Two-Fisted Justice in an Abandoned Cemetery: Will Esiner’s The Spirit

Will Eisner is one of the most revered comic creators of the 20th Century, and for good reason. I’m continually astounded at the skill and command of the medium he exhibited, even at an early age.

Will Eisner is one of the most revered comic creators of the 20th Century, and for good reason. I’m continually astounded at the skill and command of the medium he exhibited, even at an early age.

He was inducted into the Academy of Comic Book Arts Hall of Fame in 1971 and he virtually created the graphic novel with his 1978 masterwork A Contract with God. Comic’s most prestigious awards, the Eisner Awards, were created in his honor in 1988.

So I’m a little disappointed that his most famous creation, the good humored crime-fighter The Spirit, isn’t more well known today.

The Spirit is flat-out one of my favorite early comics. Beginning his career as detective Denny Colt, shot and left for dead in the first three pages of his premiere appearance, the Spirit awakens in the abandoned and overgrown Wildwood Cemetery. From this new base of operations, and with his past virtually obliterated, The Spirit throws himself into life as a crime fighter, disguising his identity with a small domino mask (which he wears even while sleeping), an amazingly resilient business suit, fedora hat, and gloves.

With his sidekick Ebony White, an uneducated but resourceful black orphan (who sleeps in a sock drawer), the Spirit traveled the world, bringing justice to criminals and con men all over the world.

The comic included a large cast of characters, including the beautiful P’Gell, constantly trying to seduce the Spirit into a life of crime at her side; his trusted friend Dolan, Central City’s Police Commissioner; the sinister Mister Carrion, who travels everywhere with his beloved vulture Julia perched on his shoulder; and Hazel P. Macbeth, a witch with potent magic at her disposal.

The Spirit first appeared on June 2, 1940 as the lead feature of a 16-page tabloid color comic section for what would eventually be 20 Sunday newspapers, with a combined circulation of nearly five million. “The Spirit Section” continued for a dozen years, until 1952. Eisner, who edited the entire tabloid, writing and drawing additional strips like Mr. Mystic and Lady Luck, was only 25 when it began.

The Spirit first appeared on June 2, 1940 as the lead feature of a 16-page tabloid color comic section for what would eventually be 20 Sunday newspapers, with a combined circulation of nearly five million. “The Spirit Section” continued for a dozen years, until 1952. Eisner, who edited the entire tabloid, writing and drawing additional strips like Mr. Mystic and Lady Luck, was only 25 when it began.

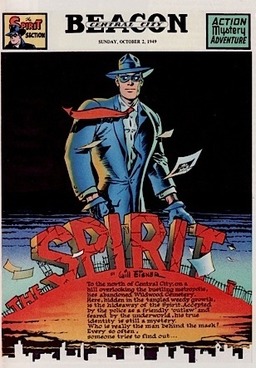

The cover of the Sunday, October 2, 1949 issue of “The Spirit Section,” featuring perhaps his most iconic image,The Spirit standing atop a windswept hill looking down at his city, had this teaser for the story inside, which I think perfectly encapsulates the series.

To the north of Central City, on a hill overlooking the bustling metropolis, lies abandoned Wildwood Cemetery. Here, hidden in the tangled weedy growth, is the hideaway of the Spirit. Accepted by the police as a friendly ‘outlaw’ and feared by the underworld, his true identity is still a mystery. Who is really the man behind the mask? Every so often, someone tries to find out…

Many have drawn the obvious parallel between the Spirit and Batman, and I can see the connection. Both are obsessed with crime fighting, both rely on skilled detection rather than superpowers, and they’re both brilliant detectives and unparalleled brawlers.

But I think the Spirit — whose exploits were usually on a much smaller scale than Batman’s, his adventures more personal, and who’d just as readily get into a snowball fight with Dolan than mix it up with gangsters — had more in common with Carl Bark’s tenacious and adventure-seeking Uncle Scrooge than Batman.

