A History of Godzilla on Film, Part 5: The Travesty and the Millennium Era (1996–2004)

Hey, kids: guess what comes out in theaters this Friday? Oh, wait … I have something I need to finish up here. (Sorry about the delay. It’s a boring story.)

Hey, kids: guess what comes out in theaters this Friday? Oh, wait … I have something I need to finish up here. (Sorry about the delay. It’s a boring story.)

Other Installments

Part 1: Origins (1954–1962)

Part 2: The Golden Age (1963–1968)

Part 3: Down and Out in Osaka (1969–1983)

Part 4: The Heisei Era (1984–1996)

Addendum: The 2014 Godzilla

Godzilla ‘98: An American Tragedy

Oh, I wish Theodore Dreiser wrote this.

All right, let’s get this mother*&!%ing thing over with as much speed as possible: Godzilla ’98 stinks like rotten Limburger. We can all agree on this. It isn’t the worst film in the Godzilla series, but that’s because it doesn’t belong in the series and has no business associated with anything with the name “Godzilla” on it. It has zero connection to any version of Godzilla, nor does it make any attempt to interpret the monster whose name it crassly exploits — which is probably the most insulting thing about this massive heap of industrial Hollywood sewage.

But even ignoring its crippling Godzilla-lessness, Godzilla ‘98 is a terrible movie on its own terms. Have you seen it recently? Damn, it’s almost unwatchable. Screechingly, aggressively horrible. I prefer the ‘70s Hanna-Barbera cartoon. At least the episodes are short and the theme song is catchy.

There are two bright sides to this fiasco. First, it catalyzed Toho to restart the Godzilla series at home. Second, the monster in Godzilla ’98 would get retroactively, and officially, declared not to be Godzilla. In Godzilla: Final Wars, the monster is identified as “Zilla,” a creature the US military and press mistook for the true Godzilla. The real Big-G faces Zilla in Sydney and, in a moment of extreme fan satisfaction, finishes off the scrawny twerp in five seconds. Eat it, Roland Emmerich!

I would like to point out that Roland Emmerich has at this point made films that directly insult Godzilla and William Shakespeare. I just … I just can’t even…

I would like to point out that Roland Emmerich has at this point made films that directly insult Godzilla and William Shakespeare. I just … I just can’t even…

Out of respect for John O’Neill’s policy about profanity on this website, I shall cease here.

Japan’s Counter Attack: Godzilla 2000: Millennium (1999) and Godzilla vs. Megaguirus (2000)

Back to Japan, where Toho ditched their original plan of allowing Godzilla to remain in the U.S. while Sony/TriStar completed their series. The mediocre box-office showing of Godzilla ’98 made it clear no sequel was coming and Toho recognized that their homegrown celebrity had suffered a public black eye because of the loathed and financially disappointing impostor. They needed the real monster back, fast.

A year later, Godzilla 2000: Millennium arrived on screens in Japan. Although the movie’s crew featured prominent personnel from the Heisei films, with Tadao Okawara returning to the director’s chair and Wataru Mimura of Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II back on script, Millennium breaks away from the previous series with a more down-to-earth, almost subdued, approach. Although the plot revolves around Godzilla battling an extraterrestrial invader, it’s probably the most realistically styled film since 1984’s The Return of Godzilla — although thankfully a far superior entry. The story takes its time building up Godzilla returning to Japan after an unidentified period of time (there are no links to any previous film; Godzilla simply exists and has for many decades) until the confrontation with an alien spacecraft in Tokyo.

Godzilla 2000: Millennium represents a special-effects step forward from the Hesei era, with increased digital compositing that naturalizes the suit-based work. Although Godzilla was shrunk from the 100-meter stature of the last five Heisei movies down to 55 meters (closer to its classic era size), the change allowed for more detailed models. The VFX photography emphasizes Godzilla’s enormity compared to the human cast and military machines, making the monster actually loom larger than ever. The new suit design — which would remain fairly consistent for most of the Millennium era — is one of the best, accentuating Godzilla’s reptilian qualities. The final clash between Godzilla and the alien life form in its adopted shape of a turtle-backed kaiju called Orga contains fantastic choreography and destruction that shifts away from the “monsters shoot rays at each other” style that often bogged down the Heisei films.

