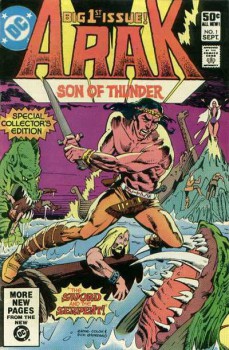

ARAK Issue 1: The Sword and the Serpent!

In the summer of 1981, DC Comics proudly presented “the coming of a great new hero who stalks the fear-haunted shadows of an age of darkness” — Arak, Son of Thunder!

In the summer of 1981, DC Comics proudly presented “the coming of a great new hero who stalks the fear-haunted shadows of an age of darkness” — Arak, Son of Thunder!

Arak was brought to life by Roy Thomas, who’d cut his sword-and-sorcery eyeteeth launching the most successful S&S comic-book franchise ever over at Marvel (the line of Conan titles), and penciler Ernie Colon. It had all the earmarks of such titles — swashbuckling action, magic, monsters, and mayhem — but Arak was not just another generic brute barbarian among the sundry pale imitations of Robert E. Howard’s iconic character. No, Thomas seems to have had bigger ambitions for this epic tale, both in its historical moorings and its complexity.

Thomas uses the back page, the one later reserved for a letters column, to explain what he was up to, in an editorial entitled “A SHORT HISTORY OF THE WORLD, DC-STYLE!”

The editorial begins with the observation “They called them the DARK AGES — but we hope to make them blaze with the light of adventure and heroism.”

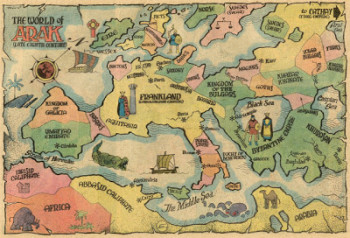

What follows that intriguing lead line is a brief history lesson of the “latter half of the first millennium A.D.,” during which this series is set. Of course, Howard himself used a quasi-historical background for his famous barbarian, but the “Hyborian Age” was set so far in the shadowy past that he had a good deal of leeway. By conceiving his story as historical fantasy set in a more recent era, Thomas does create more work for himself, although, granted, there probably weren’t too many medieval historians who would be reading the comic and calling him out (I certainly wouldn’t know if he got some minor detail wrong about the court of the king of the Franks).

Where his leeway lies — and where he really gets to have fun and play — is in the fact that he clearly defines this as alternate history, predicated on this premise: “Ah, but what if there were another earth somewhere — a parallel planet, existing but a heartbeat away from our world yet forever separated from it — an earth on which events and names and geography were much like our own, but with one all-important difference: What if, on that world…MAGIC WORKED?”

And to seal the deal, he adds, “What if, there, unicorns fenced with fiery-breathed dragons, as werewolves prowled about the campfires of traveling warlocks?”

So we know what we can expect. A lot of verisimilitude provided by a historical background, but with the added element that all the monsters and superstitions that many people believed in back then had an actual basis for being believed in, i.e., the demons and curses and witches were just as real and as common as some people naively seemed to think they were.

So we know what we can expect. A lot of verisimilitude provided by a historical background, but with the added element that all the monsters and superstitions that many people believed in back then had an actual basis for being believed in, i.e., the demons and curses and witches were just as real and as common as some people naively seemed to think they were.

Okay, I’m in. I love this kind of deal.

We open with a row of quick-cut panels showing something emerging from the mist on the sea. At first, it appears to be the head of a dragon, but we quickly learn that it is the prow of a Viking ship (don’t worry — if you paid your fifty cents for this “BIG 1st Issue Special Collector’s Edition” to see sea serpents, one will be delivered in just a few more pages. You’ve got to read a bit of back story and get introduced to a lot of characters first, though).

And here I’ll quote the opening text-boxes verbatim, because it will give me a chance to make some observations about Thomas’s overall style:

“The storm blew its last, just before dawn. Even now, mist-laden fogbanks lie heavy on still-seething waters…and somber clouds hide the sun’s morning face. A ship breaks forth into such light as there is…a ship both dragon-prowed…and dragon-proud. Yet it is weariness, not pride, which marks the men aboard this Viking long-ship, on this dark morn of the world, now twelve centuries agone. For none of them thought, last night in the storm’s sharp teeth, to be alive to greet the morrow…no, not even here, so far from any lands or seas they know. They are Norsemen, mostly…daring sons of thick-forested fjords…though at least one among them murmurs a ballad in the guttural Frankish tongue as he goes about his chores.”