Certainly Esiner hewed closer to the visually creative Barks than, say, Bob Kane’s stiff style in Batman. Every page of The Spirit is stuffed with sight gags, marvelous architecture, and the kind of fluid, seemingly effortless action that irresistibly draws the eye.

I’m disappointed that more modern comic readers haven’t read The Spirit, but it’s not like he’s been ignored. The character has been republished and revived almost continuously since the 40s.

Will Esiner moved on to other endeavors after “The Spirit Section” ended in 1952, returning only to paint covers for the various comic book versions and produce two short additional stories in the 70s. But he wrote so much material in the 40s that it provided a seemingly endless (to me, anyway, a young comic fan in the late 70s) supply of strips for reprint books.

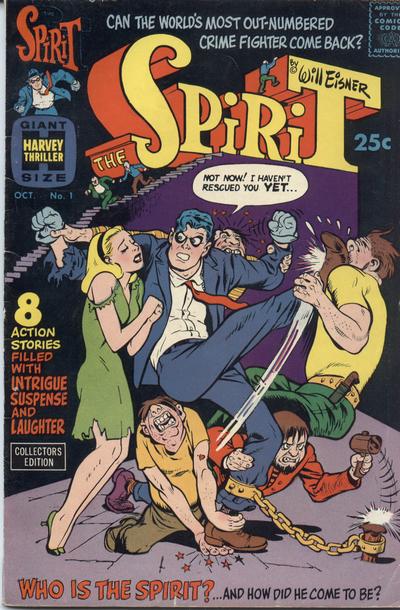

Harvey Comics, publishers of Caspar the Friendly Ghost, Richie Rich and Sad Sack, produced the first reprints in 1966-67, with two giant-size, 25-cent comic books, both under new Eisner covers. The first one remains one of my favorite Spirit covers of all time.

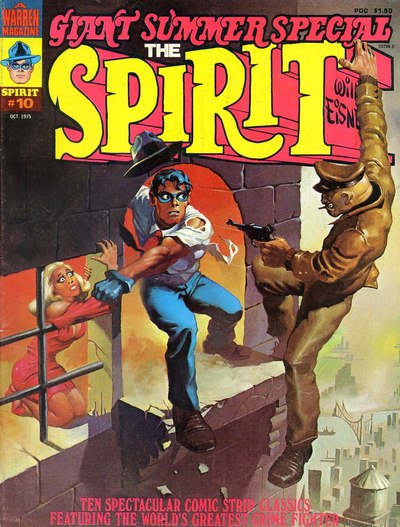

In the early 70s, Warren Publishing, publishers of large-size, black-and-white comics for older readers like Creepy and Vampirella, launched an ambitious magazine of black-and-white Spirit reprints. They took a very different tack than Harvey, with bright, gorgeous covers.

Like this example from issue #10, penciled by Will Esiner and inked and colored by Ken Kelley, featuring the Spirit in Nazi Germany (click for bigger version):

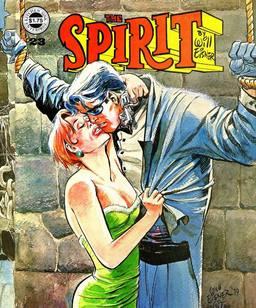

Kitchen Sink took over with issue 17, maintaining the numbering and format. The Spirit reprint magazine, with marvelous new covers by Esiner and the rare new story, lasted over 30 issues. That’s issue 23 of the Kitchen Sink b&w title at the top of this article, with the Spirit tied to a dungeon wall and staunchly resisting the tormented attentions of the adventuress Silk Satin (click for a bigger version).

