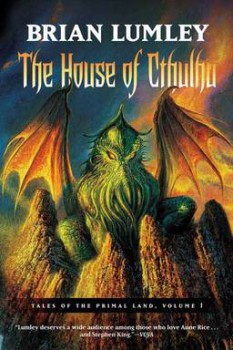

In A Land Before Atlantis and Mu: The House of Cthulhu by Brian Lumley

I imagine that when most people hear the name Brian Lumley, they think of his vast Necroscope series. You know — the books with the malformed skulls on the covers. If your memory is a little longer, you might think of his August Derleth-influenced contributions to the Cthulhu Mythos series, featuring the supernatural sleuth Titus Crow. And in case you didn’t know, he’s also a prolific writer of really great horror short stories. Even if I didn’t love the stories in his collections, Fruiting Bodies and Other Fungi and Beneath the Moors and Darker Places, I’d still love them for their titles.

I imagine that when most people hear the name Brian Lumley, they think of his vast Necroscope series. You know — the books with the malformed skulls on the covers. If your memory is a little longer, you might think of his August Derleth-influenced contributions to the Cthulhu Mythos series, featuring the supernatural sleuth Titus Crow. And in case you didn’t know, he’s also a prolific writer of really great horror short stories. Even if I didn’t love the stories in his collections, Fruiting Bodies and Other Fungi and Beneath the Moors and Darker Places, I’d still love them for their titles.

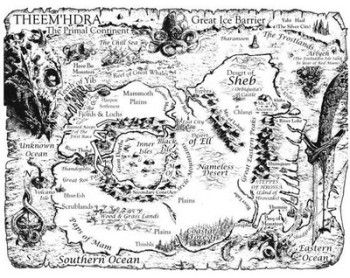

While I did know about all those books and stories, what I didn’t know was that he’d written a whole series of swords & sorcery tales set in Earth’s earliest days on the primeval continent Theem’hdra. I had read a story in Andrew Offutt’s anthology, Swords Against Darkness IV, called “Cryptically Yours,” but hadn’t realized it was part of a much longer series of adventurous stories of wizards and warriors.

Recently, I learned from from Paul McNamee that Subterranean Press was making a lot of Lumley e-books available at $2.99 a volume. I immediately bought three story collections: Haggopian and Other Stories, The Taint and Other Novellas, and No Sharks in the Med. I’ve dipped into all three already and recommend them all.

My buying spree led me to check out Lumley’s website, which led me to something called The House of Cthulhu: Tales of the Primal Land (2010). I learned it was the first of three collections of adventures from the dawn of time. While Tor Books wasn’t selling it as cheaply as the Subterranean collections, I still hit the buy-button. Within minutes, I was traveling back into the deep ages of the world to the Primal Land, encountering giant slug-gods, sorcerers striving for immortality, amoral barbarians, and old Cthulhu himself.

The ten stories in The House of Cthulhu are presented as the writings of the ancient sorcerer Teh Atht. They were discovered by scientist Thelred Gustau as he observed the rising of Surtsey off of Iceland in 1963. Later Gustau, with the help of his friend Brian Lumley, translated and prepared them for publication. During this process, something happened and Gustau vanished. According to his housekeeper, the sound of the professor shouting triumphantly was followed by a deep, booming voice and a loud, splintering sound. She rushed to his study and found the room in a terrible state. Looking out the shattered window, she saw

The ten stories in The House of Cthulhu are presented as the writings of the ancient sorcerer Teh Atht. They were discovered by scientist Thelred Gustau as he observed the rising of Surtsey off of Iceland in 1963. Later Gustau, with the help of his friend Brian Lumley, translated and prepared them for publication. During this process, something happened and Gustau vanished. According to his housekeeper, the sound of the professor shouting triumphantly was followed by a deep, booming voice and a loud, splintering sound. She rushed to his study and found the room in a terrible state. Looking out the shattered window, she saw

A shape like that of a monstrous bird or bat that loomed up massive before rising into darkness to the whirring thrum of great wings, a black silhouette bearing upon its back the lesser shape of… a man!

In a 1984 interview with Robert M. Price, Lumley offered the fantasies of Lord Dunsany and Clark Ashton Smith as his favorites and these stories are reminiscent of theirs, though they aren’t written in as arch or elaborate prose. While he dabbles in faux-archaic prose shaded purple, most of Lumley’s writing aims to be direct and straightforward. The stories themselves are loads of fun and eminently readable. A few even approach greatness.

Theem’hdra is exotic and teeming with bold wizards and rogues of low cunning. In the first story, “How Kank Thad Returned to Bhur-Esh,” the eponymous barbarian falls afoul of the law for numerous vile crimes. Upon conviction, he is sentenced to scale a mile-high haunted cliff that rises above the city of Bhur-Esh. This story, dripping with dark humor, is the most similar to CAS’s tales.

“The Sorcerer’s Book” introduces the ancient mage, and ancestor of Tet Atht, Mylakhrion. Hoping to dedicate himself completely to the search for immortality, the old wizard decides to take on an apprentice. Exior K’mool is in need of a mentor as his previous one “rendered himself as green dust in an ill-conceived thaumaturgical experiment.” It’s in this story that Lumley separates himself from the more cynical CAS. Men in Lumley’s fiction are capable of being honest — sometimes even noble — and they don’t suffer for it. These days, too much of fiction equates honesty with cynicism, so I was taken aback by the end of this one.

