Black Gate Online Fiction: “The Shadow of Dia-Sust”

By David C. Smith

This is a complete work of fiction presented by Black Gate magazine. It appears with the permission of David C. Smith and New Epoch Press, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Copyright 2014 by David C. Smith.

For

Retired U.S. Army SFC Robert Price, Sr.

1.

The Outlander

We bargain for the graves we lie in.

— James Russell Lowell

The Vision of Sir Launfal

Bodor moved quickly, faster than Oron had anticipated, and Oron paid for his slowness: Bodor’s bleeding knuckles hit the younger man hard on the left side of the face and scraped painfully along his ear. Still, Oron managed to twist away as Bodor reached for the young man’s long hair. Bodor missed — and leaned off balance.

Bodor moved quickly, faster than Oron had anticipated, and Oron paid for his slowness: Bodor’s bleeding knuckles hit the younger man hard on the left side of the face and scraped painfully along his ear. Still, Oron managed to twist away as Bodor reached for the young man’s long hair. Bodor missed — and leaned off balance.

Oron moved in. He punched Bodor’s bare skin powerfully at the ribs. Bones cracked, and Bodor winced. He stepped away with his mouth open.

Around them, at the fires that circled the open yard in the middle of the war camp, laughter and cheers came from two hundred men — fighters and killers, all of them. For this company, two angry men throwing down in blood sport was a diversion subordinate only to open combat on the red field itself.

A diversion, and a chance for winnings. They called to one another from fire to fire, warning each other to be prepared to be shamed.

“The boy’s going to put him down!”

“Get your money ready, pig! And your sister! I’m taking both!”

“Can I change my bet? Bodor’s going to break this pup in half!”

Beyond the hot campfires, seated in a tall wooden chair that had accompanied him on half a lifetime of murderous campaigns, crouched Maton, their war captain and chief. With the experience of many years, he watched these naked brutes, Bodor and Oron, each without armor, without weapons, covered only in animal skins wrapped tightly below their belts — Bodor, able to push out the eyes and tear away the throat of anyone in bare-handed combat, and this young dog who had come into camp only weeks before, alone, an outlander, clearly a fighter, but from a distant land and of a heritage legendary to Maton and his easterners, and with a history that the war chief reckoned to be lies and exaggerations.

For no one could have achieved in a lifetime what Oron the Nevgan claimed to have done in only a few years. Leading men into battle and fighting sorcerers and important chiefs both. Measuring himself against the love of proud women and winning their strong hearts. Witnessing remarkable transformations of reality within the lodge huts of mystics, shamans, and other lost souls. Spending countless nights alone under the cold stars, tracking whatever he could find alive to eat raw and squirming. Killing his own father.

His own father.

Performing an act that even renegades such as these in this camp, murderers and cutthroats every one of them, regarded as evil, direct evil.

More howls came as Bodor began circling to his right, keeping watch on Oron. He was a head taller than the outlander and thicker in the chest as well as the waist, but the young Nevgan was quicker by far with his lunges and hits and feints. Bodor had marks on him to demonstrate this: welts on his shoulders and upper arms, bleeding scratches on his chest and back, even a bite mark on his right forearm earned from an attempt to cuff Oron across the mouth.

Oron himself had not accepted as many hurts. He was bruised on the left ear and sore on his chest and jaw where Bodor had gotten inside with punches, but he had kept his ribs intact.

And he was smiling, whereas Bodor, not at all pleased that he had failed so far to take down this cub, was grimace and frown.

And taunt. “Dog,” he said to Oron. “Outlander. I’ve killed so many like you, I’ve lost count.”

Oron answered by spitting at him.

Bodor sneered, and he continued to move to his right, trying to back Oron against a nearby tree. “You’re a Nevgan pig. Do all of you pigs kill your own fathers?”

Oron lost his smile.

“Or did you do it just so you could stick it inside your own mother?”

Oron moved. Ran at Bodor. Leaned right as though intending to punch the broken ribs —

Bodor pulled back.

— then crouched forward as he ran, ducking his head.

Whoops from the campfires.

Oron rolled onto his shoulders and back. Lifted his legs. Pushed them forward so that the heels of his feet struck Bodor full on the chest.

Howls, all around.

Bodor, off balance and gasping, tripped away.

Oron got to his feet and jumped forward. He pushed Bodor in the chest. Bodor lost his balance and fell backward, crashing hard.

Oron jumped and straddled him, seating himself on the bigger man’s chest.

Bodor lifted his arms in an attempt at defense. Oron caught the wrists and held them.

Out of breath, Bodor stared up at the Nevgan.

Oron squeezed his legs together; Bodor groaned as pain oozed from his broken ribs. Oron twisted the bigger man’s wrists until the snapping bones gave way in both. Then he took Bodor’s head between his hands.

Bodor tried to speak.

Oron lifted Bodor’s head, then pushed it back down quickly, hard against the earth. He did it again. And again. Did this many times. Finally he wrapped his bleeding hands in Bodor’s hair, twisted the long hair until he had a secure grip, and stretched the head back and up until more bones broke. Oron pushed until the head could be moved no farther on the contorted neck.

If Bodor still could see from so ridiculous an angle, then his sight rested on the hot stones of a campfire somewhere above the top of his head.

But likely he saw nothing; his skull had been separated from his spine.

Oron stood, panting, and spat at Bodor again, directly onto the side of the dead man’s face. He said to the corpse, “Son of a whore. We kill our fathers and anyone else we want to. Stick it in your mother! And your father. In Hell.”

Men at the campfires hurrahed and pushed forward to clap the young man on the back, rub his hair, or punch him on the shoulders in their excitement.

“He did it!”

“I’m rich! Pay me, Butt-face!”

“I knew he could do it!”

The losers grumbled and paid their bets, then returned to their tents or bunk rolls or stumbled off into the deeper woods to urinate the beer they had drunk, as though doing that could help relieve their disappointment.

Then came a loud voice from behind the happy company of killers. “Make way! Step aside! Move!” Maton himself, taller and heavier than Bodor, even, pushed through the mob.

His black beard was stained with food and drink, and his long hair was oily and braided where it fell over the leather-and-bronze cuirass he wore. The chain loosely draped around his protected waist was woven with spikes and metal thorns, and it was weighted on one end with a heavy ball, also studded with spikes; fools had died, bleeding from opened throats, when Maton swung that weapon overhead like a wheel and then savaged those unguarded necks. And in swordplay, he was better than nearly every man in camp; few had ever challenged him, and none of those had lived.

Maton came straight at Oron and stopped an arm’s length away from him.

And did not smile.

“You killed my best man.”

“Some men need killing.”

“Which of you provoked this?”

“He took my food and called me a dog. Told me I didn’t deserve to eat the food that men eat.”

One of those near Maton, a bald, lean veteran named Agol, told the chief, “It’s true, Captain. It’s the truth.”

Maton glanced at him, then asked Oron, “Who’s going to lead these bastards into the field tomorrow?”

“Not Bodor, unless he finds a way back from Hell tonight.”

Men laughed until Maton glared at them. When he looked at Oron again, he demanded, “Who am I going to get? You?”

“Pay me what you paid Bodor, and I’ll give it some thought.”

More laughter and a few whoops. “Do it, son!” came a voice from the back.

“You can lead these men?” Maton said. “I doubt it.”

“I’ve fought animals better than Dasagak, and I’ve met him before.”

“Where?”

“South of here. I’ll stick him like a pig if you give me the chance.”

“Why didn’t you stick him like a pig when you were south of here?”

“Because he’s a cowardly pig. He ran away. He lets other men do his fighting for him.” Oron said it as he looked Maton in the eyes.

Maton smiled. “Then you lead the men. I want you out there front and center. And I want to see you do whatever you need to do to stick your pig.”

“You’ll see it. Now can I have something to drink? Killing pigs makes me thirsty.”

Maton chuckled and lifted a hand. Someone behind him produced a wine flagon, and he handed it to Oron. He asked him then, “Where did you learn that trick, jumping like that?”

“I didn’t learn it.” Oron unstoppered the flagon and lifted it to his mouth. “I thought of it. I did it because I needed to.”

“You’re full of surprises, Nevgan.”

Oron nodded as he guzzled.

“You’ll find that I’m full of surprises, too. Tomorrow,” Maton told him, “you lead the way.”

Oron slurped wine and wiped his mouth with the back of a hand. “You just be ready with something sharp to stick his head on. I’ll bring you a trophy, and I’ll get myself some honor back.”

