The Shout of a Young Man Who Finds the World a Complicated Place: The Eternal Champion by Michael Moorcock

When I was a kid, all my friends read Michael Moorcock’s sprawling Eternal Champion series. Endlessly resurrected and reincarnated, the Eternal Champion exists to right the balance between Law and Chaos. According to Moorcock in the introduction to the 1994 edition of the novel, The Eternal Champion:

When I was a kid, all my friends read Michael Moorcock’s sprawling Eternal Champion series. Endlessly resurrected and reincarnated, the Eternal Champion exists to right the balance between Law and Chaos. According to Moorcock in the introduction to the 1994 edition of the novel, The Eternal Champion:

I use the ideas of Law and Chaos precisely because I am suspicious of simplistic notions of good and evil. In my multiverse, Law and Chaos are both legitimate ways of interpreting and defining experience. Ideally, the Cosmic Balance keeps both sides in equilibrium. By playing “the Game of Time”… the various participants maintain that equilibrium. When the scales tip too far toward Law we move toward rigid orthodoxy and social sterility, a form of decadence. When Chaos is uppermost we move too far towards undisciplined and destructive creativity.

Seemingly deep stuff for teenagers to be reading, but I think it was part of the series’ appeal. Teenagers are constantly pushing boundaries and trying to get a grip on right and wrong. I think many of them are as suspicious of supposedly “simplistic notions of good and evil” as Moorcock was. It appeared to be presenting a more nuanced way of looking at the world.

Most of the guys (and it was all guys) I knew who read swords & sorcery back in the 1970s and early ’80s were SF/F geeks, potheads, or metalheads and there was a lot of overlap amongst those groups. In my experience, gaming had a lot to do with bringing those tribes together and we all loved Moorcock’s stories and heroes.

Most preferred the morose albino, Elric, of doomed Melniboné. Dressed in black armor, wielding the evil soul-drinking sword Stormbringer, and riding a dragon — I totally get it. A few liked Dorian Hawkmoon von Koln and his adventures across post-apocalyptic Europe and America better. Personally, I did and still do enjoy the two trilogies about Corum Jhaelen Irsei, last of the Vadhagh. Steeped in Irish myth and a gloomy Celtic miasma, I think they’re the most intense and beautiful books in the series.

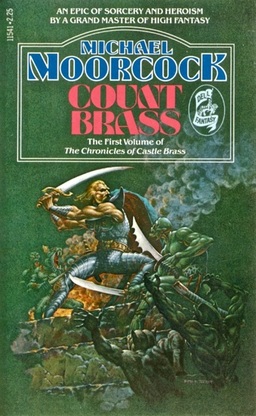

Whichever champion we liked best didn’t matter, though. Everybody seemed to read every book they could get their hands on. I remember the giddy excitement when my buddy Alex and I finally found copies of Count Brass, The Champion of Garathorm, and The Quest for Tanelorn in a Barnes & Noble in Manhattan. Moorcock’s books — moody heroes, thrilling action, and gaudy, often grotesque, worlds — seemed perfectly written to a teenage male audience.

Whichever champion we liked best didn’t matter, though. Everybody seemed to read every book they could get their hands on. I remember the giddy excitement when my buddy Alex and I finally found copies of Count Brass, The Champion of Garathorm, and The Quest for Tanelorn in a Barnes & Noble in Manhattan. Moorcock’s books — moody heroes, thrilling action, and gaudy, often grotesque, worlds — seemed perfectly written to a teenage male audience.

Moorcock’s heroes are rebels and dreamers, unsuited to the worlds they live in. They experience big, explosive emotions and wreak terrible destruction on their enemies. Whether they want to or not, they lead lives of great danger and adventure. Even if they don’t always get to keep it, they all seem to win the love of the most beautiful women in the world. Oh, and the fate of creation always hangs on their shoulders. What they do makes or breaks whole dimensions of the multiverse.

