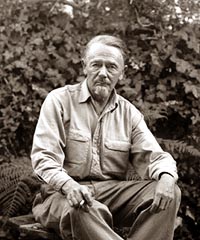

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith PART III: Tales of Zothique

by Ryan Harvey

All rights reserved. Copyright 2006 by New Epoch Press.

When Robert E. Howard discovered the character Conan in 1932, his writing took on a feverish intensity as the barbarian warrior turned into a literary obsession that allowed his creator’s natural skills and inclinations as a writer to bloom. Likewise in 1932, when Clark Ashton Smith discovered the last continent of dying Zothique, he knew that he had found the ideal setting for his poetic and dark imagination to run rampant. The lengthy series of Zothique tales (sixteen finished stories, a poem, and a one-act play) contains some of the most superb examples of Smith’s fiction work, with classic after classic pouring out at a quick pace.

When Robert E. Howard discovered the character Conan in 1932, his writing took on a feverish intensity as the barbarian warrior turned into a literary obsession that allowed his creator’s natural skills and inclinations as a writer to bloom. Likewise in 1932, when Clark Ashton Smith discovered the last continent of dying Zothique, he knew that he had found the ideal setting for his poetic and dark imagination to run rampant. The lengthy series of Zothique tales (sixteen finished stories, a poem, and a one-act play) contains some of the most superb examples of Smith’s fiction work, with classic after classic pouring out at a quick pace.

In a letter to H. P. Lovecraft, Smith gave a tongue-in-cheek description of Zothique:

I have heard it hinted in certain archaic and obscure prophecies that the far future continent called Gnydron [Smith’s abortive early name for the continent] by some and Zothique by others, which will arise millions of years hence… and will witness the intrusions of things from galaxies not yet visible…

However, Smith did not write of Zothique simply as a bizarre future-world that serves as a magnet for the strange. He made it something darker and more powerful: the final stage of life on Earth. The opening of one of the finest stories of the series, “The Dark Eidolon,” provides an excellent summation of the peculiar qualities of this last land, where….

However, Smith did not write of Zothique simply as a bizarre future-world that serves as a magnet for the strange. He made it something darker and more powerful: the final stage of life on Earth. The opening of one of the finest stories of the series, “The Dark Eidolon,” provides an excellent summation of the peculiar qualities of this last land, where….

…the sun no longer shone with the whiteness of its prime, but was dim and tarnished as if with a vapor of blood. New stars without number had declared themselves in the heavens, and the shadows of the infinite had drawn closer. And out of the shadows, the older gods had returned to man…. And the elder demons had also returned, battering on the fumes of evil sacrifices, and fostering again the primordial sorceries.

In Clark Ashton Smith’s writing, humanity does not progress in a straight line but moves in cycles of rises and falls, with an emphasis on the fall. Zothique represents the period of entropy; the cyclic nature of history (as embodied by Poseidonis and Hyberborea, powerful civilizations that crumbled) cannot last forever and must eventually deplete all of its energy. The ‘weak’ sun that burns over the last continent shows how drained the world’s life-force has become. With no history ahead of it, Zothique literally has only the past: crypts, mummified rulers, and the hollow remains of metropolises. Few living cities exist, and “the sands of Zothique are full of lost tombs and cities.”

Zothique reverses the ‘Pangaea’ geological theory that all of Earth’s continents were once grouped together into a primeval ‘super-continent.’ Zothique is a single continent at the close of Earth’s history, but far from a conglomeration of all lands, it is the only piece of land that remains. Progress has failed along with land; sorcery has reclaimed the role that science usurped from it millennia ago, much like in Jack Vance’s later “Dying Earth” books, which have much thematically and stylistically in common with Zothique.

Mortality defines the majority of the stories. Although a fixation on death permeates Smith’s oeuvre, in Zothique it stands on a funeral pyre and shouts its name as the flames devour it. The writer’s earlier fantasy settings of Hyperborea and Poseidonis are both doomed lands, but Zothique is the last doomed land, the death rattle of the planet Earth. It is an “End of History” scenario; its end is the world’s end, and nothing will come after. This is death as complete oblivion, not an opportunity for rebirth.

Mortality defines the majority of the stories. Although a fixation on death permeates Smith’s oeuvre, in Zothique it stands on a funeral pyre and shouts its name as the flames devour it. The writer’s earlier fantasy settings of Hyperborea and Poseidonis are both doomed lands, but Zothique is the last doomed land, the death rattle of the planet Earth. It is an “End of History” scenario; its end is the world’s end, and nothing will come after. This is death as complete oblivion, not an opportunity for rebirth.

