Insanity in Pictures

Though I can’t be completely certain, I think the first time I encountered the name of H.P. Lovecraft was sometime during the course of 1980, not long after I’d discovered Dungeons & Dragons. The thin blue rulebook contained inside the Basic Set included a single reference to “Cthulhu” as a deity alongside Crom and Zeus (two names I already knew). Back in those days, hobby shops were ground zero for the burgeoning roleplaying hobby. Bearded wargamers, nerdy college kids, heavy metal-loving teens, and fantasy fans of all sorts rubbed shoulders in these peculiar little stores, swapping stories of their characters and campaigns, as well as holding forth on a variety of topics. To a young person such as myself, hobby shops were amazing places filled with amazing people, whose company I sought out as often as I could.

Though I can’t be completely certain, I think the first time I encountered the name of H.P. Lovecraft was sometime during the course of 1980, not long after I’d discovered Dungeons & Dragons. The thin blue rulebook contained inside the Basic Set included a single reference to “Cthulhu” as a deity alongside Crom and Zeus (two names I already knew). Back in those days, hobby shops were ground zero for the burgeoning roleplaying hobby. Bearded wargamers, nerdy college kids, heavy metal-loving teens, and fantasy fans of all sorts rubbed shoulders in these peculiar little stores, swapping stories of their characters and campaigns, as well as holding forth on a variety of topics. To a young person such as myself, hobby shops were amazing places filled with amazing people, whose company I sought out as often as I could.

There was a strange camaraderie among the hobby shops’ patrons – or so it seemed to me anyway. We were all a little strange by the standards of the time, taking interest in things that were still many years from mainstream recognition, let alone acceptance. Consequently, the usual distinctions of age didn’t matter much and I regularly found myself chatting with people years older than myself about gaming and fantasy and science fiction. I can’t begin to convey what a big deal this was to me. I was a shy, bookish sort and didn’t make friends easily, yet here I was gabbing with teenagers and university students as if we were old comrades.

That’s when I heard someone mention Cthulhu again and, callow youth that I was, asked just who (or what) Cthulhu was. Little did I know that that innocent question would lead to a lifelong interest in the life and works of H.P. Lovecraft.

Like a lot of Lovecraft fans, I have an almost-masochistic desire to see the Old Gent’s works adapted into films or television, despite the fact that, to date, this has almost never been done successfully. The best cinematic adaptation in my opinion has been the silent movie version of The Call of Cthulhu, released in 2005. I’m not entirely sure why Lovecraft has proven so difficult to adapt, since many of his stories have rather straightforward plots. Among these is one of my favorite tales, the 1936 novella, At the Mountains of Madness, which tells the story of a Miskatonic University-sponsored expedition to Antarctica that ends in disaster. Though long and filled with a lot of first-person exposition, this story doesn’t feature multiple, nested narratives or extensive flashbacks. Moreover, there’s a fair bit of action in At the Mountains of Madness; the story doesn’t take place primarily inside the protagonist’s head as he ponders the mind-blasting nature of reality.

I’m apparently not alone in thinking this, since Mexican director Guillermo del Toro wrote a screenplay for a movie adaptation and has been attempting to convince a studio to finance it since 2006. At one point, Tom Cruise was attached to star in it and James Cameron was to be its producer. Nothing much has come of this, however, and At the Mountains of Madness languishes in development hell, probably never to escape. Despite the high profiles of the people involved, I’m not particularly broken up about the likely collapse of this effort. I’ve come to assume that Lovecraft adaptations (like those of Robert E. Howard) will be terrible, no matter who’s behind it, and would rather that no movie be made than a bad one.

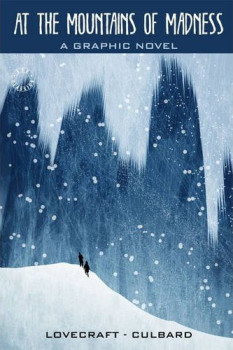

But movies aren’t the only medium into which Lovecraft might be translated, as I.N.J. Culbard‘s graphic novel version of At the Mountains of Madness proves. I am not a habitual reader of comics and never have been. Consequently, I generally only read comics after someone else recommends them to me, which is why I only just recently learned of this adaptation, even though it was published almost four years ago. I’m very glad that I was introduced to it. In 124 pages, Culbard succeeds in re-telling one of Lovecraft’s best tales in a fashion that’s both engaging and true to its source. That’s harder than it sounds. I place a high priority on fidelity to one’s source material, but I also recognize that translating between one medium and another is fraught with difficulties. Too slavish a fidelity may result in something that’s ponderous or, worse yet, boring.

But movies aren’t the only medium into which Lovecraft might be translated, as I.N.J. Culbard‘s graphic novel version of At the Mountains of Madness proves. I am not a habitual reader of comics and never have been. Consequently, I generally only read comics after someone else recommends them to me, which is why I only just recently learned of this adaptation, even though it was published almost four years ago. I’m very glad that I was introduced to it. In 124 pages, Culbard succeeds in re-telling one of Lovecraft’s best tales in a fashion that’s both engaging and true to its source. That’s harder than it sounds. I place a high priority on fidelity to one’s source material, but I also recognize that translating between one medium and another is fraught with difficulties. Too slavish a fidelity may result in something that’s ponderous or, worse yet, boring.

This graphic novel neatly avoids such sins for two reasons. First, Culbard deftly pares the story down to its essentials, in terms of action, dialog, and exposition. The story thus moves along at a fairly brisk pace, something that cannot be said of the novella, love it though I do. Second, the artwork, which, to my mind, recalls Hergé’s Tintin series, contributes greatly to a sense of narrative motion, which is vitally important in an adaptation of a long and complex story like this one. Furthermore, the artwork suits the subject matter perfectly, recalling as it does (at least to me) stories of late 19th and early 20th century exploration in the still-dark corners of the globe. There’s a brightness to it that also nicely contrasts, both esthetically and dramatically, with the unfolding events of At the Mountains of Madness. Even though I already knew the plot intimately, I found Culbard’s strong, clear, almost innocent, illustration style gave it new life, something I didn’t think possible.

Culbard has done comic adaptations of two other Lovecraftian tales (The Shadow Out of Time and The Case of Charles Dexter Ward), as well as A Princess of Mars, which is another favorite novel of mine. Based solely on his work on At the Mountains of Madness, I’ll certainly be checking the others out when I get the chance.

If you’re interested, Culbard was a guest co-host on the H. P. Literary Podcast when they covered At the Mountains of Madness. He had some very interesting insights into the story since he had just finished this graphic novel. Good stuff!

This looks great! Have added it to my xmas wishlist 🙂

[…] in November I was very intrigued to read James Maliszewski’s review of a recent comic adaptation by I.N.J. Culbard. Here’s […]