Excuse me, Are you Using that Plot Device?

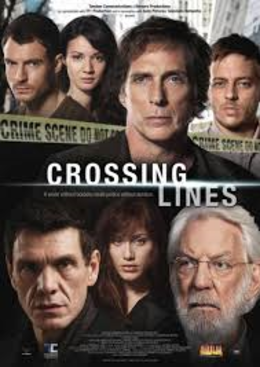

The other day, I was watching a new Canadian show that I’m not sure is even airing in the US called Crossing Lines. It stars, among others, William Fichtner and Donald Sutherland, and promises to be a kind of Agents of Shield without the Marvel universe – a group of police officers from different countries come together to solve international crimes as an arm of the International Court. So far so good, except for . . .

The other day, I was watching a new Canadian show that I’m not sure is even airing in the US called Crossing Lines. It stars, among others, William Fichtner and Donald Sutherland, and promises to be a kind of Agents of Shield without the Marvel universe – a group of police officers from different countries come together to solve international crimes as an arm of the International Court. So far so good, except for . . .

In the second episode, a tender moment occurs where two characters bond over similar family issues. They look warmly into each other’s eyes and promise to talk about it later. I call out “Dead man!” And of course I was right. One of them was dead by the end of episode, leaving the other feeling bereft. And leaving me rolling my eyes.

While “Dead man!” can be fun to play (as can “She did it!”) it’s a sad commentary on the state of narrative that these games can be played so often.

Okay, I hear you say, so it’s a plot device, and maybe it’s a bit overused (where “a bit” means I’m understating). Is that really so wrong? Yes, yes it is. The problem with this kind of thing is that because we recognize it, we feel manipulated, and when your viewers, or your readers, feel manipulated, you’ve lost them. You’ve reminded them that not only did you make this bit up, you’ve made all of it up. When your readers start considering the structure of the narrative, they’ve taken a step back from it. And bang, as they say, goes your willing suspension of disbelief.

We could argue that this kind of manipulation doesn’t happen as much in novels or short stories as it does in television and movies. Maybe not. Novels, for one, have time enough to make readers genuinely care about a character before she gets killed. And plot devices are actually useful things; both as readers and writers we love them, except when we hate them.

Some are so common that we don’t even notice them anymore – or at least we accept them as a literary shorthand. Unless the story is about a family relationship for example, all protagonists are literally or figuratively orphans. Like, say, both Luke and Leia Skywalker, Conan, Wonder Woman, both Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser. Superman. Batman. Frodo, and while we’re in that universe I might as well add Bilbo. Depending on the needs of the narrative, these characters have more or less stressful or meaningful reasons for being orphans, that have more or less significance in forming the protagonist’s character, which in turn moves the narrative forward. Think about the difference between how Superman and Spiderman approach their abilities, if you’re unsure what I mean.

Why is the orphan trope such a useful plot device? Sometimes it helps motivate the protagonist. Leia was already part of the Rebel Alliance, but it took the deaths of his uncle and aunt to motivate Luke to join up. Certain kinds of loss help explain why a character becomes a villain or a hero. But there’s another reason: it can simplify things for the writer. If the character has parents and siblings, those people, and the relationships their presence implies, have to be dealt with. If we don’t want that kind of complication added to the narrative – if that’s not where the story is – then it’s often best not to have those characters at all.

Why is the orphan trope such a useful plot device? Sometimes it helps motivate the protagonist. Leia was already part of the Rebel Alliance, but it took the deaths of his uncle and aunt to motivate Luke to join up. Certain kinds of loss help explain why a character becomes a villain or a hero. But there’s another reason: it can simplify things for the writer. If the character has parents and siblings, those people, and the relationships their presence implies, have to be dealt with. If we don’t want that kind of complication added to the narrative – if that’s not where the story is – then it’s often best not to have those characters at all.

Good complications – good plot devices – arise out of the protagonist’s character and circumstances. The bad ones generally arise out of the writer’s need to make something happen or to manipulate the emotions of the readers.

[Aside from the PhD in 18th-century literature: as far back as 1728 John Gay, in his play The Beggar’s Opera, satirized the manipulative plot device. It was typical in tragedies of the day to have the dying hero’s wife and children appear at the moment most guaranteed to bring a tear to the eye. Gay lampooned this overused device by having all of Macheath’s mistresses show up, one after another, babe in arms.]

