The Unfulfilled Superhero: Philip Wylie’s Gladiator

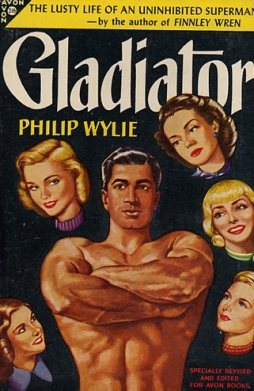

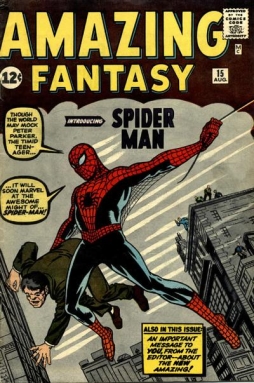

Growing up reading superhero comic books, it was almost inevitable that I’d hear about Philip Wylie’s 1930 novel Gladiator. It was said to be the inspiration behind Superman, the original story about an ultra-powerful strong man who set about trying to right wrongs. Growing older, I heard more: that Jerry Siegel, Superman’s co-creator, had reviewed the book for a fanzine; that he’d swiped dialogue from the book for use in his comics; that Wylie had threatened to sue. These claims were, in fact, not true. It is accurate to say that elements of the novel (now in the public domain and freely available online) can be seen in Superman. It’s also true (as Claude Lalumiére observed to me when he sold me his copy of the book) that the novel seems to have had as much or more inspiration on the character of Spider-Man. But as I see it, the book really stands in opposition to the super-hero genre as it later developed; it’s a kind of deconstructing of the genre before the genre had been really created. Unfortunately, I can’t say I find much else to recommend the novel. Still, it’s worth looking at as a curiosity, to see what survived in later works and what was changed — and how those changes transformed the central idea.

Growing up reading superhero comic books, it was almost inevitable that I’d hear about Philip Wylie’s 1930 novel Gladiator. It was said to be the inspiration behind Superman, the original story about an ultra-powerful strong man who set about trying to right wrongs. Growing older, I heard more: that Jerry Siegel, Superman’s co-creator, had reviewed the book for a fanzine; that he’d swiped dialogue from the book for use in his comics; that Wylie had threatened to sue. These claims were, in fact, not true. It is accurate to say that elements of the novel (now in the public domain and freely available online) can be seen in Superman. It’s also true (as Claude Lalumiére observed to me when he sold me his copy of the book) that the novel seems to have had as much or more inspiration on the character of Spider-Man. But as I see it, the book really stands in opposition to the super-hero genre as it later developed; it’s a kind of deconstructing of the genre before the genre had been really created. Unfortunately, I can’t say I find much else to recommend the novel. Still, it’s worth looking at as a curiosity, to see what survived in later works and what was changed — and how those changes transformed the central idea.

Gladiator opens in rural Colorado, with a man named Abednego Danner, a biology professor at a small college. Danner develops a serum that, administered in utero, can make a living creature tremendously fast, strong, and tough. When his wife falls pregnant, he administers the serum to his unborn child, who turns out to be a son named Hugo. The book follows Hugo though his life, as he develops his tremendous strength, goes to college and becomes a football star, struggles to make money, goes off to fight in the First World War, tries to find his purpose, fails to end political corruption, and finally comes to an odd anticlimactic end struck by lightning on a peak in South America while doubting God.

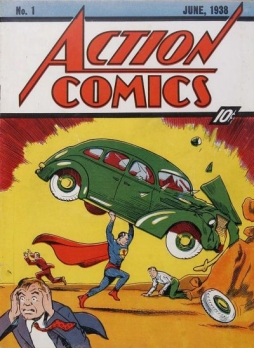

The parallels to Superman are obvious as you read the book, especially if you’re familiar with the early Superman stories — when he was a strongman who could jump instead of fly, before he’d developed heat vision and an array of super-powered enemies. Hugo Danner’s born and grows up in rural America, but spends much of his adult life in the big city. He uses his powers in a football game, much as Superman did in an early issue. He goes to war, as Superman did in some of his first adventures. He outruns a train (or so he tells his father). He even lifts an automobile over his head, as Superman famously did on the cover of his first appearance. Descriptions of Hugo’s feats as a child seem to foreshadow Superboy, who didn’t come to comics until 1945.

