Little Madhouse on the Prairie: Wisconsin Death Trip

Like many of you, I own a lot of books. Like perhaps not quite as many of you, I own a lot of very strange books, among them Aleister Crowley’s autobiography, a volume of Criswell’s predictions, a collection of “poems” by Victor Buono (he was King Tut to Adam West’s Batman; the title of his book is It Could Be Verse), a paranoid little volume called The Enemy Within that showed up one day on every driveway in my neighborhood in a rock-weighted plastic bag, and that blames literally everything bad that’s ever happened on the Jesuits (I’m probably the only person in town who actually read it — God, I hope I’m the only person in town who actually read it), the Exegesis of Philip K. Dick (the Lord talked to Phil, and boy, did they have some weird conversations), the collected works of Charles Fort, several volumes of the Shaver Mystery… it goes on and on.

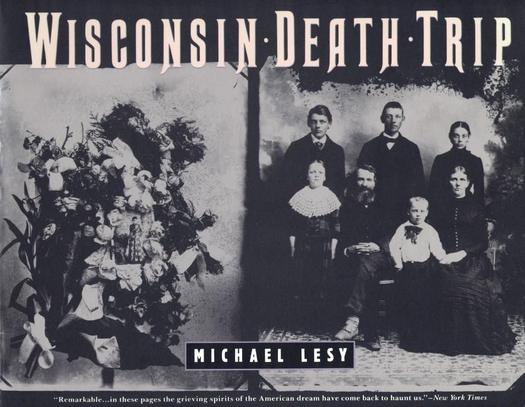

There is no stranger book on my shelves, though, than Wisconsin Death Trip. Catchy title, huh?

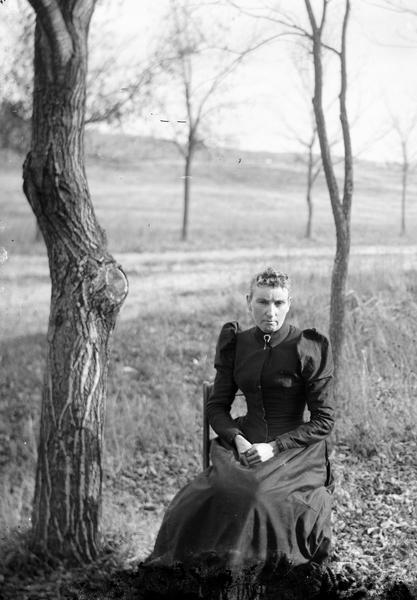

Written by Michael Lesy in 1973 (but assembled or compiled more than written), the book chronicles the years 1885 to 1900 in and around the town of Black River Falls, Wisconsin. It uses contemporary photographs taken by Charles Van Schaick (a “careful, competent town photographer”) and short excerpts from stories that appeared in the local newspaper, the Badger State Banner, written by editor Frank Cooper and his son George (“equally competent, equally careful, equally experienced town newspaper editors”), to give us the dark underside of one of America’s foundational myths — the story of the brave, hardy, cheerful pioneers who overcame every obstacle and supported each other through every trial, thereby bringing the blessings of civilization to what was once a savage and trackless wilderness.

Wisconsin Death Trip pushes back on that comforting narrative, rendering a grim — indeed, virtually gothic — portrait of a time and place in our history that has long been idealized and prettified. It is as if Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books were rewritten by Charles Brockden Brown or the Edgar Allan Poe of “The Tell-Tale Heart” or “The Premature Burial” (a ghastly fate that several people in Wisconsin Death Trip narrowly escape — or fail to escape).

Instead of joining together as families or communities to bake pies, celebrate holidays, reap harvests or raise barns, the people of this frontier commit murder, incest, vandalism and arson, and instead of making it through hard times with the ready help of family and neighbors, they despondently quaff carbolic acid, drown themselves in lakes, or hang themselves from the rafters of their barns.

Instead of providing social and economic stability for the town, bankers embezzle funds and their institutions go bust, wrecking the lives of farmers and small businessmen. Instead of providing a healthful contrast to dirty, overcrowded cities, the district is continually stricken by diphtheria epidemics that fall out of a clear sky like malign asteroids, wiping out whole families in a matter of days or even hours. Instead of being an oasis of prosperity and opportunity, the region suffers from an inherently unstable economy and unemployment is endemic; roving gangs of “tramps” bully, extort, and terrorize, and those who deny them a handout may get up in the morning to find that the throats of all their livestock have been cut.