Maton turned away, pushing past his men to go to his horsehide tent.

While half the dogs in his company once more encircled Oron and congratulated him with laughter and more hard slaps on the back.

“Could you even have hoped for such luck?” Damu asked as Maton settled into a camp chair in his tent.

“I see no luck,” the captain complained.

His bodyguard sniffed with amusement. Damu had served as Maton’s shadow for years, since losing the use of his left leg, which remained attached to his hip but was no better than a wooden prop, the meat of it dead and the muscles, weak. Maton had saved Damu’s life the day that leg had been cut nearly free by men with quick swords, killing the attackers and pulling Damu to safety as the mangled leg rolled in the dust. In gratitude for that gesture, Damu had sworn ever to assist his chief. And since earning that wound, Damu had killed many men; he was superb with a knife and able to drop birds from high in the air when he threw his daggers. And in swordplay, he was equal to nearly every man in camp, perhaps second only to Maton himself.

Now, as Maton brooded over what Oron had done to his champion, Damu said to the war chief, “It is evident to me that letting this pup lead the way tomorrow gives us the advantage of delivering him to his old enemy.”

Maton considered it, and he realized the good that could come of it. “Let that dog have Oron,” he grinned, “while we lay aside our steel?”

“Do it,” Damu urged his chief. “We pay in this way for safe passage through Dasagak’s lands. We can return to fight him another day, and on that day, we will not be outnumbered five to one.”

“I do not fear the numbers.”

“Nor do I. Nor do your wolves. But why risk losing some of these fighters when you can risk fewer of them when we return next spring?”

Maton weighed this in his mind. “Hire more men over the winter. Match Dasagak sword for sword, come spring. Pile the heads high, and increase our armory. And raid these lands at our leisure the summer long.”

“And at what price?” Damu reminded his lord. “The head of an outlander boy whose sole gift, clearly, is that he wanders into war camps where he’s more trouble than he’s worth.”

Maton laughed. “Send a rider into the chief’s camp with our pledge to let him take Oron in the morning as we stand by.”

“I’ll do it now.”

“If Oron tells the truth,” Maton said, “then Dasagak will agree to this. We’ll have our safe passage and our winter’s spell, and then all the plunder we wish next spring. If Oron lies, then he dies first in the morning. A man that kills his own father is no man at all, and he deserves no better than to be killed like a dog.”

The wind heard those words, as did the shadows outside Maton’s horsehide tent, as did a spirit waiting within those shadows.

The spirit held still, listening, then drifted on as heat might from a campfire, as a breath might when carried on the night air. The drifting spirit returned to its body hidden in a cave in the high stones of the low mountains that crouched west of Maton’s camp, west of Dasagak’s camp, west of the wide field that tomorrow was to be a blood field.

A groan, as spirit moved inside flesh and as a woman, middle-aged but weary, strong but exhausted from years of effort and change, shuddered with the return of her secret sight. There was a young woman seated in the shadows beside the sorceress, a girl of perhaps twelve years who was no more than a stick, a malnourished thing with full hair and dark eyes, dressed in someone else’s cast-off clothes. This young one touched the sorceress as she shuddered, making sure that her mistress was well enough after her challenge. The woman of spirit strength took in long breaths to awaken fully. Both then looked into the small campfire before them, the only light in this deep cave.

“Is it he?” the young woman asked.

“It is.”

“A man that kills his own father is no man at all.. .”

This is what the sorceress had heard. This is why she had followed the signs in the stars, followed the indications shown her when she read the smoke and had the young woman cast colored bones. The signs and indications had led her here, far from her original home, so that she could complete the destiny she had devised for herself.

She could not complete that task alone, the stars had told her, and her bones and her visions.

She would need assistance.

And this man who had killed his own father offered precisely the assistance that was needed.

2.

Betrayal

I wish only that my fury would drive me to hack your meat away and eat it raw for the things you have done to me.

— Homer, Iliad

Book XXII, 408-410

Before dawn, as the earliest sunlight fell through the heavy mists on the wide field, Oron sat his horse and watched as Dasagak’s one thousand aligned themselves in the distance, facing him. Beside the Nevgan wolf, to his right and left, sat six others ordered to advance with him — one of them the old, tough Agol, the others, younger fighters chosen personally by Maton and Damu.

And behind the seven of them, waiting upon the grassy slope of the valley wall to the south, were Maton and his hundreds.

At a signal from Oron, these hundreds would advance.

The morning brightened. The gray mists lifted. Birds called from the outcroppings, the rocks and deep forests on either side of the flat plain.

Now the infantry at Dasagak’s front line pounded their weapons against their heavy shields, and they let out high sounds to intimidate and challenge — roars, howls, animal cries. When they had worked themselves into a fighting rage and dropped to silence at last, a loud voice lifted from behind them, calling across the field.

Agol leaned close to Oron. “What does he say? I don’t understand him.”

“It is Dasagak, the Man Eater,” Oron told him. “He knows I’m here. He says he’ll have my head before the morning is gone.”

“Then take his head instead.”

“That I’ll do. But how does he know that I am with this company?”

Horn sounds lifted behind Oron, from Maton’s lines — and an arrow flew over Oron’s head.

Startled, he reined his horse around, pulling hard.

And as he did, a man farther to the left of him, not Agol but one of the young retainers, coughed as a second arrow caught him in the chest and pushed him from his horse.

The horse bolted.

“What have you done?” another of the retainers roared at Oron — Kess, a man as young as Oron himself.

They heard the snap of more bows, a hundred of them, and the bright sky darkened.

Oron, Agol, all of them lifted their shields over their heads.

As arrow tips bit into their bucklers, another of the young men went down. His horse caught an arrow and fell onto its side. The warrior, thrown free, took two quick arrows in the side of his head, both of them entering above the left ear. The force of them pushed his eyeballs from their orbits; the wet eyes hung on his cheeks like teardrops.

Now the five dismounted and slapped their horses to be gone.

As the mounts ran free, galloping toward the far outcroppings, Oron ordered Agol to crouch beside him and the other three to put their backs against theirs.

“Why?” Kess asked again.

“They mean to trap us here,” Agol growled.

“But I’ve done nothing!” Kess complained. From under his shield, he looked at Dasagak’s restless thousand at the far end of the field.

Another round of arrows lifted and came down. They punched into the field to form a small forest of feathers between them and Maton’s lines.

A horn sounded from Maton’s formation, and then Maton yelled loudly across the wide plain, “Dasagak! He is yours! Take the wolf cub!”

Oron grunted. Crouched under his shield, he looked at Agol. “Because I killed Bodor?”

Agol sniffed. “You’re a threat to him, son, that’s all. Don’t you know that? The first thing you do is kill strong men who can challenge you. That’s what leaders do.”

“I kept such men at my side.”

“Then you’re a better man than Maton.”

“But you and these men have no reason to be killed.”

“An old man and a few pups? We don’t mean anything to anyone.”

Oron took in a deep breath, then told the four still alive with him, “Run for that mountain.” He meant the outcropping to the west — sufficiently far that they all could die trying to reach it, but surely offering a better chance at life than being caught by Dasagak’s swords.

Agol nodded and spat onto the grass.

Another round of arrows made wide sounds in the air above them and joined the forest already planted.

“But you can’t take Dasagak this way,” Agol said to Oron.

“We’ll see,” Oron told him. “He won’t kill me here. He wants to do it face to face. I’ll not die here. Now go. Stay under — ”

Gas erupted from one of the dead boys near them, the one with the arrows through his head — an abrupt sound.

Oron ordered them, “Go! Now!”

But Agol said, “Wait. Look,” and pointed toward the arrows that had landed in the earth. They were difficult to see.

Steam was lifting from the tall grass.

Oron leaned forward.

Not steam. Mist. It was green, and not rising from the grass but coming across the field from the west and filling the ground around them like a carpet.

“What is it?” Oron asked Agol.

The old man had no answer.

Oron waved at the mist with his sword; it did not disperse quickly. There was no smell to it, but it grew thicker, and very soon, within heartbeats, it had covered the men completely and cut off the sky, cut off their view of everything except one another.

Oron heard Dasagak yell across the field, “What sorcery is this, Maton?”

If Maton answered, Oron did not hear him because, from within the mist, just as Dasagak’s voice ended, Oron saw a snake move toward him, a large snake, fat and longer than —

He tried to back away.

Not a snake.

