the sorcery that threatens to devour him and still retain the qualities that keep him essentially human? Or will he end up as simply another monster trapped by the undying curse of sorcery itself?

Mask of the Sorcerer, the greatest of his three novels, chronicles the rise to power of Sekenre, an immortal sorcerer trapped in the ageless body of a child. But the growth of Sekenre’s cosmic power isn’t a clever jaunt through lighthearted, Harry Potter-style adventures. Rather, it is a torturous journey through the realm of Death itself, a centuries-long baptism in pain, self-recrimination, abysmal suffering, and hellish confrontations with a legion of diabolical sorcerers who have surrendered their humanity in exchange for power. The underlying question of the novel (which is also a metaphorical exploration of a dysfunctional child-father relationship) becomes: Can Sekenre master the sorcery that threatens to devour him and still retain the qualities that keep him essentially human? Or will he end up as simply another monster trapped by the undying curse of sorcery itself?

Mask originally began as a novella called “To Become a Sorcerer,” (nominated for a World Fantasy Award), and grew into an epic novel of staggering emotional impact, soul-wrenching horror, and transcendental sorcery. “The fear is chilling, the excitement intense,” said Morgan Llywelyn of the novel. “But mostly Mask of the Sorcerer is about magic. True magic. Magic that rings in the bones and the soul, magic that very few contemporary writers can understand or create. Darrell Schweitzer is a sorcerer, and his knowledge of magic is awesome.”

Upon completing Mask, Schweitzer continued to explore the immortal existence of Sekenre in a series of twelve stories that grew in mystical complexity, surreal depictions of sorcery, and celestial scope. Sekenre: The Book of the Sorcerer is a sequel of sorts to Mask, yet it plays a double role as the book that Sekenre himself writes during the course of his arcane adventures, wherein he often steps outside of space and time to chronicle events. Mask and Sekenre are two must-reads for any lover of fantasy fiction. But don’t expect happy elves and wand-waving wizards: these books explore the darkness that lies behind a mythical reality, even as they investigate the enduring nature of humanity in the face of otherworldly forces.

Schweitzer’s two other novels, The White Isle and The Shattered Goddess, written much earlier in his career, are no less unique and brilliant. The White Isle is a poetic novel of heroic fantasy, full of beautiful and terrible imagery, as a young prince attempts to rescue his beloved from the God of Death himself. The Shattered Goddess takes place millions of years in the future, when the Goddess of Earth has perished and the remnant of her immense power “flickers over her colossal corpse like deadly lightning.” In this nightmarish world, the young hero sets out to discover his true identity during what may be the final epoch of human history. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy comments: “The novel has immense power in its climax.”

Another of Schweitzer’s most important major works is not quite a novel, but a collection of Arthurian-style stories chronicling the bizarre quest of the knight known as Sir Julian the Apostate. We Are All Legends is a thrilling twelve-story cycle that follows Sir Julian’s quest for meaning and salvation, and his journey into “the realms of nightmare, where monsters abound, the Devil may (or may not) rule, all is deception, and sorcerers and lamias may (or may not) know the way to Heaven.” Schweitzer has since returned to the theme of the “questing knight” in many separate stories, but We Are All Legends offers an extended, phantasmagoric odyssey composed of dark, beatific pieces.

Another of Schweitzer’s most important major works is not quite a novel, but a collection of Arthurian-style stories chronicling the bizarre quest of the knight known as Sir Julian the Apostate. We Are All Legends is a thrilling twelve-story cycle that follows Sir Julian’s quest for meaning and salvation, and his journey into “the realms of nightmare, where monsters abound, the Devil may (or may not) rule, all is deception, and sorcerers and lamias may (or may not) know the way to Heaven.” Schweitzer has since returned to the theme of the “questing knight” in many separate stories, but We Are All Legends offers an extended, phantasmagoric odyssey composed of dark, beatific pieces.

As brilliant as his novels are, Schweitzer’s true milieu is the short story. After three hundred published tales, he’s still cranking out fresh fantasy gems such as “At the Top of the Black Stairs,” (which appeared recently in Realms of Fantasy) and weird horrors such as “The Most Beautiful Dead Woman in the World” (which originally ran in Interzone and was recently reprinted in Weird Tales). Luckily for any fan of great short fiction, his vast body of stories has been assembled into several affordable collections including: Nightscapes, Refugees from an Imaginary Country, Tom O’Bedlam’s Night Out, The Great World and the Small, and the truly strange Necromancies and Netherworlds (featuring stories co-written with artist Jason Van Hollander). Readers will find these books endlessly entertaining, while writers will find one example after another of perfectly written short fiction, excursions into an imagination that apparently knows no bounds. Also an accomplished poet, Schweitzer’s Groping Toward the Light collects much of his dark and evocative poetry, often inspired by supernatural themes.