In this roiling cauldron of privation and misery, three things stand out as the emblematic essence of Wisconsin at the end of the nineteenth century (at least in the pages of Wisconsin Death Trip): arson, suicide, and insanity. Most of the newspaper stories that Lesy selected deal with one or more of these three aberrations.

Arson was apparently a cheap and easy way to exact revenge against individuals or against society as a whole, or perhaps it was merely a way to find some excitement in an otherwise stultifying and monotonous environment:

Seventeen business buildings and residences were burned at Montfort, Grant County, the other morning. The business part of the village was practically wiped out… It was Montfort’s second fire in 8 weeks and it was believed incendiaries were at work.

Each year holds countless examples of these malicious conflagrations, and often when people weren’t destroying structures by fire, they were exterminating themselves by any means available:

Miss Minnie Rose of Beaver Dam shot herself in the Plankton House in Milwaukee. She left a letter in which she asks that her body be destroyed by electricity… In the letter she says that untrue stories circulated about her drove her to suicide.

People shot themselves, hung themselves, poisoned themselves (the previously mentioned carbolic acid seemed to be a favorite — if the word can be used — method), starved themselves, drowned themselves, cut their own throats, and even set themselves on fire.

These suicides had many apparent causes — crushing poverty, despair over business failures, prolonged unemployment or other economic reverses (weighing especially heavily on those with families to support, unsurprisingly), failed love affairs, long stretches of bad luck, illness, religious mania, and a terror of the hardships of old age are all cited in these accounts.

In addition to many newspaper items that describe people gripped by the various psychoses that seem to have been startlingly widespread, Lesy fills the book with extracts from the records of the Mendota State Hospital, the local institution to which such unfortunates were consigned, and these accounts attest to the third theme that runs through Wisconsin Death Trip (often also appearing in the reports of arson and especially suicide) — insanity:

Admitted January 20th, 1896. Town of Garfield. Age 52. Norwegian. Married. Two children, youngest 19 yrs. old. Farmer. Poor. Illness began 10 months ago. Cause said to be his unfortunate pecuniary condition. Deluded on the subject of religion. Is afraid of injury being done to him. Relations say he has tried to hang himself… September 29, 1896: Discharged… improved… Readmitted May 4, 1898: Delusion that he and his family are to be hanged or destroyed.

One can only speculate about the probable hard fate of that poor farmer’s family. Of course, in so loose-knit a society, many mentally ill people managed to avoid Mendota and simply ran around loose:

A wild man is terrorizing the people north of Grantsburg. He appears to be 35 years of age, has long black whiskers, is barefooted, has scarcely any clothes on him, and he carries a hatchet. He appeared at several farms and asked for something to eat. He eats ravenously, and when asked where he came from, points to the east. He secretes himself in the woods during the day and has the most bloodcurdling yells that have ever been heard in the neighborhood.

In addition to the appalling, matter-of-fact newspaper accounts of these everyday calamities (perhaps all the more appalling because of their matter-of-factness), Wisconsin Death Trip is… enlivened isn’t the word… let’s say it’s leavened with Charles Van Schaick’s photographs. Most are posed pictures of individuals and family groups, and in subject and sensibility are black and white, glass-plate equivalents of Grant Wood’s American Gothic, now and then bringing to mind the deadpan grotesques of Diane Arbus. Smiles or any hint of the casual are rare (though not completely absent), but the occasional whimsical or eccentric image (like the one of a smiling young woman entwined in snakes) is far outweighed by stolid, darkly-dressed, bleakly staring people, and the selections are sometimes seasoned with that morbid staple of nineteenth century sentiment, dead babies in their coffins.

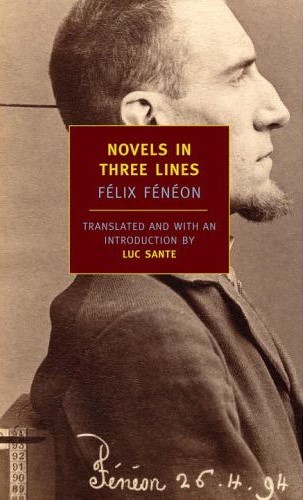

All in all, it’s a book unlike any other that I can think of. Perhaps its nearest relative is Novels in Three Lines, a collection of very short newspaper items written by the aesthete and anarchist Félix Fénéon that first appeared in 1906 in the French newspaper Le Matin, but while Fénéon’s pieces often correspond with the stories in Wisconsin Death Trip in subject, they are miles apart in sensibility. Here are two accounts of similar horrors, the first from Wisconsin Death Trip, the second from Novels in Three Lines:

Mrs. John Larson, wife of a farmer living in the town of Troy, drowned her 3 children in Lake St. Croix during a fit of insanity. Her husband, on finding her absent from the house, began a search and found her at the lake shore… 2 of her children lying in the sand dead. The third could not be found. Mrs. Larson imagines that devils pursue her.