Sure, the prose lists a bit toward the turgid and purple side; Thomas’s pulp influences are quite apparent. If you were writing a parody of that pulp style, you’d only have to do a little tweaking to what we have here (and you’d throw in lots of words like “agone”). There were many comics writers attempting to pen in this style back in the day, and for the most part they are virtually unreadable (except when read for campy melodrama). However, Thomas mostly pulls it off. It may be a somewhat dated style, but it is one he can handle, and even achieve some occasional nice dramatic effects. At his best, Thomas sometimes manages to channel Howard, which of course is why he got these gigs.

Another observation about this opening volley of words is that they read like the first lines of a piece of prose fiction; that is, they don’t actually need any accompanying illustration. That’s another thing a modern reader will discover upon visiting (or revisiting) pre-’90s comics: there is a lot more exposition. There are pros and cons to this.

Another observation about this opening volley of words is that they read like the first lines of a piece of prose fiction; that is, they don’t actually need any accompanying illustration. That’s another thing a modern reader will discover upon visiting (or revisiting) pre-’90s comics: there is a lot more exposition. There are pros and cons to this.

Cons: The biggest con is that it can undermine part of a comic-book’s storytelling power; namely, its ability to convey information visually. The worst offenders tended to provide a blow-by-blow description of what the reader could clearly see in the image. I have chuckled at Doc Samson literally declaring “I will now jump onto this plane’s wing!” as he jumps onto the plane’s wing. Thanks for narrating your life out loud, buddy.

Pros: To appreciate the pros to more prose, read a pro like Thomas in this first issue of Arak. There is a lot of exposition, but when the action happens, he refrains for the most part and lets the action speak for itself. He trusts his penciller to deliver that element of the narrative, and when his characters speak, it is not to provide a redundant voice-over to what they are doing; rather, it is to convey real information that adds to the reader’s knowledge. The other advantage is that you can tell a lot of story in a single issue. Based on how far along Thomas brings the story in this first issue, my mind reels to think how much might eventually transpire over the course of 49 more issues. Contrast that to the ‘90s trend of, for example, Image Comics titles that were all flash and full-page spreads of muscle-bound heroes and villains duking it out. You’d “read” what little there was to read as you admired the art and the layout; five minutes later you’d be at the last panel: Be here next month! And you’d be thinking, wow, at this rate, we should have covered a full day of events by sometime next year. (Of course, that was a company founded by defecting artists who figured they could just write the damn things themselves — and let that be a lesson to you, those in comic-dom or Hollywood who think writers are expendable as long as you have enough visual effects.)

So what do we learn in this story-dense first issue? We can intimate that those wayward Vikings have been thrown off-course very near to North America, because they soon spy a small, sinking craft. It turns out to be a canoe in which is a young boy. When they fish him unconscious from the sea, he immediately rouses superstitious suspicion because of his skin “the color of blood” and the strange weapon — the tomahawk — he clutches.

The “red-skinned wolf-cub” immediately raises the ire of the Viking Sigvald the Skull-Splitter by whipping out a knife and cutting the Viking’s good-luck charm from his neck. It is a pendant of a Hammer of Thunor (the Norse god of thunder, also known as Thor), and why this strange boy is immediately so taken by it sets up a bit of a mystery pertaining to his origin (since the comic’s subtitle is “Son of Thunder,” we can guess).

That would be the end of story right there, folks, if Sigvald had his way. But the Frankish Viking Hermold intervenes on the boy’s behalf, claiming him as a slave. Sigvald grudgingly lets it go, while secretly smoldering and vowing vengeance against the devil-boy coughed up by the sea. This sets up a classic arch-nemesis scenario, or so it would seem. There is some recurring tension between Arak and Sigvald, but as you’ll see, it won’t outlast the issue.

Hermold is a kind and decent fellow who teaches the boy the language and trains him to fight with a sword. Even Arak’s name (which at first appears to be a generic barbarian name such as hack writers are always coming up with, something guttural with a good hard-K consonant in there to make it sound really primitive) has a logical origin: the first sword Hermold presents him with belonged to a deceased friend named Erik. The boy mispronounces the name “Ar-ak?” and that name becomes his own.

We get the obligatory panels of Arak growing into a formidable Viking warrior, but one who, in addition to learning swordplay, fashions a special short axe for himself and who also takes to the bow “as a north-born Viking takes to water.”