A tentacle of some kind, a vine —

It caught Oron by his legs, and when he turned to strike at it with his sword, a second vine came through the mist above his head and wrapped around his arm, preventing him from moving.

And now he was lifted into the air, into the green mist, lifted three man lengths toward the sky.

Agol called out, “Oron!” and ran toward him as Oron was pulled toward the west. Quickly.

Agol followed him.

Kess called, “Wait!” as he, too, followed, stumbling through the dense mist.

And the other two came after him.

Across the field, horns blew sharply, and the drums beat from Dasagak’s army. “What treachery is this, Maton? You lie! Your man lied to us!”

Oron, still being carried by those vines, and the men running beside him heard the powerful thunder of warriors taking the field.

Dasagak’s thousand were a storm bringing their anger to the unprepared two hundred — unprepared because Maton, in his pride, had told his sword men to keep their edges sheathed and their armor unbuckled, for this morning’s battle would be short.

Indeed, he had assured his men, there would, in fact, be no battle at all.

“Where is he?” Agol called, scuttling up a stony path as quickly as he could.

Kess and the other two were ahead of him, and the great green mist already was going, blowing east and lifting into the bright sky.

The tendrils or vines, whatever they were — nowhere to be seen.

Neither was Oron.

Until Kess, pushing through some thin trees rooted in the tough soil of the outcropping, said strongly, “Here!”

They all heard his voice, then — Oron’s growl of rage — and as Agol came up behind the younger men, he saw the Nevgan on his feet, sword out, roaring at something not to be seen.

There was movement there — a shadow, or the last piece of a vine moving away, pulling itself between small trees — and an angry Oron jumped at the movement, prepared to swipe at it with his sword.

But the movement was gone.

Oron looked over his shoulder and saw Kess, Agol, and the other two, but he said nothing. He ducked his head and prowled forward, moving past the trees, and walked up a grassy incline that led deeper into a copse.

Agol moved past the others to follow, but Kess put a gloved hand on the old man’s shoulder to arrest him. He asked, “What does it mean?”

“I don’t know.”

“This makes me cold. What kind of man is this, him and this sorcery?”

The two younger men were watching them, listening as though for clues to help them decide what to do next. Follow Oron? Go back down into the valley? What would be the purpose of that?

“It’s not his sorcery,” Agol said, and moved past Kess to follow the Nevgan.

“And Maton?” Kess asked.

Agol paused and looked behind, stared down into what he and the other three could see of the battlefield far below, through the bending branches with their leaves and past the tall rocks and stones at this height.

“He is routed,” was Agol’s opinion. “I’ll wager Maton’s head is on a stick as soon as this.” He sneered. “I fought with him and those dogs for many years. Damn him for doing this to me. Him and that right hand of his.”

“Damu?” asked one of the young men. “I never trusted him.”

“His mother slept with shadows,” Agol said, and spat a wet stream onto some nearby leaves. “He’s what came of it.” He looked at the younger man. “Nadul? Am I right?”

“Yes.”

“And you?” Agol asked the other.

“Borin. It was my grandfather’s name.”

“Stay close,” Agol advised them. “I trust the Nevgan, and this trick is not his doing. It was done to him. And by Damu or Maton or someone else — ” He looked up the grassy path. “Stay close.”

“You don’t need to tell me,” Nadul said. He was without one eye — he wore a leather patch over it — and otherwise betrayed numerous hurts for a man so young, scars and two missing fingers, and an ear that had healed awkwardly and was out of shape. Not the best of fighters, those wounds told Agol.

The other one, Borin, taller by half a head and heftier than Nadul, showed less damage and was brighter in the eyes. He could face death well, Agol reckoned — if not fearlessly, then with pride. He was a man to have with one.

Maton must have considered him a fighter of potential, perhaps a born leader.

And so to be sacrificed.

The weak ever send the strong and young to their deaths. It is how the weak keep their power.

The path led Oron into a place of tall boulders and overhanging trees with man-sized roots dug into the stones, and past those boulders was an opening, the black, cold mouth of an antre or cave, some delve.

Poking his sword before him at the shadows, he moved in, sniffing and listening.

The odor of this place was rich with the rush of damp earth and damp leaves, of roots and moss and the underearth, moist, ripeness feeding all of the growing things around. The great stones that Oron moved past were wet, almost slick with moisture, and furry with moss.

He heard a sound then but could see little ahead of him in the cave.

He moved his blade back and forth in front of him, ready for whatever might be there.

“Stop, please” — a woman’s voice.

Oron stopped. He squinted, trying to see who this was.

Shuffling — boots on the earth floor of the cave — and a face came into view, the dark-skinned, worn face of a young woman, and then the deerskin vest and skirt that she wore, and crude jewelry about her neck and waist — ropes of bone, carved and painted. Magical.

He said to the young woman, “Who are you? And why did you take me that way?”

“Warrior, I am not the one to give you answers. Swear by your mother that you will not raise that weapon against me or against my mistress.”

“Who is your mistress? Did she do this?”

“She did.”

“Then she is a witch or a sorceress, up from hell. Better that I kill her now so that she can’t hurt me further.”

“She wishes to help you if you will help her.”

Oron heard further boot steps behind him and looked over his shoulder at Agol and the young men at the mouth of the cave.

“This is for your ears alone,” the young woman told him. “Bid your companions stay.”

Agol asked Oron, “Who is she, son?”

“A witch. Or her mistress is.”

“Her name is Dia-Sust,” said the woman in deer skins. “I am Sen-Odit.”

“Southern names,” Agol said to her. “Many a way from here. Why come this far north?”

“For vengeance,” Sen-Odit replied. “And this man can assist my mistress in doing it.”

“How?” Oron asked her.

“Because of what you are.” She looked at Agol. “You are old. You have heard much in your years?”

“Aye.” Agol nodded.

“You know that this man killed his own blood-father.”

“I do.”

“Do you fear him because of that?”

“I fear no one.”

“Him you should fear,” said Sen-Odit. “This is the warrior my mistress requires.” She looked at Oron. “Will you come freely, to hear what she says, and sheathe your sword?”

From behind, Kess said, “Kill them now, Wolf. I don’t trust witches.”

Sen-Odit regarded Kess darkly but asked Oron once more, “Will you come? You know that you are unlike other fighters. You have been told this.”

“I have been told this.” Oron lifted his sword and dropped it into its scabbard. “How does Dia-Sust know it?”

“It is her way. She works with spirits. Please tell your companions to wait here.”

Oron turned to Agol. “Do it. Keep them on a leash.” He meant the other three.

“Are you sure?”

“I am. We’ll talk, Agol, when I am back.”

“Just so you do come back, Wolf.”

Oron smiled at him, and his eyes brightened, for he had been down such paths before, and in other caves such as this.

Dia-Sust must have been, once, as dark skinned as Sen-Odit, and attractive — dark eyed, full lipped, strong of limb — but she was no longer. The skin of her face now was green, a heavy green. She reclined under a thin blanket on a pallet of sticks and woven grass alongside a fire that was more hot coals than flames. A few objects were nearby — more jewelry, as well as items that Oron judged were for witch work: bowls, sticks and wands, many pieces of bone, two rolled parchments.

The knowledge that such people kept in their charmed objects and their powerful, marked stones was as strong as the ability Oron had mastered with sword work and fighting and hunting.

Sen-Odit held back as Oron came forward. He looked at the frail witch, old beyond her years, and nodded to her. “My weapon is covered,” he told her.

“Will you sit?”

Oron moved to position himself cross-legged on the ground after the manner of all tribal people at a fire.

“I sense no fear in you,” the witch said to him. “Only curiosity.”

“I have learned when fear is proper and when it is not needed,” Oron told her.

“Good. You are the man I am looking for.”

“Because I killed my father?” Oron asked.

The spirit woman told him, “This is the sign that you are a new man. This is why I brought you here.”

Oron grunted. “The vines. The ropes. I’ve waited long enough to ask you about them.”

Dia-Sust smiled, showing sharp teeth. Oron realized that she had done that to herself, filed her teeth into points, as necessary for her magic — to bite and chew living things and so take their spirits as they died.

“The vines are me, Oron,” she said to him, and lifted her blanket.

She lifted it high, and Oron saw that Dia-Sust had no arms but only vines, green ropes extending from her, at least ten of them, and all without hands. Her body itself had become as tuberous and shiny as a green young plant. She was wrapped in coils of these green vines. She had no legs or feet — she was a large plant with many vines and tubers growing from her. Those not wrapped around her stretched out on the floor beside her like undone netting.

