Two Blasts from a 70 mm

I spent a large chunk of the evenings this weekend watching two films in 70 mm prints on the large screens of grand old Los Angeles cinemas. The timing was right for the prodigious L.A. revival screening community to drag out the mega-sized celluloid for enjoyment in Gargantua-Vision: it was Oscar weekend and everybody was talking and joking about Avatar, even if they knew Hurt Locker was going to win Best Picture. Which it did. (I think District 9 should have won, but didn’t delude myself for a moment that this would happen. But Jeff Bridges, huh? Pretty cool. Kevin Flynn has an Oscar.)

The term “game changer” was kicked around a lot regarding Avatar when it first premiered. Then a massive backlash set in even as the movie steamrollered box office records toward a $750 million domestic gross. Avatar most certainly is a game changer as far as 3D is concerned; we’re going to drown in the format for the next two years, and the huge opening of Alice in Wonderland, which was rigged for 3D in post-production, will only prolong this. But Avatar as a big-screen visceral experience is not so much the New Reality as it is a Throwback to the widescreen explosion of the 1950s that carried into the 1960s. Plenty of rotten films got spectacular treatment in Cinemascope, Vista Vision, Technirama, Todd-AO, Super Panavision 70, etc. Plenty of very good films as well. And handful of masterpieces that still define “pure cinema,” the art form of the enormous moving image.

I watched two of those ‘60s classics this weekend, both shot in Super Panavision 70, a competitor to the Todd-AO 70 mm process. The first movie was at the Aero Theater in Santa Monica, and the second at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood, two blocks from the Kodak Theater where the Oscars were to be held in less than twenty-four hours. (And let me tell you, parking and even crossing the street was insane, even for Hollywood and Highland.) Both theaters run under the aegis of the American Cinematheque, a non-profit organization promoting the art of film. I’d seen both movies before, and one previously in a 70 mm screening. But at a time when I was already a’weary of Oscar 2010 talk, I wanted to immerse myself in some awesome hugeness of the 1960s. I wanted to ride through the Arabian sads to attack Aqaba, and travel to Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite.

You can probably guess now which movies I saw.

I’ll start with the second movie I saw first, since it’s not as personally important to me, although this was the first time I had watched it in a theater.

When people quip that “They don’t make ‘em like they used to,” I’m certain they’re talking about Lawrence of Arabia. They can’t mean anything else. This film is the epitome of that old saw.

I had never seen Lawrence of Arabia in a theater before, which makes me wonder if I can say that I’d seen Lawrence of Arabia at all. I first watched it in the ‘80s, cropped on TV, and wondered why anybody thought it was a big deal. I saw a widescreen laserdisc of the 1989 restoration, and that improved my appraisal, but I still didn’t get why people like Martin Scorsese would seemingly throw themselves on a scimitar in the cause of this movie.

I get it now. Astonishing film. Television, even widescreen ones, simply murder this movie.

Swords and guns in the desert . . . even if Lawrence of Arabia was mere spectacle about the Arab revolt in World War I with no interesting characterization, great performances, or genius scripting, it would still grab at the imagination for its panorama of the desert and charging camels and horses. The long pan of the Arab tribes smashing into Aqaba, the slow rise of the sun over the knife edge of the sands, Omar Sharif gradually emerging from the waves of heat, the single-take destruction of the al-Hejaz railway—all visual marvels. But there were many other widescreen spectacles of the same scope that haven’t survived as well. Lawrence of Arabia has the “everything else” to go with looking great.

Lawrence of Arabia was a smash hit in 1962, and picked up the Oscar for Best Picture. But star Peter O’Toole was bizarrely snubbed in favor of Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mockingbird. I like Gregory Peck in that picture, but now that I’ve seen Lawrence in all its Super Panavision “oh wow” glory, I can’t understand how O’Toole got passed over.

That is what really struck me about seeing David Lean’s telling of T. E. Lawrence’s involvement in the revolt: the performance of Peter O’Toole. Given an enormous screen, the actor’s embodiment of this complex figure is spellbinding. The tics, the silences, the stares, the grandiose gestures, the body language. None of this came through to me before like it did when O’Toole loomed over me on a sixty-foot screen. When Lawrence announces “Nothing is written” as he rides back from the remarkable rescue of Gasim from the Anvil of the Sun, I felt a shudder like nothing the movie had ever given me before. When the broken Lawrence begs General Allenby “for a job any man can do,” I felt devastated to see this man who had shoved himself to godlike heights brought down to a quivering mess. O’Toole’s T. E. Lawrence finally spoke to me . . . the therefore, the film did as well.