However, Godzilla 2000: Millennium is a bit too gradually paced, especially in a middle stretch, where Godzilla vanishes. Some of the heightened enjoyment of the Heisei era also vanished with the more realistic tone. At the time, however, the movie was such a refreshing rebuttal to Godzilla ‘98 that it was hard not to love it. Great or not, this was the real Godzilla.

However, Godzilla 2000: Millennium is a bit too gradually paced, especially in a middle stretch, where Godzilla vanishes. Some of the heightened enjoyment of the Heisei era also vanished with the more realistic tone. At the time, however, the movie was such a refreshing rebuttal to Godzilla ‘98 that it was hard not to love it. Great or not, this was the real Godzilla.

For the first time since The Return of Godzilla, a G-film received a wide theatrical release in the U.S. For the stateside release of Godzilla 2000 (“Milennium” was dropped from the title), TriStar sponsored its own dub using professional Asian-American actors, including François Chau from Lost. It’s one of the best-performed English dubs for any film in the series. Sony also re-did most of the sound design, giving a sonic boost up to the levels expected in North American blockbusters. The U.S. version made some strange choices in the dubbing script — such as including two terrible references to famous George C. Scott lines and mistranslating the movie’s closing line into something hilarious and nonsensical. It also confuses a few plot points about the alien’s purpose. The U.S. version did minor business and the later Millennium films went straight to video from TriStar (although in a timely manner).

Godzilla vs. Megaguirus followed the sober tone of Millennium with outright comic-book antics. Establishing the Millennium series M.O. where each film reinvents the timeline from scratch, Megaguirus opens with a prologue describing an alternate history of Japan where Godzilla attacked the country in 1954, 1966, and 1996, specifically targeting Japan’s energy sources and forcing the government to relocate to Osaka. The prologue concludes with the ‘96 attack, featuring a thrilling scene of the JSDF battling Godzilla on foot with rocket launchers. It makes no logistical sense, but it’s so well executed and more exciting than the majority of Godzilla 2000: Millennium that it hardly matters. The opening also sets up one of the movie’s huge winning qualities: a thunderous score from composer Michiro Oshima, who has created the finest G-film scores outside of Akira Ifukube.

The remainder of Godzilla vs. Megaguirus is outlandish, involving a plot to annihilate Godzilla by hitting the monster with a miniature black hole. (Hey, it’s only a short leap from hand-held rocket-launchers.) The black hole experiment invites a dimensional invasion from insectoid creatures that transform into the monster deerfly Megaguirus (inspired by the Meganurons from the original 1956 Rodan).

Many Godzilla fans don’t enjoy Megaguirus’s willfully outrageous approach. But new director Masaaki Tezuka, who would direct two more (excellent) Millennium films, is more of a classic G-fan than any of the Heisei directors and isn’t afraid to show it. Masaaki engages in every Godzilla style possible, from Engine of Destruction to Action Hero. Godzilla in this movie is all about cool and the final battle with Megaguirus shows the Big-G strutting and posing like a true marquee star. The film is enormous fun and perhaps the Millennium series’ most underrated entry. I don’t even mind Godzilla’s notorious airborne tackle maneuver, the craziest stunt the monster has pulled since the flying double-leg kick in Godzilla vs. Megalon.

Many Godzilla fans don’t enjoy Megaguirus’s willfully outrageous approach. But new director Masaaki Tezuka, who would direct two more (excellent) Millennium films, is more of a classic G-fan than any of the Heisei directors and isn’t afraid to show it. Masaaki engages in every Godzilla style possible, from Engine of Destruction to Action Hero. Godzilla in this movie is all about cool and the final battle with Megaguirus shows the Big-G strutting and posing like a true marquee star. The film is enormous fun and perhaps the Millennium series’ most underrated entry. I don’t even mind Godzilla’s notorious airborne tackle maneuver, the craziest stunt the monster has pulled since the flying double-leg kick in Godzilla vs. Megalon.