“I have achieved this for myself,” Dia-Sust told Oron, “to accomplish what I must. Just as you killed your own father to accomplish what you must.”

Oron stared in wonder at her. “Erith and Corech . . .” he whispered, naming his gods.

“Are you prepared to listen to me now?”

Oron nodded. “I am.”

The spirit woman looked at her servant. “Sen-Odit.”

Oron heard her boot steps grow quiet as the young woman went away.

3.

The Spirit Woman

For of the soul the body form doth take:

For soul is form, and doth the body make.

— Edmund Spenser

“Damu is dead,” Oron told Dia-Sust as he sat by her fire. “None of them could have lived past the attack by Dasagak. I know Dasagak. He murders everything.”

“Only what is within his reach,” the witch corrected him. “Damu lives. As does Maton. Others, as well. They escaped when they had the chance, to fight another day. But I made certain for myself that Damu and Maton survived.”

“How? And how do I know that this is true?”

“My mist, barbarian. The mist that I sent into that field. It serves as my eyes and ears. It senses everything. It hid those two for me, and it knows now where Maton and Damu and the survivors are. They are hurrying on horses that they will beat to death.”

“If they live, then my sword wants them. I will drink their blood.”

“You will drink Maton’s blood. Damu is mine.”

“Why?” And then Oron, understanding, said, “This is why I am here.”

The plant-woman, the witch, regarded him with her slow green eyes. “A thousand ghosts surround you, barbarian. These are the ghosts of old heroes. I see lights around you like so many campfires in the night. They are like stars, like dust in the sky. These memories from old times are with you. They guide you. They pull you toward a destiny.”

“I have been told I have a destiny.”

“You have many paths to choose, but if you persevere, you may yet find these ghosts and lights fighting with you against a great evil.”

“And why do you wish to drink Damu’s blood?”

She smiled at him, baring those teeth. “Damu came with more swords than there are trees on these hills. He and his killers destroyed my people. Our wizards used magic to fight them, and many of the killers died screaming like children, but at last we were overcome, and Damu and many of those with him escaped with cattle and gold and with those of us he could sell as slaves. This was ten years ago. So my people are gone. My heart is broken. Only I remain, and this one who assists me. The father of my people bade me escape and avenge our name on this man. He said that he would protect me in the next world if I do what is necessary in this one to destroy Damu. You yourself, Nevgan, have survived such cruelty and loss. The shadows that follow me, the ghosts of my beloved people, tell me this. Are they not correct?”

Oron grunted. “My people, too, were killed by a powerful sorcerer in my home far from here.”

“And you avenged your people.”

“I killed this sorcerer.”

“And then what did you have? No people. No father. You are the No-Tribe Man.”

“This is true.”

“Nevgan, what we do echoes in the earth and is guided by the stars. We are one with all that is. Now you, without a people, with your history gone — you are free. You have no father; you are your own father now. You must create yourself. Do you understand?”

“Yes.”

“We are human. What is a human being? Here is knowledge: before we were human, we were animals. And before we were animals, we were plants. Have you heard of this?”

“No. Not even the shamans of my people claimed this.”

“Your people worshipped animal totems. But the human soul is far older than that. I know that Damu protects himself with men who are no better than animals, but he cannot protect himself from the things that were us before we became us. Look at the stars; plants observe them, as we do. Plants speak. Plants grow angry. Life abounds, and life, abounding, fights to live, whether it is plant or animal or human.

“Warrior, if I abandoned you to the plants, could you live? If the plants rose in anger and came for you, could you survive? If plants tore at you and pulled you apart the way you pull apart flowers and trees — could you continue to live as a man the way that plants would continue to live as plants? They do not speak; they listen. They do not tear and swallow; they strangle and rend. They do not stop growing. They live forever. One plant is every other plant, and all plants are the same plant. They fill the world, they stretch above us, they surround us — and you will say that they are merely plants. Can we do these things? We have paid a great price in becoming human. We are no longer plants.

“Now, Damu and his fighters will say that what surrounds them is merely plant life. Will they say that these things are merely plants when the plants suffocate them, and creep inside them, and rip the skin from their muscles and the tendons from their bones? Men will scream, and the plants will continue to tear and pull. They are plants, as I am.”

Oron sat by the fire, listening to this, watching the green woman.

“I have saved your life, Nevgan. In return,” the witch said to him, “assist me in my vengeance. I ask for a bargain. I seek a balance and wish to redress an evil done me. You, of anyone, will understand.”

“I do understand, yes.”

“I am dying. I am becoming a plant, and I am dying. I had hoped to defeat Damu by now, but I have not, and my people watch, their ghosts watch and pray for me. I sought you out, and now, here you are. Will you assist me?”

Oron told her, “I fear being touched by your sorcery if I agree to this. It can act like a powerful poison. I have seen magickers and witches die in agony with powers they could not control.”

“This is where we will assist each other. I will not harm you. Promise that you will not let others harm me. Nevgan . . . we that are human cast many shadows, in this world and in the next. We all have many shadows. I do. You do. Your shadow touches spirits in places beyond this one, just as your life touches lives beyond those only in this world. We are connected by shadows. Have you been told this?”

“No.”

“It is an ancient truth. It is shared with only a few. You are my shadow, Oron. Here is where our shadows touch. Are our lives accidental, or is there a purpose to them?”

“I have been told that there is a purpose to life.”

“And you, a new man, free to create yourself, free to make yourself into whatever you wish, born to confront evil — you have walked with shadows and are at home in the night as well as the day. Your dreams are deep. Your passions, deep. Am I not correct?”

“You are correct.”

“Your path to greatness lay on this path to my cave, Oron. If you leave now, your path is a changed one. Have I not saved your life and brought you here?”

“You have.”

“Have I not looked into your heart and seen you there, in truth?”

“You have.”

“Assist me, and you will be assured a path to great deeds. This is how the shadows join the future, and join the world to come.”

Oron nodded.

Dia-Sust said then, “The father of my people is pleased. I sense this. Your people, too, understand this new man who was born among them. We have spoken, Oron, and shared our hearts. We are each other’s shadow, and our destinies assist each other. May we both awaken now from this.”

Oron took in a breath, shook his head, and swallowed, although his throat was dry. “I have been away, and have just returned,” he said. “What did you do to me?”

“We spoke of deep matters, Nevgan. Do you remember?”

“We are here to assist each other. I am a man to make his own destiny. I have no past. I make my own past. I make my own future. I make myself.”

Dia-Sust nodded.

“I saw hints of the future,” he admitted. “A princess, or a queen. A monster. Not like Mosutha, the izhuk I killed. More powerful. Like a dragon. A darkness over the lands.”

“This is your destiny, as you are the new man of the world, yourself, and no one else’s man.”

“This is my path.”

“Yes. Assist me now, as I have asked, for I have given you this insight as a gift, as a gesture, in return for your aid.”

Oron stood. He was weary and thirsty, and his body ached, not only from the punishing fight of the night before with Bodor but also because, sitting here with this witch, his spirit had been drained, and he was made tired.

“Go,” Dia-Sust told him. “Sen-Odit has food. Dried fish. Berries. Small animals we have caught. And the water in these hills is cold and refreshing.”

But as Oron turned to go, he heard a scream from the front of the tunnel, a woman’s voice — Sen-Odit — and the men there yelling.

He hurried.

As he reached the opening of the cave, Oron stopped running. Before him, under a group of thin, tall trees, lay Sen-Odit, dead, cut through the belly. Above her stood Kess, his sword still held above the girl’s body and her blood along the length of it.

Kess was angry, and that anger was in his eyes as he looked at Oron.

The Wolf regarded Agol, to his right, and then the other two, Nadul and Borin, where they stood by a great rock.

“Why?” Oron asked Kess.

“She threatened me!”

Oron grinned. There was no humor to the grin. “A threat? This one? How?”

“She’s a witch, Nevgan! I hate things like her!”

Oron looked at Agol again. “Why did he kill her?”

“No reason,” the old man told him. “He wanted her. She’s a child. We told him to stay away from her. But he killed her to spite us.”

“Dog!” Kess spat at Agol.

“You killed her,” Borin said to Kess, “because you could. You have no honor.”

“Show me your honor!” Kess yelled back at him, and stepped over Sen-Odit’s red body. “Face me!”

But Oron drew out his own sword and with his left hand warned Borin to stay where he was. “You face me,” Oron said to Kess. “You face me. And I will kill you. Because I can.”