The parallels to Superman are obvious as you read the book, especially if you’re familiar with the early Superman stories — when he was a strongman who could jump instead of fly, before he’d developed heat vision and an array of super-powered enemies. Hugo Danner’s born and grows up in rural America, but spends much of his adult life in the big city. He uses his powers in a football game, much as Superman did in an early issue. He goes to war, as Superman did in some of his first adventures. He outruns a train (or so he tells his father). He even lifts an automobile over his head, as Superman famously did on the cover of his first appearance. Descriptions of Hugo’s feats as a child seem to foreshadow Superboy, who didn’t come to comics until 1945.

But there’s also much foreshadowing of Spider-Man. At one point in the book, Hugo’s in New York City and needs money. So he signs up for a boxing match offering money to any man who can go three rounds with the local champ — almost exactly one of the same challenges Peter Parker undertook after he gained his powers. Tonally, the book has slightly more in common with Spider-Man than Superman: much of the book follows Hugo as a young man, trying to figure out what he’s going to do with his gifts. And here’s a fascinating passage early in the book, in which Abednego explains to Hugo how he became so strong, and advises him what to do with his powers:

“Did you ever watch an ant carry many times its weight? Or see a grasshopper jump fifty times its length? The insects have better muscles and nerves than we have. And I improved your body till it was relatively that strong. Can you understand that?”

“Sure. I’m like a man made out of iron instead of meat.”

“That’s it, Hugo. And, as you grow up, you’ve got to remember that. You’re not an ordinary human being. When people find that out, they’ll — they’ll —”

“They’ll hate me?”

“Because they fear you. So you see, you’ve got to be good and kind and considerate — to justify all that strength. Some day you’ll find a use for it — a big, noble use — and then you can make it work and be proud of it. Until that day, you have to be humble like all the rest of us. You mustn’t show off or do cheap tricks. Then you’d just be a clown. Wait your time, son, and you’ll be glad of it. And — another thing — train your temper. You must never lose it. You can see what would happen if you did? Understand?”

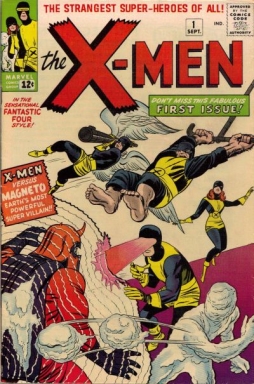

How many superheroes can you see in that exchange? The father giving moral advice to his super-strong son is like Jonathan Kent to Clark, even if the son is a man of iron and not steel. The relative strength of ants and grasshoppers aren’t far from the proportional strength of a spider. And a super-powerful man feared and hated by a world that doesn’t share his powers is an idea at the heart of the X-Men. When Hugo dies at the end of the book, it comes as he contemplates using his father’s invention to create a whole generation of super-powerful children — “the new Titans, the sons of dawn” — but then, he thinks, “humanity was content; it would hate his new race.”

So Hugo soon turns away from this idea, for no particular reason, and goes off to be struck down by God. By this point in the book, he’s either failed at whatever he’s tried or else found that success was hollow. The ordinary humans all about him drag him down; so when he takes a job as a steelworker, he gets fired because he makes his less-powerful co-workers look bad. There’s an odd Ayn Randian feel to much of Hugo’s story, the ultimate example of the supremely gifted individual done in by a dull average collectivist society. Here’s Hugo reflecting to himself in World War One:

