Why We Keep Weaving These Webs

My buddy Gabe and I, when we first met almost two decades ago, we knew — man, we knew our stuff was better (or was going to be better) than just about anything out there. It was the haughty arrogance of youth and ego, plus the fact that we just hadn’t read nearly as much of what was out there as we have now.

My buddy Gabe and I, when we first met almost two decades ago, we knew — man, we knew our stuff was better (or was going to be better) than just about anything out there. It was the haughty arrogance of youth and ego, plus the fact that we just hadn’t read nearly as much of what was out there as we have now.

Consider, too, the impressions we’d formed in our teen years of what was most prevalent in the various popular-media streams: the (much smaller) fantasy book aisle was dominated by Terry Brooks and many lesser Tolkien imitators churning out derivative high-fantasy formula. Comics were still stuck in stunted-development adolescence, just on the cusp of the revolution when writers like Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman would kick that medium in its juvenile ass. Films were mostly sci-fi knockoffs of Star Wars or B-grade fantasy with special-effects budgets so meager they wouldn’t fund a single episode of a typical SyFy TV show. And television animated fantasy didn’t aspire much beyond Hanna-Barbera cartoons and He-Man.

In short, based on that narrow and selective assessment, any cocksure young tale-weaver could survey that crop and think, “I can do better than that.” But we weren’t the only Gen Xers who nursed such thoughts. Many others could also do better, and they have.

With our generation, speculative fiction has entered into what seems a golden age, borne out in all those mediums — books, comics, film, television (and add another medium that was just emerging from its nascent stages when we entered the fray: video games). Individuals with tastes and perceptions kindred to our own are drawing on the best of the past like never before, fusing with modern sensibilities what they mine from those rich veins to create some of the finest work the genre has ever seen.

And they’ve infiltrated all levels of the creative business. When I watch old He-Man and She-Ra reruns with my kids, I get the impression that those writers were just lazily phoning it in for a paycheck and couldn’t give a damn about the words they were putting to paper or the stories they were slapping together. Contrast that with the short-lived He-Man relaunch (2002-2004). It wasn’t a stand-out show by any means, but it was heads above virtually anything that cynically aired in the early ‘80s to sell us toys from Mattel and Kenner and Hasbro. Yeah, that particular corner of the market still exists to sell toys — to our kids and grandkids now — but the people who are creating the product were kids like Gabe and me, who thought, “Man, if I could have a job writing that show, I would make it so cool.” And they do have those jobs, and they are.

So where does that leave us, web-weavers in a surfeit of webs?

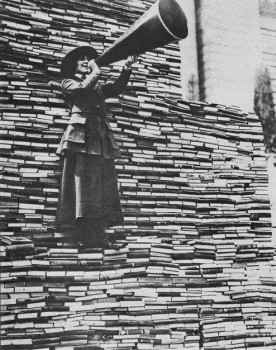

And I do mean a surfeit. I am persuaded that the following is a true statement, at least for myself and for most of you reading this (and thank you for reading it by the way — you do have a lot of options out there): Even if one limits this observation just to the categories of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, there will still be more novels, comics, films, and television episodes produced this year alone that are good — cool, innovative, entertaining, and sometimes downright bad-ass — than you would be able to consume if you spent the next decade at it.

And I do mean a surfeit. I am persuaded that the following is a true statement, at least for myself and for most of you reading this (and thank you for reading it by the way — you do have a lot of options out there): Even if one limits this observation just to the categories of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, there will still be more novels, comics, films, and television episodes produced this year alone that are good — cool, innovative, entertaining, and sometimes downright bad-ass — than you would be able to consume if you spent the next decade at it.

Let me illustrate: a quick check of the Wikipedia entry “Books published per country per year” reveals that in 2011, the U.S. alone produced 292,014 new titles and editions. What percentage of those fall into the speculative fiction categories? I have no idea, but for the sake of argument let’s say 10 percent. And let’s say that 1 percent of those would be books you could have read without feeling like you’d wasted your time. That’s, let’s see… 292 books. One year alone, and two more years have now passed, so from 2011 on that number’s already tripled. Better get crackin’.

Or don’t. Just read the books that seem to come your way, whether their covers beckon to you from the shelf at Barnes & Noble and the webpages of Black Gate or they arrive highly recommended from a trusted friend. Catch what you can; don’t sweat all the great stuff you’ll never get to. (Please, trust me, or it’ll drive you insane.)