Kess grunted and jumped, his sword raised, intending to take advantage by speed.

But Oron met his downstroke and pushed Kess back with quick moves, step by step, with hard blows, with steel that was everywhere at the same time.

Kess lost the anger in his eyes.

Oron now saw fear there.

Kess moved to one side, then the other, and finally made a lunge to surprise the Wolf. But Oron was there, blocking him. Pushing his sword back. Pushing Kess back.

Oron brought his blade down and around and up, so that the end of it caught the wrist of Kess’s sword arm and severed it. The gloved hand, still holding the sword, dropped heavily to the ground. Oron’s blade continued upward and took Kess’s other hand through the forearm, so that the left hand, too, and the bone and muscle above it, nearly to the elbow, slipped away from Kess and landed against a tree.

Kess roared. With no hands, no hands, with only parts of both arms, he jumped at Oron, trying to stab him with the sharp bone protruding from the end of his left arm.

Oron stepped aside, lifted his sword and brought it down through Kess’s tough neck, the heavy muscle there. The body fell forward, and the sharp bone of the left arm pushed into the earth, while Kess’s head dropped near Agol’s feet.

The eyes were open, and the mouth. A hiss came from the mouth, a sigh, the noise of air.

Agol kicked the head into shrubs and green things some distance away.

Oron knelt next to Kess’s body as the blood was coming from the open neck and going into the ground. Oron cut free a length of the dead man’s woolen trousers to use to clean his sword. As he stood and wiped his steel clean of blood and gristle, he looked at the other men there.

“The first thing you do is kill strong men who can challenge you. That’s what leaders do.”

Agol told him, “You had the right, Wolf.”

Oron looked at Nadul and Borin.

“Aye,” Nadul agreed. “The choice was yours.”

Borin said, “He had no reason to hurt the child.”

Oron sheathed his sword, but as the steel settled in its scabbard, a noise came from the cave mouth behind him, so that he bared his weapon again as he turned, kneeling in a defensive posture.

Dia-Sust was there. Not all of her, but four of her tendrils or vines, her arms.

Agol asked Oron, “What is in there, Wolf?”

Oron sheathed his sword again, understanding what was needed. “Wisdom,” he told the old man. “Wisdom, of a kind.” He approached Sen-Odit’s corpse, knelt and lifted her, and carried the body to the opening of the cave.

The tendrils rose, the ends of them touching the body.

Oron held the corpse out, and tendrils wrapped around it, took the body from him, and carried it back with them into the darkness of the cave.

There was silence. All of them there let their blood calm, let their anger and fear settle.

The tendrils returned, six of them, reaching out of the dark cave and almost touching Oron’s chest.

He understood and backed away until he was at Kess’s corpse. He removed the man’s boots, then dragged the headless body toward the tentacles.

None of the other three said anything.

The tentacles came down, scraping on the grass and stones, and wrapped around Kess’s body and lifted it back into the darkness.

Oron retrieved Kess’s head; holding it by its hair, he lobbed it into the cave. It landed with a noise and rolled farther into the shadows.

Soon enough, from within those deep shadows, other sounds came to the four of them — moist sounds, sucking noises, something being eaten, and something doing the eating.

It was Dia-Sust doing what she must, Oron knew, eating Sen-Odit’s body and Kess’s, or draining them to stay alive. Doing what was necessary.

Agol shook his head. “Wisdom?” he asked Oron.

Oron didn’t answer; he shrugged. Then he moved toward the small trees around them to collect matter to build a fire.

Nadul retrieved Kess’s boots. They fit him well and so replaced his old, worn pair, which had been giving him blisters.

4.

The Search

I have no other image of the world except those of evanescence and brutality, vanity and rage, nothingness, useless hatred…vain and sordid fury, cries suddenly stifled by silence, shadows engulfed forever in the night.

— Eugene Ionesco

“Lorsque j’écris….”

Just inside the cave, Oron and the others made a small fire, and there they sat, eating berries and some of the meat that the witch and her friend had caught. Initially, Agol and Borin and Nadul were uncertain about eating the witch’s food — who knew what kind of meat it was, in fact, or what it might do to them? But Oron, as hungry as he was, put away many swallows and came to no visible hurt, and finally their own hunger made the others join him.

They gathered water from a cold stream that Borin found down one side of the height where they were, and every one of them filled his skin. They were silent as they ate and drank until their bellies were full. Agol burped; that brought a laugh from Borin, and his grinning eased the tension among the four of them so that, at last, Nadul asked Oron, “What is in there? The thing with the vines?”

He told them about Dia-Sust, what had happened to her and what she had become, made herself into. He told them that she had, by a magical kind of sight, discovered Oron and sensed that, because he himself had endured the same loss — his people being destroyed by a powerful evil man — and because he had managed to destroy that man, a sorcerer, in revenge, Oron could help her, as well. This is why she had saved him on the field. She had kept Damu and Maton alive, as well. Tonight, they were still running away with other men of their company who had survived with them. Dia-Sust wished to kill Damu; Oron was free to confront Maton. However, she was not a true woman any longer. She had used sorcery to change herself into something more plant than woman.

“You, Nadul and Borin, and you, Agol . . . this is not your matter if you don’t wish to continue. But I’m convinced that my path is designed to join this woman’s. Kess’s killing her servant settled it for me. And she has kept me alive to kill Maton and to meet Dasagak, my enemy, on another day. So my path is set. But you may do what you will. I don’t expect you to fight my fight with me.”

Agol said nothing; he stood and placed a hand on Oron’s shoulder as a father or uncle will do to a young man, reassuring him, then went outside to sit under the clouded stars.

Nadul and Borin spoke between themselves, and Oron listened as they made their decision.

“We would have been dead on the field, either by Maton’s arrows or by perhaps by Dasagak’s killers,” Borin said. “One left us to die, the other wished only to kill us and take what we own. Now, here we are with you and this witch who has kept you alive. Our chance is better with you, Oron, and with this strange woman. We feel that you are a man of honor, and honest, and I think you are a good leader, as well.”

Oron smiled at them both; anyone used to hardship and a lonely life spent on the edge of things would have agreed with them. Some of us know no other way. Oron thanked them and assured them that they could sleep safely here at the mouth of Dia-Sust’s cave. Surely she, too, now knew that these hardened young men would assist her, as well.

Then Oron went outside. While the younger men sat by the fire, then stretched out to rest, Oron talked in a low voice with the veteran of many conflicts and a veteran, as well, of much that life accords us.

After an agreeable moment looking at the stars and enjoying the sight of the forest at night, quiet and full of life as it was, Oron said, “Her gifts are powerful.”

“They are,” Agol confirmed.

“Nadul and Borin will come with me. And you?”

“Of course,” Agol said. “They have made a wise decision. I’ll keep my eye on them. They want women and money. They have nothing else in life. This will educate them.”

Oron told the old man, “She says, Agol, that before we were men, we were animals, and before even that, we were plants, which is the source of her magic. Have you ever heard of this?”

“No. But the world is full of those who sense deep things and talk to the gods. It’s not my way. But surely the powerful earth is full of such mysteries, and she has communicated with some of them.”

“I was also told by her that I have a destiny.”

“That may be. I have tried all my life to understand the sense and order in what the gods do. It is beyond me, Wolf. They play with us, but it is serious play. And they never quite tell us enough for us to know what they are about.”

Oron agreed with that. “But,” he admitted, “I don’t feel it in me.”

“Still,” Agol told him, “inside every god is a mortal man. Is this not said? And inside every man is a god. If your destiny is planned, they’ll give you signs.”

“This witch is such a sign. I trust her, Agol. And by doing this, I will one day take Dasagak’s head, as well.”

“No doubt.”

Oron confided to Agol then, “She says I am to fight a great evil one day.”

“Not Maton?” Agol asked. “Not Dasagak? They’re only men.”

“Something else. I sensed it but could not name it. She says that I am a new kind of man because I killed my father. It marks me. But in the eyes of the gods, it is not a crime. It is something else.”

Agol asked him, “Why did you do it? I’ve never heard of such a thing before.”

“He was drunk, and he wished to take the woman I was with. I didn’t set out to kill him, but he forced it.”

“You could have walked away.”

“But I didn’t.”

“Perhaps the evil you’ll fight is also something you can’t walk away from,” Agol said. “It would be a proud destiny, to fight a great evil.”

“She says we are each other’s shadow. I help her, and she helps me.”