An Auteur Enters: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001)

During the second half of the Heisei Era, Toho faced competition from Daiei’s revived Gamera trilogy. These films revamped the campy kid-oriented movies of the 1960-70s into intelligent adult-themed thrill rides, earning enormous respect if not the same financial success as the Godzilla movies. Toho’s brass wanted some of the Gamera goodies, and since the previous two Godzilla movies hardly caused much of a flare-up at the box office, the studio needed to catalyze the series to keep the engines revving. Toho convinced the Gamera trilogy’s auteur, director Shusuke Kaneko, to helm a one-off Godzilla film to indulge in his own view of the King of the Monsters.

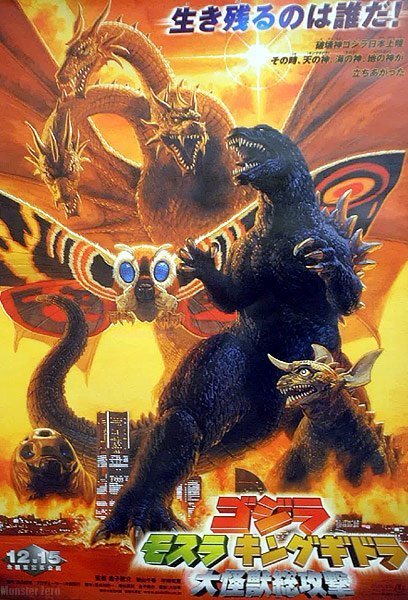

The resulting film with the unwieldy title of Godzilla, Mothra, King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (usually shortened to GMK) both fascinates and disappoints. Kaneko set out to re-interpret Godzilla and succeeded, yet he failed to deliver a movie with the same entertainment level as his Gamera films.

Part of the problem lies in the stunted versions of Godzilla’s adversaries: King Ghidorah is shrunk down and underpowered, in order to make Godzilla the most imposing monster, and Mothra feels lessened as well, although the effects for it are top-notch. A third monster, who failed to make it into the title, appears: Baragon, the tunneling reptile from 1965’s Frankenstein vs. Baragon (first released in the U.S. as Frankenstein Conquers the World). Kaneko was clearly more interested in the lesser-known Baragon than either King Ghidorah or Mothra (he originally wanted Varan and Anguirus instead as Godzilla’s other two opponents), and so the best fight has Godzilla and Baragon ripping it up mid-movie.

Kaneko’s most controversial alteration to G-mythology was to push away from science fiction and toward fantasy that emphasizes the monsters as mystical protector beasts and Godzilla framed as a force of anti-Japanese rage. This is the only Godzilla movie where the title monster can be described as “evil” and not destructive because of an instinct for self-preservation or as a force of nature. Godzilla contains the spirits of the dead soldiers of World War II who feel fury toward their home country for neglecting their memories.

Kaneko’s most controversial alteration to G-mythology was to push away from science fiction and toward fantasy that emphasizes the monsters as mystical protector beasts and Godzilla framed as a force of anti-Japanese rage. This is the only Godzilla movie where the title monster can be described as “evil” and not destructive because of an instinct for self-preservation or as a force of nature. Godzilla contains the spirits of the dead soldiers of World War II who feel fury toward their home country for neglecting their memories.

Since GMK was meant as a one-shot, the changes aren’t crippling problems. This still feels like a Godzilla film, even with King Ghidorah playing the hero against Godzilla, and Kaneko goes out of his way to show the star monster as pure power through impressive sequences with rare displays of civilian casualties. (There’s a tremendous sequence involving a woman in a hospital that ranks among the finest Godzilla film moments ever.) But as the GMK moves toward its climax, it also falls apart and Kaneko simply cannot make the sequence of climatic fights feel climatic enough. The disappointments mount, ending in a prolonged underwater finale that will make most viewers restlessly check the running time. It’s a shame that such intriguing ideas and great effects work ended up as middling entertainment. But the film was a financial success, ensuring the Millennium era continued.