But to flip it back to the production side of this puzzle: why would I want to toss another strand out onto that crisscrossing pandemonium of webs — one more filament nearly invisible against hundreds of thousands, some thick as rope or steel chain beside my meager line of lies?

Any trueborn storyteller knows the simple answer to that: because you must. It’s in your DNA, like the spider’s drive to spin webs. Not just to catch food: a spider can be provided with food so that it never again has to trap prey, but it still has to spin or else, I don’t know, all that webbing would clog up its butt or something. (And can you see why I’m a writer, folks? — look at that magnificent analogy. Or don’t. It’s kind of revolting.)

But the logical ancillary question still lingers: who are we writing for? Really, is it for all those people who are never going to get through even a fraction of the great stuff out there? I’m sure they appreciate it, truly (although I can’t help but picture them as the guest at the potluck who is stuffed, and someone else is begging them to try just a bite of the dish she brought). You’re waving your latest book or short story around and they’re throwing up their hands saying, “Really, it’s not necessary. It looks lovely, but I already have a stack on my nightstand that’s threatening to topple over.”

For Gabe and me, it’s a question that’s come up in our conversations more often lately, as we enter middle age and naturally re-assess why we’re still playing at this. Gabe once noted that the imaginary audience he had in mind when he sat down to write was simply Fred (Durbin) and me, friends who comprise our informal writers’ group the Inkjetlings. “I wonder what Fred and Nick will think of this?” When his girlfriend came along, she expanded the audience to a triad. Recently, he told me that he wants to write for his progeny. “Maybe my grandkids will one day wonder what Grandpa Dybing thought, how he saw the world, what stories he dreamed up.”

For Gabe and me, it’s a question that’s come up in our conversations more often lately, as we enter middle age and naturally re-assess why we’re still playing at this. Gabe once noted that the imaginary audience he had in mind when he sat down to write was simply Fred (Durbin) and me, friends who comprise our informal writers’ group the Inkjetlings. “I wonder what Fred and Nick will think of this?” When his girlfriend came along, she expanded the audience to a triad. Recently, he told me that he wants to write for his progeny. “Maybe my grandkids will one day wonder what Grandpa Dybing thought, how he saw the world, what stories he dreamed up.”

That’s not a bad call. Dreams of fame and fortune can be fun (like occasionally daydreaming about what you’d spend the money on if you won the lottery), but humor them too much and you’re probably setting yourself up for some major disappointment.

Look, you can come up with a brilliant new series with a cool setting, great characters, and some innovative concept or original twist — you can have all of that, and you’ve got what many others out there have got too. Maybe for every hundred such worthwhile projects, one will catch on — get picked up, enter the Zeitgeist, “go viral,” or however you want to describe it. If yours is one of the other 99, I think the best one can hope for is that you glean real pleasure from the act of imagining and creating it, and that you find a few like-minded people who will also enjoy it. The best-case scenario is likely that you develop a small “cult” following that will appreciate what you have wrought and loyally follow its arc. If that would make you happy, then by all means proceed. It keeps me going.

Because being the next hot thing? Even if you have all the right elements combined into a winning formula that could be the next hot thing, all this does not guarantee it will be. There is then the additional catalyst of luck, which can look a lot like totally random, capricious happenstance. Your project may be brilliant — it’s still one among hundreds of other projects that are equally brilliant. Predicting which will be invited to the big-time is about as reasonable as predicting where lightning will strike, or which combination of numbers will win this week’s Powerball. It does happen, but it is almost entirely beyond your control.

So that leaves you with what is in your control, with what you can pull off just on your own perseverance and pluck. If you have some competence as a writer, some skill as a world-builder, some talent as a storyteller; if you put your heart and mind into creating something exciting and worthwhile; and if you stick to it, then it is entirely probable that you will find and build up a small audience that will welcome and appreciate what you have done. Especially if you reach them young — if your story happens to be one of their early gateways into the realms of the fantastic — your work can take on special importance to a few people.

If you knew in advance that this is all it would ever amount to, would you still put all the time and effort into it? I think I would. That would be enough. I’d love the prestigious awards and packed rooms at conventions, but I’ll still take it if it’s just one or two people coming up to me and saying, “Hey, I really enjoyed that tale you spun.”