Black Gate recently interviewed Darrell Schweitzer about his expanding body of work, his future plans, his storied career at Weird Tales, and other important topics in the world of fantasy fiction.

When did you start writing short stories, and how long did you write and publish them before you wrote your first novel, The White Isle?

I began writing when I was fourteen. When I was nineteen, I had produced a story which would later be published professionally (“The Story of Obbok”). I had sold about twenty-five stories, including a ten thousand-word version of The White Isle, before I wrote the book. But if you go and look at the novelette (in Weirdbook #9) you can see it greatly needs development. The whole second half is little more than an epilogue. This was not a successful novelette. It needed to be a novel all along, but at age twenty or so I was not skilled enough to write it. By the time I was twenty-three (in 1975), I was.

Was the publishing industry a different beast back then?

I think the paperback houses were a little more willing to read an unsolicited manuscript than they are today. There was more of a sense that you could just publish a book and it would do about as well as any other book in that category. Today there is a much more intense insistence that the author be able to do it again, and produce a predictable sequence of books which can be used to build up an audience to the best-seller level. Then (about 1975) there was a lot more freedom, frankly because expectations were lower. Good books could be published, and as long as they made a modest profit this was acceptable. Thus, things like Avram Davidson short-story collections or R. A. Lafferty novels, or something as eccentric as David Bunch’s Moderan could be published in mass-market paperback. That would be unthinkable today.

The short story market was different too, mostly in the sense that most professionals did not understand what the small-press was. The prevailing old-timer’s view was that anything not distributed on a newsstand was a fanzine, i.e. completely amateur and unworthy of notice. They didn’t understand what Whispers, Weirdbook, Fantasy Tales, and the like were for many years. It was the anthologists who led the way. You couldn’t help but notice that more than half of the contents from, say, The Year’s Best Horror (the DAW series, then edited by Gerald W. Page) were taken from the “amateur” press. There was virtually no horror/fantasy market at the “professional” level. Something like Realms of Fantasy was an impossible dream.

You’ve written hundreds of short stories and only a few novels — what is it about the short story format that so appeals to you as a writer?

You’ve written hundreds of short stories and only a few novels — what is it about the short story format that so appeals to you as a writer?

Limited attention span? I honestly think I didn’t learn to write novels more readily because publishers were never deeply interested. To this day I have only had mass-market paperback publication in England, briefly, for The Mask of the Sorcerer and The Shattered Goddess. The result is that my novels only get written when they really demand to. If I had been strongly encouraged in the early ‘80s, with publishers beating a path to my doorstep and waving lots of money, I might have developed differently. Or not.

The other answer is that the short-story form has an aesthetic of its own, in many ways akin to poetry, in that you grasp the overall structure of a story much more readily. Look at something like “The Sorcerer Evoragdou” (in Refugees from an Imaginary Country). This is a fantasy time-travel story. Mysterious boy, age twelve, shows up in the village. He seems quite mad. Shortly thereafter our hero, age ten, sees the house of the Sorcerer Evoragdou (which is ever changing and unstuck in time) and the sorcerer appears on a balcony and calls out to him. This gets him into a lot of trouble, but he still manages to grow up. When he is an adult, his own son disappears into the house of the sorcerer. The hero goes in after him. In the process he becomes the sorcerer, and so the sorcerer on the balcony calling out to his ten-year-old self is his older self speaking to his younger self. Meanwhile the missing son (aged twelve) steps out a door into the past and is the mad boy who showed up during his own father’s childhood.

Now you could blow this up to a hundred thousand-word novel, but I don’t think that structure — the aesthetic appeal of the relationship between the parts — would be nearly as obvious if you did.

One of the traits that sets your fantasy work apart from other writers is the “dark” undercurrent runs through even your epic fantasies such as The White Isle, The Shattered Goddess, and The Mask of the Sorcerer, three classics of the dark fantasy sub-genre. What is your definition of “dark fantasy,” and do you think the term applies to your work?

I am not sure the term “dark fantasy” is at all useful. It became current during the ‘90s when the commercial horror field had collapsed so badly that the survivors had to come up with new labels so they could pretend they were not horror writers. The non-fantastic ones became “dark suspense” writers and the ones who wrote supernatural stories became “dark fantasy.” It’s sort of like pretending a “sanitary engineer” is different from a garbage collector.

