You Will Know—Singularity! Singularity Sky by Charles Stross

There’s a backstory to my reviewing Singularity Sky. Its 2003 publication date made it chronologically eligible for the 2004 Prometheus Award for Best Novel. But it was Stross’s first book publication, and none of the Libertarian Futurist Society’s members happened to read it until that year’s finalists had already been chosen.

However, there was a campaign to write it in, and in fact it received a substantial number of votes, though not quite enough to win; had it been nominated, it might well have won. Now, much later, it’s eligible for the Hall of Fame Award, which can go to works at least twenty years old — and it’s been nominated for that award. As the chair of the committee that chooses Hall of Fame finalists, I’ve just finished rereading it.

[Click images for singular versions.]

|

|

Singularity Sky (Ace Books reprint edition, July 2004). Cover by Danilo Ducak

Singularity Sky seems kind of marginal as libertarian science fiction. Two of the characters, Martin Springfield and Rachel Mansour, say that Earth, their native planet, has an anarchocapitalist legal system (one based on private law enforcement firms competing for customers); early on, Martin tells a police officer,

For legislation and insurance, I use Pinkertons, with a backup strategic infringement policy from the New Model Air Force… For reasons of nostalgia, I am a registered citizen of the People’s Republic of West Yorkshire, although I haven’t been back there for twenty years. But I wouldn’t say I was answerable to any of these, except my contractual partners — and they’re equally answerable to me.

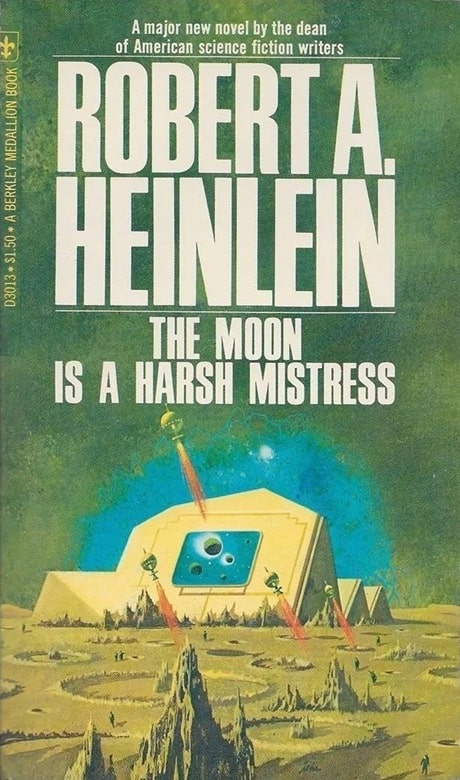

But none of the story takes place on Earth, and there are no scenes showing how things actually work there (as there were, for example, in Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress or Vinge’s “The Ungoverned”). What we get seems to be a bit of surface ornamentation rather than a load-bearing speculative element.

|

|

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert A. Heinlein (Berkley Medallion, September 1968). Cover by Paul Lehr

The actual setting of the story is the New Republic, which, despite its name, seems to be modeled culturally on Tsarist Russia. More precisely, it’s a colony of the New Republic in another solar system, Novy Petrograd, and a New Republican space fleet sent there, with Martin on board as an engineering consultant and Rachel as a diplomatic representative.

We see a great deal about naval operations and naval protocol, and about the New Republic’s security forces and the bureaucratic culture that supports them. It gradually emerges that some time in the past, a cosmic entity from the distant future, the Eschaton, reached back in time and scattered most of Earth’s population across multiple solar systems, where they created new societies largely influenced by historical cultures.

In the course of the novel, the New Republic has to deal with three different versions of liberation that undermine its institutions and customs. First is the Marxist – Gilderist underground on Novy Petrograd (the juxtaposition seems like a hat tip to Ken MacLeod’s early novels), which aims at the overthrow of the established regime through conventional revolutionary politics. Second is Earth, a source of subversive ideas such as “the concept of tax is no different from extortion” that the security forces class as “nonsense verging on sedition.”

|

|

Sequels to Singularity Sky: Iron Sunrise and Accelerando (Ace Books,

July 2005 and July 2006). Covers by Danilo Ducak and Digital Vision

Third, and most powerful, is the Festival, an interstellar fleet of artificial intelligences that goes from star to star opening up communications channels based on quantum entanglement. The Festival’s first step is to bombard Novy Petrograd with telephones, which can be used to speak with it; as a result of these conversations, it grants wishes in exchange for stories and other cultural material. These three intersect in complicated ways in the course of the novel.