Since they have no concept of a future, the people of Zothique live as if there were no tomorrow. Their sensual decadence forms an important sub-theme of the series that emerges strongest in the later works. The elites of the great cities live in perfumed splendors and sexual excess, as in “The Dark Eidolon” and “The Garden of Adompha.” Funerals, such as in “The Death of Ilalotha,” are cause for drunken debauchery instead of reverence. No other of Smith’s stories strain so forcibly against the boundaries of the erotic; he even planned a short Zothique novel, The Scarlet Succubus, which he claimed would explore “the imaginative and mystic possibilities of sex,” apparently outside the prudish constraints of magazine publication of the time. Sadly, work on it never progressed past the idea stage, and we are left only with the dark sexual titillations of the later Zothique pieces.

According to Smith’s letters, Zothique lies in the southern Atlantic and comprises Asia Minor, Arabia, Persia, India, parts of northern and eastern Africa, and the Indonesia archipeligo. A “new Australia” exists in the south, probably the large island of Cyntrom. The people come from Aryan (in the older use of the term) and Semitic stock. A sketchy geography can be worked out from the stories themselves. The principal lands are Yoros, renowned for its wine and its capital of Faraad (also spelled Pharaad) on the southern sea; Tasuun, a desert realm with its capital at Miraab, which replaced the cursed city of Chaon Gaca; Xylac, a decadent kingdom with its capital at Ummaos; the eastern land of Ustaim; the gray country of Tinarath; and the wastes of Cincor. In the northwest is the black kingdom of Ilcar, although it remains on the fringes of the stories. There are three islands of repulsive repute-Naat, Sotar, and Uccastrog-that harbor particularly vile customs, such as the torturers of Uccastrog and the necromancers of Naat.

The composition of the Zothique cycle falls into three phases. The first ten stories cover the last two years of Clark Ashton Smith’s longest sustained period of prose fiction production, 1928 through 1934. When Smith took up fiction again in late 1935, he completed four more Zothique stories. In the late 1940s, he again made a brief return to the last continent for a final gleaming of its moribund sun. When Clark Ashton Smith died in 1961, he was still planning to get his complete “Tales of Zothique” collected and published.

The composition of the Zothique cycle falls into three phases. The first ten stories cover the last two years of Clark Ashton Smith’s longest sustained period of prose fiction production, 1928 through 1934. When Smith took up fiction again in late 1935, he completed four more Zothique stories. In the late 1940s, he again made a brief return to the last continent for a final gleaming of its moribund sun. When Clark Ashton Smith died in 1961, he was still planning to get his complete “Tales of Zothique” collected and published.

His wish would come true more than a decade after his death, when Lin Carter published the collection Zothique as part of his Adult Fantasy series for Zebra Press. Carter included a map of Zothique that Smith had approved and emended during his lifetime. Carter arranged the stories in a dubious chronological order based on vague internal references. While the Hyperborea and Averoigne stories have some obvious chronological relations, Zothique contains few. Approaching the series in the chronological order of their composition (based on Smith’s notes), as Necronomicon Press did in their 1995 collection, Tales of Zothique, presents the stories in the best light. The following overview uses Necronomicon’s order.

“The Empire of the Necromancers”

“The Empire of the Necromancers”

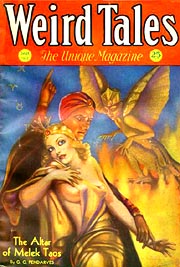

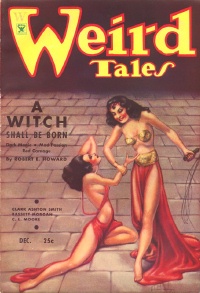

Completed January 1932. First published in Weird Tales, September 1932.

The opening paragraph of the inaugural Zothique story immediately casts a potent spell. Clark Ashton Smith had found his new fictional home:

The legend of Mmatmuor and Sodosma shall arise only in the latter cycles of Earth, when the glad legends of the prime have been forgotten. Before the time of its telling, many epochs shall have passed away, and the seas shall have fallen in their beds, and new continents shall have come to birth. Perhaps, in that day, it will serve to beguile for a little the black weariness of a dying race, grown hopeless of all but oblivion. I tell the tale as men shall tell it in Zothique, the last continent, beneath a dim sun and sad heavens where the stars come out in terrible brightness before eventide.