All three of these books are imaginary-world fantasies. They are dark or horrific in tone rather than light and funny, admittedly. They have more in common with Clark Ashton Smith than Thorne Smith, let us say. The White Isle should be “sword-and-sorcery” by anybody’s definition, “heroic fantasy” by most. The Shattered Goddess has a lot in common with [Jack Vance’s] The Dying Earth or Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun, save that it is clearly supernatural fantasy, not a story of far-future science perceived as magic.

The Mask of the Sorcerer is, well, whatever Clark Ashton Smith’s stories about eldritch sorcerers of Zothique are, save that it has a lot more personal detail and a very different technique. The hero is the sorcerer. At one point a couple of barbarian swordspersons come in through the window, beat him up, and try to extract his dead father’s dread secret. They last about a page before they come to a hideous doom. The hero actually has a sword, which figures in the novel in small but important ways. He inherited it from his father, who was an anti-sorcerous Knight Inquisitor as a young man, when he was in denial about what he really was. The world-building scheme bears some relationship to Robert E. Howard, in that the setting consists of various countries which have analogues in our world. Riverland is an Egypt analogue. Across the Crescent Sea are the lands of the barbarians, who are pseudo-European.

The Mask of the Sorcerer is, well, whatever Clark Ashton Smith’s stories about eldritch sorcerers of Zothique are, save that it has a lot more personal detail and a very different technique. The hero is the sorcerer. At one point a couple of barbarian swordspersons come in through the window, beat him up, and try to extract his dead father’s dread secret. They last about a page before they come to a hideous doom. The hero actually has a sword, which figures in the novel in small but important ways. He inherited it from his father, who was an anti-sorcerous Knight Inquisitor as a young man, when he was in denial about what he really was. The world-building scheme bears some relationship to Robert E. Howard, in that the setting consists of various countries which have analogues in our world. Riverland is an Egypt analogue. Across the Crescent Sea are the lands of the barbarians, who are pseudo-European.

Terms are slippery things. “Sword-and-sorcery” itself is difficult to define. Is The Mask of the Sorcerer sword-and-sorcery? It has all the elements, only the Sorcery dial is turned up to maximum volume, and the Sword dial is down to a whisper.

In your estimation what are the elements that make truly great fantasy fiction? Truly great horror? Is “weird fiction” more than simply a co-mingling of these two genres?

The point of much fantasy is to deal with mythic elements directly, rather than through symbol and metaphor only. You could, for example, write a story about someone who “sells his soul” and makes a “Faustian bargain,” i.e. he sacrifices his personal integrity in an irretrievable manner for some dubious goal-say, success in the Mafia, or in Hollywood, or in politics. It needn’t have any fantastic content, and the Faust symbolism would resonate. But the fantasist’s approach is to bring the actual demon on stage and deal with the material directly.

I have long argued (see “Horror Beyond New Jersey” in Windows of the Imagination) that horror does not have to be in a contemporary or even historical setting. I will go along with Douglas Winter’s definition that horror is an emotion. Okay, The Mask of the Sorcerer is a horror novel, set in a fantasized ancient Egypt with crocodile-headed gods and a literal (not symbolic) journey into the Land of the Dead. Its actual horror comes from the character’s fear of loss of self. His great fear is that he will cease to be who he is (or wants to be) and will instead become a monster.

I am not sure that the term “weird fiction” is all that useful. Lovecraft used it to mean fiction which deals with unreality, departures from the possible and knowable. Isn’t that what any sort of supernatural fantasy does?

Looking back on your long-form works (The White Isle, The Shattered Goddess, The Mask of the Sorcerer), which of those novels is your favorite and why?

I would have to hold out for The Mask of the Sorcerer. It is the richest and the best developed, with the most intriguing protagonist. I’m due for a fourth novel. When it comes, hopefully, it will be a step beyond Mask, even as that is a step beyond Goddess, and Goddess is a step beyond The White Isle.

You’ve written a long string of tales involving variations on the theme of the “knightly quest,” many of which were collected in We Are All Legends to tell the unforgettable legend of Sir Julian the Apostate, while others appear in Nightscapes, etc. What source materials inspired your fascination with knights and the transcendental quest motif?

You’ve written a long string of tales involving variations on the theme of the “knightly quest,” many of which were collected in We Are All Legends to tell the unforgettable legend of Sir Julian the Apostate, while others appear in Nightscapes, etc. What source materials inspired your fascination with knights and the transcendental quest motif?

Maybe it’s because I have a twelfth-century mind. The quest motif is an ideal allegorical form for stories about becoming who we are, for discovering what life and the universe mean. All the big themes. A very great early influence on me is the Ingmar Bergman film The Seventh Seal, which is such a quest into the nature of self and of existence.

