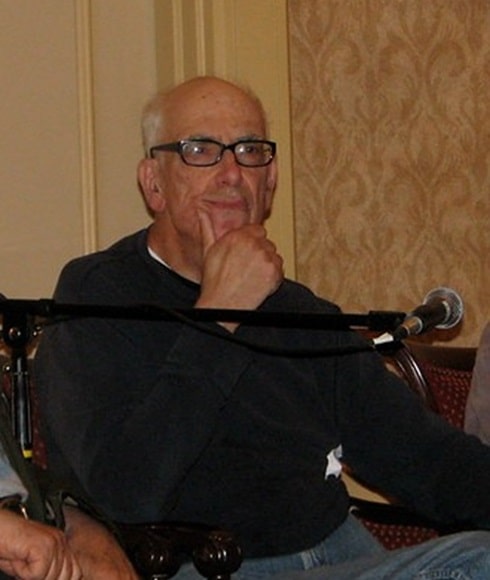

Barry N. Malzberg, July 24, 1939 – December 19, 2024

Barry Malzberg died Thursday, December 19, 2024, at the age of 85. I never met Barry in person, but I knew him through correspondence — much of it on an email list, but also some personal email — for at least a quarter century. But I knew him as an author for far longer. When I was first buying books from the local drugstore, at the age of 14 or so, I bought a great many of his novels, slim paperbacks off the spinner rack. I confess that I bought the first one in part because it was 95 cents, and other books on the rack were $1.25. But I was immediately taken with his voice, one of the most recognizable voices in SF at that time, and I kept buying his books.

Malzberg was born in New York City on July 24, 1939. He was an avid reader of SF throughout the 1950s. He attended Syracuse, graduating in 1960 and returning in 1964 to study creative writing (fellow students included Joyce Carol Oates and Harvey Jacobs.) He received fellowships in creative writing and in playwriting, but had no success selling to literary magazines. He took a job with the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, and began selling stories to men’s magazine and SF magazines, as well as novels in various genres, including erotica.

