Reading for the End of the World Redux

Eight years ago, in the wake of the 2016 election, I penned a piece for Black Gate that I called “Reading for the End of the World”, in which I listed a dozen books I thought ideal for helping us get through the four years of turmoil and uncertainty that loomed ahead. I wrote it, posted it, and moved on with my life, little suspecting that coping with that particular cultural earthquake was not a one-time job like getting a vasectomy, but would instead turn out to be an onerous recurring chore like mowing the lawn or doing the laundry.

Well, if He did it again, I suppose I should too. Therefore, once again, “In the spirit of the incipient panic, withered expectations, and rampant paranoia that seem to dominate our current national life, I offer twelve books to get you through the next four years (however long they may actually last): a reading list for the New Normal.” (Groundhog Day is a movie, not a book; that’s why it’s not here.) In 2017 I hoped that the books I discussed would provide some much-needed insight or diversion, and that’s my hope for these twelve additional volumes. Some things have changed after the passage of eight years, however, so now I suppose I should also state that these books were neither written nor selected with the help of A.I. (Of course, that just begs the larger question — how do you know that “Thomas Parker” is a real person? Short answer: you don’t. Then again, I don’t know if any of you are real people, either.)

1. All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren, 1946

Generally considered the greatest American political novel (though Robert Penn Warren denied that he had any explicit political intent in writing it), All the King’s Men follows the rise and fall of Willie Stark, who begins as an idealistic backcountry lawyer and ends as the extraordinarily powerful and ruthless governor of his state. That state is Louisiana, and Willie Stark bears more than a coincidental resemblance to the real-life governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932, Huey Long, who maintained an iron grip on the state even after he left the Baton Rouge statehouse to become a United States Senator and presidential aspirant. Long’s career ended with his assassination in 1935, just as Willie Stark’s life is also cut short by an assassin’s bullet. However, the book is more than just a political roman à clef, more than an incisive portrait of an unscrupulous demagogue or a warning about the dangers such a person can pose for a democracy; fundamentally, it’s meditation on the mysterious conjunctions of character and history, and an examination of the myriad ways personal (and often petty) passions mesh in unforeseen and unpredictable ways, powering the huge, seemingly impersonal processes we all find ourselves caught up in. All the King’s Men (which has been filmed twice, first in 1949, winning Broderick Crawford a Best Actor Oscar for his Category 5 portrayal of Willie Stark, and less successfully in 2006, this time with Sean Penn in the lead role) is a book which will always have something to say to those who want to gain some measure of understanding (if not tranquility) by taking a step back and viewing the storm from a distance.

2. Stayin’ Alive: The 1970’s and the Last Days of the Working Class by Jefferson Cowie, 2010

Stayin’ Alive (the irony of the title becomes increasingly apparent through the course of the book) sheds a bright light on our current condition by chronicling how “The social and political spaces for the collective concerns of working people — the majority of the citizenry — disappeared from American civic life when the nation moved from manufacturing to finance, from troubled hope to jaded ennui, from the compromises and constraints of industrial pluralism to the jungle of the marketplace.” The progression of the key players — labor leaders like Jimmy Hoffa and George Meany and politicians like Hubert Humphrey, Robert and Edward Kennedy, Richard Nixon, George McGovern, George Wallace, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan — illustrates the shift from a working class that defined itself by its material conditions (wages, benefits, working conditions, freedom to unionize) to one that defined itself by positions on so-called “cultural” issues (busing, abortion, “patriotism” loosely defined.) Cowie also has time to look at television, movies and music, from Bruce Springsteen’s album Born to Run, with its message that working class life can’t be transformed but only escaped, to the film Dog Day Afternoon, which says that even escape is impossible. The book’s analysis is brilliant and persuasive, and though Cowie tries to hold out some hope for the future, the picture painted is a bleak one, depicting as it does a landscape of diminished economic opportunity, truncated rights, and withered hope — pretty much the world we live in today, which is a direct result of the 70’s, a decade by the end of which “working people would possess less place and meaningful identity within civic life than at any time since the industrial revolution.”