“Our shadows and spirits can have lives of their own. It is of the gods, and beyond me, as I say. But I have not known any other young man like you, Wolf. If anyone has a destiny, then you are the man.”

“I won’t lead you into death if I can prevent it, Agol.”

“I know that. That’s why I’m here. Fortune — or destiny — is with you.”

Oron said, “Right now, I wish only to have Maton’s head. And the witch will need me, now that the girl is dead.” He stood then. “I’ll sleep by the fire with Nadul and Borin.”

“I’ll be there shortly. I like to look at the stars.”

Oron asked him, “Do you think our destiny is in the stars? Many say that.”

“I think our destiny is in our own hearts. But the stars watch. And we amuse the gods.”

In the morning, when Oron awoke and stepped away from the others sleeping at the cave mouth to relieve himself in the undergrowth nearby, he heard horses whinnying. He didn’t wait until he had urinated to investigate. With a full bladder, he moved toward the sounds and saw, on the other side of some lean trees near where he had killed Borin, five horses, those he and the others had released the morning before when they were under Maton’s arrows.

Surely Dia-Sust had managed to bring them here.

Once he had emptied himself, Oron returned to the others, who were now awakening, and went past them into the cave. He called out to the witch so that she would know that he was the intruder (although surely she could sense it) and asked her about the animals.

“I followed them, yes,” she told the Wolf. “I created breezes to urge them here for you. And for me, Oron. You must create a bed to carry me on. Attach it behind one of them.”

“I understand. We’ll do it now.”

“I will give you the directions. Begin by returning down this mountain and across the battlefield.”

He looked at her eyes, the glow of them in the shadows of the cave, then returned outside, where the others were eating what they had not put down the night before, and also gathering some berries, and drinking water.

Oron with his sword began cutting away saplings and stripping them of their branches. When he had two long poles, he lashed them together at one end by securing them with strips of bark and lengths of tough grass. Then he used a third pole to hold the opposite ends apart, wide enough to accommodate the spirit woman.

As the others finished their meals, they assisted in tearing strips of bark from trees and weaving lengths of grass into netting that they stretched across the wide, triangular end of their construction. When they were finished, they had a small frame or sled that could easily be pulled by one of the horses down the outcropping and onto the field.

This done, Oron went into the cave and shortly returned carrying Dia-Sust. Only her head and face were visible; the remainder of her was covered in her old blanket. She was no larger than an adolescent, but the swelling of her beneath her covering gave her the appearance of being a great, swollen bladder with a human head, a green human head.

There was no need to secure her to the sled with strips of bark or grass. The woman’s own tendrils wrapped through the netting and around the poles to keep her comfortably in place.

The four mounted their horses and began moving in a single file down the mountainside toward the low valley. Oron led the way, with Agol behind him, then Dia-Sust, her horse led by Agol, followed by Nadul and Borin.

Borin, watching the sled and its passenger as it bounced over stones and large roots, said, “I notice that the horses are not frightened.”

Dia-Sust twisted her head to look up at him. She did this without effort, although it would have strained or injured anyone else attempting it. She asked Borin, “Does this frighten you?”

He told her, “I’m not afraid yet. But I wonder that the animals are not concerned.”

“I am no threat to them,” Dia-Sust told him. “I am a plant. I am vegetation. What reason do the horses have to fear vegetation?”

On the field, tens of bodies were scattered, singly or in lonely groups, fallen where arrows, spears, and sharp edges had cut them down. The younger men moved their horses in wide paths to see whether any good pickings remained on the corpses, although their mounts were shy in the presence of so much death.

Agol, leading Dia-Sust’s horse, and Oron moved toward the southern edge of the field, where the bodies were more numerous. It was clear that Maton’s hundreds had broken in this direction, chased by Dasagak’s army, and had been taken in great numbers, for the dead were in piles, and the crows and wild dogs were still busy picking at whatever remained exposed.

Oron slowed his horse and held still until Agol and the witch were alongside him. He asked Dia-Sust, “We continue south?”

“Yes. They are not far ahead of us. They see to their wounds.”

Agol leaned back in his saddle and told her, “We came this way. There is a lake ahead, and trees and water. A falls.”

“I saw these things,” Dia-Sust said. “It is where they are.”

Agol looked at Oron, and they nodded to each other, both of them of the same mind, to circle west, keeping in the forest that was there, and taking a path that led upward as the land steepened, so that they would be near the height of the waterfall, which would give them an advantage. And the sound of the dropping waters would obscure the noise they made as they approached.

When Nadul and Borin reached them, Oron told them of his plan. The two had found nothing of value left on the bodies of their dead companions; Dasagak’s army had taken anything worth having or trading.

The sun was climbing in the morning sky, behind clouds that might bring rain later on, as the five moved into the rocks and trees to the west. And as they entered the cool forest, as the clouds were hidden beyond the height of tall trees, and as Oron listened to the horses’ hooves moving over earth and roots and to the sound of the witch’s sled as it was pulled across the flesh of this land, he regarded everything around him with new senses. He knew that the world is a living thing, but Dia-Sust’s comments had enriched his measure of that.

He watched the shadows around them, the deepness of the forest, the waving of leaves, and the soft moss on fallen trunks, the cool dew on spiders’ webs and animal nests tucked away in silent corners, and he began to have the sense of an awakening, as though the new man within him, or the god within him, shared more of this world than he had previously realized.

What must life contain, all of life, if a poor woman from a broken tribe could magic herself into a plant, another kind of living thing, and see with mist and smoke as though with eyes? What must life be if an important event awaited Oron himself one day, a destiny to fight great evil, to confront a monster empowered by the earth and stars to challenge the Wolf himself? Where was this evil now? Resting? Sleeping? Forming? Growing into its evil as Dia-Sust was growing into a plant?

What must life contain, all of life, and what must life be, if such things as these filled out the world beyond people and their limited sensations and hungers?

Your people worshipped animal totems. But the human soul is far older than that. We have paid a great price in becoming human.

When the sun was nearly as high as it reached at midday, the four men dismounted and tethered their horses by a cool stream that came down from rocks above them, surely an arm of the same waterfall they were approaching. Dia-Sust rested with closed eyes in her hammock while the others took out what food remained in their belts, filled their skins once more with good water, and searched nearby for nuts or berries or roots to add to the dried meat they had.

Oron was seated beside the witch and was about to say something to her when, looking at her, he saw her open her eyes in fright and warn him, “Oron!”

The warning was not for him. Just as she said his name, the leaves behind Borin made noise, and then Borin groaned, lunged forward from where he had been sitting, and kneeled on the ground. A long shaft, a spear with a bronze point, struck the ground before him as blood poured out strongly from his great left shoulder.

Immediately Oron was up, his sword out, and charging toward the bushes behind Borin.

But Agol, who had been seated closer to Nadul and Borin than the Wolf, was the first to move, crouching, into that wild green growth, steel out, eyes alert for whatever was there.

Just as Oron was approaching behind him, Agol raised his sword and brought it down. The edge cut through branches and leaves and brought up a man’s cry. Agol leaned into the brush, grabbed hold of something, swore mightily, and pulled out the intruder.

He was one of the younger rogues of what had been Maton’s company. He had not even moved his sword from his side to defend himself; he was slow. Agol’s steel had caught him along the right elbow and forearm, and the blood was dripping quickly.

As the young man stumbled forward, Agol pushed him onto the ground in the middle of the small campsite.

Holding his wounded arm, the youth rolled onto his back, spat at Agol — and then saw the witch close by him.

“Gods!” He moved away with terror in his eyes as Dia-Sust lifted her cover with two snaky green arms and held the ends toward him.

Oron walked over to him, placed a boot on his chest, and pushed the frightened youth again onto his back. “You’re one of Maton’s,” he said. “Where is he?”

“Far away.”

“Not so far. Are they by the river?”

“Go to hell, Wolf.”

Oron lifted his boot from the chest and brought it down hard on the wounded arm.

The young man growled and moaned.

Oron asked him, “How many with him? How many left?”

“Ten and eight. No more than that.”

“By the river?”

“Yes.”

“Not by the waterfall?”

He shook his head and looked at Dia-Sust. “What is that? What have you done?”

Oron did not answer him. Instead, he asked, “Why attack us?”

“To take what you have.”

“Alone?”

“I can kill four men.”

“You can’t even kill one man.” Oron swiveled to look at Borin, who was standing now with Nadul beside him.

