Amazing, March 1961: A Retro-Review

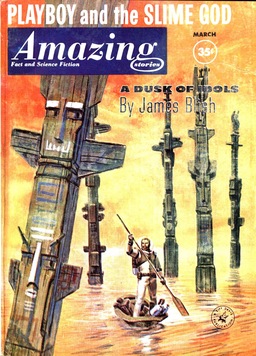

This is a pretty strong issue of Amazing, overall. Really strong list of authors. The cover is interesting – not so much the illustration, a decent and quite accurate Leo Summers painting illustrating James Blish’s “A Dusk of Idols.” What intrigued me were the words.

This is a pretty strong issue of Amazing, overall. Really strong list of authors. The cover is interesting – not so much the illustration, a decent and quite accurate Leo Summers painting illustrating James Blish’s “A Dusk of Idols.” What intrigued me were the words.

Sure enough, “A Dusk of Idols,” by James Blish, adorns the cover. Makes sense. But atop the title, we read “Playboy and the Slime God.” That’s an Isaac Asimov story. Wouldn’t you think they’d have promoted Asimov’s name? But no. I can’t figure that one out.

Interiors are by Summers, Ivie, Morey, and the great Virgil Finlay. The editorial is by Norman Lobsenz as usual, and it promotes the next issue – which is to be a special All-Reprint issue, consisting of classic Amazing stories selected by Sam Moskowitz. (Sigh … I know people defend his research, and I have no dispute with that, but I do dispute his taste.)

Anyway, the issue does seem to feature some significant stories – an early Bradbury, Eando Binder’s “I, Robot,” an ERB reprint, Nowlan’s Armageddon – 2419, and pieces by Starzl, Hamilton, and Keller. Lester Del Rey’s Fact Article, “Operation Lunacy,” essentially addresses the Mutual Assured Destruction doctrine, a little presciently, it seems to me.

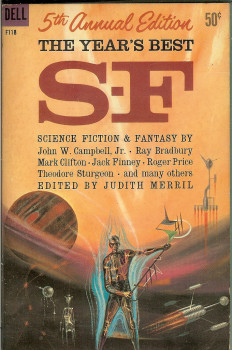

S. E. Cotts’s book review column, The Spectroscope, is rather harsh on balance towards two anthologies, Judith Merril’s The Year’s Best S-F, Fifth Annual Edition and Robert P. Mill’s Decade of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Cotts opens by complaining that “there are more kinds of anthologies than you can shake a stick at… of one particular author’s output, or from one particular magazine, or on one particular subject… year’s best, year’s worst, or the year’s zaniest.”

Of Merril’s book Cotts begins kindly enough: “As far as the stories are concerned, it is the best yet.” And particular praise goes to newer writers, Daniel Keyes for “Flowers for Algernon,” Carol Emshwiller for “Day on the Beach,” and “an English author, J. G. Ballard” for “The Sound Sweep.”

But then come the quite vituperative complaints. Merril, it seems (well, we know it’s true, because this is what Merril did!) included non-stories, from (gasp! Horrors!) places like The New York Times, and even a John Campbell editorial.

Cotts also complained (and here I have some sympathy) about Merril’s “constant sniping remarks about Kingsley Amis,” saying they make the book take “the tone of a high school yearbook.” [Apparently, Blish suggested that Merril was offended that Amis’s book New Maps of Hell didn’t mention her; others suggest that she was unhappy with Amis’s promotion of Frederik Pohl, from whom she had been rancorously divorced. It could simply have been the resentment many SF readers at the time felt towards an “outsider” pronouncing (even sympathetically) on the field.]

Cotts also complained (and here I have some sympathy) about Merril’s “constant sniping remarks about Kingsley Amis,” saying they make the book take “the tone of a high school yearbook.” [Apparently, Blish suggested that Merril was offended that Amis’s book New Maps of Hell didn’t mention her; others suggest that she was unhappy with Amis’s promotion of Frederik Pohl, from whom she had been rancorously divorced. It could simply have been the resentment many SF readers at the time felt towards an “outsider” pronouncing (even sympathetically) on the field.]

As for the F&SF book, Cotts’s problem is, first, that the book includes a number of stories that are basically fairy tales. (True, I suppose, but hardly worth complaining about – this has always been part of the fabric of F&SF.) More seriously, Cotts is bothered by the choice of work by such well-known mainstream writers as Ogden Nash, John Masefield, Howard Fast, Graham Green, Oliver LaFarge, and Horace Walpole.

Cotts is unhappy, I deduce, with a certain appearance of slavish name-dropping by these inclusions, particularly as the selections in question are apparently not major pieces; and also Cotts is annoyed that these stories are none of them original to F&SF, but rather older stories that the magazine reprinted. The final line of the review reads: “Maybe the magazine is too young to comprehend that trying to appear bigger than you are makes you come out smaller in the end.”

An interesting review, and I’d say, not too far off base. Cotts closes with a positive bit on Fred Pohl’s Drunkard’s Walk, noting only that it is not the satire that Pohl had perhaps been typecast as a producer of.

The stories, then:

“A Dusk of Idols,” by James Blish (9,300 words)

“The Unknown,” by William F. Temple (8,400 words)

“The Risk Profession,” by Donald E. Westlake (10,500 words)

“Playboy and the Slime God,” by Isaac Asimov (4,800 words)

“The Last Evolution,” by John W. Campbell, Jr. (7,400 words)

“Political Machine,” by John Jakes (8,200 words)

(A bunch of fairly long stories – many magazines would have listed 5 of the 6 as novelettes, but only the first three above are so listed here.)

(A bunch of fairly long stories – many magazines would have listed 5 of the 6 as novelettes, but only the first three above are so listed here.)