All writers strive for paragraphs of this potency, which impart more to a reader about the story that follows and its theme, mood, and setting than the words on the page at first indicate. Without giving a history or survey, Smith expresses a vivid portrait of Zothique’s essence that goes beyond this one story to encompass the whole cycle. Words crash like hammers onto anvils, words we shall come to know well in the stories that follow: ‘black weariness,’ ‘dying race,’ ‘hopeless,’ ‘oblivion,’ ‘dim sun,’ ‘sad heavens.’

“The Empire of the Necromancers” tells of the fatigue of a race that yearns for oblivion. It is not a dying race, but one already dead: the population of Cincor perished in an epic plague that left a desert of skeletons and sun-withered mummies in its wake. Two exiled sorcerers raise the kingdom from the dead and enslave the shambling corpses, letting them shuffle about in forgetful imitations of their former lives. But the strength of longing for true death proves too powerful for the former living of Cincor, and the first and last rulers of the royal family awaken from their thralldom to plot revenge against the sybaritic sorcerers who cheated them of death’s release.

“The Empire of the Necromancers” is frequently cited as Smith’s greatest work of short fiction. It is an ideal curtain-raiser for his most fully realized fantasy opus.

“The Isle of the Torturers”

“The Isle of the Torturers”

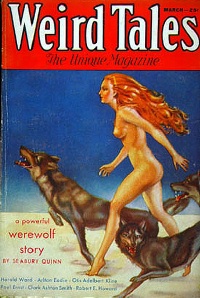

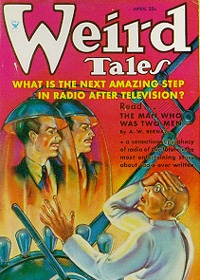

Completed July 1932. First published in Weird Tales, March 1933.

Few of Clark Ashton Smith’s stories contain such torment and suffering as this one. The title alone indicates that this is not a story for the timid reader. Taking a cue from Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death,” the story visits a horrible plague — ‘The Silver Death’ — on the city of Yoros. All the inhabitants succumb except for young King Fulbra, whose magic ring shields him from the space-born contagion. However, he can never remove the ring from his finger or he will die instantly. A lonely, cursed man, Fulbra sails into the southern ocean until a storm washes him up on the island of Uccastrog, better known as the Isle of the Torturers — for frightfully good reason.

Smith’s prose delights in the viciousness of the torments inflicted on Fulbra and his companions. Torture straddles the concept of fascination with and fear of death, making it an ideal sub-theme of the Zothique stories. Smith presents death as a blessed relief, with existence as the torture. Beneath its gruesome veneer, “The Isle of the Torturers” makes death a pleasant prospect: the ultimate escape from pain.

“The Charnel God”

“The Charnel God”

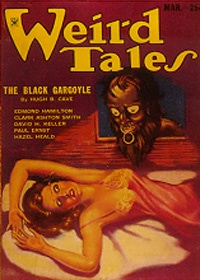

Completed November 1932. First published in Weird Tales, March 1934.

In the city of Zul-Bha-Sair, death rules in the shape of the god Mordiggian: all the dead belong to him. But on one ghastly night, two men dare to enter Mordiggian’s temple and face the masked priests whom rumor says are not fully human (possibly related to the Ghorii in “The Tomb-Spawn”) so they can steal two bodies pledged to the death-god. The sorcerer Abnon-Tha wishes to reanimate the corpse of the noblewoman Arctela and escape with her; young Phariom wants to rescue his wife Elaith, who lies in a death-like catalepsy. The result of these two men’s violation of Mordiggian’s temple makes for the most straightforward and adventurous of the Zothique stories. Smith’s linguistic arabesques are more subdued in service of a stronger plot. The story’s sheer excitement, which borders into sword-and-sorcery territory, makes it memorable. Smith borrows from the medieval legends of ghouls-canine creatures who feast on corpses in cemeteries-and tips his hat to his correspondent H. P. Lovecraft’s examination of the creatures in “Pickman’s Model” (Weird Tales, October 1927).