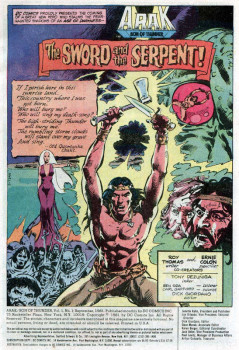

Fast forward eight years, and a Viking raid on a monastery off the coast of Northumbria. We see the bloodthirstiness of Sigvald, now the Jarl or leader of this band, and his men. Here is a typical Thomas flourish to describe the raid: “But it is too late now for either warning or prayer…as from the fierce-prowed longship the invaders pour out onto the rocky beach, like savage Jonahs disgorged from the belly of some obscene whale.” A couple panels later, he notes that the ensuing carnage recalls to mind the text of the abbot’s last sermon: “’Out of the north an evil shall break forth upon all the inhabitants of the land.’ (Jeremiah 1:14)” An incidental observation here: there are only two places in the comic where a piece of text is written in the traditional mix of upper- and lower-case letters: this verse, and an “Old Quontauka Chant” that is reproduced on the opening page: “If I perish here in this sunrise land, This country where I was not born, Who will bury me? Who will sing my death-song? The high-striding Thunder will bury me. The rumbling storm clouds will stand over my grave And sing.” Since Thomas will be drawing on several religions and mythologies over the course of this work, it’s perhaps worth noting that cultural and sacred texts are in some visual way distinguished as they are woven into the framework of the tale.

Arak is now one of the Viking raiders, and freely takes part in the pillaging. However, it is here that we see Arak is not cut of the same cloth. The cruelty shown by some of his comrades turns his stomach, as his ears are filled with “the cries of dying men…of frightened men…of men humiliated beyond all human reason.” He steps in to intervene on behalf of one monk, not out of any particular moral code; indeed, in true anti-hero fashion he tries to rationalize it thus: “How can these monks rebuild their monastery, so that we may plunder them again, if they’re all — *Unhh!*” That logical reasoning is cut short by the Viking Hrolf, who doesn’t want to hear it. However, in deciding to end the conversation and put an end to Arak — “Die then — here among the men in skirts you love so much!” — Hrolf has sealed his own fate. Arak makes short work of him, but then goes back to his uneasy alliance with these bloodthirsty people. His conscience now is pricked, though, and he is also starting to wonder about all these different gods and whether any of them are — or were — real, not least of which is his extinct people’s own thunder god, He-No, whom he was once told was his own father.

As our barbarian hero is troubled by thoughts about the gods of three peoples—the Christian god, the Viking gods, and his own (whom he assumes perished with his people) — winter passes and, soon enough, the dawn of a new season of pillaging arrives.

This time, though, when they return to the monastery they sacked the summer before, they are in for a surprise: a “silver-tressed damsel” with “eyes which seem to glow with a cold inner fire” stands on a rock jutting out of the sea.

Some of the more rational-minded among the raiding party consider this an ill omen, but they are outvoted by the horndogs who declare, “Let’s make the wench our first booty!”

Bad idea, guys. Bad idea. This is Angelica, sorceress from a land called White Cathay, who along with her brother Argalia recently took over the monastery. She summons up a sea serpent (I told you there would be one!), who swiftly sinks the Viking longship. Arak and his old mentor Hermold manage to swim to the rocky shore, as do Svigald and a few of the others.

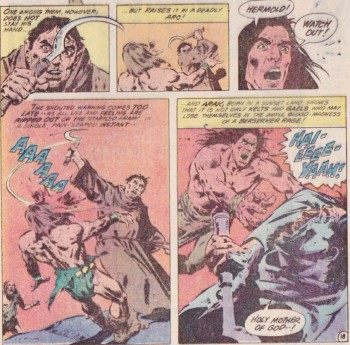

The monks are there to greet them, armed with scythes and pitchforks (an interesting reversal of the virtue of turning swords into plowshares). Some of them want revenge for past raids (understandably, really, because how many times can you turn the other cheek before you have no cheeks left?), with the further motivation that Angelica and her brother have them under their thrall. So they immediately start dispatching the bedraggled, disarmed Vikings. Then one monk does something that he’ll be able to talk over with Saint Peter at the Pearly Gates, because it’s a choice that immediately sends him there: he cuts down kindly (well, as kindly as a Viking can be) old Hermold. Guess what happens next? “And Arak, born in a sunset land, shows that it is not only Kelts and Gaels who may lose themselves in the awful blood-madness of a berserker rage!” The monk’s last words are “HOLY MOTHER OF GOD–!”