The Mechagodzilla Duology (2002/2003)

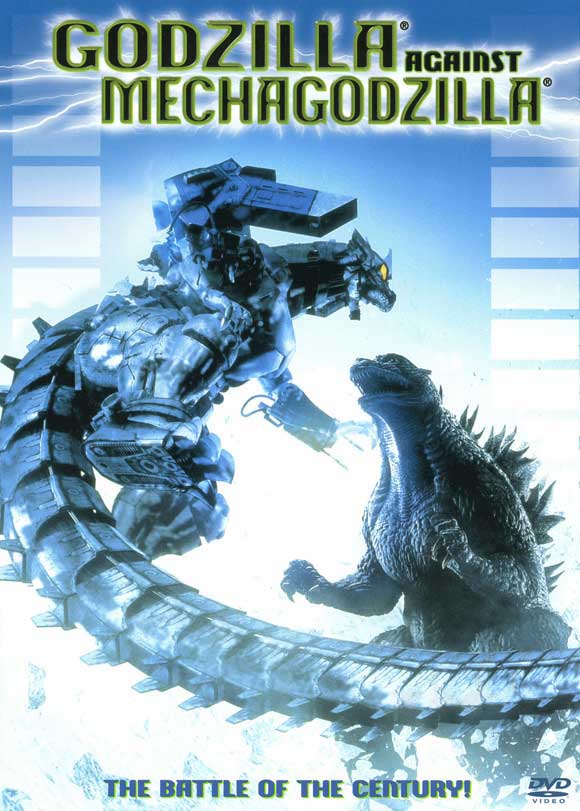

With the Kaneko experiment over, Masaaki Tezuka brought back the Millennium style with the only movies of this series that connect to each other: Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla (2002) and Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. (2003). The two form a tight unit about Japan striking at Godzilla with another incarnation of RoboZilla, given the proper name of “Kiryu” (although the English subtitles insist on translating the name as “Mechagodzilla” even when you can hear the actors say otherwise). Kiryu makes the most story sense of any of the Mechagodzillas, since the robot structure is fused onto the skeleton of the first Godzilla that died in Tokyo Bay in 1954. In concept and design, Kiryu is a massive success and the top adversary of the Millennium years.

Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla is the finest Millennium movie, striking the right balance of comic book stylings, solid characters, well-paced action, and effective world building, plus the best non-Ifukube score in all of the G-movies, courtesy again of Michiru Oshima. (Why a major US studio didn’t hire her to score blockbusters right away can only mean they haven’t seen any of the films she’s done.) The movie feels like a live-action anime, and if that phrase excites you, then Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla is your ideal entertainment.

Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla is the finest Millennium movie, striking the right balance of comic book stylings, solid characters, well-paced action, and effective world building, plus the best non-Ifukube score in all of the G-movies, courtesy again of Michiru Oshima. (Why a major US studio didn’t hire her to score blockbusters right away can only mean they haven’t seen any of the films she’s done.) The movie feels like a live-action anime, and if that phrase excites you, then Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla is your ideal entertainment.

The only aspect of Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla that restrains it from maximum greatness is that Godzilla acts mysteriously sessile at many points, as if the suit were standing empty without a stunt actor inside. It’s bizarre staging and doesn’t resemble Tezuka’s work in his other Millennium movies. Kiryu carries the monster action, leaving Godzilla a touch underwhelming.

The new Mechagodzilla was popular enough for Toho to immediately make a sequel, with Godzilla going into a second round with the giant robot. To boost interest, Toho added Mothra into the mix. Not only does Mothra have a major role, but Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. is a direct sequel to 1961’s Mothra, and has that film’s star, Hiroshi Koizumi, return as the same character, Dr. Chujo. It feels as if director Tezuka wanted to do his own version of Mothra vs. Godzilla, since the Mothra plot has many of the same beats, with double larva battling Godzilla at the end. Although Mothra seems like an odd kaiju to insert into the military tech milieu, it works as a bridge between the theme of “Nature vs. Machine” in the Godzilla vs. Kiryu conflict.

The plot surrounding Kiryu is much less interesting than in Godzilla against Mechagodzilla, with a feeling of repetitiveness to the characters and the sense that the first half hour is rapidly stitched together and then not paid off. There isn’t much new to add to Kiryu; the machine once again provides fantastic battle spectacle (backflip!) but it no longer has as watchable a story surrounding it. The human interaction in general is much less successful this go-round.

The most intriguing and radical decision made for Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. was to have only a single monster fight. Instead of providing a mid-movie fight as a tentpole — the standard structure for the kaiju genre — Tokyo S.O.S. has a single battle that consumes the last forty minutes. It does go on too long and overwhelms all the human aspects, but it contains enough highlights to make the movie another enjoyable Millennium entry. (The problem with the immobile Godzilla suit from the previous movie was also solved.)