“The Sorcerer’s Book” introduces the ancient mage, and ancestor of Tet Atht, Mylakhrion. Hoping to dedicate himself completely to the search for immortality, the old wizard decides to take on an apprentice. Exior K’mool is in need of a mentor as his previous one “rendered himself as green dust in an ill-conceived thaumaturgical experiment.” It’s in this story that Lumley separates himself from the more cynical CAS. Men in Lumley’s fiction are capable of being honest — sometimes even noble — and they don’t suffer for it. These days, too much of fiction equates honesty with cynicism, so I was taken aback by the end of this one.

While The House of Cthulhu technically belongs to the Lovecraftian Mythos, these tales rarely do more than swear by the likes of Yibb-Tstll to establish this, though in the titular story, we do get a full-on encounter with old squid-face himself. “Zar-thule the Conqueror, who is called Reaver of Reavers, Seeker of Treasure and Sacker of Cities” comes to the haunted island of Arlyeh in search of Cthulhu’s House. Despite the dying warning of a tortured priest and another from the priest’s brother, Zar-thule is convinced the tentacled god’s dwelling must be filled with treasure. You can imagine how wrong he is.

“Tharquest and the Lamia Orbiquita” is about a thief’s plan to survive a lamia’s deadly ardor and escape with her treasure. Tharquest’s effort to outwit the lamia is well told, but it is Lumley’s description of the thief-ridden city, Chlangi, that showcases some of his best, straight ahead descriptive writing. The crumbling town’s malodorousness nearly rises up off the page.

But now the city was shunned by all good and honest men… In that time the gold had been stripped from all the rich roofs and the vines of the glass-grapes beyond the north wall had grown wild and barren and gross so as to flatten their rotting trellises. Arches and walls had fallen into disrepair, and the waters of the aqueducts were long grown stagnant and green with slime. Only the rabble horde and their robber-king now occupied the city within its great walls, and without those walls the ravenous beggars prowled and scavenged for whatever meager pickings there might be.

In “To Kill a Wizard,” the elderly Mylakhrion must fend off a barbarian bent on killing him. The trouble is he doesn’t want to kill the warrior, no matter how despicable he is, and his familiar, Gyriss, is less than loyal.

“Cryptically Yours” is composed entirely of letters between Teh Atht and his old schoolmate, Hatr-ad the Adept, sent from places like the “Domed turret of Hreen Castle” on the “Eleventh Day of the Season of Mists, Hour of the First Fluttering of Bats” or the “Sepulcher of Syphtar VI” on the “Thirty-eight Evening, Hour of the Unseen Howler.” This one, as the two correspondents write back and forth trying to determine who is killing their colleagues, is filled with fun bits and an entertainingly gruesome denouement.

In “Mylakhrion the Immortal,” Teh Atht’s experiments into summoning spirits out of the past bring him into direct communication with his long-dead ancestor. The final results of Mylakhrion’s search for immortality are revealed here. Not a bad story, but the least interesting of the book.

“Lords of the Morass” is the most action-packed story in The House of Cthulhu. Two gold prospectors, in search of a great vein of ore, travel into a jungle filled with pygmy cannibals and giant slugs worshipped as gods.

“Lords of the Morass” is the most action-packed story in The House of Cthulhu. Two gold prospectors, in search of a great vein of ore, travel into a jungle filled with pygmy cannibals and giant slugs worshipped as gods.

I love the prospector Dreen’s musings on the arduous lengths he and his partner will go to in order to acquire gold:

Men will kill for it; women sell themselves for it; its lure is irresistible. It brings dreams sweeter than opium and its colour has trapped the warmth and lustre of the very sun. It has a marvellous malleability all its own, and its great weight is that of the pendulum of the world!

What starts as a simple story of adventure in an unexplored land turns into an almost touching story of abiding friendship and sacrifice. It might be my favorite story in the collection.

The final two stories, “The Wine of the Wizard” and “The Sorcerer’s Dream,” involve time and dimension traveling. The first involves the strange link between Thelred Gustau’s nephew Erik and a young man in the late ages of Theem’hdra named Ayrish. Ayrish, an orphan, is the only man in his village willing to stand up to the terrible sorcerer Arborass.

“The Sorcerer’s Dream” brings the tales of Teh Atht, and the very world itself, to a conclusion. Hoping to steal the secret of immortality from dread Cthulhu, Teh Atht foolishly tries to peer into the god’s terrible dreams. Again, I suspect you can make a fair guess as to how the wizard’s plans work out.

The House of Cthulhu is the sort of book that becomes all the more enjoyable because it’s completely unexpected. Until a week ago, I was completely unaware of its existence. For two and a half years, I’ve been on a constant hunt for S&S I haven’t read and this one managed to escape my detection. It’s not great literature or very deep, but it’s a blast of fun.

If you have any taste for the sort of S&S that flourished in the 1970s and ’80s, this is so worth your time. I know I’m going to have to buy the two remaining volumes in the series, Tarra Khash: Hrossak! and Sorcery in Shad, much sooner than later.

I really need to revisit these at some point. You might also want to check out his Hero & Eldin books, beginning with Ship of Dreams — they’re sword & sorcery but set in Lovecraft’s Dreamlands.

And the never-ending wishlist continues to grow…

@ Joe H – I’ve been tempted by them for some time and your recommendation makes it more likely I’ll hit the buy button soon – I actually have a paper copy of the first one (somewhere in a box whose immediate location I’m uncertain of so I’ll probably just buy a new one).

@ Paul – ain’t it the truth.

What Paul said.

[…] In A Land Before Atlantis and Mu: The House of Cthulhu by Brian Lumley […]