Sean T. M. Stiennon reviews The Black Opera

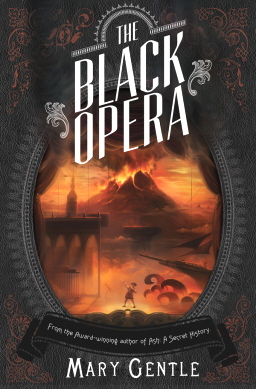

The Black Opera

The Black Opera

By Mary Gentle

Night Shade Books ($15.99, trade paperback, 531 pages, May 2012)

I bought a copy of The Black Opera based on the sheer strength of its premise. A fat fantasy novel set in the baroque world of opera, centered around a production engineered to call Satan himself up from Hell? Sign me up for a first class ticket. If there’s anything that Andrew Lloyd Weber has taught us, it’s that opera is the perfect setting for burning passion, dark secrets, and adventure in the shadows. Adding a diabolical scheme into the mix seems like a perfect way to roll the awesome dial up past 11.

However, the first thing I noticed about The Black Opera is that it wasn’t anything close to the lurid, swash-buckling, cult-fighting novel I wanted. It is, in fact, a rather restrained and stately affair, more concerned with the enlightened intellectual climate of the early 19th century than with blood, romance, and action.

Our hero is Conrad Scalese, an opera librettist living in Naples in the third decade of the 18th century. His first great success, a heretical opera entitled Il Terrore di Parigi, has earned him the malicious regard of the iron-handed Inquisition. Only the intervention of the King Ferdinand saves him from imprisonment, but in return for the king’s protection, Conrad must accept a difficult task.

Ferdinand has learned of the existence of an occult society which believes in two gods: An absent creator, and a more personal god, who they know as the Prince of this World (and whom others might call Lucifer). They believe that the Prince is dormant, and that some catastrophic event is necessary to awaken him and usher in a new golden age — in a word, to return god to a godless, forsaken world. The way they intend to do this is by staging an opera so awesome, it will make Mt. Vesuvius and Mt. Aetna erupt, thus killing thousands in Naples and Sicily as a kind of human sacrifice to the Prince.

Music has power in the world of The Black Opera: The Church is capable of performing Sung Masses which bring about miraculous healings, exorcisms, and other supernatural events. However, the idea of using secular music to create other supernatural effects seems to be a new one devised by this society, known as the Prince’s Men.

Which leads into my first major complaint: the handful of fantastic elements in this novel feel rather fetal, their ramifications not fully considered. If musical performances are capable of sparking such tremendous events as volcanic eruptions, why hasn’t anyone previously discovered this, possibly in the century of operatic performances before the 1820s? The power of opera is supposed to be linked to the emotional reaction of the audience and the Prince’s Men need an appreciative audience to work their sorcery… but what science directs that emotional reaction? It doesn’t seem to be anything in particular about the opera’s content. The idea of an opera so horrifying and blasphemous that its arias can call up Lucifer is a powerful one, but it’s missing from this book. When the libretto of the Black Opera is discovered late in the novel, its plot is a relatively conventional melodrama, remarkable only for the sublime music written for it.

Conrad is tasked to work on a “counter opera,” a performance set to coincide with that of the Black Opera and nullify its cataclysmic effects, but this opera ends up being even less extraordinary: a tale of love triangles and divided loyalties that is fairly standard material for opera. What about this particular piece will parry the Black Opera’s horrific effects? None of the characters seem to know and speculation is limited to a line or two of dialogue.

The Black Opera has its best moments when it chronicles the creative process itself. Conrad has to pore through a stack of books for inspiration, do some hasty research on the Aztec Empire for his setting, and then boil it all down to a full libretto with less than six weeks in which to work, balancing the demands of preening divas with the good of the work as a whole. His opposite number — the opera’s composer — is a preening noble, dubbed “Il Superbo”, whose mix of haughty superiority and bone-dry humor is actually pretty endearing, and his sparring with Conrad is quite entertaining.

Overall, though, The Black Opera has little conflict — certainly not enough conflict to drive a novel that spans five hundred pages in trade paper. Early on, there are ominous indications that the Prince’s Men will be relying on murder and wanton destruction to sabotage the counter-opera, but this threat materializes in a scant handful of incidents that are quickly forgotten by both characters and narrative. Little besides mundane deadline pressures impedes the production of the counter-opera. There are a few squabbles among singers, but the cast here is actually surprisingly polite and accommodating to each other. Personal conflict is mainly provided by a love triangle between Conrad, Il Superbo, and the nobleman’s wife, who once lived with Conrad as his lover.

There’s also a totally extraneous subplot about freeing Napolean from his island exile — resolved in about thirty pages, with no impact on the main plot — some verbal clashes between Conrad and the ghost of his wanton father, and a peripheral love triangle which is resolved by one party throwing up his hands and quitting. In general, though, The Black Opera is a novel about nice, understanding people being accommodating to each other. Even King Fredrick is kind of a marshmallow, proving surprisingly patient when personal squabbles between Conrad and Il Superbo threaten to, ahem, bring about the destruction of his entire kingdom.

The other possibility for dramatic conflict was the clash between Conrad’s loud atheism, the faith of the Church, and the more esoteric beliefs of the Prince’s Men, but, well… not much comes of it. The Church has practically no role in the unfolding of events after an opening scene with the Inquisition knocking on Conrad’s door and Conrad gets one obligatory scene to ramble off a few half-baked atheistic arguments culled more from Dawkins than any contemporary philsophe. The beliefs of the Prince’s Men are explained in a monologue towards the beginning and then never revisited. As for the final fruit of their scheme to summon the Prince of this World, suffice to say that I found it banal and anticlimactic.

There is a tense climax, set in the midst of a volcanic eruption, with seas churning, ash filling the air, and lava flows beginning to creep across the landscape, along with couple major plot twists, but they come too late to save the novel from overall tedium. I offer it a resounding “Bravo!” for ideas and ambition, but the staging and libretto are too poor to carry this performance

Sean lives on top of a sixty foot granite pillar in the heart of Madison, Wisconsin. Once a month, books are drawn up to the top of the pillar via an ingenious pulley system, and sometimes reviews are thrown back down, scribbled on torn pages and transcribed for Black Gate by understanding relatives. When not reading books by starlight or using them as covering against summer rains, Sean contemplates the profoundest truths of existence and digs for belly button lint.

[…] — as the sub-title has it, “a novel of Opera, Volcanoes, and the Mind of God.” Others, ably represented at Black Gate by Sean Stiennon’s review, found the pacing was slack, the fantastic elements underdeveloped — particularly with regard to […]