The most intriguing and radical decision made for Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. was to have only a single monster fight. Instead of providing a mid-movie fight as a tentpole — the standard structure for the kaiju genre — Tokyo S.O.S. has a single battle that consumes the last forty minutes. It does go on too long and overwhelms all the human aspects, but it contains enough highlights to make the movie another enjoyable Millennium entry. (The problem with the immobile Godzilla suit from the previous movie was also solved.)

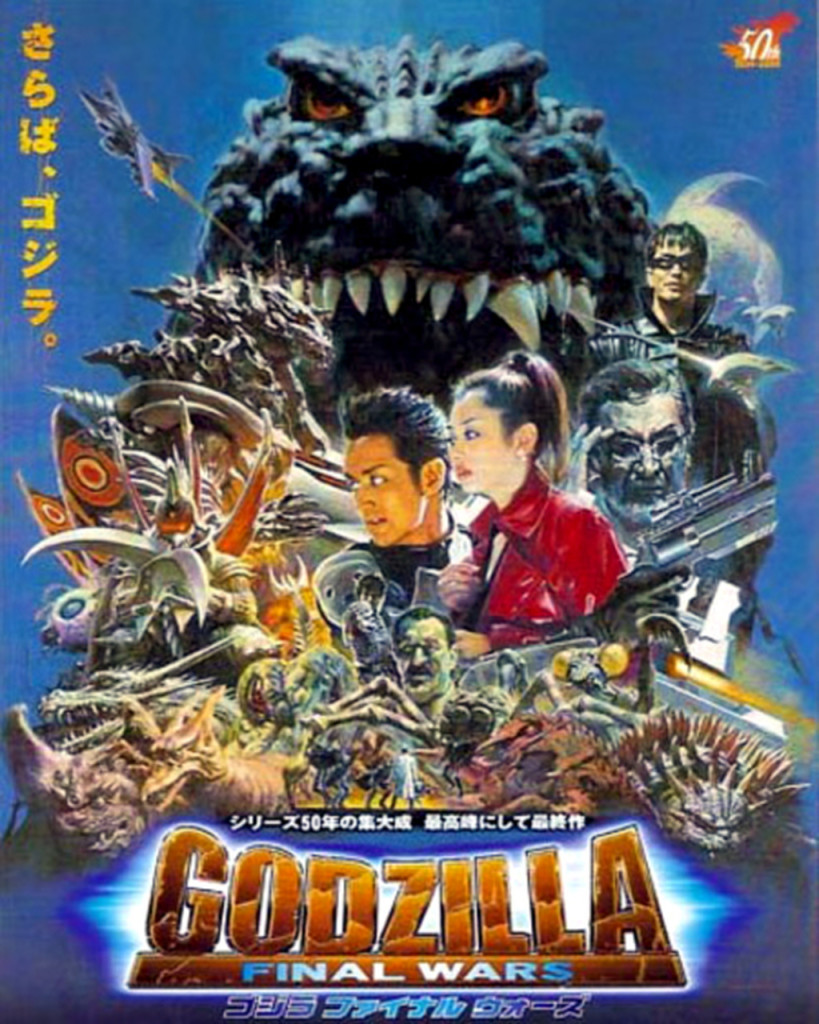

What the…? Godzilla: Final Wars (2004) and Yet Another Ending

GMK was designed as a “director’s film” to allow Shusuke Kaneko to play with his own vision of Godzilla. But the closing Godzilla film of the Millennium Era — and the last Godzilla film until the 2014 U.S. version — is at a level of directorial extreme that makes GMK seem like a studio “yes man” helmed it. Toho turned over the reins to ultra-geek director Ryuhei Kitamura, who then proceeded to cram everything from every previous Toho science-fiction movie, plus massive amounts of The Matrix, the X-Men films, and martial arts flicks—into a phantasmagoria of monster insanity. Godzilla: Final Wars is the strangest G-film of all and it divides viewers sharply. It’s either a blast of fan-pleasing lunacy or an unbalanced mess that hasn’t the slightest interest in the classic monster Ishiro Honda created in 1954. Plenty of fans think it’s both.