These books, much more than The Lord of the Rings, were the common text my friends and I drew on when we first started roleplaying in the late ’70s. Many worlds were destroyed a la Moorcock in the basement during those heady early days of gaming on my block. There are no long books in the series. All are short, sharp shocks of sword & sorcery action, filled with fantastic creatures (Quick – what’s your favorite Moorcock creation? The Grahluks and the Elenoins? The giant flamingos? Whiskers?) and mindblowing battles raging across time and space. Who wants to put some heir on the throne when you can summon up gods and demons and change the destiny of the universe?

Moorcock started dreaming up the Eternal Champion stories and heroes when he himself was still a teenager. Erekosë, protagonist of The Eternal Champion, first materialized on the page in the mid-’50s. In 1962, The Eternal Champion was published as a novella for the magazine Science Fantasy and was brought to novel-length in 1970.

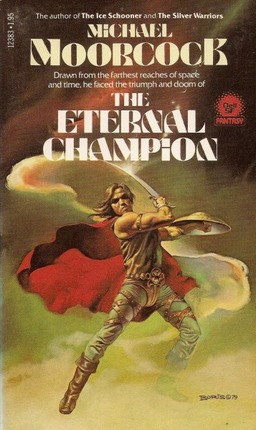

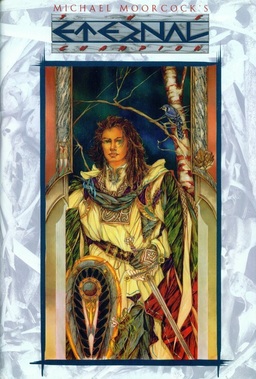

As often as I’ve gone back to Elric, Corum, and Hawkmoon, The Eternal Champion is one novel in the series I hadn’t touched since first reading it nearly thirty-five years ago. Seeing the dynamic Boris cover a few days ago while scanning the ‘net was enough to make me dust off the (unread) omnibus edition of the Erekosë stories put out by White Wolf twenty years ago as part of their fifteen volume Eternal Champion series.

As a novel, The Eternal Champion is a bit thin. John Daker is an academic in our world who dreams of voices calling him Erekosë and begging his help. Eventually he is transported to another place and learns that in ancient times Erekosë saved humanity from the devilish Eldren, a race inimical to mankind’s mere existence.

I looked up. I stood before them in the flesh. I was their god and I had returned.

“I have come,” I said. “I am here, King Rigenos. I have left nothing worthwhile behind me, but do not let me regret that leaving.”

“You will not regret it, Champion.” He was pale, exhilarated, smiling. I looked at Iolinda, who dropped her eyes modestly and then, as if against her will, raised them again to regard me. I turned to the dais on my right.

“My sword,” I said, reaching for it.

I heard King Rigenos sigh with satisfaction.

“They are doomed now, the dogs,” he said.

The minor characters never take on more than a dimension or two. King Rigenos is a gentleman, until he talks of the Eldren, and his daughter, Iolinda, is beautiful. There’s the distrustful Captain Katorn and the friendly Count Roldero. On the other side is the noble Eldren lord, Arjav, and his enchanting sister, Ermizhad. They each have a role in the script, a specific part to play in the unfolding drama set before the once and future hero, Erekosë.

The only solution, claims the king and his advisors, is a final one. The Eldren, the Hounds of Evil, must be wiped away from the face of the world. But all, as one may expect, is not what it seems.

There are very few surprises in The Eternal Champion and Moorcock admits it’s “not one of his ambitious books.” Perhaps it isn’t, but it does lay the foundation stones for much of what would come later in books like the Elric novel, Stormbringer, and the Corum novel, The Queen of Swords. The endless and connected worlds of the multiverse are introduced in this novel, as are some of the many identities of the Champion. That Erekosë and all his other incarnations are fated to battle forever is also hinted at.

