Politics and Fantasy Make Strange Bedfellows

In January, both M. Harold Page and I wrote posts about politics in fantasy literature. While we came at the topic from different points, I think we narrowed in on the same conclusion. I quote from Page’s post:

In January, both M. Harold Page and I wrote posts about politics in fantasy literature. While we came at the topic from different points, I think we narrowed in on the same conclusion. I quote from Page’s post:

Of all the genres, Fantasy must be the worst possible channel for the politically minded author. They simply can’t be heard over that clash of steel and the roar of dragons…

Really enjoyed and appreciated his post. And I do take his point – escapism is great fun and entertaining. But ultimately escape and make believe can only go so far, and at other times and places we will have other needs, other reasons to want to read. Something that touches us inside.

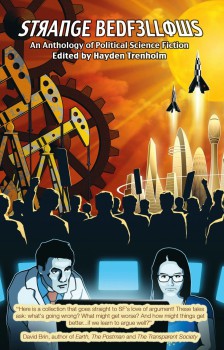

The reason I’m coming back to this topic, perhaps more convinced than I was before of this serious liability in fantasy, is that I’ve just read Strange Bedfellows: An Anthology of Political Science Fiction. I’d mentioned the anthology in my post as something I was looking forward to reading.

Now that I have, maybe I’m having one of those stumbling-upon-a-watch-in-the-heath moments, because, for the life of me, I can’t see how fantasy could have done even a fraction of what this anthology seems to have accomplished effortlessly. A few examples will make this clear.

Eugie Foster is a nebula-award winning author who creates a futuristic rights-deprived Atlanta in “Tried As An Adult” and shows how criminal society have adapted strategies to deal with juvenile penal law.

The main character is a minor, recruited to crime because he can’t really be tried as an adult, but then is detained, just as a new bill, proposing to bring the adult penal code down to 12 years old, is tabled. The story is powerful and horrifying and unfortunately, tells us a whole lot about society, crime, social media, and how we govern ourselves.

Similarly, “Capital Punishment” by f.f. White is an extrapolation of legal science rather than the overtly political. Who has not dreamed that corporations could be properly punished for their crimes? In this story, a corporation can receive a death sentence, but of course, corporate lawyers can find a suitable employee to suffer capital punishment for them. This story is about the implications of a company hiring a depressed, suicidal man to take the company’s punishment in exchange for a $10M payment to his beneficiary. Tightly written, partly wish-fulfillment, partly cautionary tale.

“Afternoon Revolution,” by Clarkesworld writer Erica Satifka, is a grim and relentless look at humanity and inhumanity and how the US is really f&*king it all up with the economic misdistribution of resources driving the decay of America, wrapped in an exciting kidnapping tale.

A similar theme is excavated in “Gloop,” by Argentinian writer Gustavo Bondoni. In this case, it is a straight-up moral struggle between unionist and Ayn Randian philosophies in France and it doesn’t at all end like you’d expect. It’s a powerful statement on the political impotence of the middle class.

And on this political impotence, Analog writer Andrew Barton makes some powerful statements on elections, the morality of terrorism in elections, and the feelings of futility of the average voter in “Three Years of Ashes, Twenty Years of Dust.”

“Occupy Asteroid,” by Trevor Shikaze, tells a story of corporate rights versus societal rights and how they are decided, with colors of environmental symbolism and the implication of the concept of Wikileaks. Despite the jingoistic title, the hero is not overly bright, but he’s a ton of fun, and his transformation, through this tense and action-packed story, is Tiananmen Square in a short story, starring a semi-bumbling underdog.

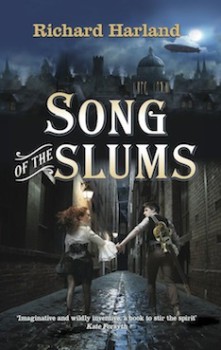

“Homebody,” by Richard Harland, who is most frequently published by Penguin and Pan MacMillan, and is the author of the upcoming Song of the Slums, is the most powerful story in my view. Disturbing and subtle, it holds a mirror to the reader by which to examine his/her cultural tolerance. It’s a story of both wanting a Starbucks in every country you visit, but also an experience of fresh newness, just not too fresh or too new. I experienced this in living 6 years overseas in Latin America, both embracing and rejecting immersion, and knowing the feeling of retreat from strangeness, very much like the nest of the story. Harland set up some specific reader expectations, before turning sideways, leaving me and the hero scratching our heads, not in a bad way, but in a way that shows the cultural gulfs that separate cultures and have everything to do with how we deal with other nations and even with different regions of our own countries.