I return again and again to the theme of the Hero, most recently in “The Hero Spoke” in Realms of Fantasy. The great paradox here is that the hero, in order to be heroic, must also be in some sense terrible. Achilles is a great hero, but as one of the characters in the movie Troy remarked, he was “born to end men’s lives.” A natural killer, but great at the same time. This is why what the hero finds at the end of the heroic quest (which is the quest to shape and perfect yourself) is often bitter.

I just finished watching one of those hundred-part Korean historical serials on TV, The Immortal Yi Shoo Shin. Great stuff. It is about the creation of the perfect hero. (The real Yi Soon Shin was a great Korean naval commander of the late 16th century, a natural military genius like Napoleon or Horatio Nelson.) He won twenty-three battles against the Japanese who had invaded and ravaged his country, sometimes against incredible odds, as when he defeated three hundred ships with only twelve. He was a man of great vision, who saw the need to equalize social differences so all classes would feel they had a stake in the country’s defense. He was also open to technical innovation at a time of otherwise hopeless conservatism. He produced the world’s first ironclad. But what makes him a hero is the way the series ends.

In reality, Yi Soon Shin, like Nelson, was hit by a bullet at the moment of his greatest victory. From this the TV writers fashioned a moment of sublime tragedy. Admiral Yi has been on the outs with his king, who is a paranoid incompetent. At one point Yi was relieved of his post, tortured, and busted to private, and he bore this all without complaint because he never lost sight of his goal, which was to defend the country, rather than to advance his career. His successor lost the entire fleet in a single battle, so the King had to reinstate Yi anyway. At the end, though, the king has ordered Yi arrested once more. He wants to let the Japanese (who are pretty tired of this war) just leave. Yi realizes that the enemy is going to go back to Japan, recover, and come back in a year or so. The war must be ended decisively now. So when the king’s envoys arrive, he locks them up, which has put him irretrievably over the line of disobedience. He gathers his forces and goes into one last battle, knowing he must win everything in one shot, and that there can be no place for him in the post-war peace, since he has become, in effect, too great. Political factions would form around him. He is vastly more popular than the king. He will never be able to retire.

Many generals in this circumstance throughout history have changed sides. His other choices would be to either submit and let the king execute him afterwards, or to become a rebel and traitor, march on the capital, and depose the king. But this would start a civil war and undermine everything he has done to bring peace to the country.

Many generals in this circumstance throughout history have changed sides. His other choices would be to either submit and let the king execute him afterwards, or to become a rebel and traitor, march on the capital, and depose the king. But this would start a civil war and undermine everything he has done to bring peace to the country.

So what he does is politely lock up the king’s envoys, go into battle, win, and seek death on the battlefield. He deliberately exposes himself in such a way that, at the moment of victory, he is killed. He has chosen this path because it is for the best.

So let’s say that right now I am intrigued by the inherent tragedy of the heroic ideal. A hero who just conquers everything and lives happily ever after isn’t very interesting. But the tragic hero is. There must be a cost for greatness.

You created one of the most interesting and bizarre characters in fantasy literature, the insane mystic Tom O’Bedlam, publishing many tales of his surreal adventures. Was this character a reaction to the typical strong-jawed fantasy hero, or does he have more complex origins?

He has his origins in the section of “Mad Songs” in Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (eighteenth century). Tom O’Bedlam is a figure out of English folklore. He is mentioned in King Lear (the “Tom’s a-cold” bit on the heath). At one time the less dangerous lunatics were let out to beg and called “Tom O’Bedlams.” Into the eighteenth century there was a law against “false Tom O’Bedlams,” i.e. ordinary beggars who discovered that impersonating a lunatic was lucrative.

The origin of my Tom O’Bedlam is “Tom O’Bedlam’s Song” (which is probably Elizabethan), particularly the last verse:

By a knight of ghosts and shadows

I summoned am to tourney,

five miles beyond the wide world’s end,

methinks it is no journey!

Questing again.

Perhaps your most beloved character creation thus far is Sekenre, the immortal sorcerer trapped in the ageless body of a child. Throughout the course of a novel (The Mask of the Sorcerer) and a dozen succeeding stories (collected recently in Sekenre: The Book of the Sorcerer), you have explored the transcendental and metaphysical aspects of sorcery itself, often taking your readers on mental journeys that defy description and challenge their perceptions of reality. How do you approach creating such unique and original effects when depicting sorcery in your writing?