Nadul, having examined the long slice of the wound, said to Borin, “Not so deep. A bit to the right, and all of your blood would now be on the ground.”

Borin grunted. His gods had guided the spear this time.

Agol was waiting with strips of cloth he carried under his shirt; the years had taught him to ride with many different tools available for just such reasons as this. Now he bound Borin’s wounded shoulder, covering it first with leaves he found that he knew would help ease the pain, then wrapping them with the cloth.

When he was done, Oron asked Borin, “Do you want the kill?”

Borin nodded and stepped forward, pulling out his sword.

As he stood above his attacker, the youth asked him, “What is that?” — meaning Dia-Sust.

“She’s the witch that’s going to eat you when you’re dead.” Borin lifted his sword.

The youth said to him, “Tell the gods my name! My father — ”

But the end of Borin’s sword already had creased the front of the young man’s throat so that he gagged, the blood came, and he was dead.

Dia-Sust now said to Oron, “You must do that to me, Nevgan.”

“Do what?”

“I am nearly dead. I can no longer control my limbs. I am too weak.”

“What must I do?” He looked down at her as the other three men approached behind him, concerned.

“Sever my head and leave the rest of me here. Wrap my head in this blanket. Cut off this dead man’s arms. They will give me strength. I will grow new limbs.”

Agol stepped up beside Oron and said to the witch, “I wouldn’t risk it, woman.”

“Old man, I know what I am about. This is how I will survive to kill Damu. Don’t you think I’ve done this before?”

Oron took out his sword and stepped forward, kneeling to do it.

Late that afternoon, when they had nearly reached the top of the height their horses were climbing, the four took their rest again. The day’s shadows were long, now, and the sun nearly gone, hidden as it was behind clouds and the tall trees. A drizzle had begun, and the air was damp.

“Tonight,” Oron said. “I’ll climb ahead to see where they are. Then we’ll know.”

“Wolf, I’ll do it,” Nadul said.

“Can we trust you?”

Nadul smiled. “I am more silent than air.” He stood then and went off into the forest, and he was indeed so quiet that none of them heard him go.

The three sat quietly then and kept their eyes on the blanket in which Dia-Sust was wrapped. It had not moved in some time; Oron wondered if she had, in fact, died at last. Neither had they heard any sounds coming from her. He wondered what that meant, if perhaps she were indeed growing and changing like some bud before it blossoms, or the silent root as it grows under the earth.

The blanket quivered, and part of an arm dropped out, a clot of meat that had gone dry or been drained.

Following it came a glistening shoot, a fibril or white tendril, as young and clean as something in springtime. It retrieved the meat, curling around it, and pulled it back beneath the blanket.

Agol coughed, seeing this, then stood and went into the trees to empty himself.

When he came back, Nadul was with him. They sat on stones, and Nadual said, “Eighteen of them, as he said. At the bottom of the falls.”

Oron grinned, stood, and walked to his horse to lead them the rest of the way.

5.

The New Man

The power which resides in him is new in nature, and none but he knows what that is which he can do…

— Emerson

The moon had not yet risen, and the night around them was fully dark, when Oron ordered the men with him to dismount and go up the steepness afoot. He did not wish to endanger their animals and, in any event, the three could proceed more quietly without them. They tethered the horses to some birch trees and continued on.

Oron carried Dia-Sust’s head bundled in the blanket. He kept it by his side, tied to his leather belt, so that the thing bounced against his left thigh. And it was wet. Whatever sorcery Dia-Sust was concocting, it seeped through the cloth of the blanket and wet Oron’s trousers. But the substance did not burn, and he heard little noise from the head. Only once did he ask the thing, whispering to it, “Are you alive?”

His answer was a shuddering of the bundle and a few syllables that might have been words, but that was all.

After a time, the men heard the sound of the waterfall to their left as moonlight broke through the tall foliage above them, and they heard other sounds, too, from the direction of the water. Someone or something moving.

Oron reached for the weapon at his side, but not quickly enough. A sharp point caught him along the left forearm, cutting him and warning him away from his sword hilt.

More spear points came toward the others with him, and Agol warned the two younger men, “Hold off! We know them!”

Six men of their former company came ahead, some of them with bandaged wounds, all holding Oron and his three at spear point and sword end. By the light of the moon, clean as it was and bright as it rested on sweating faces and tense, muscled arms, the six regarded Oron and the others as they might a wolf pack.

Oron lifted his head and said to the foremost of them, “Thon, where is Maton?”

“Close by, Nevgan. He suspected that you still lived.” He called behind him, into the brush, “Damu! Here!”

The bundle at Oron’s side quivered, and it seeped more liquid.

In a moment, the leaves behind the six parted and Damu, with two others, came through. “The Wolf,” he said.

Oron told him, “I’m not surprised that you lived. Still having others fight your fights?”

“Insult me if you like, but I’m taking you to Maton.”

“Good. I can kill him quick, then get some sleep.”

Damu noticed the round, wet satchel hanging from Oron’s belt. “What is that? You stole from the corpses on the field?”

“It’s the head of an enemy.”

“Is it?”

“I took it just tonight.”

“Nevgans collect heads now, like other savages?”

“Only this one.”

“Come.” Damu stepped back and gestured for those with him to move Oron and the others forward. “And take their swords. Take their knives.”

Oron and Agol, Nadul and Borin reluctantly unsheathed their steel and, grumbling, surrendered their weapons.

“Thon,” Agol said to that one, “I saved your life only three moons ago.”

“You did, old man. And I am grateful. Now give me your blades.”

As they were pushed ahead, warned to move slowly and not attempt escape into the dark forest around them, Oron felt the trees on all sides move with more than the wind.

Did any of the others sense it?

Clearly not. Perhaps he was open to the sensation because Dia-Sust’s head was bouncing against his thigh and she could share her thoughts with him by reason of that.

Perhaps he was indeed the only one of them who noticed branches and leaves twisting strongly, as though with intent, and not simply because they were touched by the night wind.

The witch had indeed created a powerful magic.

They came to something like a clearing, an area where the trees thinned and gave upon boulders contained by man-sized roots and other growth. The moon opened above them, startling in its brightness, and Oron and his three saw Maton sitting on a rock with what remained of his killers, no more than eight others, now, most of them bearing hurts from battle, some with bruised faces, others with arms or legs wrapped in clothes stripped from the recently dead. Beyond them was the river, not large, fed by the waterfall to the south.

Maton grunted as he stood and said to Oron, “I should have killed you outright. How did you survive? You escaped in the fog.”

“I did.”

“And what sorcery of yours was that?”

“Not my sorcery, but sorcery it was.”

“Sent by Dasagak?”

“You should have asked him — before you ran away.”

Maton looked at the three standing beside the Wolf. “I’m missing another of my men,” he said. “Did you kill him, too?”

“We did,” Oron told him. “My company and I.”

“Your company?”

“Aye.” Oron undid the satchel at his side and held it in his right hand.

“More sorcery?” Maton asked.

“It is sorcery,” the Wolf told him. “That fog was sent by a witch with the powers of the earth in her. This is her magic.” He held up the bag. “But not for you.”

“Then who?”

Oron looked at Damu, who was only a short distance from his captain. “That one. Your guard dog.”

Damu sneered.

“You killed a people southway of here.”

“I killed many, Nevgan, in every direction under the sky.”

“You awoke an angry spirit, Damu. This is for you.”

“What is it?”

Oron cast the satchel onto the flat ground between himself and Damu. The wet blanket unrolled and from it, under the bright moonlight, came the head of Dia-Sust — yet now a head no longer. It was a green-brown knot with two yellow eyes, not human, and from it sprouted six, eight, ten branches, thin and wet, to push the knot of her head higher than a man’s height.

Every one of the killers there lost his air, stopped breathing.

Damu fell back and reached for his sword.

But Dia-Sust, now a tall, spidery thing, reached for him with three of her branches. They had no hands on them, only points at the ends of them, and one of them took Damu high through the stomach, just below his breast bone, and lifted him from the ground.

“Witch!” Damu growled, as blood came from his mouth. He tried to hurt the sorceress with his sword, and he managed to graze one of the brown appendages near him, but then the end of that branch shot through his shoulder and, pushing hard, tore the arm from the body.

Maton, below, removed his sword, crouched, and yelled at Oron on the other side of the clearing, “What sorcery is this, Nevgan?”

Oron laughed out loud.

As Damu’s arm fell to the ground, the thing shook him back and forth just above the heads of the men all around. His blood sprayed everywhere, and Maton’s fighters held up their hands to avoid being blinded by the red drops.

