Magic, and Miracles: An Interview with Bruce McAllister

Bruce McAllister lives in idyllic old town Orange, California. Outside his 1914 craftsman-style home, wild parrots squawk as they fly overhead from sweet gum tree to palm tree to an aged church bell tower in the distance. Inside, the home is neat and sparsely furnished. The only semblance of clutter is in McAllister’s writing office, where the desk is smattered with a few sheets of loose-leaf paper, and where along the sidewall, piled on top of a fold-out table and in plastic bins beneath it, he keeps his cobble collection. These fossil-riddled rocks are from the Santiago Creek riverbed where he routinely walks with his dog Madge. Like the seashell collection he had as a boy — and which plays a prominent role in his newest novel, The Village Sang to the Sea: a Memoir of Magic — these cobbles are a reminder of the wonder in the world around us, “rationale mysticism,” as he calls it.

Bruce McAllister lives in idyllic old town Orange, California. Outside his 1914 craftsman-style home, wild parrots squawk as they fly overhead from sweet gum tree to palm tree to an aged church bell tower in the distance. Inside, the home is neat and sparsely furnished. The only semblance of clutter is in McAllister’s writing office, where the desk is smattered with a few sheets of loose-leaf paper, and where along the sidewall, piled on top of a fold-out table and in plastic bins beneath it, he keeps his cobble collection. These fossil-riddled rocks are from the Santiago Creek riverbed where he routinely walks with his dog Madge. Like the seashell collection he had as a boy — and which plays a prominent role in his newest novel, The Village Sang to the Sea: a Memoir of Magic — these cobbles are a reminder of the wonder in the world around us, “rationale mysticism,” as he calls it.

Similar to Brad Latimer, the protagonist in The Village Sang to the Sea, McAllister grew up in a military family and lived in Italy for a time. Like Brad, his hunchback teacher caught him writing a story one day and, rather than punish him, the teacher encouraged him.

When he was sixteen, McAllister became nettled with another teacher, this one back in the United States, who was overemphasizing the importance of symbolism in literature. In an act of annoyed defiance, McAllister wrote a now famous letter, which he sent to 150 authors, including the likes of Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, and Fritz Leiber, wherein he asked their thoughts on symbolism in their work and whether it was ever purposeful. To his surprise, the vast majority of the authors wrote back. “It was a miracle they responded,” he says.

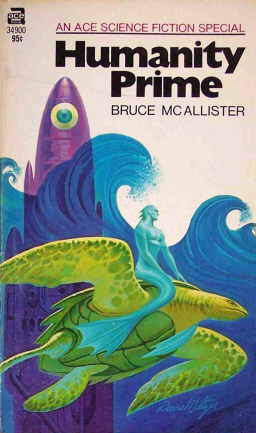

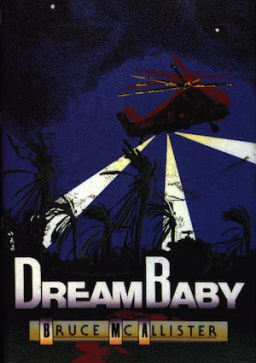

That same year, 1963, McAllister had his first story published in IF magazine. He was only sixteen. It took him writing twenty new stories to land his next publication, but the setback didn’t deter him. He continued to write short stories primarily, but also a few novels, including Humanity Prime (1971) and the critically acclaimed Dream Baby (1988). The latter took him fifteen years to write, during which time he interviewed 200 reluctant combat veterans about their ESP experiences and discovered how “meaningful coincidences” can illuminate the hidden magic in the world.

That same year, 1963, McAllister had his first story published in IF magazine. He was only sixteen. It took him writing twenty new stories to land his next publication, but the setback didn’t deter him. He continued to write short stories primarily, but also a few novels, including Humanity Prime (1971) and the critically acclaimed Dream Baby (1988). The latter took him fifteen years to write, during which time he interviewed 200 reluctant combat veterans about their ESP experiences and discovered how “meaningful coincidences” can illuminate the hidden magic in the world.