Okay, so, orphan status, good/useful plot device. What are some bad ones? Anything that manipulates emotion, rather than letting the emotion arise naturally out of the situation. This includes the sudden and otherwise inexplicable bonding between characters who have nothing else in common (“dead man!”); and the hint of impending doom (“Three days to retirement” “The blue mage is the only person left who knows the secret of the device”) which is, as you realized, a variation of “dead man!”

Remember, it’s foreshadowing only if the readers don’t see it as such until after the event. If they notice it right away, it’s called telegraphing. Foreshadowing good, telegraphing bad.

The one I particularly dislike is the “If I tell, it will ruin everything.” Well, no. Actually, all it ruins is the badly conceived plot. The character has a secret she keeps from everyone, which turns out to be not such a problem once it’s finally revealed. I mean, it’s never “I’m the killer,” or, “I’m your father” – okay, sometimes it is that one, but you see what I mean. If you put the book down or walk out of the movie theatre saying to yourself, “Why didn’t they ask so-and-so?” or even “Why didn’t she just tell them?” you’re familiar with this plot device.

Don’t misunderstand me, the character may have an excellent reason for either not asking, or not telling, and in a well-written, carefully conceived novel/film/TV show, she will and the audience will be satisfied by it. But if she doesn’t, if the only reason for not telling, or not asking, is that it would ruin the story . . . that’s a bad plot device.

Violette Malan is the author of the Dhulyn and Parno series of sword and sorcery adventures, as well as the Mirror Lands series of primary world fantasies. As VM Escalada, she writes the soon-to-be released Halls of Law series. Visit her website: www.violettemalan.com

[…] to one of my favorite fantasy writers, Violette Malan, a bad plot device is “anything that manipulates emotion, rather than letting the emotion arise naturally out of […]

I recently read two books by the same author. Recognized the villain in the second one quite easily, once I saw the pattern.

Totally agree with you about mc and family! As for ‘If I tell, it will ruin everything’….

Coincidentally I was watching an old twilight episode on Youtube yesterday – ‘The Old Man in the Cave’, about a bunch of post-holocaust survivors in a small town who rely on the mysterious ‘old man in the cave’ to tell them what to eat and not to eat, where to plant their crops etc, and whose edicts are passed onto them via an intermediary, a Mr. Goldsmith. That is, until a sceptical James Coburn turns up and challenges their unthinking acceptance of Goldsmith’s claims. Goldsmith refuses to elaborate on the Old Man or how he is so well-informed. Coburn persuades the townspeople to eat food the ‘Old Man’ has warned them is contaminated, then to storm the cave. They find (surprise, surprise) a computer, which they destroy, again at Coburn’s instigation. Of course they all subsequently die apart from Goldsmith, who laments Coburn’s faithlessness before moving on.

OK, so maybe this is intended as an allegory for religious faith, but doesn’t really stand up to closer scrutiny (although Coburn acts his socks off and the episode as a whole is enjoyable), partially because the computer isn’t some philisophical abstraction but a real live computer* but chiefly because you’re left wondering why Goldsmith employed such an elaborate and unnecessary ruse in the first place; why not tell the townspeople the information was being relayed to him via a computer as opposed to some mysterious ‘Old Man’ from the get-go? Wouldn’t they more likely to accept a computer’s prognostications than the forecasts of somebody they never even get to see?

* no explanation is provided as to the computer’s origins.

Mary: that SO often happens. It’s worse with TV, of course, where the guest star is usually the villain

Aonghus: it’s possible that the reason the guy didn’t admit it was a computer is due to the era the episode came out. Computers were a new concept then, and more likely to terrify people (the machines are taking over! A computer took my job!) than reassure them.

Makes sense – especially given how they all subsequently destroy it!

[…] Last week I talked about how badly-used plot devices often arise out of the writer ignoring character and “making” something happen, often to manipulate the reactions of readers and viewers. You can avoid this by asking yourself some simple questions right at the start. Many of us start writing with character in mind, so we ask ourselves, “Given this type of person, what kind of interesting things can happen to her?” Even if you start somewhere else, however, one of the first questions you’ll have to ask yourself is “Whose story is it?” […]