3.Singular Travels, Campaigns and Adventures of Baron Munchausen by R.E. Raspe and Others, 1948

3.Singular Travels, Campaigns and Adventures of Baron Munchausen by R.E. Raspe and Others, 1948

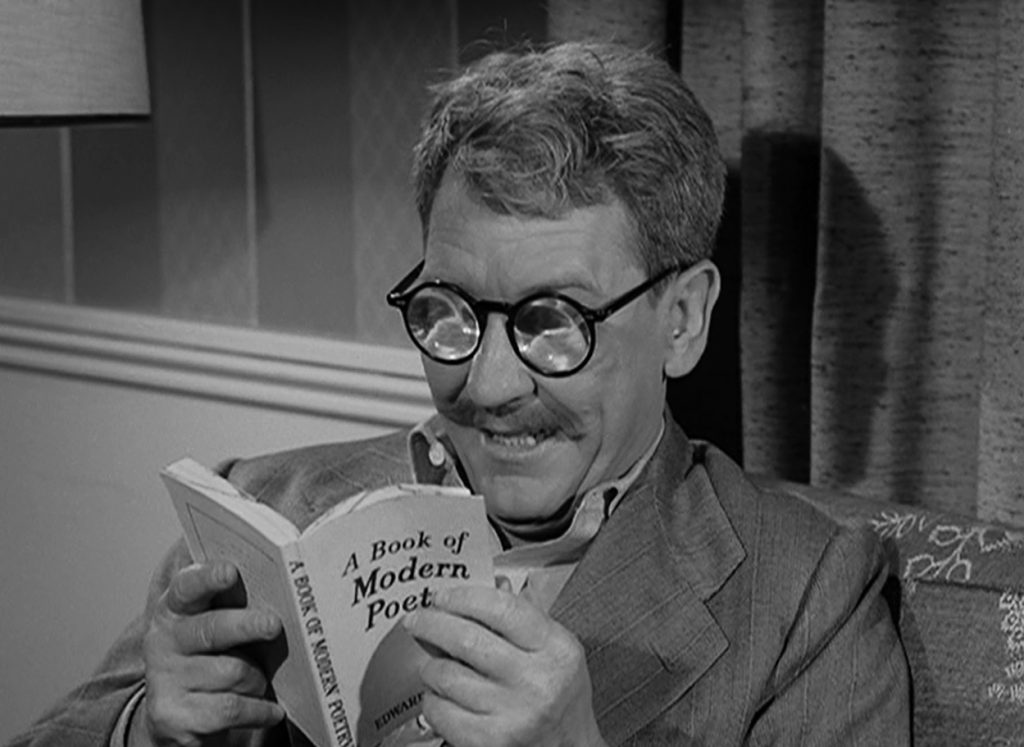

Think carefully before you answer — who is the greatest liar in history? You’re right, of course — it’s Baron Munchausen! In the picaresque novel by Rudolph Erich Raspe, first published in 1785, the nobleman is a nonstop raconteur, spinning stories of his adventures and exploits as a military man and world traveler. Such memoirs were fairly common in the eighteenth century, but few ex-soldiers ever (successfully!) wrestled a forty-foot crocodile, visited the moon by climbing up a beanstalk, rode a flying cannonball over enemy lines, or got swallowed by a great fish while bathing in the Mediterranean (Munchausen freed himself by dancing the hornpipe in the creature’s stomach, which caused it to thrash about and head for the surface, thus attracting the attention of a ship, which harpooned it, hauled it on board, and began cutting it up. “As soon as I perceived a glimmering of light I called out lustily to be released from a situation in which I was now almost suffocated. It is impossible for me to do justice to the degree and kind of astonishment which sat upon every countenance at hearing a human voice issue from a fish, but more so at seeing a naked man walk upright out of his body: in short, gentlemen, I told them the whole story, as I have told you, whilst amazement struck them dumb.”) The actual Baron Munchausen, who fought for Russia in various campaigns against the Turks, spent his retirement entertaining people by telling tall tales about his exploits. Raspe heard some of these yarns and put them into his book along with other outrageous lies of his own invention, which infuriated and humiliated the real Baron, who was driven into seclusion by the ridicule of all Europe. To think that sheer embarrassment could make someone retire from public life; 1785 was a long time ago, was it not? (If you want to read these wildly entertaining adventures, make sure you get an edition that has the original illustrations by Gustave Doré; they are just as funny and delightful as the Baron’s fabulations.)