_________________________________________________________________________________________

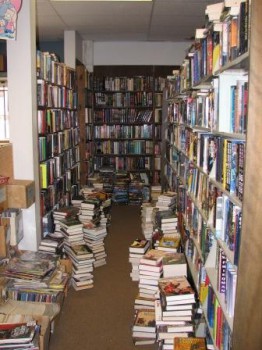

The photo of the overflowing book aisle at the top of the post is Uncle Hugo’s Science Fiction Bookstore in Minneapolis. I was up there this past winter, but neglected to get any good pics. This one was taken by Amy C. Rea; her full review of the bookstore can be found here.

I can remember reading how Bob Howard felt as if Conan was real, that some nights Conan would be leaning over his shoulder, watching, almost threatening Howard to get the story down. I used to think that was crazy. Not so nowadays.

The more fiction I write, over a million words now (I’m not saying it’s all good, but hey), the less I feel like I’m creating than I do like I’m syphoning characters and events from another world. And perhaps I am, at least if the many worlds theory of quantum mechanics should be true.

Which brings up my point. I don’t write just for myself, or even for my readers (both of them). I also write for my characters, because they have stories needing told.

But yeah, it’s nice to hear, “Hey, you don’t suck,” from time to time. 🙂

At least book writing has a self-publishing option. Assessing your chances of becoming a successful screen writer (even if you get good at it) is beyond depressing. The amount of screenplays that never get read by anyone other than a gate keeper: if even then.

@Ty: That is one of the most amazing experiences for a writer, when you get hit with something where you feel less like a fabricator and more like a chronicler, just reporting the story as the Muse delivers it to you. It’s happened to me a couple times — a story comes full-blown, I get it all written down, then look back at it and go, “Where the hell did that come from?” One can get mystical about it, speculate on what T.S. Eliot described as the collective unconscious delivering the work to the receptive outlet. And it could just have a natural psychological explanation. But it is a real phenomenon, either way. Tolkien also described that sense with Middle-Earth that he felt like he was merely recording events rather than making them up.

@Bob: The explosion of self-publishing has really made that option I describe at the end of the post more readily achievable. Even if you can’t get signed on to a traditional publisher (increasingly difficult these days as they merge and drop mid-list authors), you can still get your work out there. With a little gumption, dedication, and time, you can find and reach that audience for your work on your own horsepower. It may not be a big audience, but it may not have been even if you’d been picked up by a major publisher — we’ve been talking a lot about Michael Shea here since he passed away, how his work was so cool and innovative, yet here it is all out of print and difficult to find. But if your work has any merit at all, those who will get something out of it are out there.

About screenwriting — yeah, that’s an aspect of the situation I alluded to: there are far more people who can write a decent screenplay than there is a need for screenplays. That’s just the reality. What’s depressing is when you see the latest Transformers movie and you can immediately think of 20 people you know personally who could have written a better script, and who would have gladly taken the $300,000 for doing it. I know why so much good stuff is getting made these days in television, film, comics, books — what always puzzles me, with the surplus of good writers, is how the bad stuff still manages to get produced and shoved down our throats.

Corollary to that last point about screenwriters — and it has nothing to do with the topic of writing, but I’ve always wanted to get this off my chest: every time I sit down and watch some recent low-budget, independent film where the places on screen that would normally be filled by actors are occupied by people who have obviously never acted and never will again after this thing finished shooting, I think about how it doesn’t have to be that way. There are literally thousands of acting troupes across this country, from community theaters to small professional troupes. I was part of one myself a decade back, and I know many fine stage actors who would get a kick out of taking a week or two to do a B-movie. It’d be fun, and they’d get to list an actual movie on their resume. They’d do it for next to nothing (there’s a reason these people are called “starving artists”) — maybe a couple hundred bucks, pay for lunch, and promise a free copy of the DVD if and when it ever comes out. Instead of no-name non-actors (mostly just acquaintances of the aspiring director), you could have no-name actors who can actually act. Never understood that. For any aspiring low-budget director/producer, I could find a handful of decent actors within a hundred miles of any location in the United States. Just look up the local community and (non-Actors’ Guild) professional theater troupes, make a few calls, and you’d find some eager folks. But what do I know. I just have to sit here and watch these poor fish-out-of-water folks deliver lines like they’re rejects from the Borg, and think about how one of my starving-actor buddies could’ve and would’ve nailed that part. I guess the networks just aren’t there to hook these people up, but in this age of the Internet, they should be.