In 1991, McAllister developed a thyroid issue that went misdiagnosed and mistreated. The medications ruined his quality of life and kept him from writing for ten years, in essence leaving him to start his writing career all over again. McAllister is in a good place now, though. His wife Amelie is charming, and clearly a source of love and inspiration for him. He carries himself with an ease and confidence that can only be borne through overcoming adversity.

He’s also opened up more about the love and magic in his life. The son of a Navy marine scientist and a schoolteacher, he is an analytic, rationally minded person, and in past interviews has been reticent to discuss his beliefs on things like the ESP in Dream Baby. Not any more, though. He’s embraced the magic.

[Click on any of the images in this article for larger versions.]

Calcaterra: I just finished reading The Village Sang to the Sea, and it struck me how much the concept of rediscovering lost magic resonates in it, which is similar, I think, to what you do in Dream Baby. Is this a conscious or purposeful theme you like to explore?

McAllister: There’s a wonderful quote I once found: “Magic points to the magician and miracle points to something else.” That’s really what a lot of my fiction is about. In the Village Sang to the Sea, the village has magic, and it’s trying to change the boy, which is both a good thing and a bad thing. Brad is scared shitless of it, and at the same time, if he became that lizard at the end of it, well that’s transcendence.

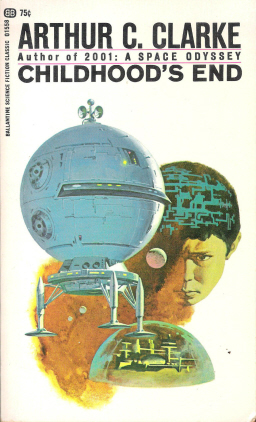

It’s a little like Arthur C. Clarke, whom I was influenced by early on. The brilliance of Childhood’s End is it starts with the idea that, “Oh my god, there are overlords and they’re alien.” And then, by the end of it, when human beings have transcended, they have become more alien — we hold onto the remaining overlord as being closer to us. He becomes our identification. It’s brilliant because it really becomes a study of what’s alien.

So in my book, while the boy is afraid of becoming a lizard, it’s because he’s afraid of no longer being human, including all of its pain. He’s not happy being human, but he wants to be a human. To me that’s really what human beings want. We’re quite willing to suffer. The human ego is the psyche’s embodiment of the body — it believes it can die, even though as long as we’re living it can’t die. This makes everything fear driven. Comfortable misery is preferable to fearful risk.

So in my book, while the boy is afraid of becoming a lizard, it’s because he’s afraid of no longer being human, including all of its pain. He’s not happy being human, but he wants to be a human. To me that’s really what human beings want. We’re quite willing to suffer. The human ego is the psyche’s embodiment of the body — it believes it can die, even though as long as we’re living it can’t die. This makes everything fear driven. Comfortable misery is preferable to fearful risk.

So I’m not saying Brad is ego driven, but he is making a commitment to being human, even though the village wants him to become a blissful lizard — and what’s wrong with that? It’s almost fear of Buddhism. “I don’t want to become enlightened because I don’t want to leave this world.”

That’s intriguing. I’ve never thought of magic in those terms. Where does this inspiration come from?

Wonder. My whole life has been stamped in wonder. Well, what is wonder? Wonder must be directed at something. It’s wonder at miracle, and it’s wonder at magic. Isn’t it? I was raised in the sciences, so if my writing, if my whole life, has been about wonder, is that wonder about science? Well, it can’t be about science that describes everything, that over manages it and reduces it mechanically to something. Wonder has to be at what science doesn’t know.

So in Village Sang to the Sea, the village is wielding magic, and there’s miracle in the book as well that has little to do with the village itself. In Dream Baby, the wonder that we feel is the wonder at the ESP. The ESP really operates as metaphor for what is in us — it’s serious and wonderful, and it can be used out of fear for darkness, or out of light. So magic in Dream Baby is both — if you have ESP, you can wield magic.

In a previous interview, you used the term “rationale fantasy.” Is that the same thing?