Perhaps your most beloved character creation thus far is Sekenre, the immortal sorcerer trapped in the ageless body of a child. Throughout the course of a novel (The Mask of the Sorcerer) and a dozen succeeding stories (collected recently in Sekenre: The Book of the Sorcerer), you have explored the transcendental and metaphysical aspects of sorcery itself, often taking your readers on mental journeys that defy description and challenge their perceptions of reality. How do you approach creating such unique and original effects when depicting sorcery in your writing?

I suppose the really original idea [in Mask] is that sorcery is a contagion. You become a sorcerer by various means, most readily by killing one. You cannot escape what you have become once this has happened. Sekenre would like very much to get the trouble “over with” and go back to being an ordinary boy, but it isn’t going to happen. Of course, life itself is like this. We change into something else. A kid might take a Peter Pan-type stand and say “I won’t grow up,” but he will anyway. The irony is that Sekenre physically does not grow up, which only isolates him more and more from the humanity around him.

Sorcery itself is depicted [in the novel] as a power of darkness, something from the evil side of a dualistic universe. Sekenre’s great struggle then is to remain at least morally neutral, even though he will never be truly human again, and he will never be a saint. (Sorcerers cannot see the gods, but they do see the Shadow Titans.)

Your “Riverland” stories, which gave birth to Sekenre and his universe, have been published in various magazines and are scattered across your collections. How likely is it that you will publish a “Riverland” book that collects all the non-Sekenre tales set in that universe?

If someone were to reshuffle my Complete Works someday this might happen, but I have always had to make a choice between putting all the stories of one type into one book or mixing them up. I have chosen to mix them up, not only because many of the series are still continuing. (So I do a complete Riverland and then write another story. Then what?) Also, this avoids too much repetition. A collection of my Arthurian stories might be a little monotonous, because most of them are about marginal knights on quests to discover the awful truth at the end of heroism. I could call such a book The Dark Knight of the Soul, but would have the decency not to.

Personally, I think a collection of your Arthurian stories would be fascinating. However, as a follow-up to the “Riverland” question: Do you plan to re-visit the Riverland universe in any future stories or novels?

I haven’t stopped, although I have moved to the fringes. The most recent story I have written, “Thousand Year Warrior,” takes place somewhere beyond Sekenre’s horizon, but in the same universe. I haven’t visited Riverland itself and the City of the Delta in a while, admittedly.

Let’s talk a bit about inspiration: What inspires you to sit down and write, say, a horror story, as opposed to the inspiration for writing a fantasy story? Is it a matter of mood, or do you respond to different stimuli and write without regard to what genre you’re working in?

L. Sprague de Camp used to say that the secret of writing is “the application of the seat of the pants to the seat of the chair,” and there is much practical wisdom in that. I can’t write when I have nothing to say, though. I am not one of these people who stares at a blank screen (or before that, a piece of paper) until Something Comes. I usually have some images, some of the language in mind, and have some grasp of the overall structure of the story. To use the analogy to poetry again, so this is going to be a sonnet. I don’t know all the lines yet, but it definitely needs to be a sonnet. That is when I start writing.

I mix horror and fantasy (as in the Riverland stories) so much that there can be no meaningful distinction between what causes me to write a modern-scene story (which would be classed as horror) or a non-modern/non-real scene story (which would be classed as fantasy). This was the point of “Horror Beyond New Jersey.” Suppose you have a story about a “dead” man who comes back to his old town and house, but no one can see him, as if he is invisible. He crawls into bed with his wife, and he hears her moaning. He looks over and realizes she is biting her hand to prevent herself from screaming. She knows he’s there.

Pretty horrific scenario, right? Set in it contemporary New Jersey and it is undeniably a horror story. But I set it in the fringes of Riverland, in what might loosely be described as Hellenistic Peru, in “Going to the Mountain.” Is it still a horror story? I think so. Clark Ashton Smith could set genuine horror stories on Mars. I can set one in Riverland.

These categories are ultimately marketing tools. Horror is what is published as horror. Fantasy is what is published as fantasy. It’s all about labels and which shelf in the bookstore a book is displayed on. Aesthetically, the distinction is not particularly meaningful.

How does your writing process work? Do you spend a lot of time planning and musing before you let the ink fly, or do you sometimes leap right in with a vague idea of where you’re going? How do you approach problem-solving when it comes to making an ephemeral idea take concrete shape via words and paper?

How does your writing process work? Do you spend a lot of time planning and musing before you let the ink fly, or do you sometimes leap right in with a vague idea of where you’re going? How do you approach problem-solving when it comes to making an ephemeral idea take concrete shape via words and paper?