“The Dark Eidolon”

“The Dark Eidolon”

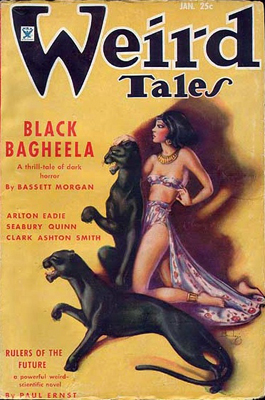

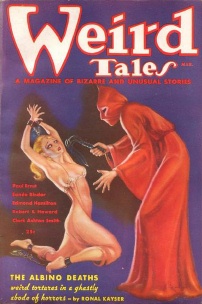

Completed December 1932. First published in Weird Tales, January 1935.

At least once per series, Clark Ashton Smith creates a title that forces readers to scrounge up a dictionary. ‘Eidolon’ means an apparition, phantom, or idealized figure. Here it signifies a statue of the god Thasaidon filled with the evil deity’s presence. Ironically, the Thasaidon eidolon espouses the most moral stance in the story and shows a degree of wisdom the mortal characters lack: he warns that it is irrational to taken revenge on a person whose transgressions against you are what is responsible for making you powerful in the first place. But rationality is a weak force in Zothique, and the sorcerer Namirrah ignores the warnings of Thasaidon as he plots against the king who slighted him as a youth and set him on the road of necromancy.

Namirrah orchestrates his theatrical vengeance against the indolent emperor Zotulla of the equally indolent country of Xylac. Namirrah never forgot an incident in childhood when the youthful Zotulla insulted him, and he has dedicated his adult life to getting even in the most magnificently morbid way he can devise. Namirrah summons a vast edifice into the middle of Xylac’s capital and forces Zotulla to attend a feast there. Namirrah presents a hideous parade of necromantic ‘entertainments’ for the Emperor before he offers up his revenge for dessert. But Namirrah should have paid attention to Thasaidon’s advice; in Zothique vengeance has an uncanny way of changing into irony.

“The Dark Eidolon” is the longest Zothique story and the most minutely embellished. (The original and now lost manuscript ran even longer.) The various horrors that Namirrah conjures are repulsive but hypnotic, and the vision of the annihilation of Xylac beneath the hooves of literal “Horsemen of the Apocalypse” is a miniature cameo of the fate of all of Zothique. However, Smith’s layered prose overstays its welcome as he lets his personal romance with his tomb-blackened prose bog down the telling. Nonetheless, the work has a central place in the cycle because of its sustained presentation of images born of death and decay and the irony of Namirrah’s fate.

“The Voyage of King Euvoran”

“The Voyage of King Euvoran”

Completed January 1933. First published in The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies, Auburn Journal 1933.

This story has an unusual origin. Smith conceived it as part of his Hyperborean cycle, but it eventually mutated into a chronicle of Zothique. Pulp scholar Will Murray credits this to Smith’s fixation on Zothique at the time, but considering the difficulties the author had selling his Hyperborean stories to Weird Tales, the choice to switch to a series with a better sales record may have been economic. If this is the case, the switch failed. Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright rejected “The Voyage of King Euvoran.” Smith included the story in a 1933 self-published chapbook. It eventually appeared in Weird Tales in September 1947, but in an abridged form re-titled “Quest of the Gazolba.”

Despite the switch in setting, at heart “The Voyage of King Euvoran” belongs to satirical Hyperborea, not humorless Zothique. The story has little in common with the sepulchral overtones of the last continent and does not touch on its theme of mortality. It instead tells the picaresque odyssey of the eponymous anti-heroic king of Ustaim who hunts for a gazolba bird in the eastern islands to replace the one that a necromancer stole from his crown. During his voyage, Euvoran encounters vampires and a topsy-turvy island where birds practice taxidermy on humans — a satirical touch standard for a Hyperborean story, but out of place in Zothique. Smith’s ironic elevated descriptions start to feel stale after a span, a flaw that also damaged a number of the Hyberborea stories.

The shortened re-write, “Quest of the Gazolba,” is a rarity that has never appeared in a print since its Weird Tales publication. Smith reduced the original length by a third, eliminating the sequence with the vampires and shaving off much of the extra description. The changes neither help or hurt the original.

“The Weaver in the Vault”

“The Weaver in the Vault”

Completed March 1933. First published in Weird Tales, January 1934.

This minor story takes place in the most appropriate location imaginable for a tale of Zothique: a tomb. The simple plot falls into the category of “monster story” where the protagonists confront a bizarre supernatural entity. It has much in common with the Hyperborean yarn “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros,” where tomb robbers enter an abandoned capital to loot the treasures of its king, only to meet an inhuman guardian and suffer grisly consequences. The looters in “The Weaver in the Vault” are servants of the King of Tasuun, who has dispatched them to retrieve the mummy of the founder of his dynasty from the ruins of the abandoned capital Chaon Gacca. In the tombs the king’s soldiers do not find undead horrors as they might have expected, but something deadlier…and also surprisingly beautiful. The tomb’s weird guardian is a memorable creation in an otherwise average story.