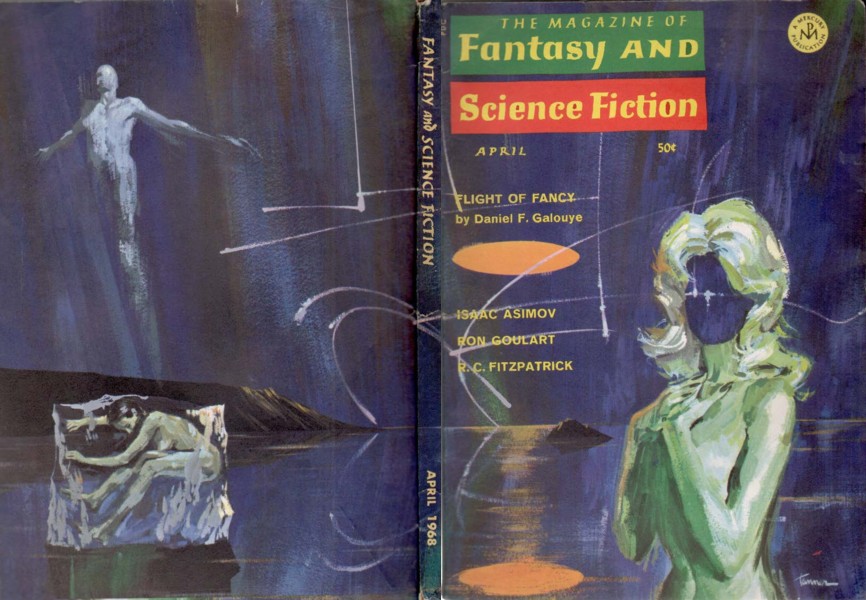

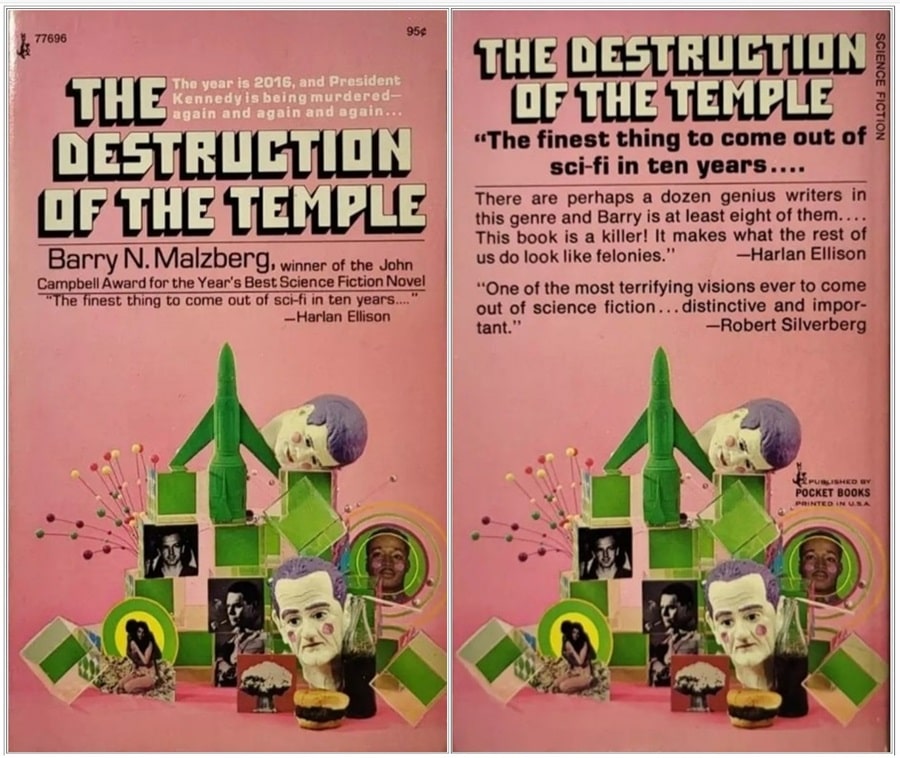

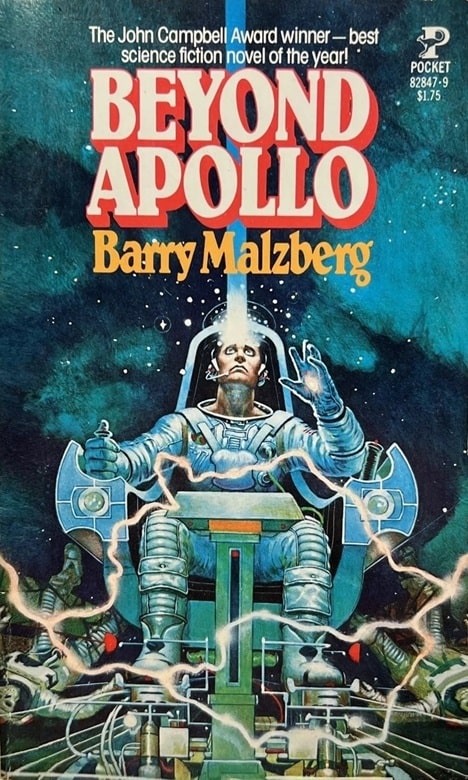

[Click covers for larger versions.]

His early SF was often as by “K. M. McDonnell,” an homage to the great writing team of Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore as well as their pseudonym “Lawrence O’Donnell.” His first SF story appeared in 1967, and his first story to gain wide notice was the brilliant novelette “Final War,” which appeared in F&SF in April 1968 and received a Nebula nomination.

For roughly the next decade he was very prolific in multiple fields, producing in the neighborhood of 100 novels. Most of the best of this work was SF.

Barry was, as I note, a very prolific writer, and at the same time a very ambitious writer. The prolificity sometimes interfered with the ambition, and the weaker novels show signs of padding, and repetition of themes.

