Jews With Swords: Gentlemen of the Road by Michael Chabon

In 2002, Michael Chabon edited a collection of retro-pulp stories titled McSweeney’s Mammoth Treasury of Thrilling Tales, filled with stories by both literary writers and genre writers. I found it underwhelming. What grabbed me, though, was Chabon’s cri de couer for a return to plot in fiction. And in so doing he wanted writers to be able to use whatever genres they wanted to tell whatever stories they wanted, without fear of being dismissed as no longer writing “literature.”

In 2002, Michael Chabon edited a collection of retro-pulp stories titled McSweeney’s Mammoth Treasury of Thrilling Tales, filled with stories by both literary writers and genre writers. I found it underwhelming. What grabbed me, though, was Chabon’s cri de couer for a return to plot in fiction. And in so doing he wanted writers to be able to use whatever genres they wanted to tell whatever stories they wanted, without fear of being dismissed as no longer writing “literature.”

While he had by then written the superhero-themed novel Kavalier and Klay and the baseball and Norse Mythos mashup Summerland, he was known primarily as an author of literary fiction. From that point on, he threw himself deep into the waters of plot and genre. Since then, he’s written a Sherlock Holmes novella, The Final Solution, the Nebula- and Hugo-winning alternate history novel, The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, and the screenplay for John Carter.

In 2007, as part of his exploration of plot and genre, he wrote Gentlemen of the Road, an unabashed, fun-for-the-sake-of-fun swashbuckler. Hewing to its old roots, it was initially serialized in the New York Times Magazine. His working title and, as he writes, “in my heart the true” one, was Jews With Swords.

While he hoped to invoke memories of Jewish troopers at Antietam or Inkerman, or warriors like Bar Kochba and Judah Maccabee, most people found it too incongruous. But that incongruity, between Jews with swords and the modern steroptype of Jews as decidedly un-adventurous, was something Chabon wanted to explore. He notes that from their very begininning, when Abraham was told by God “lech lecha: Thou shalt leave home,” Jews have been wanderers and “by definition, find adventure.” In his own words, he “attempted to…find some shadowy kingdom where a self-respecting Jewish adventurer would not be caught dead without his sword or his battle-ax.”

Although dedicated to Michael Moorcock, Chabon’s spiritual forebears here are Harold Lamb and Robert E. Howard. This is historical adventure that wouldn’t have felt totally out of place on the pages of Adventure or Oriental Stories magazines. Perhaps the interplay between the two companions is a little more self-conscious than might have been written eighty years ago, but the blood of Gentlemen of the Road is thick and pulpy.

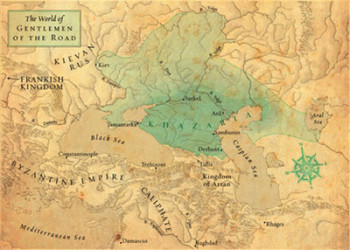

The novel sends a pair of Jewish adventurers into the wild chaotic lands of the Khazars, a kingdom of Jewish steppes people, in the 10th Century AD. Amram is a giant Abyssinan who has served in the armies of Byzantium and carries a great-ax called “Mother Defiler”. Zelikman is a physician and scarecrow-thin Frank from Regensburg. Together, they have drifted into the southern Caucasus, where they’re staging fake duels to the death to con onlookers out of their money.

Following one such scam they’re asked by a mahout to help him get Filaq, the son of the bek — the recently overthrown and murdered ruler of the Khazars — to safety. When the mahout is killed by agents of the usurper, Amram and Zelikman honor their contract and try to take the boy to his relatives. Even when the boy flees, hoping to raise an army of rebellion and avenge his father’s murder, they feel bound to their dead employer’s contract and take off after him.

Following one such scam they’re asked by a mahout to help him get Filaq, the son of the bek — the recently overthrown and murdered ruler of the Khazars — to safety. When the mahout is killed by agents of the usurper, Amram and Zelikman honor their contract and try to take the boy to his relatives. Even when the boy flees, hoping to raise an army of rebellion and avenge his father’s murder, they feel bound to their dead employer’s contract and take off after him.

Filaq’s flight leads Amram and Zelikman further into Khazaria and into the middle of Viking raids and nascent civil war. The new bek is allowing the Kievan Rus to pillage the towns of his Muslim subjects in revenge for atrocities against the Jews of Baghdad. Their pursuit of Filaq brings the con men north along the shore of the Caspian Sea and eventually, at the head of a ragtag army, to the walls of the capital city, Atil, at the mouth of the Volga River.

Chabon’s prose is fun. As bloody and harrowing as some events in the novel are, he never forgets that he set out to write a tale of adventure and derring-do. The action is bold and described wonderfully:

Amram mounted the horse that was nearest him, its girth feverish between his knees. For a moment the shadows and the smell of dust overwhelmed him, and his horse would not move, but he spoke a few words to it in Ge’ez, the mother language of humanity according to his people, the sound of which always had a pacifying effect on horses. As he spoke to the horses around him, they began to follow his mount, Amram squeezing his knees together and telling the horse how beautiful it was and how much he loved it, and they gathered speed and the rest of the herd came after. He could hear the chuff of their breath and now cries from the tents, a shout of the picket on the other side of the camp. The stampeding horses opened up and stretched toward the tents and the guttering fires of the Arsiyah. The moment arrived at which, by his own longstanding custom and the needs of the situation, he should peel off and let the horses carry on through the camp to dispose as they saw fit of the tent strings and the soldiers and rejoin Zelikman on higher ground.