“Homebody,” by Richard Harland, who is most frequently published by Penguin and Pan MacMillan, and is the author of the upcoming Song of the Slums, is the most powerful story in my view. Disturbing and subtle, it holds a mirror to the reader by which to examine his/her cultural tolerance. It’s a story of both wanting a Starbucks in every country you visit, but also an experience of fresh newness, just not too fresh or too new. I experienced this in living 6 years overseas in Latin America, both embracing and rejecting immersion, and knowing the feeling of retreat from strangeness, very much like the nest of the story. Harland set up some specific reader expectations, before turning sideways, leaving me and the hero scratching our heads, not in a bad way, but in a way that shows the cultural gulfs that separate cultures and have everything to do with how we deal with other nations and even with different regions of our own countries.

So, none of this is escapism. Nor is it the hard scifi of Analog or Stephen Baxter or Alastair Reynolds. This is the region of science fiction where Ursula LeGuin has created her most powerful works. Politics is about how things are decided in our societies and there’s no way to look at power, the lifeblood of the world and the source of most of the conflicts history has ever had, without being taken aback at what humanity is really about. These stories are powerful and they hold a mirror up to the world of right now.

Fantasy is suitable for relevancies about family and society, but I continue to find fantasy particularly unsuited to politics, perhaps in part because everything must be created, so a reader (and a writer) would have a hard time figuring out what the one change is that they should be paying attention to. In scifi, the convention of the best of it is that the laws of science (physics, sociology) and the trajectory of history need to be respected, or where they are not, explained, even if only to say “this isn’t the same.” Science fiction gives writers the flexibility to easily change just one thing.

And here is where my imagination fails me: Can we imagine an exciting fantasy story that says something meaningful and fresh about corporate rights and the concomitant loss of individual freedom? Can we imagine fantasy saying something about juvenile justice or the clash of Ayn Rand and leftist values? And elections being the lifeblood of western politics, can we see a fantasy story changing a reader’s view of politics? I am sad to say I think not, but I wonder if the writers of fantasy today couldn’t be coaxed into giving it a try. There is no shortage of brilliance in today’s writers. But perhaps they all see that fantasy as a form stacks the deck against them doing something really great with a political story.

Fantasy has power, but it uses its power differently, and seems rarely to never to look beyond family or war or the self to look at politics — the way our society is and how power flows. It does not provide cautionary tales or offer alternative ways society could live.

Derek Künsken is a writer of science fiction fantasy and horror. You can find out more about him at www.derekkunsken.com or @derekkunsken.

Science fiction certainly does lend itself to political themes. But I think fantasy can be just as politically powerful, even if you define “political” very narrowly, as the direct examination of a society’s power structures. Animal Farm and The City & the City are two examples that come to mind. Alif the Unseen is another. Or Gregory Maguire’s Wicked (the book, not the musical). In short fiction, Ken Liu is very good at fantasy that provokes political thought. His story Maxwell’s Demon is one example.

Have you read China Mieville?

Hey Kate and SFTheory: I’ve read Perdido street station. Very impressive world building, and I know there were political dimensions, but I feel that those thoughts were swamped by the strangeness of the world and its harsh mores and aesthetics. I will concede that in my research, Mieville was listed as one of the only writers who was even trying to put politics into his fantasy. I haven’t read Maxwell’s Demon, but I’ll look it up! I’m glad that some counter-examples come up, but I worry that they are the exception, rather than a mainstream part of fantasy, whereas going even to foundational works of science fiction like Heinlein and Starship Troopers, the politics is as necessary as the science is to the creation of the art. I’m willing to be wrong, but I wanted to make this point of my post because I think it is a fair one and worth debating

Derek

[…] Review of Strange Bedfellows at Black Gate […]

[…] making of decisions, personal and collective. There’s a review of the book as a whole over on Black Gate. I’ve been reading the rest of the stories (not quite all done yet as my author copy only […]

[…] Politics and Fantasy Make Strange Bedfellows […]

[…] The Auroras also include a related works category which catches collections, anthologies and magazines. Helen Marshall had a new collection called Gifts for the One Who Comes After, as did Matthew Johnson, called Irregular Verbs, and David Nickle, with Knife Fights and Other Struggles. Editor Hayden Trenholm produced a brilliant political sf anthology called Strange Bedfellows (which I discussed in a previous post). […]