Director Kitamura developed a reputation from his zombie action film Versus (2000), which turned him into an overnight cult sensation. Kitamura’s adoration of classic Japanese science-fiction films, particularly kaiju movies, landed him the job on what Toho envisioned as the last Godzilla film for the foreseeable future. Essentially, Toho wanted another Destroy All Monsters, a movie that was also intended as a close to the G-series, and Kitamura had the nerdish enthusiasm to feel right for a project that threw together a record fifteen monsters: Godzilla, Mothra, Rodan, Minira, Gigan, King Ghidorah (called “Keizer Ghidorah”), Anguirus, King Seesar, Kamacuras, Manda, Kumonga, Zilla, Ebirah, Hedorah, and new kaiju Monster X (which transforms into King Ghidorah). A few of the kaijus have little to do — Hedorah flies out of the water and splats into a building, the end—but most of them at least receive one great soloist moment.

I can’t decide from day to day how I feel about Godzilla: Final Wars. I appreciate how unrelentingly geeky it is and how it celebrates the history of Toho, from Godzilla to more obscure pictures like Gorath and Atragon. But the movie is also bloated with too much non-monster action centered on mutants, aliens, motorcycle chases, and wire-work martial arts fights. Ryuhei Kitamura wanted the audience engaged in more than monster battles — an admirable approach — but viewers don’t come to a Godzilla film to watch other kinds of action sequences away from giant monsters. With so many beasts packed into 125 minutes, the other set pieces drain away from the headliners’ screen time. Kitamura has called the movie a “Best of” album, except this album has numerous tracks of filler from some decent bands that simply don’t belong with the A-listers. (Speaking of music, Keith Emerson’s score is a huge miscalculation, especially in the wake of Michiru Oshima’s scores.)

I can’t decide from day to day how I feel about Godzilla: Final Wars. I appreciate how unrelentingly geeky it is and how it celebrates the history of Toho, from Godzilla to more obscure pictures like Gorath and Atragon. But the movie is also bloated with too much non-monster action centered on mutants, aliens, motorcycle chases, and wire-work martial arts fights. Ryuhei Kitamura wanted the audience engaged in more than monster battles — an admirable approach — but viewers don’t come to a Godzilla film to watch other kinds of action sequences away from giant monsters. With so many beasts packed into 125 minutes, the other set pieces drain away from the headliners’ screen time. Kitamura has called the movie a “Best of” album, except this album has numerous tracks of filler from some decent bands that simply don’t belong with the A-listers. (Speaking of music, Keith Emerson’s score is a huge miscalculation, especially in the wake of Michiru Oshima’s scores.)

However, all the monster scenes are terrific with the best special effects of the Millennium movies. Even when the monster fights launch into overtly silly territory, like Godzilla defeating the team of Rodan, King Seesar, and Anguirus in a game of Shaolin soccer using Anguirus as the ball, they are pure kaiju fun. Gigan is the movie’s big surprise: a fan-favorite monster who has the misfortune of appearing in two of the worst Showa movies, Gigan now receives featured villain status and Kitamura lavishes immense love on the cyborg. Ebirah also receives a stunning sequence, where a team of mutants takes on the giant lobster and manage to defeat it on their own. Who ever thought Ebirah would be a highlight of a Godzilla film? Rodan also makes a fun appearance in New York and it was actually filmed in New York!

The best nod Kitamura made to the classic Showa era Godzilla films was giving large roles to three legendary ‘60s Toho SF actors: Kumi Mizuno, Kenji Sahara, and Akira Takarada. Takarada is a blast and clearly having the time of his life as the gun-wielding UN Secretary-General. Another astute casting choice is MMA fighter Don Frye as the captain of the film’s version of the super-sub from Atragon. Although Frye is not an actor by training, he brings a granite-jawed American tough guy persona that recalls Nick Adams in Invasion of Astro-Monster and jolts the movie the same way Adams did. Every moment Frye takes center stage, the human action leaps up a notch.

Godzilla: Final Wars flopped spectacularly. Apparently, Kitamura’s mad monster party burrowed too deep into G-series fandom to translate to mainstream audiences. Toho’s hiatus plans ended up coming true this time and the Godzilla series went into hibernation for the longest span yet. Toho announced they would not produce another G-film for ten years.