Moorcock describes this novel as “the shout of a young man who finds the world is a more complicated place than he imagined and feels, therefore, betrayed.” That seems a perfect description of The Eternal Champion. Erekosë, from the moment he arrives in the other universe, is ready to lead humanity into genocidal war against its implacable foe and swears an oath to do so.

Moorcock describes this novel as “the shout of a young man who finds the world is a more complicated place than he imagined and feels, therefore, betrayed.” That seems a perfect description of The Eternal Champion. Erekosë, from the moment he arrives in the other universe, is ready to lead humanity into genocidal war against its implacable foe and swears an oath to do so.

He can remember, if not clearly, that he has fought for such high stakes before, and knows in his heart he will do so again. If humanity is to survive on this world, he must abide by his oath. In the end, he cannot.

As much as he says he is suspect of simple notions of good and evil, Moorcock had little trouble depicting both Eldren and humans in very simple ways. It’s the weakest part of The Eternal Champion, making Erekosë’s actions foreseeable. The Eldren are so noble they have deliberately handicapped themselves in the war against humanity in order to hold true to promises they made themselves ages earlier. Humans have no compunction against deceiving the Eldren and breaching all rules of honor in order to kill them. The Eldren are elegant and immortal, while humans fight each other endlessly and practice slavery. There is absolutely no nuance to this presentation of Good Guys and Bad Guys.

This is not a great book by any measure. Erekosë doesn’t have much depth and the plot is simple and predictable. It is, however, an important book. As Moorcock notes in the introduction to the White Wolf omnibus Elric: Song of the Black Sword, when he started writing S&S in the late fifties and early sixties, he was the only one doing so. Howard existed in limited releases from small presses and Leiber had stopped writing Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories.

Moorcock’s heroes — Erekosë being no exception — are the antithesis of the brawny barbarian warrior. They are sensitive, possessing a deep humanity and empathy. While they will wade through gore if they must, they do so reluctantly and never without a soul-rending awareness of the cost. Moorcock is wary of heroes and the propaganda purposes for which they can be exploited. His explorations of that theme, starting in The Eternal Champion and continuing through many of the stories, is an important element in the evolution of heroic fiction.

If you’re looking to start Moorcock’s Eternal Champion series, I wouldn’t start with The Eternal Champion. I’d go with the Elric or Corum books. There’s more to them and their heroes. The inventiveness hinted at in The Eternal Champion is cranked up by a factor of twenty or so in those series. But if you like them, I’d say you need to come to this one eventually, if only to see how it all started.

I can still remember the first three works I read by Moorcock, all coincidentally enough at around the same time, and all more or less by accident. They give some idea of his range. They were: ‘The Oak and the Ram’, ‘The Condition of Muzak’ and ‘Pale Roses’ – the latter a short story belonging to the ‘Dancers at the End of Time’ sequence.

Corum has always been my favourite eternal champion and I’ve often wondered: is this because he was the first incarnation of the character I happened to read? Or is it the Irish dimension? So it’s nice to know somebody else reckons the series works on its own merits!

Moorcock says he consciously tried to create a character as different from Conan as possible in Elric (who resembles Corum in several important respects) but if Elric et al subvert the notion of the brawny warrior, they also – ironically – conform to a very English notion of the heroic ideal, being mostly of noble birth.

Re ‘The Eternal Champion’. Coincidentally enough, I began reading this again a few weeks ago, after a lapse of twenty years. I’ve always liked the opening scene – which is reminiscent of ‘Prince Caspian’, being told from the perspective of the person summoned as opposed to the person who is conjuring them up – but I couldn’t finish it, partially because it now seems rather dated, partially because I already knew how it ended. I still reckon it’s a respectable effort, though.

Finally a totally random thought – I wonder how much the popular figures of Sixties London influenced the creation of characters like Corum and Elric? I’m thinking specifically of David Bowie.

If I had to pick just one I’d probably say Corum is my favorite as well. One possible reason: He was the last-written of the Big Three (Elric, Hawkmoon, Corum), so maybe Moorcock had just gotten better as a writer by the early 1970s.