Seeing Lawrence of Arabia at the Egyptian, a theater built in 1922 in full Middle Eastern chic, underneath a proscenium of scarabs and serpents and a sunburst of Ra, added an tangible extra dimension to the film that I could never get from 3D.

And the night before I saw Lawrence of Arabia. . . .

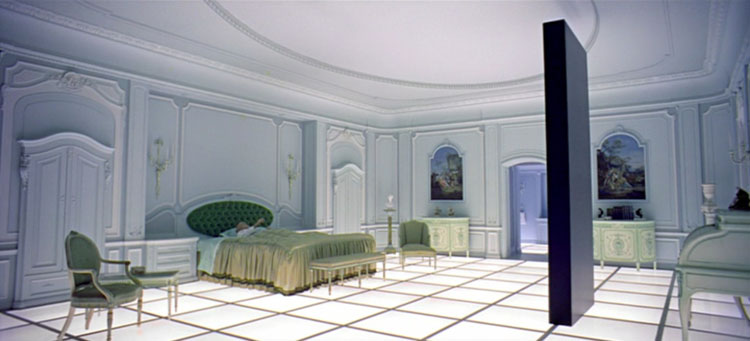

I don’t have an official “favorite movie.” I realized about a decade ago that trying to shoehorn a particular film into this spot wouldn’t achieve anything; there are too many that I love, on some days I love one more than another, and it constantly shifts depending on my mood. If I had to narrow down a short list to force a choice, 2001: A Space Odyssey would be one of the obvious and immediate candidate on it. In fact, it would be the earliest film from my life to enter this hypothetical list. I first saw the movie when I was eight years old when it showed on cable. Z Channel, I believe. I didn’t understand anything of what was happening, but I knew I loved it. And this was on a conventional-sized TV, in mono, and cropped. Think of how my opinion grew as I saw it in better formats and my mind matured.

I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey in a theater for the first time in the late ‘90s. It was a 70 mm print shown at the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood, in the days when the dome stood alone in a parking lot on Sunset Blvd. like a great alien intelligence had dropped an enormous golf ball that imbedded itself halfway into the asphalt. Now the dome is part of a large complex called the Arclight, but at least it remains preserved (it was almost demolished—evil! evil!). That screening is still, to this day, my favorite experience in a movie theater. I already loved the film, but this was epiphany. This was, as the original posters proclaimed, “The Ultimate Trip.” And it required no illegal substances to make it, just the price of a ticket.

I’m not going to detour into my interpretation of 2001, which would require a separate blog post all on its own and would be primarily an exercise in self-entertainment as there is no one single way to interpret the film. I’ll step away from analysis of the film’s panorama of human history and its relationship to technology and simply say that no other film gives me the same immersive experience, the same feeling of complete cinema, as 2001: A Space Odyssey. In grosser terms: I love this film so goddamn much it’s far beyond rational thinking. Any time, anywhere, if you asked me, “Would you like to watch 2001: A Space Odyssey?” I would grab an animal bone and smash in your skull, which is my fannish way of saying, “Yes!”

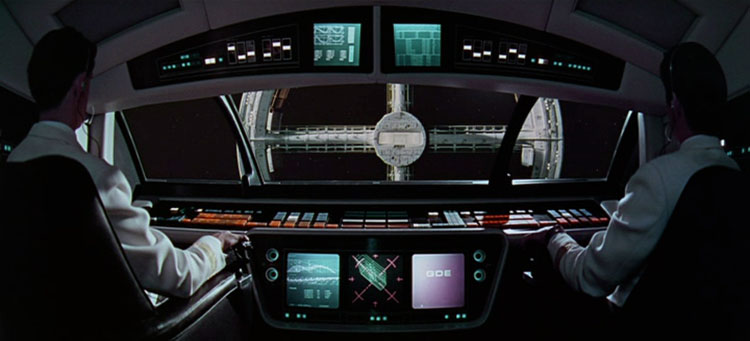

People who love the movie as much as I do—and they surrounded me on Friday night—know exactly what I’m talking about: there’s a rhythm to this primarily visual film, a tonality, that is hypnotic. Even the spoken lines, which are often considered “bland” and “wooden,” are completely perfect for us. I think the dialogue is brilliant. It’s simple, ordinary, bureaucratic, and 100% the right material for the movie, and thus a joy to hear. And the cast is ideally suited to their lines. Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood? Most believable astronauts in history. Douglas Rain? Nine hours in a recording studio and he became the most famous voiceover in history. Daniel Richter? No better ape, ever. William Sylvester? Now there’s a genuine space-age pencil pusher if I ever saw one.