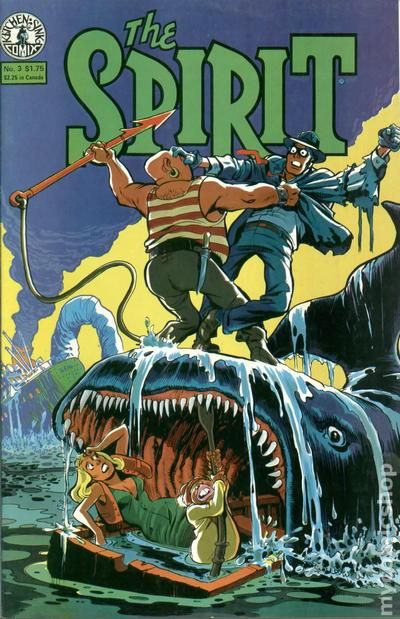

Kitchen Sink made another attempt in the 80s, this time with a color book reprinting all of Esiner’s post-WWII work. Here’s issue #3.

This was the first time I remember encountering The Spirit, buying these treasures at Arthur’s Place on Bank Street in Ottawa in the early 80s as they were released. I remember being enchanted — and constantly amazed that the entire series had originated in the 1940s.

Kitchen Sink began another title, with the goal of reprinting the pre-WWII The Spirit tales; that one lasted only 10 issues. In the 90s, they invited some of the most talented writers and artists in the industry — including Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, Paul Chadwick, Joe R. Lansdale and Paul Pope — to try their hand at the character, publishing a series of original Spirit stories in 1996-1997.

In 2008, Frank Miller brought the character to the silver screen in a feature film starring Samuel L. Jackson as the twisted villain The Octopus, Scarlett Johansson as the femme fatale Silken Floss, and Eva Mendes as the serial killer Sand Saref, the Spirit’s childhood sweetheart and one of the only people to know his true identity.

The film was a major bomb, vanishing from theaters in weeks and effectively ending Frank Miller’s career as a director.

More successful was DC Comics, who revived and updated the character and brought him into the DC Universe with an ongoing series in 2007. The new version was written and penciled by Darwyn Cooke (and later Mark Evanier and Sergio Aragones, and a series of artists); it lasted 32 issues.

DC maintained The Spirit‘s reputation for excellent covers, including this sharp piece of the Spirit in the rain.

On the 94th anniversary of his birth in 2011, six years after he died, Google honored Will Esiner and his most famous creation by using an image of The Spirit as its logo.

With so many reprints out there, it’s not hard to find a few if you’re interested. I recommend starting with the Kitchen Sink editions; they’re high quality and relatively inexpensive. I purchased 14 issues in pristine shape on eBay last month for just $1 each.

Good hunting.

I was first exposed to the Spirit in essays in Jules Feiffer’s The Great Comic Book Heroes and Jim Steranko’s History of Comics. They spoke of Eisner with such awe and reverence, that when the Warren reprint books showed up in my local drugstore, I eagerly bought them all – and wasn’t disappointed. Eisner was, I think inarguably, the greatest comic writer-artist ever. Look at a story like “Heat” from 1948 or 1949 – the Spirit chases a bad guy into an alley. The bad guy shoots him and runs off. the spirit lies there bleeding to death, too weak to speak, while Eisener shows us the life going on around him, oblivious to his plight: housewives gossiping from window to window above, as they hang thier laundry; kids playing ball at the alley’s entrance; people strolling by on their way to work – and all the time, the voice of the radio giving bulletins on the rising temperature, as Central City has a record-breaking heat wave. The spirit is finally discovered, of course, by a kid looking for his ball. Eight pages (eight!) of brilliance, presented with ruthless economy. (Eisner was the least self-indulgent comics man alive – he just didn’t have room for it). Now look at what DC or Timely (Marvel) was publishing at the time. Their stories have their charms, of course, but they’re children’s stories, in conception and execution. “Heat” is a story for grown-ups. No one would do anything like it for twenty years. No one. Eisner was that far ahead; in fact most comics still haven’t caught up with him. And don’t get me started on the Frank Miller movie. It was simply a disgrace, and if Miller had any integrity he would issue a public apology (most of all to Eisner’s family) and retire from public life. If only.

EMc,

You said more about Esiner’s talent and impact in one paragraph than I did in 1,200 words. And you said it better, too. Well done!