Blish’s “A Dusk of Idols” is set in Blish’s oft-used, but very loosely worked out, future called sometimes “The Haertel Scholium.” More to the immediate point, the story references the “Heart Stars,” an ancient civilization based in the “Heart Stars” of the Galaxy. Humans have applied for entry, and only have 45,000 years or so of probation to go before they can be full members.

Some of this background is mentioned in his two closely-linked, and quite awful, YA novels, The Star Dwellers and Mission to the Heart Stars.

In this story, a wealthy celebrity doctor suddenly gets a conscience and decides to try to help the oppressed citizens of Chandala, who are denied basic sanitation as well as medical treatment by the rulers. His attempts are met as blasphemy and he is chased through a huge sewer, realizing eventually that this state of affairs is purposeful – for essentially eugenic reasons (the lower classes, you see, those who are denied medical treatment, are obviously less fit, and only those that can survive those conditions should reproduce).

The more chilling realization is that Chandala’s social setup is implicitly endorsed by the supposedly uber-civilized Heart Stars – more chilling still is the idea that this is just a more clear expression of the universal state of being. So – it’s a story engaging in interesting and controversial ideas.

Unfortunately, the story itself isn’t quite good enough to sustain its burden. (Or, perhaps, it is either 3,000 words too long or 5,000 words too short.)

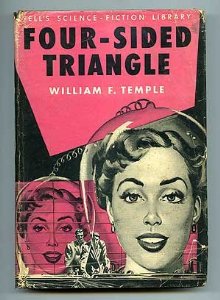

William F. Temple is perhaps the least-known of the writers in this issue, which is odd, as he’s hardly little-known – a close friend (and roommate) of Arthur C. Clarke, and writer of the novel Four Sided Triangle which became an early Hammer film.

“The Unknown” is set in Maine. The main character is a bitter, crippled war veteran, living with his blind former subordinate. They witness a mysterious crash in the woods, and along with a couple more somewhat emotionally broken neighbors, investigate, and find an alien spaceship with an occupant. Their first fear is invasion, and the protagonist’s panic dooms the alien (who to be fair was probably doomed anyway), but the creature shows its basically good nature in the end anyway… Not a bad story, not a great one.

Donald Westlake, of course, became a very famous crime writer, under his own name and his most popular pseudonym, Richard Stark. But early in his career he wrote a lot of SF, before breaking with the field, and more explicitly, John Campbell, in an essay in the fanzine Xero.

Donald Westlake, of course, became a very famous crime writer, under his own name and his most popular pseudonym, Richard Stark. But early in his career he wrote a lot of SF, before breaking with the field, and more explicitly, John Campbell, in an essay in the fanzine Xero.

Westlake was never as good an SF writer as he was a crime writer. (Though who can say what he might have done later in his career had he stuck with SF. He did write a couple of SF/F novels later on.) “The Risk Profession” is probably my favorite Westlake SF story of those I’ve read, and likely it’s not a coincidence that it’s a crime story. Ged Stanton is a fraud investigator for an insurance company. He’s sent out to the asteroids to find a way the company can avoid paying a “retirement plan” to a asteroid prospector. The plans are issued with the intent that most of the plan members will die too soon to collect.

Stanton ends up on the rock where the claimant’s partner is preparing to stake a big claim – it seems the two of them hit it big, but the one man died in an accident before he could collect his money – but not before he could ask for a refund of his Retirement Plan, figuring he wouldn’t need it any more. Obviously, something is fishy – and Stanton indeed figures it out (hey, I figured it out too, from the start) – but there are some neat tricks in the whole setup, and a nice closing twist.

Asimov’s “Playboy and the Slime God,” we are told in a brief editorial introduction, was written in response to a Playboy article that bemoaned the prurient attitude of current day SF (as of 1960, that is) while pointing out, based on Planet Stories-type covers, that SF used to be full of sex.

The story depicts aliens who reproduce by budding encountering humans. One of them worries that Earth-style sexual reproduction will result in humans soon out-competing them (because of faster adaptation). The aliens kidnap a fairly ordinary man and woman and try to make them demonstrate sex, but the two refuse… finally the captain, convinced that his underling’s claim that humans reproduce sexually is nonsense, orders the humans returned, and the aliens leave, after which…

Anyway, Asimov retitled the story “What is This Thing Called Love?” in later collections. He also credited Cele Goldsmith with helping improve the story’s ending considerably.

Anyway, Asimov retitled the story “What is This Thing Called Love?” in later collections. He also credited Cele Goldsmith with helping improve the story’s ending considerably.

Campbell’s “The Last Evolution” is a Classic Reprint, from the August 1932 Amazing. Sam Moskowitz introduces the story, and says that it was written as a replacement for “Twilight” (later published in Astounding as by Don A. Stuart, and regarded as a classic), which had been rejected at Amazing as too moody.

Moskowitz suggests that “The Last Evolution” could also be considered a “Don A. Stuart”-type story. Well, maybe, in theme – it’s about a robot, and how robots succeeded humans, and this particular model robot is being succeeded by better models. But it’s an awful story, static, boring, contrived. Best forgotten, in my view.

Finally, there is a story by another writer who began his career writing a lot of SF, and eventually gained bestsellerdom in another genre, historical fiction is this case – John Jakes. “Political Machine” is fitfully amusing satire about, as the title says, a political machine – a robot that serves as a sort of “Senator,” helping maintain the actual “political machine” (a computer) that truly runs the U.S. The robot is controlled by one political party, and it seems to be in danger of losing the next election to an improved model the other party has introduced.

Much satirical business is made of the competing corrupt parties, and the helpless robot… As I said, fitfully amusing but ultimately not really about much.

Rich Horton’s last retro-review for us was the January 1962 issue of Amazing Stories.

[…] Rich Horton’s last retro-review for us was the March 1961 issue of Amazing Stories. […]