4. The Iron Dream by Norman Spinrad, 1972

Alternate-history stories come in many varieties, from The Man in the High Castle to Bring the Jubilee to Pavane to Harry Turtledove’s infinitely expanding oeuvre, but few of them are as audacious and original as Norman Spinrad’s foray into the genre, The Iron Dream. The inside-cover blurb lets you know what you’re in for: “Let Adolf Hitler transport you to a far-future Earth, where only FEREC JAGGAR and his mighty weapon, the Steel Commander, stand between the remnants of true humanity and annihilation at the hands of the totally evil Dominators and the mindless mutant hordes they completely control.” That pretty much sums up the plot of the novel (which, once you get past the book’s cover, actually turns out to be titled Lord of the Swastika), and the alternate-history aspect is taken care of by an “About the Author” note at the beginning of the book and an “Afterword to the Second Edition” at the end, purportedly written in 1959 by a New York University academic named Homer Whipple. The bio tells us that after serving in the Great War and briefly dabbling in “radical politics”, Adolf Hitler emigrated to New York in 1919, where he first became a successful science fiction illustrator (for Amazing, no less) and then a science fiction writer himself, the author of such classics as Savior from Space, The Thousand Year Rule, The Master Race, and Tomorrow the World. In the afterword, Whipple chronicles Hitler’s literary career up until his death in 1953, afterwards analyzing Lord of the Swastika and finding in its fetishistic imagery the source of the book’s lasting appeal to hardcore science fiction fans, who awarded Hitler a posthumous Hugo in 1954… so what we have here is not a novel about an alternate history — it’s a novel from an alternate history. How is Lord of the Swastika? (Spinrad reportedly wanted the book to be published under that title, with only Hitler’s name on the cover, but was stymied by his publisher.) Well, based on my own reading about Der Führer (primarily the Bullock and Kershaw biographies, Speer’s memoirs, and Richard Evans’ history of the Third Reich), Spinrad is disquietingly successful at transmogrifying Hitler’s pathological obsessions and rigid, paranoid worldview into pulp science fiction, and one of the most remarkable things about the book is its uncomfortably pointed demonstration of how perfectly the themes and devices of pulp sf suit a violent, authoritarian imagination. In any case, being locked up inside Adolf’s head, even for satirical purposes, isn’t all that enjoyable, and well before the book ends, distaste begins to outweigh novelty, and you’re eager for the “author” to… well, blow his brains out. Spinrad may have been just a little too clever, and The Iron Dream might be one of those books that would be twice as effective at half the length. Still, it’s quite a ride, and I can’t think of another novel like it.

5. Spider Kiss by Harlan Ellison, 1961

Harlan Ellison was one of our best short story writers, but he produced only a few genuine novels. Among that handful, though, is one of his best works, his rock-and-roll novel Spider Kiss (which was originally published by Gold Medal — the mark of quality! — as Rockabilly). Country boy Luther Sellars has an abundance of musical ability and a limitless desire to push, claw, and gouge his way to the top, a vicious, elemental drive unmediated by any trace of scruple. After changing his name to Stag Preston, he succeeds in climbing to the pinnacle of pop music success, becoming the idol of millions. Stag’s unholy combination of ferocious ambition, demonic talent, and unbridled appetite (especially his sexual one) finally lead to his downfall, and after his scandalous excesses (which include some genuine and serious crimes) send him careening to the bottom, he ends his days playing is a sleazy strip joint, far from the big money and the bright lights, mercifully forgotten. Ellison clearly knew the great 1957 Elia Kazan film A Face in the Crowd, in which Andy Griffith excels as Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes, a folksy entertainer whose good old boy demeanor conceals a very nasty streak and who plays out a rise-and-fall story very similar to Stag’s. Stag is, if anything, even worse than Rhodes, and the book is a riveting portrait of a driven and near-sociopathic personality. Ellison later retrofitted many elements of Stag’s character and story onto his script for the 1966 film The Oscar (in which the amoral user is an actor named Frank Fane), a movie so godawful it’s divine.