But his best work was excellent — novels like The Destruction of the Temple, Beyond Apollo, Herovit’s World, and non-genre work such as Underlay.

|

|

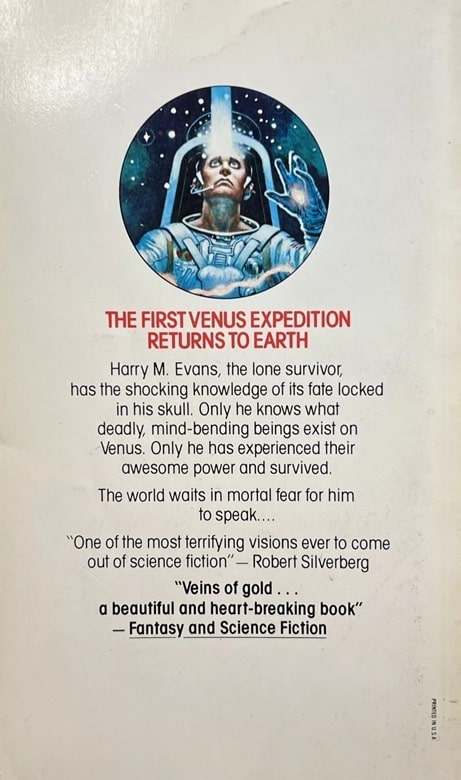

Beyond Apollo (Pocket Books reprint, June 1979). Cover by Don Maitz

Beyond Apollo won the first John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Novel in 1973, and while the award was controversial, as its mordant view of the space program was said to be counter to Campbell’s own vision, it was well-deserved. And the novel showed the way to a generally more realistic examination of both the potential in the space program, and the pitfalls.

He examined the psyche of his protagonists confronting a hostile and difficult to comprehend universe — with problems that can easily be seen as representations of their real-life frustrations — with their marriages and their jobs and the state of life and politics. Many of the protagonists were astronauts, and many more were writers.