Of course, the two Corum trilogies are about as different from each other as it’s possible to be in tone & setting.

I didn’t realize that The Eternal Champion had been expanded until I read the original novella in one of the recent Del Rey Elric collections. It’s possible that it worked better as a shorter piece (I haven’t revisited the full novel in a while) — when I was reading the novella I couldn’t actually identify any points where I missed a bit that had been added to the expanded version.

I think Erekosë came off better in The Silver Warriors — if nothing else, that had one of the all-time great Frazetta covers …

I couldn’t agree more – the two series are totally different. The melancholy, elegaic quality of the sequel serving as a nice counterpoint to the vivid, hallucinatory original

It’s tempting to see this as an indicator of when they were written – the first series reflecting the technicolour Sixties and the second series the drabber Seventies, but as both series were written in the early Seventies, I guess I’m going to have to (regretfully) abandon this particular hypothesis!

I know I like the second Corum trilogy for its dark, wintry setting and the Fhoi Myore. There’s more emotional resonance in those three slim volumes than the rest of the Eternal Champion saga.

The first trilogy is indeed a wild ride through psychedelic landscapes and grotesqueries from the great beyond. Good, exciting stuff.

@ A Fallon – I never thought about that, but sure, all his heroes are noble, highborn men. Funny to get that from a anarchist republican. I don’t know about Bowie, but there sure is a lot of the dreamy-eyed rockstar to Elric and Corum.

@ Joe H – As good as the Del Rey editions look, with the White Wolf set on my shelf I could never justify buying them. I’m hoping to get to The Silver Warriors some time this summer. I definitely remember it as a better book than The Eternal Champion.

I haven to say I like the elric saga the most: it retained the wild eyed, breathless excitement of most of moorcocks stuff, but not without sacrificing its melancholic atmosphere and an intresting, emotional, if somewhat angsty, hero.

The first corum trilogy whilst it was grand in scale, imaginative exciting and all that, it got a little too intangible and a little too metaphysical for me towards the end (although I respect the imaginstion moorcock pumped into those sequences) But the first book was excellent; beautiful and atmospheric.

Still though, the elric saga had it all, and I found myself enjoying it more than moorcocks corum stuff. But then Im yet to read the second trilogy.

@ C Gormley – Totally get your preference for Elric. The series (the 6 books from DAW) is a great for all the reasons you write.

I find the original three Corum books just a little tighter. Unlike the Elric books, it was written as coherent series. The second trilogy, which I heartily recommend, is a much gloomier affair. Thinking back, it might be the first Celtic fantasy I ever read.

That’s one of the things I love about Corum, and about Elric as well — stories that stretch across multiple planes of reality, hopping and skipping from world to world, often leaving destruction in their wake. That’s what I miss in most modern fantasy …

Joe – Don’t get me started on what I miss in a lot of modern fantasy! 😉

In that respect, I think those books do very much reflect the time in which they were written. There may have been a lot of new-age nonsense around in the Sixties and Seventies, but it was a critical (and I would say, positive) influence on fantasy and SF. One example would be mind over matter – the notion that you could levitate or shift between different realities through will-power and concentration alone*.

The reason these ideas play such a compelling part in a lot of Sixties and Seventies speculative fiction is because the writers – on some level – believed in them. We live in cynical times!

* augumented with drugs, if need be.

[…] The Shout of a Young Man Who Finds the World a Complicated Place: The Eternal Champion by Michael Mo… […]

[…] thirty-two novels and over forty short stories. While most of the books were older ones (e.g. The Eternal Champion (1962) and Year of the Unicorn (1965), I did manage to sneak a few newer ones into the mix, as […]

[…] by The Chronicles of Corum, partly triggered by Fletcher Vredenburgh’s comments in his review of the entire series, “The Shout of a Young Man Who Finds the World a Complicated Place: The […]