“The Tomb-Spawn”

“The Tomb-Spawn”

Completed July 1933. First published in Weird Tales, May 1934.

Farnsworth Wright initially rejected this story for Weird Tales, probably because of its similarity to “The Weaver in the Vault,” although he eventually bought it (after Astounding also rejected it, although it seems unlikely a science-fiction magazine would seriously consider a work of outright fantasy). The story repeats the previous tale’s narrative of men who enter a tomb in a forgotten city and face its fearful denizen. Two jewelers lost in the desert after an attack by the ghoulish Ghorii wander into the ruins of the city of King Ossaru, a ruler who once controlled half of Zothique. A legend the two jewelers heard from a bard claims that Ossaru buried himself in a vault beneath the city alongside a star-born monster named Nioth Khorgai. The two hapless men soon find out the truth of the legend.

Although it uses a recycled plot, its nihilistic conclusion elevates “The Tomb-Spawn.” The result is oblivion, a mirror of Zothique’s own expiration from entropy. This is not a death that will lead to new life, or even a death that can benefit others (such as the corpse-eating Ghorii), but the final end of all: “a tomb empty of either life or death,” Smith writes.

“The Witchcraft of Ulua”

“The Witchcraft of Ulua”

Completed August 1933. First published in Weird Tales, February 1934.

How Smith managed to convince Farnsworth Wright to publish a tale immersed in sexually repulsive images, especially after Wright rejected it once, is perplexing. In its flood of descriptions both lascivious and nauseating, such as couplings with maggoty corpses, “The Witchcraft of Ulua” shares a common quality with the Averoigne story “Mother of Toads.” But where the earlier story shows the horrid consequences of a young man rejecting the sexual advances of a haggish sorceress, “The Witchcraft of Ulua” brings judgment down on its titular seductress. Ulua, the daughter of the king of decadent Tasuun, is no hag, but “of elf-folk” (the story does not elaborate on what this means) with a voice like “hot honey.” When cupbearer Amalzain refuses her charms, she inflicts him with a curse that unleashes a flood of Smith’s most vivid grotesques. The story is simple and contains something of a prudish moral that Smith probably didn’t believe himself, but the erotic content shows the promise that was lost when Smith’s planned novel The Scarlet Succubus vanished into the creative ether.

“Xeethra”

“Xeethra”

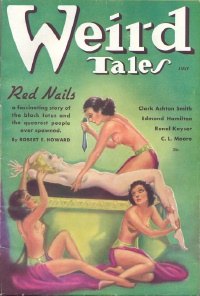

Completed March 1934. First published in Weird Tales, December 1934.

The tale of the young shepherd Xeethra seems to say that in a dying world, the ultimate curse is memory. While guarding his uncle’s flocks in arid eastern Cincor, Xeethra discovers a cavern that leads to a lush and unfamiliar world. He eats the red fruit of a tree and gains the memories of King Amero of Calyz. Amero’s memories soon subsume Zeethra’s, and the boy sets out across Zothique to find the capital of his kingdom. But like so many other cities on the last continent, Calyz has withered to dust. A deal-with-the-devil (or deal-with-Thaisadon) grants Amero a chance to relive the glory days of Calyz in exchange for his soul, but he suffers a second memory curse, one that makes taking his soul unnecessary.

“Xeethra” is one of the best of the Zothique stories, and also the gentlest. The prose is filled not with hideousness or necromancy-spawned descriptions, but with gentle yearning and regret. The theme of memory — handled in a similar way in the Poseidonis story “The Last Incantation” — is a potent one, for it is memory that gives perspective to a dying land. It is possible for people to find contentment in a land slipping into oblivion as long as they remain oblivious of its glorious past. Here Smith makes Zothique appear welcoming, and Xeethra’s life as a shepherd an enviable one. Poor Xeethra: ignorance really is bliss.

“The Last Hieroglyph”

“The Last Hieroglyph”

Completed March-May 1934. First published in Weird Tales, April 1935.