6. 85 Days: The Last Campaign of Robert Kennedy by Jules Whitcover, 1969

We’ve gotten used to some wild presidential elections over the last decade and a half, but few campaigns in American history were as chaotic, divisive, and ultimately tragic as the one all the way back in 1968. When President Lyndon Johnson announced that he was not going to run for re-election, Robert Kennedy at first publicly said that he wasn’t going to seek the nomination himself, a decision that went against all of his political instincts. It galled him to leave the field to Hubert Humphrey (Johnson’s vice-president and a man likely to continue LBJ’s war policies) and the upstart anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy, but when McCarthy’s surprising early success showed the potential strength of an anti-Vietnam War candidate, Kennedy threw his hat into the ring. A frantic campaign followed, with RFK scrambling to put together an organization, enter primaries, and make up an enormous amount of lost ground. Along the way, Kennedy earned the animus of McCarthy (for stealing his thunder — and his young, anti-war voters) and Johnson (for opposing his policies), made Kennedy history by losing one primary (Oregon), gained some momentum by winning others (South Dakota, Nebraska), and was called on to help the country weather the shock of the Martin Luther King jr. assassination, a bare eight weeks before his own death at the hands of Sirhan Sirhan on the night he won his greatest victory in California — all in eighty-five days (three weeks less than Vice President Harris had in her own truncated campaign). Whitcover’s book is a definitive account of one of the most dramatic political contests in our history, a kind of combat-photographer snapshot taken at a moment when the country seemed hurtling toward the apocalypse — and not for the last time.

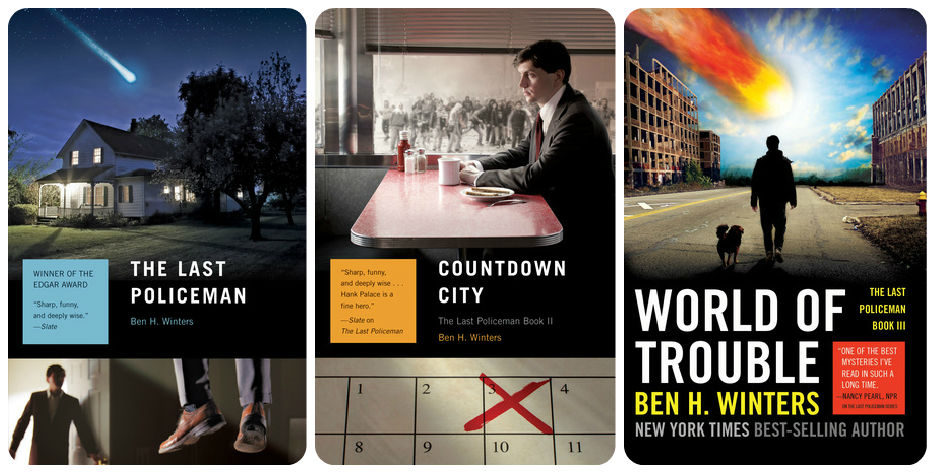

7. The Last Policeman Trilogy (The Last Policeman, Countdown City, World of Trouble) by Ben H. Winters, 2012-2014

If you think things are bad now, take heart — they could be worse. The world could be ending literally rather than metaphorically; there could be a ginormous asteroid on a collision course with earth that will extinguish human civilization on impact, which is the situation faced by Hank Palace at the beginning of The Last Policeman trilogy. The first volume, The Last Policeman, begins with the asteroid (named “Maia”) still six months away and the chances of impact rising but still less than one hundred percent. Before the end of the book, doom has become a mathematical certainty and Palace and everyone else on earth are faced with the Big Question — what do you do when everything is coming to an end? You keep doing your job, of course; it’s that or go crazy in one of a thousand different ways. There’s no shortage of people going that route, but Palace chooses the first option; despite knowing how ultimately futile his efforts are, he continues to get up every morning and show up for work as a Concord, New Hampshire police detective, spending his dwindling stock of days trying to keep his small part of the world from falling to pieces. Through the course of the three books, Palace investigates murders (in a world where the innocent and the guilty alike are about to experience maximum punishment) and a strange disappearance (in a world where increasing numbers of people are walking away from the rubble that’s all that’s left of pre-Maia society) and most personally, trying to find his troubled sister Nico, who has vanished into the chaos; he has some things to settle with her before the end. What does any of it matter? Well, Winters has said the theme of the trilogy is, “Why does anybody do anything?” Each volume (almost each chapter in each volume, in fact) is more involving than the one that preceded it (increasing tension is built into the premise) and aside from being a gripping read, the series really does prompt reflection on the meaning of human actions when the actors are faced with unavoidable death — which we all are, asteroid or no asteroid.