|

|

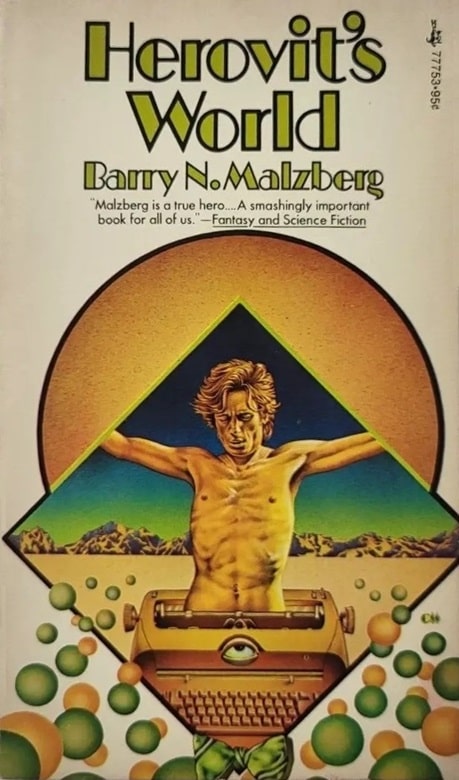

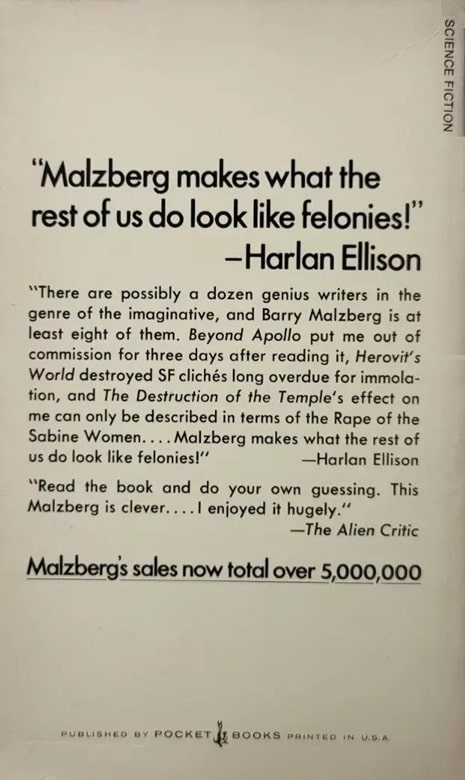

Herovit’s World (Pocket Books, July 1974). Cover by Charles Moll

It’s fair to say that a good subset of his fiction is commentary on the writing life: on the battle between literary ambition and commercial success, and the annoyances of working with philistine publishers, and on the gulf between one’s dreams for one’s writing and the quality of what one produces. The ground he plowed was perhaps narrow, but the crop harvested was lush. Even as many of these novels (and the stories from the same era) are outwardly very pessimistic, they are all also very funny — in a particularly dry and mordant fashion.

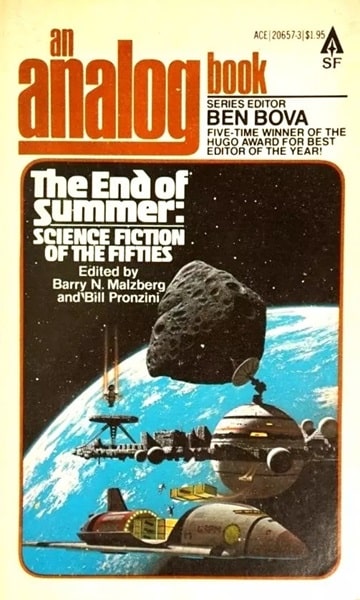

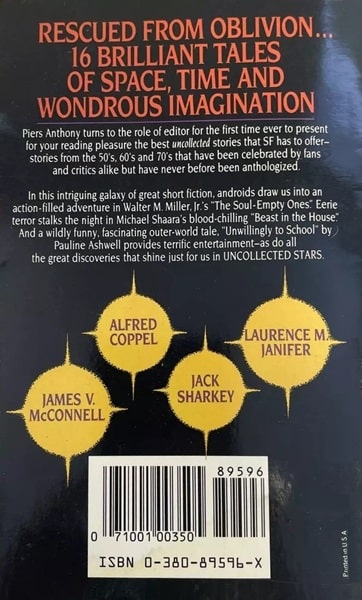

His career as a novelist ended, to all intents and purposes, by the early ’80s, but he kept writing short fiction, much of it in collaboration with the likes of Bill Pronzini and Kathe Koja, up to his death. He also contributed as an editor (briefly) of Amazing Stories, and as an anthologist, of major original anthologies like Final Stage (1974, with Edward L. Ferman) and reprint anthologies, the best, to my antiquarian tastes, being three books with a goal of bringing to wider attention some underappreciated SF stories (many from the ’50s.)

