The Uses of Ghosts

While Black Gate readers may (fairly) view me as a sword-and-sorcery writer, thanks to the Tales Of Gemen the Antiques Dealer, a good many of those who have stumbled across my fiction might (fairly) think of me as a horror writer. Since I never expected to fall into that particular category, I’ve been doing a good deal of soul-searching as to the value of what I’m up to – the value, as it were, of basing so much of my tale-spinning on the supernatural instead of, for example, “real life.”

While Black Gate readers may (fairly) view me as a sword-and-sorcery writer, thanks to the Tales Of Gemen the Antiques Dealer, a good many of those who have stumbled across my fiction might (fairly) think of me as a horror writer. Since I never expected to fall into that particular category, I’ve been doing a good deal of soul-searching as to the value of what I’m up to – the value, as it were, of basing so much of my tale-spinning on the supernatural instead of, for example, “real life.”

Dare I take this moment to point out that an entirely different set of readers might quite reasonably think of me as a writer of literary fiction? Yeah, I wear that hat, too.

This odd combination of multiple caps has led me to the following conclusion: ghosts are a tool in the writer’s toolbox, as specific as more established weaponry like setting, length, voice, and theme.

Without further ado, I offer my list of why Things That Go Bump In the Night have worth. I don’t expect this to be an exhaustive list, but I trust that I have made a good start. Perhaps you, gentle reader, will be inspired to add to the till?

Ghosts test our courage.

Most great stories test how “ordinary” people behave when under extreme duress. Ghosts, then, provide a fulcrum by which writers may explore their heroes’ true mettle. When the local phantom yells “Boo!” the question of who flees and who stands her ground becomes immediate and urgent. Ghosts reveal character.

Ghosts are really useful for scaring people.

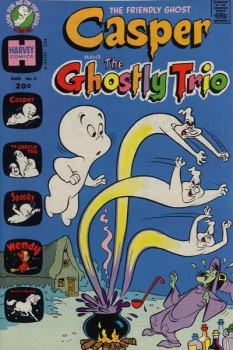

This surely centers on our (perfectly understandable) reticence to confront our mortality, and the alarming possibility that the afterlife either does or does not exist. Plus, spooks can say “BOO!” with really terrifying intensity. (If you doubt me, grab a back issue of Casper the Friendly Ghost and check out the Ghostly Trio.) Also, because revenants and haunts exist outside the day-to-day laws of the universe, they threaten we poor mortals with the possibility of very real and possibly gruesome harm. Anything that hails from beyond the safety of our various universal constants (the electron charge, time flowing only one way, etc.) is inherently terrifying. If inducing fright in readers is one goal of any given writer, it follows that the inclusion of a specter might be a jolly good way to do it.

Ghosts suggest a halfway point between life and death.

Now we get to the heart of the matter. Terror is an effect, not an endpoint in and of itself, except in the most shallow of fictions (although possibly H.P. Lovecraft would disagree). However, as soon as we take seriously the arrival of a haunt, we allow immediately for its status as that which comes from beyond the grave, as something that offers a glimpse behind the ultimate veil. Cheap scares be damned, any form of existence that defies death is exceptionally fertile ground for fiction. Thus, ghost-hunters pursue a kind of grail-like knowledge; to pin down the nature of a ghost is to glean at least something of humanity’s eventual fate, i.e., death. A communicative ghost (this sounds like a disease, mea culpa) might even be able to explain the afterlife, provide some sort of map, systematize both Heaven and Hell and every possible concept in between. Ghosts, then, could be more than just a source of wonderment; they could be a valuable fount of knowledge. True, that knowledge will remain strictly metaphorical, in that it is limited by the experience (and imagination) of the author, but this is equally of true of metaphysics. Why should ghosts be any different?

Ghosts, being scary, provide a mechanism for tension and release.

Build tension with fear; defuse it with laughter. Truly funny ghost stories are a rarity (although I’m staking my claim with The Skates, which I urge you to sample), but humor in horror films is very much the norm. When deployed effectively, as in An American Werewolf in London (1981), the yucks give viewers a much needed break from the terror of the stalking werewolf (not to mention a host of dreamscape zombies), only to leave us vulnerable to the next shock. After all, we can’t maintain our well-oiled defenses if we’re laughing. Remember what Donald O’Connor said: “Make ‘em laugh” — and then scare ‘em to death, immediately after, if possible. (Note: O’Connor never said that second part.)

Ghosts imply a past that requires rectifying.

Ghosts imply a past that requires rectifying.

Once again, the fictional engines spring to life. As with most detective yarns, the real point of a ghost story is often to put to rights some unattended wrong from the distant past. Why, after all, do ghosts bother with the tedious task of haunting? To draw attention to themselves, yes, or (better yet) to some past event that has been unjustly forgotten. Most likely this event takes the form of a crime, possibly of the criminal variety, or maybe a simple (!) crime of the heart. In either case, the advent of a needy spirit gives “we the living” a chance to make amends, and if that isn’t solid fodder for fiction, I don’t know what is. (Making amends: that’s certainly what drives my growing pile of Renner & Quist stories, the first of which appeared in Not One Of Us #46 back in 2012.)