8. 1876 by Gore Vidal, 1976

Electoral chicanery is as old as the republic itself, and who better to describe perhaps the greatest example of it in our history than Gore Vidal, America’s premier historical novelist? In this, the third novel in his six-volume Narratives of Empire series (following Burr and Lincoln in internal chronology), Vidal fictionalizes the centennial election of 1876, when the presidency was stolen from the Democratic candidate Samuel Tilden (remember him? Of course you don’t!) by the Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, or at least by his faction. Post-Civil War bitterness (the tactic of “waving the bloody shirt” to brand all Democrats as crypto-Confederate traitors reached new heights during the contest) led to outrageous underhandedness and outright fraud across multiple states. In South Carolina, for example, 101 percent of all eligible voters voted (take that, electoral apathy!) and many of the things that we’ve become drearily familiar with reared their ugly heads, such as disputed electors, confusing or deceptive ballot designs, and rancorous squabbles about the counting and certifying of electoral votes. With Inauguration Day approaching and the results a snarl beyond untangling, Congress headed off increasing financial and political chaos (to say nothing of threats of violence — Hayes’ home was shot at shortly after Election Day) by creating a special bipartisan electoral commission to reach some kind of resolution, with the result that the Republican candidate became the nineteenth President of the United States… by one electoral vote. (Tilden’s consolation prize was winning the popular vote; I’m sure that kept him warm at night.) All of Vidal’s virtues are on display here; no one depicted drawing-room politics (or any other kind, for that matter) with more elegant irony or acerbic wit. This Jamesian comedy of manners has the kind of effortless style that makes it easy to miss the cold-steel scalpel in the author’s hand, and he uses the knife to mercilessly dissect the corruptions and hypocrisies of Hayes’ and Tilden’s time, and, by implication, our own.

9. The Autumn of the Patriarch by Gabriel García Márquez, 1975

In The Autumn of the Patriarch Gabriel García Márquez uses the techniques of magical realism that he employed in One Hundred Years of Solitude to portray the life and (maybe) death of the archetypal figure of a military tyrant or Caudillo, embodied in a nameless Caribbean dictator. Instead of using the tools of objective realism to depict the surface of his dictator’s reign, García Márquez employs symbol, metaphor and dream to place us in the lightless mind of his radically isolated protagonist. The book (the English translation is by Gregory Rabassa, who also did the magnificent translation of One Hundred Years of Solitude) is not for the faint of heart — it has one sentence that’s fifty pages long. Most of the novel consists of a stream of consciousness that runs so deep you can easily drown in it, but the method yields dividends that couldn’t have been gained in any other way; in one extraordinary, hallucinatory scene, in his greed and callousness the monomaniacal “General of the Universe” (his official title) sells off the Caribbean Sea to the Americans who keep his regime propped up; the Gringos send helicopters to fly off huge sections of the Sea, which has been cut up into numbered squares, leaving only a desiccated, sea-bottom desert behind. The book exuberantly chronicles the General’s flagrant excesses — political, military, familial, financial, rhetorical, sexual — but García Márquez’s greatest triumph is that his art moves us beyond mere externals, imprisoning us in the free-floating abattoir that must have been the mind of a Somoza, a Stalin, a Franco, a Mao.

10. Advise and Consent by Allen Drury, 1959

Though the current confirmation battles roiling the Hallowed Halls of the Capitol may seem especially contentious and nasty, the process of getting even a mildly questionable nominee through the Senate has always been a bloodsport. If you doubt that, just read Allen Drury’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Advise and Consent. (The title comes from Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution, which gives the President the power to appoint various federal officers and officials with the “Advice and Consent of the Senate.”) When liberal golden boy Robert Leffingwell is nominated by the president for Secretary of State, the confirmation process is expected to go smoothly, and it does — until a witness surfaces with evidence that Leffingwell had once been a communist (a charge that the nominee has unequivocally denied under oath). Those in favor of Leffingwell (a group that still includes the president) and those opposed to him begin to frantically maneuver for advantage, working night and day to discredit whatever evidence and witnesses are presented by the other side. Before the drama’s end, the president himself will be involved in blackmailing Utah Senator Brig Anderson, who has proof that Leffingwell’s testimony was a lie. Anderson had a homosexual encounter in his past, and the prospect of that incident becoming public knowledge drives him to commit suicide in his Senate office (a plausible outcome in 1959 — and something very much like it had actually happened in 1954). In the wake of this tragedy, the evidence against Leffingwell gets out, along with the president’s role in its suppression, with the result that the nomination goes down to a decisive defeat. Allen Drury (whom Richard Nixon believed to be secretly gay himself) was a seasoned Washington reporter who knew all the back-room details of how the sausage was made, and after over sixty years, Advise and Consent still deserves its reputation as one of the greatest of American political novels. Drury must have agreed — he wrote five more books carrying the story and characters forward into a shrewdly speculative political future. Otto Preminger directed an excellent film version in 1962, with Henry Fonda as the flawed nominee and Charles Laughton (in his final role) as Senator Seab Cooley, Leffingwell’s most intractable opponent.