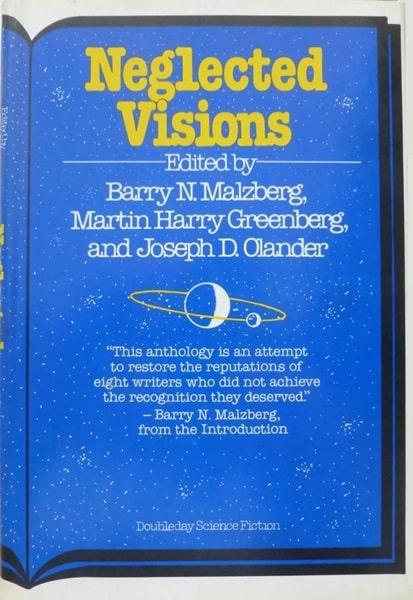

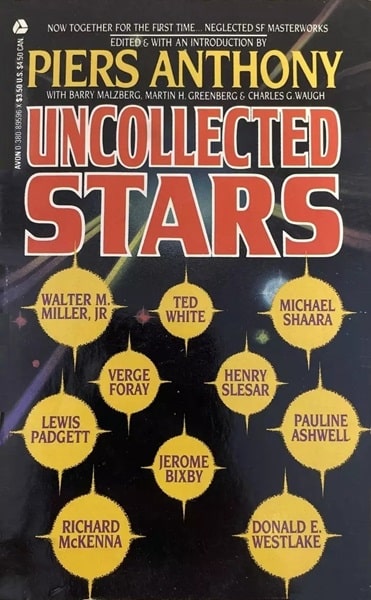

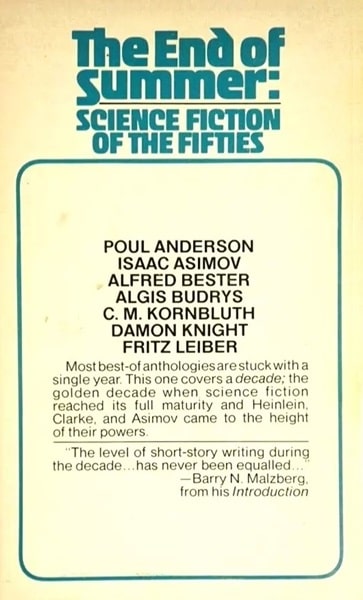

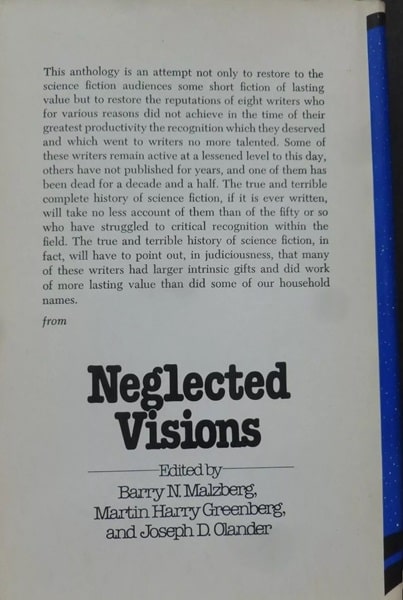

These are The End of Summer (1979, with Pronzini), Neglected Visions (1979, with Joseph D. Olander and Martin H. Greenberg) and Uncollected Stars (1986, with Greenberg, Piers Anthony, and Charles G. Waugh).

|

|

|

|

|

|

The End of Summer, edited by Barry N. Malzberg and Bill Pronzini (Ace Books, June 1979),

Neglected Visions, edited by Malzberg with Joseph D. Olander and Martin H. Greenberg ((Doubleday,

October 1979), and Uncollected Stars, edited by Piers Anthony, Martin H. Greenberg, Barry N. Malzberg,

and Charles G. Waugh (Avon, February 1986). Cover art: David Egge, One Plus One Studio, unknown