Every characters in this book is given attention and zest. During the hunt for Filaq, Amram and Zelikman rescue a would-be kidnapper named Hannukah, left for dead by his fellow criminals, and who soon becomes their sidekick. In Atil, they receive aid from a long-memoried elephant and find refuge in a brothel run by a madam named Flower of Life. The usurper, Buljan, wears a distinctive hat to address a debilitating infirmity:

Every characters in this book is given attention and zest. During the hunt for Filaq, Amram and Zelikman rescue a would-be kidnapper named Hannukah, left for dead by his fellow criminals, and who soon becomes their sidekick. In Atil, they receive aid from a long-memoried elephant and find refuge in a brothel run by a madam named Flower of Life. The usurper, Buljan, wears a distinctive hat to address a debilitating infirmity:

The hat was a fine piece of workmanship, also from Khitai, yak felt covered in panels of ultramarine silk embroidered in black and silver, but, crippled by headaches that made him sensitive to light, Buljan prized it chiefly for its wide brim.

None of this would have mattered if the shatranj-playing (an old form of chess) Amram and the moody Zelikman weren’t so well-done. They bicker and argue with wit, and Chabon’s portrayal of their friendship, Amram thinks of Zelikman as “the friend of his life”, is completely believable. They know each other well, as is on display when debating the rebellion’s next action:

“You’ve constructed an arguement,” Zelikman observed dryly.

“I was inspired to do so,” Amram said, “when I observed that you were busy constructing a funk.”

The sadness of their pasts — Amram’s young daughter vanished, never to be found, and Zelikman fell out with his father — unites them in a search for something, anything, better down the road, and again, I bought it entirely. When they separate at one point, you know in your bones (ok, if you’ve ever ready any buddy story) they’ll reunite, but it doesn’t feel cheap or sentimental.

I like Chabon’s decision to make these men heroes. Sure, they trick the unsuspecting out of their gold and silver, but they’re never remotely evil or despicable. Annoying as Filaq is, Zelikman feels sorry for him over the murder of his father and the loss of his world. Encountering the wounded Hannukah, his reaction is to use his skills to save him. Amram refuses to abandon Filaq, even when everything seems lost, admitting he wants to see things through to the end and that he likes “the kid.” Despite portraying themselves as carefree “gentlemen of the road” possessed of loose morals and with eyes fixed on the next coin to be snatched, they actually consistently act honorably. In these days of equivocal heroes, Zelikman and Amram are refreshing.

murder of his father and the loss of his world. Encountering the wounded Hannukah, his reaction is to use his skills to save him. Amram refuses to abandon Filaq, even when everything seems lost, admitting he wants to see things through to the end and that he likes “the kid.” Despite portraying themselves as carefree “gentlemen of the road” possessed of loose morals and with eyes fixed on the next coin to be snatched, they actually consistently act honorably. In these days of equivocal heroes, Zelikman and Amram are refreshing.

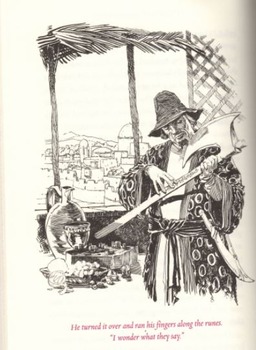

Having been won over by e-books some years ago, I don’t read a lot of new bound and printed ones anymore. Fortunately, I have a real copy of Gentlemen of the Road. Not only does it have a gorgeous cover by Gianni de Conno and a wonderful and useful map by David Lindroth, it’s also filled with loads of dynamite illustrations by Gary Gianni. This is a tremendous reminder of what I miss with e-books.

Gentlemen of the Road is good bit of fun. It’s a frothy escape from the adventureless lives most of us, quite fortunately, lead. Most of the time that’s all I really need in a book.

Rich Horton previously reviewed Gentlemen of the Road here in 2008.

I really enjoyed this one. It’s been somewhat neglected IMO, and I’m glad to see it getting some much deserved love.

I absolutely devoured this book. It has a real Leiberesque feel to it.

@ westkeith – I really like his non-fiction and The Final Problem. After this one I’m really set on reading more of his fiction.

@ K Lizzi – Yes, but without some of the creepiness found in some of Lieber’s stories. Gentlemen is a real blast of a book.

I enjoyed the setting and characters, but was kinda disappointed with the writing, given his reputation. I remember it as straightforward writing, a solid adventure, but nothing new beyond the setting.

@ J Stehman – I found Chabon’s writing fun and never boring. Not brilliant, but much better than a lot of what I read these days. I came at this book having read and enjoyed his book of essays, Maps and Legends (which has THE greatest cover I’ve ever seen) and The Final Problem.

[…] Jews With Swords: Gentlemen of the Road by Michael Chabon […]