Well, all science fiction is rationale fantasy. But in the kind of science fiction I write, there is a transcendental element. There is magic-wielding in people — it can be supernatural or science fiction — and at the same time there is miracle. And let me be clear, I don’t mean miracle in the sense it’s a religious miracle. It’s the miracle Einstein talked about when he said, “We must achieve a cosmic religious feeling.” It’s the sense that there is something beyond what we know.

There are two types of scientists. One kind sees everything as knowable and rationale, so there is not anything beyond what we know. The other kind of scientist knows that if yesterday he did not know everything, then today he doesn’t know everything. How could he? That’s me. I have rationale mysticism. If in the past we didn’t know everything, then today we don’t know everything, and chances are we will never know, therefore there is something beyond what we know.

There are two types of scientists. One kind sees everything as knowable and rationale, so there is not anything beyond what we know. The other kind of scientist knows that if yesterday he did not know everything, then today he doesn’t know everything. How could he? That’s me. I have rationale mysticism. If in the past we didn’t know everything, then today we don’t know everything, and chances are we will never know, therefore there is something beyond what we know.

That creates for me a sense of wonder. The irony is, that’s what science fiction has been doing all along, and yet there can be a real hostility toward any spiritual or transcendental dimension in science fiction. Is science fiction atheistic or spiritual? We’re extrapolating into a future we don’t know, we’re using our minds, so is it atheistic because we’re being rationale or is it an exploration of the unknown? There’s a central paradox to science fiction, which is wonderful. Einstein’s model of the universe sounds an awful lot like Buddhism.

That makes a lot of sense, and I can see it in your work. Your treatment of the magic in The Village Sang to the Sea is done much less in a fantasy mode, and more so in a magical realism mode, where the magic, while fantastical, is never questioned and is simply part of the fantastical world where Brad lives. Was this a stylistic choice on your part, or is it a reflection of your view of the world and magic’s place in it?

In The Village Sang to the Sea, there are two kinds of writing. One is the memoir portion coming out of myself naturally, which is used to trick the reader into accepting the fantastic element as reality based, which is different from traditional fantasy. And then there are the fable-like parts that Brad writes. So, yeah it does have that slipstream overlap, but no I didn’t purposefully do that. I just wrote it. There are some writers who can consciously write in prescribed genres, but I just can’t do it. I’m so touchy feely, I can’t have that distance. Probably self-absorption or something (laughing)!

Many authors point to novels, comicbooks, or movies that inspired them as kids to go off and write, and you mentioned Arthur C. Clarke, but I get the sense from your writing that real life experiences played just as large a part, if not a bigger part, in forming your imagination. Am I right? Were there certain experiences in your life that have molded your writing?

Yes, but I’m always hesitant to talk about it. Personally, I’m fascinated by contextualism. I took my first college writing course and discovered I was not interested in the long political poems written 300 years ago, but I sure was interested in the fact that Milton was going blind and that his work became less visual and more aural. I was interested that Pope got his ideas while sitting in a stained glass grotto. It was the stories behind the stories that drew me in. But I’m not sure most readers are like that in our genre.

But to answer your question, yes, indeed we had a one eyed maid when I lived in Italy. Indeed we had a hunchbacked teacher with a lisp who caught me writing one day and instead of getting angry with me was nice. Indeed the hills crawled at night with vipers. Indeed there was a village not far from Lerici with little doorways too small for a tall man, with red hammers and sickles on the doors. How could you not feel wonder? How could you not feel miracle? Now part of it, of course, is the age. Except for me that it keeps happening.

You and I talked back in the Fall at the Big Orange Book Festival, and you mentioned that in looking for a publisher you were having a hard time deciding who the target audience is for The Village Sang to the Sea. Having read the book myself now, I very much get the sense it’s aimed at adults to remind us about the magic we’ve forgotten living in modern society. Was this one of the aims of the book?