Ghosts come in all shapes, sizes, and cultures.

Or, put another way, “Ghosts are people, too.” A specter from Namibia will be quite different, and have different needs, from its Danish or Uruguayan cousins. Thus, the term “ghost” turns out to provide virtually infinite variety – just like living people. What writer – or reader – can fail to get on board with that?

Ghosts are more fun than “the living.”

Let’s face it, ghosts are cool. It’s fun to describe ectoplasm, to set it in motion, to have a haunt slip through the keyhole or drift up the chimney. Spirits provide diversions that ordinary mortals cannot begin to equal – to a point. Great stories are always and without fail anchored in humanity, in explorations of “the human condition.” Sure, Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains” is all about a house, and there’s not a human character to be found, but that’s the point. The story resonates because it refracts human society through a clever and unexpected lens. Ghosts, then, can’t be the sole focus of a meaningful story: to really carry their weight, they must illuminate, hopefully in some surprising way, a part of our ongoing mortal story, preferably in an entirely unexpected manner. (Note: ghosts could certainly be the only characters in a given story, but if they don’t in some way relate to the experience of this mortal coil, the story will not fully resonate or, dare I say it, come to life.)

chimney. Spirits provide diversions that ordinary mortals cannot begin to equal – to a point. Great stories are always and without fail anchored in humanity, in explorations of “the human condition.” Sure, Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains” is all about a house, and there’s not a human character to be found, but that’s the point. The story resonates because it refracts human society through a clever and unexpected lens. Ghosts, then, can’t be the sole focus of a meaningful story: to really carry their weight, they must illuminate, hopefully in some surprising way, a part of our ongoing mortal story, preferably in an entirely unexpected manner. (Note: ghosts could certainly be the only characters in a given story, but if they don’t in some way relate to the experience of this mortal coil, the story will not fully resonate or, dare I say it, come to life.)

Ghosts are reassuring.

This goes back to my earlier point, “Ghosts suggest a halfway point between life and death.” The very fact that they come from beyond the grave is “proof” that there is at least something after death. In their insubstantial way, spirits support virtually any religious tradition, and allow for the ongoing hope that there’s more to come, an impending second act. In the moment, they may terrify – “Boo!” – but once we victims stop to think about our ghostly encounter, whether of the fictional variety, or when exploring that long-abandoned (and very dark) mine shaft just down the road, the net result of meeting up with a ghost is a metaphysical sigh of relief. This, too, plays into the hands of the storyteller. A visitation from beyond can provide closure for a story’s mortal characters – or, earlier on, open up a line of enquiry.

Ghosts can serve a direct plot-related function.

Consider the opening of Hamlet, in which the ghost of Hamlet’s father delivers a message that all is not well in the fish-stalls of Denmark. Without that apparition, the plot of the play would never get rolling. Or consider another Shakespearean outing, MacBeth. Banquo’s ghost spurs MacBeth to greater fits of madness and megalomania. In my own short story, “The Experts,” from All Hallows 40 (now long out of print), my heroic trio of starving gold miners requires medical advice, and it’s a quartet of poker-playing ghosts (physicians, every one) who provide the information the miners require. In each of these examples, the story being told is more than simply amplified by the judicious use of the non-corporeal, it is in fact pushed forward by supernatural means. The ghosts in question become necessary engines of plot, and without them, the story fails.

Ghosts can reveal a character’s interior (mental) state.

Ghosts can reveal a character’s interior (mental) state.

Not all literary ghosts are real. Is there a supernatural visitation in The Turn Of the Screw? Explanations differ. In creating my troll and Warcraft-infested play, Ten Red Kings, my hero, Margot, receives regular visitations from her dead sister, Courtney, killed in a highway wreck. Courtney is real enough in that an actor embodies her, but she’s not present for anyone else; she appears to Margot and Margot alone, and only because Margot desperately misses her big sister. Dramatically, allowing Courtney stage time gave me a method by which I could explore the depth of Margot’s loss (and her resultant addiction to on-line gaming) without forcing the poor girl to actually say, “Gosh-golly, Courtney, I really miss you and it’s totally messing with my head and I’m really depressed.” Ghosts then, like other dramatic personae, can obviate the need for bald exposition––and that right there would be enough to justify keeping the arrow of phantoms in my writerly quiver on a permanent basis.

Now then. Your turn.

How do you position ghosts in the endless realms of the written word?

Any favorite examples?

‘Til next time.

Dream hard.

Write harder.

Onward!

Mark Rigney has published three stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library: ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.” In other work, Rigney is the author of ”The Skates,” and its haunted sequels, “Sleeping Bear” and Check-Out Time, forthcoming in 2014.

[…] this week Mark Rigney put up an interesting post on the (narrative) uses of ghosts, and suggested a number of plot and thematic functions a ghost […]