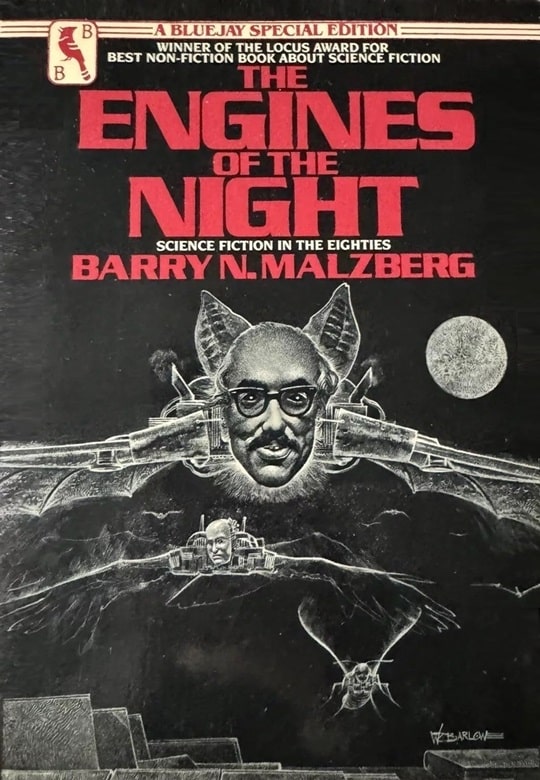

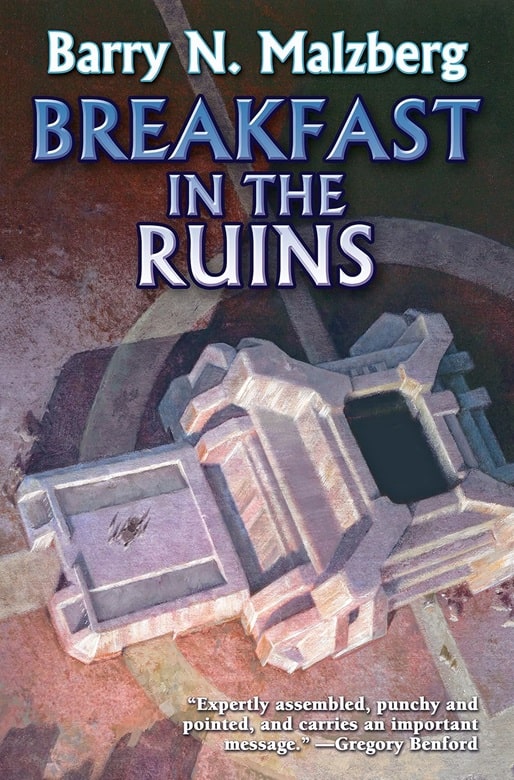

Barry also wrote extensively about science fiction, and about its promise and its failures. Two collections — The Engines of the Night, and its expanded version, Breakfast in the Ruins, were nominated for Hugos, and won Locus Awards. His views were not quite cynical — for a truly deep and abiding love for the field shone through everything he wrote — but they were often despairing. He railed against the failure of writers (and publishers) to reach the potential he saw in science fiction. His ambition remained to the end, as did a dark sense of humor.

Malzberg was in his unique way a true giant in our field. Barry himself, in his later years, seemed to regard his career as a failure, but it was no such thing. He may have stopped publishing novels out of a feeling the publishing world wasn’t receptive to his work, but the best of what he did publish is outstanding, and thoroughly representative of his own vision; and his later short stories never failed to hold the interest. His early SF influenced many writers, and for all Barry’s own saturnine nature, he definitely succeeded in leaving the SF field a better place for his efforts.

|

|

The Engines of the Night: Science Fiction in the Eighties (Bluejay Books,

September 1984), and Breakfast in the Ruins: Science Fiction in the Last Millennium

(Baen Books, April 2007). Covers by Wayne Barlowe and Stephen Hickman

Barry N. Malzberg will be profoundly missed. I will certainly miss his occasional emails — either chiding me on my failure to recognize the virtues of certain stories or writers, or happily endorsing my praise of a story that he too liked. His knowledge of SF was broad, his love was intense, and conversation involving.

And for all his reputation as a curmudgeon (partly I think a construct, as with many curmudgeons) he was good and supportive company, either online as I knew him, or in person, in the testimony of his friends.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a review of The Owlstone Crown by X. J. Kennedy. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over 200 articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

Rich,

Thanks for the fine write-up on one of the most important SF writers of the 20th Century.

Although he dabbled extensively in other fields, I always viewed Malzberg as a “true believer” — someone whose love for the field was unmistakable, and who devoted the majority of their professional career to science fiction. I put only a handful of others in the same category: Isaac Asimov, Lin Carter, Gardner Dozois, Terry Carr, Donald Wollheim, Harry Harrison, David Hartwell. His death is a major loss.

Absolutely one of the great ones, and a writer with a completely individual voice and point of view. His best work simply could not have been written by anyone else. The last thing of his I read (at about this time last year) was Lady of a Thousand Sorrows, a bizarre paranoid roman a clef about a Jackie Kennedy Onassis figure beset by sinister manipulations and shadowy assassins. It was startlingly bold and original, which I could say about virtually everything I ever read by Malzberg.

He is simply irreplaceable.