The monks are there to greet them, armed with scythes and pitchforks (an interesting reversal of the virtue of turning swords into plowshares). Some of them want revenge for past raids (understandably, really, because how many times can you turn the other cheek before you have no cheeks left?), with the further motivation that Angelica and her brother have them under their thrall. So they immediately start dispatching the bedraggled, disarmed Vikings. Then one monk does something that he’ll be able to talk over with Saint Peter at the Pearly Gates, because it’s a choice that immediately sends him there: he cuts down kindly (well, as kindly as a Viking can be) old Hermold. Guess what happens next? “And Arak, born in a sunset land, shows that it is not only Kelts and Gaels who may lose themselves in the awful blood-madness of a berserker rage!” The monk’s last words are “HOLY MOTHER OF GOD–!”

However, Arak is unarmed and outnumbered, and is soon taken prisoner by the monks. One monk shows him kindness, which turns out to be a very good investment in the “Which one of us is still going to be alive at the end of this comic?” market.

Arak then gets to meet Angelica, who offers to take him on as a personal bodyguard. The only other survivor is Sigvald (got to keep the arch-nemesis, right?), who is kept as a prisoner since he is the Viking leader.

Angelica’s brother Argalia doesn’t trust Arak, and is even less happy when Angelica spills the beans on what they’re up to. They came here to find a magic ring, which Angelica demonstrates — it turns the wearer invisible! The white-haired siblings are now planning on going to the court of Carolus Magnus, King of the Franks, to raise an army. Angelica feels she can trust Arak because he has given an oath not to raise arms against her or her brother — as she observes later, “I could sense you are one who sets great store by oath.” But things aren’t going to go exactly as she plans.

Before she and her brother depart, they plop down Sigvald and the remaining monks on a rock in the sea, and she summons up her serpent to eat these potential witnesses who could blab to others about her magic ring.

Arak, however, having begun to develop some pangs of conscience and a personal code, has a problem with this. He may have just choked the life out of a monk with his bare hands, but that guy had it coming. On the other hand, one of the monks sitting out on that rock waiting to be lunch happened to have been a compassionate fellow, and Arak protests to his new overlady: “I beg you — spare them, witch-woman! They are men of the gods — and one was kind to me!”

No deal. Right about now Angelica is feeling pretty smug that Arak gave his oath not to raise arms against her. Here’s a chance for a fun little plot twist. Arak declares, “Aye, and so I’ll not raise weapons against you or your brother — but only against your pit-spawned monster!”

Which he proceeds to do in a very clever and portentous way. A large, bejeweled cross that Sigvald took in a prior raid had been lashed, upside down, to the mast of their sunken boat because of its resemblance to the storm-hammer of the Viking’s thunder god. Fortuitously, this has washed up on the rock, and Arak grabs it: “Cross of one god — or hammer of another — strike for me now!”

He throws it into the beast’s maw, and at the same time a bolt of lightning strikes from the roiling clouds overhead, vanquishing the serpent. Angelica and her brother have vanished, leaving Arak and the monk he rescued alone to ponder the mysterious ways of God and/or the gods.

Arak’s debut issue closes with him reflecting, “Once, the wise men of my dead tribe told me I was the son of He-No, whose name means thunder. I know not if it was he who saved me this night — to show me he lives, and has followed me across a world — but perhaps I’ll find the answer I seek — at the court of Carolus Magnus, King of the Franks!” The next-issue teaser adds: “And perhaps…the dangerously bewitching Angelica, as well…?”

Oh, and Sigvald the Skull-Splitter, arch-nemesis of Arak: You can cross him off. Just before Arak rescued the kind monk and slew the sea serpent, Sigvald was ignominiously chomped by the serpent. One panel — in the background! — and he’s kaput. Well, there may have been some more dramatic potential in that rivalry, but then again, who’ll really miss him?

Next Issue: “The Savage and the Sorcerer!”

One issue?! This all happened in one issue?! Wow! I don’t think that much happens in a year of most comics these days. 🙂

Thanks for starting this series. You’ve got me interested. Can’t wait to see where it goes next.

Ilene Kaye: “One issue?! This all happened in one issue?! Wow! I don’t think that much happens in a year of most comics these days.”

I know, right? At least in terms of time being entertainingly diverted, you really did get more for your 50 cents back then. 🙂