I am not an outliner. For years after I had a computer, I still wrote the first draft on a typewriter, then took that to the computer, because I needed the process of retelling the story (rather than just patching a line here and there) to get it right. It is the difference between saying, “Hey, remember that joke I told the other night? The punch line should have been ___” and actually retelling the joke, adjusting the details and pacing and language until you get to the revised punch line.

I have since learned to compose more at the computer, though if a story is going badly, I may still print out the draft, then keep that on hand when (a couple days later) I may start a new file and begin again rather than try to patch the old version. This may mean I retype some passages several times, but I think I need that extra immersion in the story.

I wrote poetry longhand, in notebooks, at least a first draft, often several, because poetry is much more of a matter of moving up and down the page in a non-linear fashion, changing something in line four so line twenty-seven works. I then take this to the computer and usually what I type in is somewhat or even substantially different from what is in the notebook.

Nonfiction I compose easily on a computer. Computers were invented for book reviewers who are assigned to write a review of precisely 220 words for Publishers Weekly (something I do). You do a rough version, then cut, rephrase, cut some more, until it fits.

I first discovered your fiction in the pages of Weird Tales when it was revived in the late ‘80s-and you were already an editor for the magazine at that time. (Specifically, when I read “Mysteries of the Faceless King” in the Spring ‘88 issue of WT, I became an instant Schweitzer fan. This amazing story has since been collected in Refugees from an Imaginary Country.) How did you come to be involved with The Magazine That Wouldn’t Die, and what have been the most rewarding experiences of your nearly twenty years as a Weird Tales editor?

I first discovered your fiction in the pages of Weird Tales when it was revived in the late ‘80s-and you were already an editor for the magazine at that time. (Specifically, when I read “Mysteries of the Faceless King” in the Spring ‘88 issue of WT, I became an instant Schweitzer fan. This amazing story has since been collected in Refugees from an Imaginary Country.) How did you come to be involved with The Magazine That Wouldn’t Die, and what have been the most rewarding experiences of your nearly twenty years as a Weird Tales editor?

Your discovering me there is a good deal of the satisfaction. There’s been a lot of controversy about whether an editor should publish in his own magazine, but I take my cue from Frederik Pohl of Galaxy and Michael Moorcock of New Worlds, and a very long list others. It was never entirely my magazine anyway, even during the brief period around 1990 when I was listed as sole editor. We had merely promoted George Scithers to “publisher,” but the day-to-day operation of the magazine didn’t change much. Stories were bought by a best-of-three method, divided originally between George Scithers, John Betancourt, and myself, and when John left for a time, between George, myself, and the “Editorial Horde” who counted as one vote. For a story of mine to be bought, I was not allowed to vote and everyone else had to be unanimous.

So I don’t regret doing it, and I am glad you discovered me that way, though it is presently against company policy for me to publish fiction in the magazine, now that John Betancourt is sole publisher and boss (i.e. it’s his money and his magazine) and is entirely within his rights to have set this policy. There is a precedent for that too. Traditionally, editors of Analog do not publish fiction in Analog. The publishing industry has always worked both ways.

From an entirely selfish point of view, the most rewarding thing about Weird Tales for me has been using it to get my very best fiction in front of precisely the right audience-but that is selfish. The other rewards are simply that we have re-created Weird Tales and sustained it for, now, nineteen years. (We had the Spring 1988 issue out for the World Fantasy Con in October of 1987.) There was a time when we thought we’d get rich doing this, but that soon passed. It was often done at considerable personal expense, but I think that in matters of art, end justifies means. The issues we have done so far speak for themselves. We have discovered and developed new writers, including somebody named John R. Fultz. We have sustained old writers, providing Charles Harness with a steady market in the last (and quite creative) phase of his life and career. We have made the field that much larger. We have done our best to keep our particular kind of horror-fantasy mix alive for two decades now. Jason Van Hollander says that the issues of Weird Tales I have co-edited should be placed in my death-boat to justify me before the gods. So they shall.

As for how I became editor, well, when George ceased to be editor of Amazing, we had this leftover editorial team, and all we needed was a magazine. John Betancourt was the one with the real imagination, energy, and drive-and the one who raised the capital-to make this move beyond something we’d “sure like to do” to something we were doing. He deserves the credit for that.