One of the important speculative elements in Singularity Sky is the cornucopia machine. The revolutionary leaders have theories about them; in the Prologue they offer to give the Festival a manuscript discussing such a theory in exchange for a cornucopia machine. Rachel Mansour brought a cornucopia seed from Earth, intended to subvert the New Republic’s control of Novy Petrograd. However, the Festival makes her project redundant by flooding the planet with cornucopia machines in trade for folktales and other cultural artifacts. Thus, the concept ties together all three major plot threads.

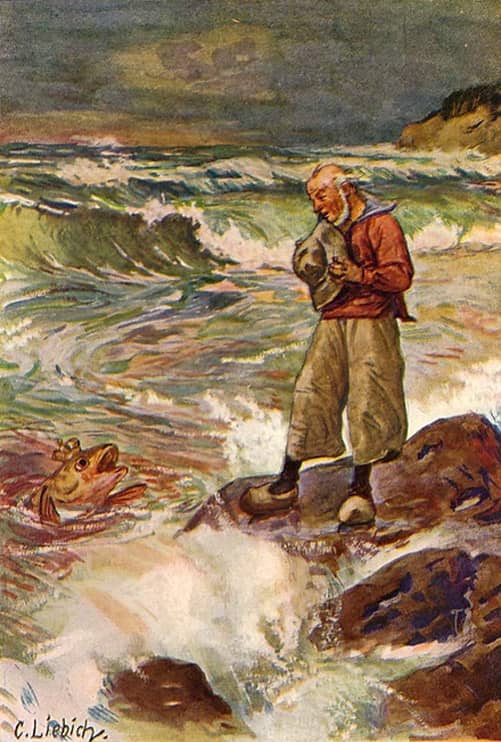

The obvious interpretation of the cornucopia machine is as a basis for a post-scarcity society. But in Stross’s narrative, it’s more like a wish-granting genie or fairy godmother — one that will grant exactly what you wish for, without protecting you against the implications of your wish! The result is that Novy Petrograd turns into a posthuman chaos filled with elements from Russian folklore (for example, an alien who arrived with the Festival travels about in a vehicle remarkably like Baba Yaga’s hut with chicken legs). The whole story thus has the flavor of a fairy tale with a cautionary moral. Indeed it’s a bit like the Brothers Grimm’s story of “The Fisherman and His Wife” in a science fictional setting.

The other major element is an exploration of the implications of superluminal travel. Stross makes a point of the conclusion from relativistic physics that going faster than light is potentially equivalent to time travel; the New Republic’s fleet sets out to exploit this as a basis for naval strategy, by sending an invading fleet back in time to before the Festival is ready for it.

This turns out to be exactly the sort of thing that gets the Eschaton’s attention: not wanting to see anyone change the past to prevent its coming to be, it takes steps when anyone engages in time travel — and Martin is one of its agents. However, a deeper point is Stross’s skepticism about the idea that interstellar navies will also encounter other interstellar navies at the same point of development technologically; Stross has written about the Battle of Tsushima Straits as an example of what can happen when there’s even a modest technological gap between two fleets. The gap between the New Republic and the Festival is far greater. The possibility of time travel also provides an explanation for the presence of the Eschaton.

Putting all this together gives us a book that’s rich in ideas and story elements — maybe just a little too rich; the effect is sometimes confusing. Science fiction is often described as a literature of ideas; like a literary Stakhanovite, Stross seems to be overfulfilling his quota!

On the other hand, it does a very good job of the bombarding-the-reader-with-ideas effect of classic SF writers such as A.E. Van Vogt. I can certainly see why it made a big splash when Stross was starting his career.

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels. His last article for us was a review of St Trinian’s: The Entire Appalling Business by Ronald Searle.

On the cover of the first photo, the UK edition, the blurb by Gardner Dozois is a direct rip off of an exact blurb Isaac Asimov gave to Robert Silverberg that appeared in many places: “Where Silverberg goes today, science fiction will follow tomorrow.” Blatant blurgiarism!