11. The Loneliest Campaign: The Truman Victory of 1948 by Irwin Ross, 1968

Everyone loves an incredible comeback staged by a tenacious underdog, right? Well, um… maybe not everybody. But if you crave a candidate wielding a pugnacious (and sometimes profane) campaigning style to present himself as a battler for the common man against out-of-touch elites, if you delight in baffling and egregious polling errors, if you yearn to see a complacent national press stunned by an unexpected outcome that they find simply incomprehensible, then have I got a story for you! No, not that one; it’s not necessary to look back just a month or two, because our grandparents (or great-grandparents!) saw it first back in 1948, when Harry Truman, unanimously written off by the media as a comically inept buffoon, came roaring from behind to defeat supposed shoo-in Thomas E. Dewey for the presidency. Truman, the low-class ward-heeler, the Missouri machine politician who was tapped for vice-president when Franklin D. Roosevelt decided to jettison his previous running mate, the increasingly problematic Henry Wallace, became president when FDR died three months into his fourth term. Shackled by foreign policy problems and an unstable economy, Truman (often derided as “His Accidency”) ended his slightly-shortened first term with near-historically low approval ratings. Good thing polls are never wrong. Dewey, brimming with confidence, decided that it wasn’t necessary to win the presidency; he just had to be careful not to lose it. He therefore confined himself to bland, noncommittal statements that were so general as to be essentially meaningless. The Louisville Carrier-Journal mercilessly (but accurately) said that Dewey’s major speeches “can be boiled down to these historic four sentences: Agriculture is important. Our rivers are full of fish. You cannot have freedom without liberty. Our future lies ahead.” Truman, meanwhile, fought his way off the ropes with a no-holds-barred, bare-knuckle exuberance that, fairly or not, laid all of the country’s ills squarely at the feet of Dewey’s Republican Party. When the dust settled, Harry Truman had won one of the unlikeliest second terms in American history, though it’s probably dropped from first place to second in that regard. The Loneliest Campaign is an engaging look at one of the most colorful presidential contests ever, and the book’s conclusion, written in 1968 about the election of 1948, is just as valuable today: “In the end, the most salutary consequence of 1948 was probably a renewed awareness of the contingent quality of events, of the unpredictability of both leadership in a democracy and of the choices that voters make in the privacy of the voting booth. Not for a long time afterward were politicians likely to take the American voter for granted.” We can hope that recent events have provided a much-needed refresher course in that uncomfortable truth.

12. The Road by Cormac McCarthy, 2006

What do you do when nothing is left of all that you and those who went before you have built but charred rubble and blackened ashes? You hold on tightly to the one most precious to you and make your way through whatever lies ahead one day at a time, trying to keep alive a spark of belief that one day, things will get better. In Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic novel, a father and a son (we never learn their names; in this place names are needless encumbrances, relics of a dead past) painfully make their way through a shattered world, looking for somewhere they can rest and find peace, knowing that such a place almost certainly doesn’t exist. We don’t know what happened to the world and neither do they. What does it matter? The only reality is trying to keep their bodies and souls alive in a world implacably inimical to both. Most of the devices of the standard post-apocalyptic story are here, images and incidents that have become familiar (even shopworn) through their use in countless books, movies and television shows: searching for uncontaminated water or a slightly better piece of clothing, picking through dead buildings for canned food, exchanging a word or two with other scarecrow-like wayfarers, the dazed, the dead-eyed, the demented, and hiding from other creatures that were once human but that the universal catastrophe has rendered nothing but feral beasts without mercy or compassion. As they push their shopping-cart (their most precious possession, bearing the few pitiful belongings that are everything they own) through this hellscape, “carrying the fire” (an image for preserving and protecting the human that recurs through much of McCarthy’s work), the vision is almost unendurable in its pitiless extremity — but only almost. It is true that no blows are softened, but we are kept going by two things: the bleached beauty of McCarthy’s extraordinary prose and the desperate love of the father and son, who are, quite literally, all the world to each other. Along the way, we get things no other writer could have given us, like the scene where the pair briefly take refuge in a well-stocked underground bunker that they discover, where the father gives his child a drink, a draught from a world and a life that have vanished forever — Coca-Cola. The father’s delight at his son’s stunned amazement at this drink that seems almost alive, followed immediately by his sadness at knowing that his boy will never taste it again, are emotionally overwhelming, as is the book as a whole. The Road will make you weep; it will make your heart ache unbearably before breaking it in pieces, but this bleak journey ends with the fire still burning; at the end, against all odds, the father has passed the flame on by saving his son, and when you finish this remarkable novel, you will feel that light and heat burning anew in yourself.