If you want to see something I edited alone, look for The Vampire Secret History from DAW next January. This is one of those books which is edited by Martin H. Greenberg and someone else. The someone else (me this time) acquires all the stories. Greenberg sells the book, handles all the money, negotiates the contract etc., but I chose the stories. There’s a Harry Turtledove story in it I’m particularly proud of. It’s both horrific and very funny, the real Inside Dope on the Vatican, something to make The Da Vinci Code seem very tame indeed. The premise of the book is that certain things in history make a lot more sense with a vampire here and there. What exactly did Teddy Roosevelt do with that big stick? (Mike Resnick answers that one.) Actually the book will read a lot like Weird Tales because I immediately turned to the Weird Tales regulars for stories: Tanith Lee, Carrie Vaughn, Sarah Hoyt, Ian Watson, Brian Stableford, etc., all writers I knew from Weird Tales experience would be reliable.

Can you name some authors who you believe are today’s brightest fantasy novelists, and tell us what makes their work so important?

Can you name some authors who you believe are today’s brightest fantasy novelists, and tell us what makes their work so important?

This is a big question. I am not sure anybody knows, because there is too much to read and no one can cover it all. Gene Wolfe is certainly a very great writer, for sheer brilliance of his craftsmanship and the subtle depth of his thought. He is one of the very few writers with whom, if you didn’t understand the story the first time, you really should go back and read it again, because you have missed something. Tanith Lee strikes me as the perfect Weird Tales writer, which is probably why WT has published more by her than anyone else. Her work is poetic, sensual, scary, imaginative, erotic if it needs to be. She’s got everything. Not all of his novels satisfy me but Jonathan Carroll is perhaps the finest writer of contemporary-scene fantasy. His first novel, The Land of Laughs, is still a great work. I also much admire Thomas Ligotti. I wish he would write more. He is a very dream-like writer. When you are done with one of his stories it is like awakening from a very vivid dream. You may not understand or even remember all the details, but the feeling you had stays with you. I think I have re-read his “Nethescurial” four or five times by now, and I keep finding more in it.

This shows you how editing is a personal matter. The Weird Tales aesthetic, as I see it, is something that falls within the range of those four writers. Of course you realize that I am only one-third of the editorial team these days, so I cannot claim to be officially speaking for the magazine right now, or for John or George.

What would you like to see happen in the fields of fantasy and horror in the next five to ten years? What needs to happen to keep the genres healthy?

We need more magazines. In book publishing, the smaller independent publishers must break the distribution barrier and get into the chain bookstores in a big way. New York publishing is open to less and less. I mentioned this before. Much of what made the late ‘60s such a creative period would be impossible today. Can you imagine Lafferty’s Nine Hundred Grandmothers in mass-market paperback today? If a new Avram Davidson or a Lafferty came along today, he’d never get into the big houses at all. If he were lucky, he’d get published by Small Beer Press (Kelly Link’s notably successful and prestigious small-press imprint). Many books today never get into mass market at all. They appear only in hardcover or trade paperback, which may mean the total print run for a non-bestseller could be under ten thousand copies. The reason you see so many trade paperbacks nowadays is that a trade paperback is like a cheap hardcover (the binding is cheaper) and it is possible to make a profit with a book selling two to three thousand copies in trade paperback.

Forty years ago, you could assume anything in SF/fantasy would sell more like thirty to fifty thousand copies in mass-market paperback without even trying. Just slap the right kind of cover on it and it would sell this acceptable minimum. Well, maybe the ceiling on genre fiction has come off, and today you get an Anne McCaffrey or a Stephen King who can sell millions of copies, but we have also lost the floor, which protected us. Now the major publishers are only interested in writers who have the potential to be the next McCaffrey or King, not the interesting mid-list writers who are worth publishing for what they are, even if they never will sell a million copies — the Davidsons and Laffertys. We have lost our innocence. Once it was demonstrated that SF/fantasy/horror could go to the top of the bestseller lists, anything that doesn’t is now viewed as a failure by those faceless, impersonal Suits who control corporate publishing.

The U.S.A. has a population of three hundred million. Two thousand copies is not a lot. We have a reading public the size of Luxemborg’s. What any genre needs to stay healthy is more readers and a means of reaching them.

When you’re not engaged in writing or editing, what do you find yourself doing? Do you work in any other capacity than writer/editor?

You mean there is time when I am not writing and editing…? Uh, seriously, I do not have a day job, but I derive a good deal of my income (and spend a good deal of time) “liquidating assets” (as we call it for tax purposes) on eBay. Look me up as darrellschweitzer_pa. I usually have about forty auctions running.