Smith intended this story to conclude the planned “Tales of Zothique” volume. It would also be the last story he would write for some time. Although more Zothique stories would follow, “The Last Hieroglyph” is thematically the curtain-closer. The Astrologer Nushain, living in the city of Ummaos (restored since the apocalypse of “The Dark Eidolon”), charts his destiny in the sky and sees that three entities will take him on a long journey. In a turn of events reminiscent of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, three otherworldly guides appear in succession to shepherd Nushain along his unknown path.

As a story, “The Last Hieroglyph” offers few rewards other than a bizarre itinerary through supernatural wonders, and it contains few traces of what might be called a plot. Its theme and position as the terminal Zothique story are what make it memorable. It reduces fantasy to the medium of writing, as if Smith is overtly subsuming all his work from the realm of the fantastic into the basic element of raw text on a page. The entity Vergama — a god, or demon, or sorcerer, or alien — claims to have originated all things in his book, where…

“…the characters of all things are written and preserved. All visible forms, in the beginning, were but symbols written by me; and at the last they shall exist only as the writing of my book. For a season they issue forth, taking to themselves that which is known as substance…. It was I, O Nushain, who set in the heavens the stars that foretold your journey; I who sent the three guides. And these things, having served their purpose, are but infoliate ciphers, as before.”

Vergama indicates something like Plato’s theory of forms, except the perfect form of which our world is merely a reflection is in this case writing. Vergama could very well be Clark Ashton Smith himself, at the (presumed) close of his career, taking all his works and returning them to the page, the only place they actually exist.

Smith wrote a short prologue to “The Last Hieroglyph,” titled “In the Book of Vergama,” but it did not appear in the original Weird Tales publication and would not make its print debut until 1989. It adds a level of tension to the story by introducing the mystery of Vergama, but its excision tightens the point of view, keeping it restrained to what Nushain experiences.

“Necromancy in Naat”

“Necromancy in Naat”

Completed February 1935. First published in Weird Tales, July 1936.

“The Last Hieroglyph” turned out to be a false prophecy. Less than a year later, Clark Ashton Smith re-opened his personal copy of the Book of Vergama and completed a new chronicle. “Necromancy in Naat” harkens back to the start of the cycle, combining ideas from “The Empire of the Necromancers” and “Isle of the Torturers,” and bringing on-stage for the first time the frequently mentioned island of Naat. Smith dropped so many baleful hints about this isle that he could not pass up an opportunity to make it the center of a story. As in “Isle of the Torturers,” the plot concerns a member of royalty (Yadar, a nomad prince in the land of Zyra) on a desperate quest who accidentally shipwrecks on the shores of an island of shuddersome repute. As in “The Empire of the Necromancers,” decadent sorcerers have animated legions of the dead to serve them, and the bittersweet taste of death serves as an ironic conclusion. Smith remains in fine form as a writer after his hiatus, but some of the passion for Zothique has ebbed; the author had, after all, imagined himself finished with the cycle. Comparison to the earlier works from which “Necromancy in Naat” borrows makes the difference in the writer’s enthusiasm even clearer. The story might have been stronger if Farnsworth Wright had not forced Smith to rewrite the ending to make it more upbeat. However, the original has gone the way of many of Zothique’s kingdoms… lost to time.

“The Black Abbot of Puthuum”

“The Black Abbot of Puthuum”

Completed Spring 1935. First published in Weird Tales, March 1936.

The archer Zobal and the pikeman Cushara are headed back to Faraad, with a newly purchased beauty for the king’s harem, when they come across the mysterious Abbey of Puthuum in the desert wastes and meet its oddly repulsive abbot. The events that follow are not much different from a standard dark fantasy adventure, and the result is the most unsurprising of the Zothique stories. Smith livens up the action with doses of his word sorcery and cadaverous obsessions, but “The Black Abbot of Puthuum” feels more calculated to make a sale than the earlier Zothique pieces, and for once Smith’s archaic prose hinders more than helps. Nonetheless, the story succeeds as an adventure tale even if it lacks the visceral staying power of the author’s best work. The unusual romantic finale adds a pleasant sting for readers as they put the piece down.

“The Death of Ilalotha”

“The Death of Ilalotha”

Completed March 1937. First published in Weird Tales, September 1937.

Almost two years passed before the next Zothique story. It appears Clark Ashton Smith was consciously returning to the strength of his earlier work with “The Death of Ilalotha.” It abandons plot almost altogether for the sake of necromantic imagery. The story opens with the funeral observances of Ilalotha, lady-in-waiting to the queen of Tasuun. The commemoration of the dead is a raucous and bacchanalian affair that seems more appropriate for a wedding celebration.