Nick, beyond my few experiences screenwriting, I know little about the film industry, or at least no more than the average fanboy who watches DVD extras. But about using local actors, I have to wonder if it comes down to two things:

1.) The director is making use of buddies and the like, perhaps people who were promised a small role for some financing or simply because they’re old friends.

2.) Maybe a couple of hundred bucks and paying for lunch is a lot for the producer/director. I don’t know, but it wouldn’t surprise me if some indie filmmakers, especially students, are operating on such a tight budget. I don’t mean this as an excuse, but only as a possible reality. One might argue they shouldn’t make the film without the finances, but you know as well as I do that it’s going to happen, at least from time to time.

Kickstarter and similar sites might be an option, but it seems crowd funding has been getting a bad name of late, though possibly only because of unfortunate cases that draw attention to themselves.

I am more interested in figuring out which authors and stories have enduring value and will appeal to someone who doesn’t care one bit about the sensibilities of 2014. I bet most of the things hipsters and geeks currently flock to for a few months will be completely forgotten in 70 years outside of forgotten corners of the internet, just like the things of the past this generation looks down upon. Who are the authors writing right now that will be cherished and enjoyed like Howard is today?

To finish my thought – don’t be discouraged that your writing isn’t recognized now. What matters more is if it is read 20, 50, 100 years from now and people of different generations find value in it. I don’t find popularity in 2014 America being a great badge of merit.

I like your comment about comics going through a revolution where they went from “stunted-development adolescence” to a targeting an older audience. Some of the comics made that cut and many did not. I like that comics are not for kids but at the same time they’ve sacrificed story sometimes. I think that is why the sword and sorcery comics appealed to me more than the superheroes. Conan, Arak, Kull, etc. had an edge that the superhero comics did not.

@Tyr: I can certainly relate to that curiosity (and curse the fact that I don’t have a TARDIS to find out). I’m hoping I’ll hang on at least another 40 years — not just to see which authors are still being read, but that’s one thing I’ll be taking note of. (And if I have a means of time travel by then, I’ll send a note back to us.)

@Ty Johnston: Those two factors are certainly most often at play. Sometimes, too, it probably just doesn’t occur to a new director that he/she can go over to the theater department of the nearest community college and find better actors than the people he/she is about to line up.

I can imagine the big deal that will be made of the first crowd-funded film that really makes a splash and goes mainstream (the Kickstarter-era cousin of Resovoir Dogs or el mariachi). It’s probably inevitable — maybe the next Tarantino or Rodriguez is out there right now soliciting backers.

@Wild Ape: Yeah, comics of that era (late ’70s – early ’80s) aimed toward a more mature readership definitely skewed to fantasy/sword-and-sorcery.

Incidentally, there’s a designation for the latter part of my youth (1984-1991) that somehow I’d never heard until yesterday: the Copper Age.

Follows consistently with the Golden, Silver, and Bronze Ages of comics, of course, but now I wonder: to continue that classification, what do we call the comics post-’80s? The Nickel-Plated Age? The Stone Age? And if the designation has really shrunk down to 7-year increments, have we passed through 3 more ages of comics since then? What the hell? Too much to think about this late at night; I think I’m going to turn in.

For 1991-oh, I don’t know, 1995 or 1996 (I pretty much gave up on comics sometime around 1994 or 1995) I’d propose the Foil Age. (Available in three different cover variations, of course.)

Joe, for a moment there I thought you were going to suggest The Clone Age.

And I’m not sure Copper Age fits 84-91. Maybe 84-86 or therabouts. It seems to me the late ’80s and early ’90s were a boom time for indie comics and those trying to look like indie comics (Vertigo, early Image sort of, etc.). If there was to be another age in there somewhere, I would think ’87 to about ’95 would have been a better timeframe, and one of my favorite eras. A still sane Frank Miller, a somewhat sane Alan Moore (as much as he ever was), Neil Gaiman, even Barry Windsor Smith was in on the action, and those were works mostly by major publishers. “Stray Bullets,” “Hard Boiled,” “Love & Rockets,” “Cerebus,” “Bone” … man, I could go on.

Ty — It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. You had Sandman and Bone and Watchmen but you also had Robin #1 and X-Force and endless Punisher and Wolverine appearances. I didn’t have exposure to the full range until I started working in comic stores back from 1990-1994 or so; prior to that, I was pretty much limited to what showed up in my hometown book & magazine store (remember those?!?) and all I was buying was Marvel.