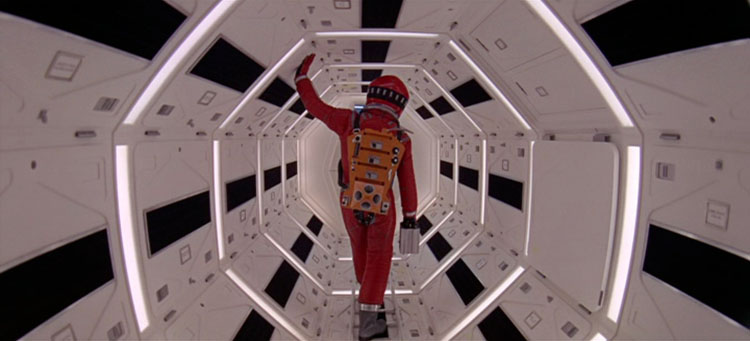

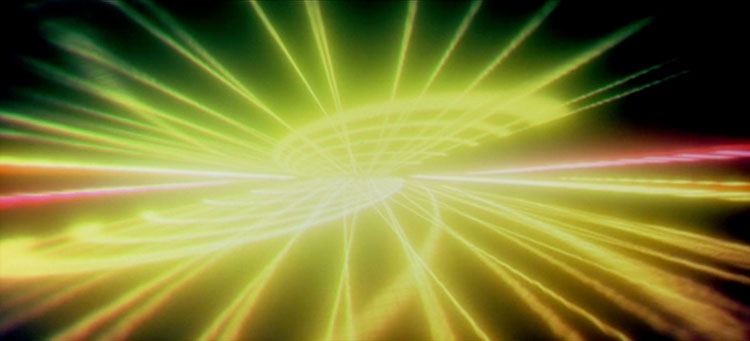

But the visuals are the meat and the bones of the film, and the visual effects are still “how the hell did they do that?” awe-inspiring today. It isn’t merely that the effects were executed with such realistic precision so much as the way they are orchestrated on the screen into complete movements like sections of an opera, a ballet, or an abstract dance performance. On 70 mm, the Stargate sequence will turn your head inside out, even if you have no clue in the multiverse what is going on. My Dad is the proof of this. He loves this film, and when he first saw it with me on the big screen in the 1990s, he turned to me afterwards and said, “That was amazing.” I asked: “Do you understand it?” He smiled and said, “Not one bit.”

You’ve probably guessed that I enjoyed my second 70 mm viewing of the film. Even if the print had some scratches and damage on it.

But I loved 2001 long before I ever saw it in its proper format. I adored the film on VHS, and on a 16 mm projection in college. I can’t say the same about Lawrence of Arabia, which I didn’t truly grasp as a masterpiece until Saturday night. What is it about 2001 that transcends even an awful format that should eviscerate it? Is it the grandness of its non-verbal ideas that provoke thought even if the image is far from grand? Or is it that the film’s uniqueness and controversy (yes, some very intelligent folks really can’t stand the movie) make it stand out no matter how it is presented?

I think it comes down to this:

Lawrence of Arabia: “They don’t make ‘em like they used to.”

2001: A Space Odyssey: “Even when they made ‘em like this, this didn’t make ‘em like this.”

“Dave, this blog post can serve no purpose any more. Good bye.”

I’m envious, I’ve still yet to appreciate either of these on the big screen. Great stills in this piece.

[…] as a great nod to one of cinema’s other epics, Lawrence of Arabia. (Appropriately, I once wrote a post combining 2001: A Space Odyssey and Lawrence of Arabia as examples of the power of immersive 70mm cinema, the ancestor of […]

I came across this page doing a Google Image search for “Moonwatcher”. You’ve hit on my 2 all time favorite movies. AND….they are both films that have to be seen on the BIG SCREEN (preferrably 70mm) to really grasp the power they can convey.

2001 – the ONLY movie I’ve ever walked out of……where NO ONE SPOKE A WORD WHEN LEAVING THE THEATER. A mind blower. And Lawrence of Arabic…..powerful story, and cinematography that is truly beautiful and astounding.