…from morning to dusk to sunset, from cool even to torridly glaring dawn, the feverish tide of the funeral orgies had surged and eddied without slackening…. Mad songs and obscene ditties were sung, and dancers whirled in vertiginous frenzy to the lascivious pleasing of untirable lutes. Wines and liquors were poured torrentially from monstrous amphoras; the table fumed with spicy meats piled in huge hummocks and forever replenished. The drinkers offered libation to Ilalotha, till the fabrics of her bier were stained to darker hues by the spilt vintages. On all sides around her, in attitudes of disorder or prone abandonment, lay those who had yielded to amorous licence or the fullness of their potations.

To this debauched celebration returns Lord Thulos, the queen’s lover and also a paramour of the dead lady-in-waiting. A voice from the corpse urges him to come to a rendezvous in her tomb later that night. The jealous queen also learns of the tryst and follows Thulos. The finale plunges readers into one of the author’s most elegant descriptions of the houses of the dead. Although the chronicles of Zothique have visited this territory before, here it feels renewing after the missteps of the previous two stories.

“The Garden of Adompha”

“The Garden of Adompha”

Completed July 1937. First published in Weird Tales, April 1938.

King Adompha of Sotar, another of the isles of Zothique famous for unwholesome practices, maintains a gruesome garden sown with human limbs grafted onto plants. Servants who have displeased the king end up as raw material for this horticultural horror: “A bare, leafless creeper was flowered with the ears of a delinquent guardsman…. Some of the salver-like blossoms bore palpitating hearts, and certain smaller blossoms were centered with eyes…” In the space of the story, Adompha adds two more servants to the garden, but his next visit will be his last. Although this is one of the shortest of the stories, “The Garden of Adompha” excels at sickening descriptions balanced with an amoral perspective. Adompha receives a comeuppance for his actions, but the prose remains distant and passes judgment neither on the king or his victims. The garden’s revenge is not an action of moral outrage, it is simply the logical balance of life in the last continent. This aspect of Smith’s handling of Zothique appears throughout the series; even as people receive punishment for ‘wicked’ deeds, the sensuous but objective prose indicates that standard morality no longer functions in a land so far removed from ours.

“The Master of the Crabs”

“The Master of the Crabs”

Completed August 1947. First published in Weird Tales, March 1948.

After 1937, Clark Ashton Smith’s fiction output slowed to a trickle, and his attention turned back toward his first field, poetry. He had used the income from his magazine sales to support his ailing parents, and with his mother’s death in 1935 and his father’s in 1937 one of his primary motivations disappeared. He had also lost his two favorite correspondents and co-conspirators in the Weird Tales revolution, Robert E. Howard and H. P. Lovecraft, to suicide and intestinal cancer respectively. Their loss contributed to his waning interest in short stories. He returned to the form in 1943, but wouldn’t pen a new Zothique chronicle until 1947, almost ten years after the last one. “The Master of the Crabs,” like “The Black Abbot of Puthuum,” takes place in the familiar confines of a straightforward fantasy adventure: two wizards compete to reach a treasure on a distant island.

Weird Tales was now under the editorship of Dorothy McIlwraith, who had pushed the magazine in less prose-poetic directions since taking over from Farnsworth Wright; Smith may have written the story to appeal to her preference for more plot-driven work. “The Master of the Crabs” works better than “The Black Abbot of Puthuum” with its more concise storytelling, and the finale featuring the title creatures is shivery even if it arrives without sufficient suspense. Another point of interest: this is the only chronicle of Zothique written from the first-person perspective.

“Morthylla”

“Morthylla”

Completed Fall 1952. First published in Weird Tales, May 1953.

“Morthylla” is the last complete short story of Zothique. Appropriately enough, it is also the most oblique. It has a circular, ambiguous ending involving a man who kills himself, but “forgets” that he has died. A meeting in graveyard, a debauched party… the customary business of the last continent is all here, but the brush strokes of Smith’s pen are lighter and vaguer than before. The story also contains suggestions that Smith has put himself into his work to add a personal perspective. The protagonist, Valzain, is a young poet for whom earthly pleasures no longer have any meaning, and restlessness afflicts him. His dreams taunt him with a beautiful and unreal world: “Do such dreams have any source, outside the earth-born brain itself? I would give much to find that source, if it exists. In the meanwhile there is nothing for me but despair.” It is easy to imagine the aging Clark Ashton Smith, a poet for nearly forty years, pondering such questions.