I have hobbies, more than I have time for. I could get seriously into amateur astronomy if I had more time. (I own a pretty good telescope, but now I live in a city.) I once learned how to play chess, but I haven’t done it in years. I have a stamp collection which has been growing, unsorted, in a box for many years now, in hopes that I will one day “get to it” and put it all in order. (When you work with magazines all this time, you see a lot of interesting stamps on the incoming mail.) I am a fairly serious collector of ancient coins and a middling-level expert in Roman and Byzantine numismatics. A couple years ago I built a model pirate ship in painstaking detail, even inventing a method (which involved cutting the tip of a toothpick with a razor to make a “brush”) to paint all the little gold squiggly trim, just to see if I could still do it. (I still have my Aurora Model Kit Dracula that I built when I was a kid, doubtless a priceless collector’s item now.) My wife, who observes the clutter with chagrin, notes that I am not very good at letting go of things. I am a pulp magazine and book collector, and something of an expert in doctoring ailing pulp magazines. I have designed t-shirts. If you see someone walking around at a convention in a T-shirt that says “Tibetan Olympic Corpse-Wrestling Team” or “Byzantine Stooges,” those are mine. (Yes, I am the only person who draws Byzantine icons of Moe Howard.) I used to draw cartoons for fanzines. There was once a conspiracy to get me nominated for the Best Fan Artist Hugo, though the people involved have since been safely put away in nice rubber rooms where they won’t harm anyone. My most celebrated cartoon showed a bleary-eyed man in bed looking up at the ceiling. Above the ceiling, we see a suicide’s legs and feet and the end of the rope hanging down, a note pinned on his pants cuff. One of his shoes has fallen off. The guy below him is thinking, “Come on…drop the other damn shoe!”

That’s my problem. Interested in too many things. Not enough focus.

What are your goals for the next phase of your fiction-writing career?

What are your goals for the next phase of your fiction-writing career?

I need to write a new novel. I also need to write something which is as distinctly different from the rest of my work as Tom O’Bedlam is from Julian and Julian is from Sekenre. I need to find the next phase, lest I start repeating myself.

What advice would you give to today’s newest generation of fantasy writers?

Be satisfied with small successes — but only for a time. It’s all well and good to sell your story for two or three cents a word to a magazine with a circulation of two thousand. A lot of us depend on this. It is well and good to have your book published by a small (but not a vanity) press. But keep in mind that bigger things are possible. Don’t settle down too early.

Finally, are there any appearances, stories, or book publications that you would like to plug here?

Well, I sold a story called “Into the Gathering Dark” to Black Gate recently. Among other things forthcoming, look for “A Lost City of the Jungle” in a James Lowder anthology of multi-genre pulp fiction. This is my only “jungle story,” though I think it owes more to Dunsany’s Jorkens than to Edgar Rice Burroughs. Look too for “Fighting the Zeppelin Gang” in Postscripts next year. I have stories forthcoming in H. P. Lovecraft’s Magazine of Horror, one a reprint from Interzone, the others originals.

Beyond that, Peter Crowther’s PS Publishing is publishing as a short book my story-cycle (which is arguably one long story) of the Corpsenberg stories. You have seen one of these in Weird Tales before the policy-switch, “The Most Beautiful Dead Woman in the World,” in #337. The first three were published in Interzone under the old regime, but the new editor did not choose to continue with them, which left Interzone readers on a bit of a cliffhanger. There are five stories in all. They form a distinct unit, each story feeding into the next. I admit this is modeled on Zoran Zivkovic’s story-cycles.

“The Eater of Hours” is another story forthcoming in Allen Koszowski’s Inhuman magazine. It’s a medieval story, as dark as anything in the Julian series, and it’s full of strangely twisting perceptions. The characters are a bunch of thugs who got lost on the way to the crusades. They are trapped by…what? A web of illusion? A Thing from outer space? Are they all dead before the story starts, their memories being played out in the mind of the creature that devoured them? Read it and see….

I have recently signed contracts with Wildside Press’s Borgo Press imprint for a new poetry collection, a new essay collection, and Speaking of Horror II, a book of interviews.

If someone is coming to this interview having read little or nothing of mine, I would say go out and buy The Mask of the Sorcerer, Nightscapes, and Refugees from an Imaginary Country. I will give my personal guarantee. If you can read those three books cover-to-cover and find nothing of interest in them, you have my permission to give up. You won’t get your money back, but you do have my permission to give up. Those three would make an adequate sampler of what I am about as a fiction-writer.

Thanks, Darrell! On a final note, The Mask of the Sorcerer, The White Isle, Nightscapes, and all other Schweitzer books mentioned above are available at www.amazon.com and www.wildsidepress.com. All are essential reading for fans of fantasy and horror. (Especially Mask!)

2 thoughts on “The Sorcery of Storytelling: The “Imaginary Worlds” of Darrell Schweitzer”