Of the twelve books I’ve listed here, only The Loneliest Campaign is currently out of print, but it’s relatively easy to find used on Ebay or from other sources; the other books are all readily available in physical or electronic formats.

So, (again repeating my words of eight years ago), “there you have it: a dozen histories, actual and alternate, maps of action or aids to contemplation, to help you get through all the days of farce and folly that lay ahead, as we do our best to cope with the real history that we’re all trapped in.”

Oh, one more thing — I’m damn sure not doing this again in 2028 (or, God help us, 2032)!

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Say It Ain’t So

Thanks, some great choices, most of which I haven’t read! To your last point, though, my sense is that 2028 (or 2026?), may actually be your last chance to ‘not do this again’…

Right you are, Bill – corrected. Clearly, I’m starting to lose it already…

That’s a fascinating list and sadly more grimly timely than ever. I haven’t read “Stayin’ Alive” but I grew up in a solidly Democratic blue collar family/community in the late sixties and seventies and everything you cite from the book I witnessed first hand. Even as a kid I felt an enormous sense of betrayal by the Democratic party’s pivot to white collar lip service liberalism that effectively turned progressive ideology into a hollow religion.

While I can’t begin to wrap my head around the poor and struggling working class voting Republican (especially THIS Republican party) I can empathize with their anger at neoliberalism’s warped notion of social justice that is oblivious to the basic needs of people in our own communities and contempt for anyone without a college degree.

Thanks for updating this post and I’ll be adding a number of these titles to my reading list.

I wouldn’t claim that I wasn’t surprised in 2016 – or three months ago – but I do think I was somewhat less surprised than many people I know, and I credit that to Stayin’ Alive, which I read in 2013. It changed the way I thought about a lot of things, and there’s no book in this piece (or the one from eight years ago, for that matter) that I’ve recommended to more people.

I read a lot of political writing, fiction (1876, Advise and Consent) and non-fiction (Making of the President series) back in the day, but I totally missed The Loneliest Campaign, even while gushing over Merle Miller’s Plain Speaking (1974), an oral bio of Harry Truman. Thank you for the heads-up, Mr. Parker!

And the apocrypha surrounding The Iron Dream includes Mr. Spinrad getting fan letters asking if and when the sequel to Lord of the Swastika would be published. *shudder*

I like Norman Spinrad’s stories – read The Iron Dream – was like Gamma World playing a Knight of Genetic Purity. If you think that’s awful, try “The Men in the Jungle”. He also wrote a satirical short story in “After the Flames” about a crazed oil shiek trying to get Nuclear weaopons. Lots of other ones like “A World Between” and “A world in Balance” about a quest for Ecotopia and outside forces causing a war of the sexes on an otherwised balanced world.

I’ve never read The Iron Dream, but weirdly, I remember first learning about it from a book review in Dragon Magazine back in the early 80s.

I’ve got The Iron Dream on my shelf, but have never read it. But the reason it is there is I found it at a used bookshop and specifically remembered the cover from that Dragon Magazine article. Weird coincidence!

It occurs to me that The Iron Dream fits into a whole category of books that might be called “Alternate Adolfs.” Beryl Bainbridge’s Young Adolf would be there, and so would George Steiner’s The Portage to San Christobal of A.H. I’ll bet there are a lot of others.