“The Dead Will Cuckold You”

Completed 1952. Revised 1956. First published in In Memoriam: Clark Ashton Smith, The Anthem Series 1963.

The final completed work of Zothique is a peculiarity: a one-act closet drama (a play never intended for performance) in six scenes of blank verse. Smith considered it one of his finest works. It takes place in Faraad, where the king murders a poet on whom his wife has lavished too much attention. A necromancer fulfills the promise of the title when she resurrects the murdered man. Stage drama would initially seem an ill-fit for a prose stylist like Clark Ashton Smith, especially since his stories rarely rely on dialogue. But if “The Dead Will Cuckold You” isn’t nearly the masterpiece that Smith considered it, it is nonetheless a unique and effective work of poetry. That it would never work on stage physically or dramatically is a useless criticism; the author never meant it for production. As a poetic presentation through dialogue and a few stage directions, it casts a hypnotic spell. The Elizabethan-inflected verse gives a sense of ancientness to Zothique, and the rigid and regal presentation conveys the dying spelndors. The ending is abrupt, almost absurd, but plot development is not the point. The rhymthmic poetry is why it works. Smith should have dabbled more in closet drama, since the medium melds his poetic work with his prose fiction in an ideal way.

Fragments

Fragments

Aside from the completed stories, a few fragments of Zothique survive, none of them lengthy. “Shapes in Adamant” was Smith’s first attempt at a new Zothique story after his 1935 break from fiction writing, but after only a few pages he abandoned it and turned to writing “Necromancy in Naat.” Probably written during the last stage of Smith’s short story writing in the 1950s, “Mandor’s Enemy” is three paragraphs about the fears of a prince of Tasuun. Both fragments were first published in 1984 in Crypt of Cthulhu #27. An intriguing short poem of indeterminate date, “Zothique,” appeared in the Arkham House 1951 collection The Dark Chateau and Other Poems.

“I doubt if any of my work will ever have a wide public appeal,” Smith wrote in a 1937 letter to artist Virgil Finlay, “since the ideation and esthetics [sic] of my tales and poems are too remote from the psychology of the average reader. It is reassuring, however, that my work should appeal so strongly to a few.” Ray Bradbury would later echo this sentiment in a posthumous tribute to the writer, noting that Smith appealed to special kinds of readers, and that his fame was “lonely.”

Perhaps this lonely fame affects appreciation of his work. Smith’s writing will always stand apart from other fantasy, off in its own baroque and difficult to categorize cubbyhole. Zothique, of all Clark Ashton Smith’s fantasy creations, stands as the loneliest. Love does not conquer here, as it sometimes does in Averoigne. Readers will find no sneering roustabout rogues, as they often encounter in Hyperborea. And no life will come after the sun over the last continent at last sputters and dies. For a poet of lonely fame, Zothique must have felt much like home. It remains the most fascinating legacy of the Master of Poetic Morbidity.

“Dear reader, please, one step forward and a long step down,” Bradbury wrote to conclude an introduction to a Clark Ashton Smith anthology. He might have added that the fall to the Zothique is the longest, and the most difficult from which to return.

Our recent coverage of Clark Ashton Smith includes:

New Treasures: The End of the Story: The Collected Fantasies, Vol. 1 by Clark Ashton Smith

Vintage Treasures: The Timescape Clark Ashton Smith

The Shade of Klarkash-Ton by James Maliszewski

One Shot, One Story: Clark Ashton Smith by Thomas Parker

New Treasures: The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies by Clark Ashton Smith

The Crawling Horrors of Mars: Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis”

Deepest, Darkest Eden edited by Cody Goodfellow by Fletcher Vredenburgh

Adventures in Stealth Publishing: The Return of the Sorcerer

A Few Words on Clark Ashton Smith by Matthew David Surridge

The Unqualified Unique: The Daily Mail Interviews Me for Clark Ashton Smith’s 50th Morbid Anniversary by Ryan Harvey

Of Secret Worlds Incredible: A Psychedelic Journey into Clark Ashton Smith’s Poetic Masterpiece by John R. Fultz

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part I: The Averoigne Chronicles by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part II: The Book of Hyperborea by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part III: Tales of Zothique by Ryan Harvey

The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith Part IV: Poseidonis, Mars, and Xiccarph by Ryan Harvey

6 thoughts on “The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith PART III: Tales of Zothique”