You and I talked back in the Fall at the Big Orange Book Festival, and you mentioned that in looking for a publisher you were having a hard time deciding who the target audience is for The Village Sang to the Sea. Having read the book myself now, I very much get the sense it’s aimed at adults to remind us about the magic we’ve forgotten living in modern society. Was this one of the aims of the book?

Absolutely. That’s what I wanted to do in the book because I happen to believe it. I believe that, yes, we tend to lose wonder and a sense of magic and miracle in our own lives as we get older and there’s no reason for it. In Brad’s case, he continues the magic by writing, and my own life has been the same.

Is that the main source of magic in your life now? Through writing?

Partly yes. I seem to be have born as a storyteller, but it’s still drawn from my sense of wonder in real life. A well-known example would be the symbolism letter I sent out in high school. I view the fact that these famous authors responded back to me more as a miracle than I do as “my magic.” Other people view it online when it’s trending now as, “Oh my god, this sixteen year old reached out and made it happen!” No, I view it as — well, first of all I was a little bit cranky about my teacher and the class — but mostly I view it as, “Oh my god, those writers answered!” So what is magic? It’s not just a lens, it’s also having faith that the universe will deliver.

How did that play out in writing Dream Baby, where it was so much based on interviews and research?

Dream Baby is the most collaborative thing I’ve ever worked on. I didn’t serve in Vietnam, but really wanted to know it, so I had to rely on thirty intimate consultants. The writing of this book reached the point where, if I needed a character, the character would call me. It was freaky. But those things happen, I believe, when we are deeply doing what matters to us and what is profound, so that’s another form of miracle. Synchronicity.

I was telling my father, who fought in Vietnam between 1966 and 1967, about the premise of Dream Baby and he told me a story he’d never told anyone before, about a dream he had after returning home from the war. He was sleeping in his own bed, and somehow through this dream, he experienced a sapper attack in a Cam Ranh Bay convalescent hospital that was really happening that very same moment. Do you get readers and people coming up to you to tell you about their similar experiences?

Well, speak of synchronicity! Absolutely. I don’t hear those stories as much as I used to, but yes. That’s called spontaneous anecdotal data. In fact, what inspired this book was oral history of just that sort. The guy who really got me started on the book, was a guy I met. I didn’t know at the time that he had an HK assault rifle in his bag and he was the bodyguard for the head cocaine dealer in San Diego, so I was just talking casually, and I said, “What’s it like in the war?”

“Well, I was kicked out of special forces for slugging a sergeant and I ended up in the 101st Airborne,” he said, and then after a pause: “Yeah, the world would slow down and stop and I would… I guess you could call it floating out of my body, and I’d find the snipers and kill them. They would turn blue.”

At first, I was just, “Cool, I like it!” If I’m going to write science fiction, I don’t need to know if it’s true or not. But then I got to know him. And I got to know that what he was saying about everything was true. The CIA had indeed approached him, twice. He asked them if they wanted to know how his ability worked, and they said they didn’t care, they just wanted him working for them. And then over the years I met Navy Seals who had similar things happen. You hear all these outrageous things, and then they become very real.

That sounds a little like the way I’ve heard you describe ESP itself in other interviews.

Sure. The best research on ESP shows that ESP comes from what you call psychodynamic need — you can’t control it, therefore you cannot control it in the lab, you cannot replicate it. The stories in ESP research are just hilarious, because you can’t control any of that.

And that’s sort of how the book came together too. I interviewed 200 people, either face to face or by mail, and it’s also based on actual contingency plans to end the Vietnam War that have still not been made public, but have been alluded to in Nixon’s memoirs, and that has to do with whom my consultants were. I had not been in the war because I was going to college, but I wanted to understand the war. My sense was that both the political left and the right had not told us the truth. And I think I had survivor’s guilt — guys had gone in my place and I was starting to meet them. I initially assumed people would not want to talk to me, having avoided the war, but that wasn’t the case. I was interested in their story and that trumps everything.