Although ten years did pass before the next film, it wasn’t Toho that made it …

We’ll see how that turned out this weekend.

NEXT: The return to the US: Warner Brothers’ and Legendary’s Godzilla.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

I couldn’t agree more about 98. I’d like to slap those involved with that train wreck. I’m looking forward to the new Zilla movie. After watching Pacific Rim I was hoping that the big monster movies might make a comeback.

Who is you pick for favorite Godzilla adversary (besides my grand pappy King Kong)? I personally find myself in a toss up between Mothra and the Flying Turtle Gamera.

Farewell to Tyrn was a great read by the way. I see that Turn Over The Moon is out and if available in Kindle you can consider one copy sold.

Hi, Ape, glad you liked “Farewell to Tyrn.” Unfortunately, Turn over the Moon is still sitting on the desks of some publishers, waiting for them to say “Yes.” It’s been a longer wait than I’ve anticipated…

Favorite adversary for me is pretty easy: King Ghidorah. That monster is both stunning visually and also a very Japanese monster in style. I love Mothra as well, but not so much as Godzilla opponent as second hero character. Mothra has such appeal as the “beautiful monster.” I also dig Gigan, and I’m glad it finally got be in something more impressive than the two sad Showa movies it first appeared in.

I just can’t wait ’til Friday to wash that Emmericky aftertaste out of my mouth!

Is the ’98 version the one in which something the size of a skyscraper manages to hide in the New York sewers/subway? And nobody knows where it is? Boy, how I laughed.

Yes, the ’98 movie was where part of the plot was that nobody could find Godzilla within New York City.

I recall that in theater at the time, my issue with this wasn’t about a giant monster disguising itself in New York City. My issue was, “Godzilla needs to hide? What the hell am I watching?”

Favorite monster: Clearly King Ghidora, with bonus points for Mecha-Ghidora. (Back in my misspent youth I bought a plastic model kit of Ghidora stomping all over an airfield despite the fact that I’d never seen him in a movie and wouldn’t for years to come.)

The one bit in the American atrocity that I almost liked was when the reporter on TV said the creature’s name was Godzilla and the female lead in the bar screamed, “That’s Gojira, you idiot!” or words to that effect.

I think I like GMK more than you did, although the use of Ghidorah is undeniably weird. Supposedly Kaneko wanted King Caesar and…Anguirus (?) in the movie but Toho overruled him and required Ghidorah and Mothra to give the movie extra oomph. So we get the Godzilla equivalent of a Batman movie in which the hero is actually the Joker.

I think the Millennium Mechagodzilla movies are okay, but I admit that in my mind Mechagodzilla will always be a force of evil. Kiryu doesn’t get me going.

I enjoy Final Wars. The complaints about the Matrix/X-Men influence strike me as overblown since the Godzilla movies never shied away from ripping off other popular movies (Bond in the 60s, Terminator and Aliens in the Heisei era). I figure at least the humans are doing stuff instead of standing around and debating in labs and conference rooms. It’s definitely an overstuffed, over-caffeinated movie, though.

I always get a kick out of the origin of Zilla’s name – because there is nothing godly about him.

Kaneko’s original plan was to have Godzilla face Anguirus, Varan, and Baragon; he wanted all the monsters to feel less powerful than Godzilla. But Toho wanted the bankable names of Mothra and King Ghidorah, so they only let him keep Baragon.

Yes, that was Kitamura’s joke about the name “Zilla”: “The Americans took ‘God’ out of ‘Godzilla.'”

However, the Japanese name of “Zilla” is “Jira,” shortened from “Gojira.” Since “Gojira” is a portmanteau of “gorira” (gorilla) and “kujira” (whale), isn’t this a case where the Americans took the “Gorilla” out of “Gorilla-Whale”?

Ah, but I kid Zilla. He sucks no matter what!

You are right, Mothra was his buddy and I might add a terrific side kick.

@Joe H—I liked the Gojira line as well.

@Ryan—kid Zilla did suck. I think it made the big G look a little wimpy. It is hard to explain but kid Zilla is kinda is like a diaper changing station in the men’s room. Er–something like that.