Damu’s bad left leg, the one nearly lost years earlier, came free, and its wooden crutch. He began to scream. Where did he find the strength? He was choking with blood, but still he screamed.

Two more arms, branches, pushed through his body, one at his neck, the other near his crotch, and shook his body so terribly that it was finally torn apart, the head dropping and rolling away, the torso itself pulled into halves with the organs of it spilling out, raising steam in the cold night air.

Still Damu screamed.

His organs and blood, his entrails on the wet ground, screamed, and his head. The entrails of him moved on their own as though they were fat, living worms, and in flexing and rolling on the grass and stones of the clearing, they issued wheezing sounds, perhaps echoes of Damu’s howling spirit far below ground or in whatever hell awaits such men.

Now Dia-Sust, the thing, the spidery monster, used her ten branches to smash the pieces of Damu’s body further, pushing his face apart to break the bones beneath, disarticulating his spine and his arms and legs, so that what remained was gore, merely meat and organs, with nothing left to show that these might once have been contained within someone alive.

The manner in which he had left Dia-Sust’s southern village, burned to the ground, torn in every direction, with the pieces scattered, stones and lengths of wood, bundles of grass left to blow away in the wind, whatever remained — this was how she now left Damu, in pieces, with nothing left of him to show that he had ever been, with whatever remained left to sink into the earth or be carried away by dogs or be eaten by the worms and insects that live by such raw pieces.

“Oron!” Maton howled it, yanked his sword from its sheath, and moved toward the Wolf, taking care not to step in the blood and gore on the ground.

He had no wish to be contaminated by such sorcery.

Oron turned to Thon. “Give me my sword!”

“Give it to him!” Maton commanded.

Thon took it from a man near him and handed it to Oron.

Oron stepped ahead, moving into the center of the clearing, reckoning how best to meet Maton in his anger.

But Maton stopped several lengths away, moved his sword from his right hand to his left, and removed his barbed chain belt. He swung it around his head, with the heavy spiked ball on the end of it moving in a wheel.

Oron said to him, “You won’t even meet me with your sword!”

Maton laughed and came ahead, prepared to tear the Wolf open.

But then he screamed in pain.

The ball was caught in the branch of a leaning tree.

Not Dia-Sust —

“The tree moved!” Thon yelled.

— but one of the tall birches nearby. It had reached with its branches, as though they were arms, and caught Maton’s weapon as he whirled it, tearing it from his hand and sending a painful shock up his arm and shoulder.

Oron looked at Dia-Sust, the thing, the spider.

But she was already moving away.

Painful though his right arm was, Maton took his sword hilt in that hand and jumped toward Oron. “With my blade, then!” he said strongly.

Oron moved forward to meet him while the brilliant moon continued to brighten the clearing as though it were midday — and while the trees nearby, all around them, swayed, moved their branches and leaves, leaned in toward the fighting men — observed.

“You’re full of surprises, Nevgan,” Maton grunted.

Then he came in, swinging his long blade, forcing his way past Oron’s guard and slicing the younger man along his right shoulder.

Oron cursed.

“More blood for your witch!” Maton spat.

But Oron circled to his left, held off several of Maton’s strokes, then abruptly charged in, forcing the old dog back.

Agol, from where he stood, hooted out loud. “Do it, son!”

And kept at it. So that Maton, moving away, stepping backward as he searched for an opening, slipped on what remained of Damu, the gore on the stones, the wet blood.

He came down on his right side into the blood and the long stretch of entrails. Unable to use his sword, he tried to roll free and avoid Oron. But the Nevgan’s steel caught Maton cleanly on the left collar bone, broke it, and sliced through his leather armor and his chest to come out low on the captain’s right side.

Maton howled as what had been inside him squeezed out and was exposed in the moonlight to every man there.

He panted for a long time as he bled. The meat of him, where he had been opened, glistened and continued to push free of the wet leather of his harness. Maton moaned and moved his legs from one side to the other, back and forth, but at last he gave out.

Oron breathed deeply, pulling in the cold air with the smells of death in it, blood and the rawness of killing and cutting. He looked over toward Agol as the old veteran said to him, “Wolf.”

Agol pointed toward where Dia-Sust had been.

She was gone now, or nearly so. She had been pulled into the trees nearby. The trees had reached for her and taken her into them, lifted her into their branches to hold her there, where she must die, although she had not been born as one of them.

Oron regarded the blood and gristle on his sword, walked in a small circle to get his air back, and surveyed what remained of two men on the stones and grass of the clearing.

The moon went behind clouds.

He looked at the trees that had taken the witch.

“We that are human cast many shadows. We are connected by shadows. Are our lives accidental, or is there a purpose to them?”

He regarded Maton’s company and said coldly to those men, “I am Oron. I killed my own father, and I’ll kill anyone else who deserves it. Do you understand?”

No one answered him until Thon came ahead, nodded, and replied, “We understand, Wolf.”

“I made a pact with that witch, and I’ll do it with anyone or anything else that brings me what I want. I’ll do it with you dogs if you still want what we started for. Or do I ride alone?”

One of them, not Thon but a man bigger than he and with scars to boast of, told Oron, “I am with you, Nevgan.”

A second came forward then, and a third, and Thon also stepped forward.

“I’m with you, Wolf.”

“And I.”

“And I.”

Oron lifted his right hand to them, a gesture of comradeship, despite the pain in his shoulder. He regarded Agol and the other two, Borin and Nadul. The two younger men ducked their heads and put their fists to their foreheads. We follow you.

Agol told the Wolf, “You’ve earned them, Captain.”

“Aye,” Oron said. “I have. Tomorrow, then,” he promised his company, “I’ll take you over those hills to women and plunder. This is our way, and anyone who joins us may have the same. Anyone against us takes what we give them!”

Loud hurrahs and shouts of agreement met his announcement.

“Now . . . let me sleep!”

Thon and Agol, Nadul and Borin slapped their chests as Oron went past them and found a place just inside the wood line to rest for the remainder of the night.

Agol and the two younger men settled themselves close by to guard the Wolf, keeping a watch for him through the night.

As he closed his eyes, Oron sensed movement in the trees above him.

He looked up.

Leaves and branches tossed gently in the night.

The wind moved them.

The wind — and something else.

The trees, too, would watch over him as he slept.

About “The Shadow of Dia-Sust”

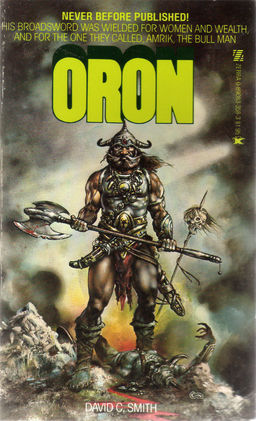

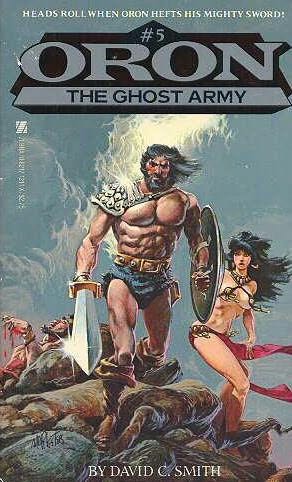

In late 2011, I was invited by Bob Price to write a new story featuring my character Oron as part of a planned anthology of sword-and-sorcery stories. A number of other authors who had written s&s back in the Silver Age of the 1970s and early 1980s were invited, as well — Ted C. Rypel and Adrian Cole and, I think, Keith Taylor, along with others. This would have been an exceptional showcase of talent — much good work from those of us who, as young men, had promised to produce a new generation’s worth of intelligent masculine fiction; however, commercial publishing in the mid 1980s rerouted the fantasy genre away from mythic adventure stories into amplified fanfic epics concerned with thrones and wheels.

In late 2011, I was invited by Bob Price to write a new story featuring my character Oron as part of a planned anthology of sword-and-sorcery stories. A number of other authors who had written s&s back in the Silver Age of the 1970s and early 1980s were invited, as well — Ted C. Rypel and Adrian Cole and, I think, Keith Taylor, along with others. This would have been an exceptional showcase of talent — much good work from those of us who, as young men, had promised to produce a new generation’s worth of intelligent masculine fiction; however, commercial publishing in the mid 1980s rerouted the fantasy genre away from mythic adventure stories into amplified fanfic epics concerned with thrones and wheels.