For my main character, I had already written Mary, and then I found the real life her in an oral history. I contacted her, and her name was Jill, and she was exactly the same as my character — nurse, Catholic, the same voice. When I pointed it out to her, she agreed, and she said, “By the way, I’m a science fiction fan. Let me know if you’d like me to consult on your book.” For me, that’s where the writing and real life coincide. Synchronicity is a funny thing. You have to believe, as Jung said, that there are meaningful coincidences beyond explanation. Mathematicians would say, well you don’t have a big enough sample. But that’s not what being a human being is about.

Crazy. All right, change of subject. How long have you lived here in Orange?

For three years now. Amelie and I lived in Redlands for years, where I taught university, but we moved out here and it’s great — it reminds us of old town Redlands. And coincidentally, Jim Blaylock lives here, we ran into Tim Powers the other day at the local store.

You sensed that I was leading into talking about them! I know the two of them have been in the area for a long time and used to hang out with Phil Dick. Did you know any of them back then?

Oh yeah. Willis McNelly, who was a wonderful guy — a Joyce scholar at Cal State Fullerton who is probably best known for putting together the Dune Encyclopedia — well, he took me under his wing. I was just out of UC Irvine’s MFA program in fiction, and he brought me in to teach science fiction where I ended up meeting K.W. Jeter, Tim Powers, and Jim Blaylock — the founding fathers of steampunk. But I was a couple of years older, so I remember encouraging Tim to send out what I believe was his first short story submission, to Ed Ferman at F&SF, because I knew he had talent. And then I was out of the field for ten years with no contact — I was very ill — and I come back and I see this poster of Tim Powers. He was practically famous! I felt like Rip Van Winkle.

Do you mind talking about your illness?

Not at all. Believe it or not, it played a role in the whole spiritual evolution of my life. Basically, I was low in thyroid, but the local doctor sort of haughtily refused to believe it and put me on medications so nasty that my organs were starting to shut down. Eventually, after about six months after I had to leave teaching at the university, I found a team of doctors who figured out the real problem. Within another six months I was off all the medication, but one of them was so bad that when I got off it I was like a lightning strike patient.

Exactly. I was a mess, but I was on my way back to healing. I started writing again. Maybe this is too much information, but I unconsciously used writing to re-wire my brain. Doctors have told me that. I couldn’t think past the first paragraph, so the first things I wrote were prose poems. And they got longer and longer, until finally my first piece to get published was a little fable. So yeah, I used the one thing I can’t not do, storytelling, to remake myself. I didn’t know what I was doing at the time, of course. I was just trying to stay alive. I still can’t believe Amelie hung in there through it all.

There were a lot of changes in those ten years, but they were great to see. All these writers I knew before had won awards and their careers had moved forward. And there was Tim, famous! So that was very strange, but again, that’s sort of been my life. I mean, to live in Lerici as a kid… And even when I was on the medication… a talking rattlesnake in the upper desert of Calico basically showed me — and I was not hallucinating, I was quite aware I was generating the dialogue because one of the meds I was on was a brain energizer, which makes you fearless — and the talking snake led me to the oldest portable art in North America. So how can life not be full of magic and miracle?

The oldest portable art?

Yeah, it’s a very crude reclining Ice age bison. It’s like a proto effigy. Think a Navajo effigy. It’s probably 15 to 20 thousand years old. I originally showed it to four paleontologists in the area and they all said, “It looks like a reclining Ice age bison, but as far as we know there weren’t great herds of them here.” And then last year, they discovered them — evidence of the bison. So, that’s wondrous too. Sure, you have to be interested in what the wonders are, and some people aren’t. But I am. Where we live now, I take the dog out and we go to Santiago Creek and look for fossils — cobbles. There’s a layer of Miocene sandstone the creek cuts through and there’s a prehistoric whale, its bones spread out over three or four hundred feet. Isn’t that cool?

So yeah, I’m a geek, and the feelings I have about these things in life are no different than the fiction I write.

[…] Aeon Press in 2013, has been interviewed by Garrett Calcaterra of Black Gate magazine. Check out Magic, and Miracles: An Interview with Bruce McAllister, and here are the opening […]