So Hugo soon turns away from this idea, for no particular reason, and goes off to be struck down by God. By this point in the book, he’s either failed at whatever he’s tried or else found that success was hollow. The ordinary humans all about him drag him down; so when he takes a job as a steelworker, he gets fired because he makes his less-powerful co-workers look bad. There’s an odd Ayn Randian feel to much of Hugo’s story, the ultimate example of the supremely gifted individual done in by a dull average collectivist society. Here’s Hugo reflecting to himself in World War One:

If he could but have ended the war single-handed, it might have been different. But he was not great enough for that. He had been a thousand men, perhaps ten thousand, but he could not be millions. He could not wrap his arms around a continent and squeeze it into submission. There were too many people and they were too stupid to do more than fear him and hate him. Sitting there, he realized that his naive faith in himself and the universe had foundered. The war was only another war that future generations would find romantic to contemplate and dull to study. He was only a species of genius who had missed his mark by a cosmic margin.

Wylie’s novel isn’t the story of a powerful man who can make a difference. It’s the story of a powerful man made impotent by a world filled with organisational structures, with machinery, with teeming millions. There’s no place in this world for a supremely physically-gifted man, is the book’s message. Hugo never finds his niche, never fulfills his potential for greatness.

The problem is, it’s a little difficult to believe. A little thought produces a list of things at which Hugo would have a real advantage, even outside of combat (test pilot, say, or deep-sea diver — at one point in the novel he casually makes a fortune for himself pearl diving). And in fact when Hugo does finally decide to invade Germany single-handed, the only thing that stops him is the declaration of the armistice that ended the war. It is true that Abednego’s formula wasn’t designed to increase Hugo’s intellect, but the fact is you can’t help but think he’s not the brightest of individuals.

The problem is, it’s a little difficult to believe. A little thought produces a list of things at which Hugo would have a real advantage, even outside of combat (test pilot, say, or deep-sea diver — at one point in the novel he casually makes a fortune for himself pearl diving). And in fact when Hugo does finally decide to invade Germany single-handed, the only thing that stops him is the declaration of the armistice that ended the war. It is true that Abednego’s formula wasn’t designed to increase Hugo’s intellect, but the fact is you can’t help but think he’s not the brightest of individuals.

Or, perhaps more directly and more crippling for the novel, that he’s not the most driven of characters. He drifts from event to event, from place to place, never quite fitting in and never really happy to push himself to his limits. When faced with the slightest obstacle that can’t be solved with physical exertion, or indeed that even looks like it might not be solved by physical exertion, he gives up. As Randian ubermensch, he’s a failure precisely because he has no strong desire, no drive to succeed. His fault lies less in the world surrounding him than in himself.

Hugo’s main motivation is to find somewhere to fit in. But it’s not a terribly strong motivation, as we see by how easily he’s discouraged. And Wylie’s not a good enough writer to make up for a dull central character (this was in fact his first novel, though it was published third since Wylie didn’t want to be established as a science-fiction author). Hugo’s dullness is matched by the dull and unsurprising language of the book. Look at that passage about the war: short, simple statements, no ambiguity, no nuance. It’s direct and clear, but uninteresting. And, over the course of a novel, repetitive.

Hugo’s main motivation is to find somewhere to fit in. But it’s not a terribly strong motivation, as we see by how easily he’s discouraged. And Wylie’s not a good enough writer to make up for a dull central character (this was in fact his first novel, though it was published third since Wylie didn’t want to be established as a science-fiction author). Hugo’s dullness is matched by the dull and unsurprising language of the book. Look at that passage about the war: short, simple statements, no ambiguity, no nuance. It’s direct and clear, but uninteresting. And, over the course of a novel, repetitive.

Since Hugo lacks a strong central drive, he drifts along in life, and hence in the novel. The result is an episodic, rambling plot. The thematic bonds are both too few and too unsubtle to tie the book together. Hugo’s simply not interesting enough as a character to hold the reader’s interest. His failures are uninteresting and repetitive, because he’s uninteresting and incapable of growth. In a sense, he’s lacking exactly what his famous offspring possess.

You can say that the super-hero is a power fantasy, and that the characters are by nature upbeat in a way that Hugo Danner’s story can’t be. But at the same time, Superman, Spider-Man, and the X-Men between them have I think aspects of their personalities that are dramatically interesting in a way that Hugo isn’t. They’re strong-willed, to start with. But that strength of will has a specific purpose: to right wrongs, to help people. Hugo never develops a social conscience on that level. He takes a stab at fighting government corruption, but in a hopelessly direct and ineffective way; typically, as soon as he sees the scope of the problem, he gives up.

Superman, fairly consistently since the character’s introducion, has a strong drive to make the world a better place. He has an idealism (however ham-fistedly it’s often been expressed) that Hugo doesn’t. As a character he may seem unrealistic, but in fact those seeming contradictions are what make him interesting: why does he do what he does, when he could do anything? What makes him feel so strongly about a world from which he is in so many ways removed? Answering these questions has given writers material for decades. The same thing for Spider-Man, and more: Spider-Man, from Ditko’s run onward, has grown and changed as a character. That’s less true over the last twenty years, perhaps, but under Ditko he started as a high-schooler and ended as a university student with a job as a freelance photographer. He learned, in his very first story, that responsibility must come with power, and kept learning and growing over the stories that followed. Again, his contradictions made him interesting; his sense of ideals led to conflict, drama, and development. The X-Men, like Hugo Danner, faced a world that feared and hated them — but they decided to save it. That sense of mission gave them purpose.

Superman, fairly consistently since the character’s introducion, has a strong drive to make the world a better place. He has an idealism (however ham-fistedly it’s often been expressed) that Hugo doesn’t. As a character he may seem unrealistic, but in fact those seeming contradictions are what make him interesting: why does he do what he does, when he could do anything? What makes him feel so strongly about a world from which he is in so many ways removed? Answering these questions has given writers material for decades. The same thing for Spider-Man, and more: Spider-Man, from Ditko’s run onward, has grown and changed as a character. That’s less true over the last twenty years, perhaps, but under Ditko he started as a high-schooler and ended as a university student with a job as a freelance photographer. He learned, in his very first story, that responsibility must come with power, and kept learning and growing over the stories that followed. Again, his contradictions made him interesting; his sense of ideals led to conflict, drama, and development. The X-Men, like Hugo Danner, faced a world that feared and hated them — but they decided to save it. That sense of mission gave them purpose.

You can say that these are children’s stories; but the point is that they’re really good children’s stories. Gladiator’s an attempt at a mature novel, but it fails. Wylie’s writing is nowhere near good enough to overcome his passive main character. Conceptually, you could maybe get good mileage out of an antihero like Hugo — as I said at the start, he reads like a deconstruction of the super-heroic ideal, someone who’s given great power and feels some responsibility to use it, but never figures out how. The bleak, downbeat tone contrasted with Hugo’s great potential could have been, in the hands of a better writer, something worth exploring. As it is, though, you read the book and all you can think about is what it’s missing: meaningful conflict, clever language, an interesting central character. As a forerunner to the super-hero genre, it’s fascinating in the way it unerringly identifies a crucial component of what makes the genre work, and then completely expunges that element.

Gladiator would be largely forgotten today if not for the story of its influence on super-hero comics. I can’t say that’s unjust. It is possible that the greater success of Superman and his colleagues came because they were brighter and had an element of wish-fulfillment more likely to appeal to a large audience — but it’s also possible that, regardless of wish-fulfillment, they spoke more clearly and in a more dramatic fashion. There’s a sense in which Gladiator might be more relevant now, as an alternative to the sometimes too-easy heroism of the superfolk, but the writing is simply not good enough for the book to survive as more than a curiosity. In a world with Watchmen in it, Gladiator seems almost beside the point.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] can talk about the Hulk as a take on Jekyll and Hyde, or Nick Fury as a superhero James Bond, but the more you see and read of popular culture in the first half of the twentieth century the more you can see ideas […]