Blindfolded, three Farons, ages 2, 4, and 6, were thrown into the Saône by their mother, a madwoman, who joined them.

The Coopers’ piece is earnest and sober, striking a note of straightforward pathos, while Fénéon’s has a chill to it; rather than being empathetic, it’s ironic and sardonic, less a sad slice of human interest than an opportunity for Fénéon to display his wit — you can almost hear a rim shot on the final phrase. The only moments when Wisconsin Death Trip arches its eyebrows are provided by Michael Lesy himself, when he juxtaposes grim accounts of despair and madness with upbeat high school class mottoes, like this one from 1900: “We Have Reached the Hills; the Mountains Lie Beyond” or this from 1896: “Vim, Vigor, Victory.”

There’s only one outright laugh in the book, for me at least — a story about someone suffering from what we would call cabin fever describes the man as having gone “shack-wacky”, a priceless expression which has entered my permanent vocabulary.

So what is Wisconsin Death Trip for? What does it all mean? In an extended conclusion, Lesy offers his own interpretation of the horror show he’s just presented to us, an interpretation based on two linked explanations for all the despair, disorder, and death: on a social level, Lesy provides a material explanation in terms of Marxist economics and on the individual level, he gives a psychological explanation in terms of Freudian psychology (Lesy describes much of the arson and insanity as classic paranoid or obsessive-compulsive behavior). He obviously thought very seriously about the significance of this awful material, and as explanations go, his is admirable.

It just doesn’t explain anything. Or perhaps it’s fairer to say that it both explains too much and not enough, a common fault of mechanistic interpretations of human life.

That doesn’t matter much, though; what stays with you when you close the book is not any explanation or interpretation, however carefully constructed or convincingly argued. You finally turn away from Wisconsin Death Trip not persuaded by any thesis, but wrenched into a state that comes close to awe, and all because of the raw actuality of what you’ve just witnessed. The value of the book lies in the statement that Lesy begins it with: “The pictures you are about to see are of people who were once actually alive. The excerpts you’re about to read recount events these people, or people like them, once experienced.” This extraordinary book makes these long-dead people and their experiences as vivid and present as the events of our own daily lives, and it’s a unique and startling achievement.

Paradoxically enough, the ultimate effect of reading Wisconsin Death Trip may be to experience a kind of affirmation: how brave and stubborn and tenacious people are! Like an overmatched fighter continuing to get up from knockdown after knockdown until his opponent gives up out of sheer frustration, people kept coming and kept coming and the wilderness did indeed get settled even in the face of catastrophes like this (which, Lesy reminds us, were so common as not to be considered at all shocking by the Coopers’ original readers):

The malignant diphtheria epidemic in Louis Valley, La Crosse County, proved fatal to all the children in Martin Molloy’s family, 5 in number. Three died in a day. The house and furniture were burned.

To put ourselves in the place of a person like Martin Molloy, who found himself homeless and childless in a single afternoon, cannot help but broaden our view of the past while deepening our imaginative sympathy, and painful as contemplating such an unspeakable tragedy may be, it may well lead to a greater appreciation of both the precariousness and preciousness of life.

Does Wisconsin Death Trip tell us the complete truth about its time and place? It certainly gives us a truth, one that has remained buried and neglected for too long, but is it the only truth? Any account can only be a partial one, and while the book supplies some missing pieces to a puzzle so large that it can never be completed or viewed as a whole, they are not the only pieces. (Were there really no family jokes, no tender marriages, no happy, healthy children, no successes of any kind in Black River Falls in those years?) Laura Ingalls Wilder and others like her completed their corner of the puzzle, and Lesy, with Van Schaick and the Coopers, have completed theirs, and neither corner is the whole picture, which is beyond our comprehension because its subject is life itself in all of its contradictory beauty and ugliness, joy and sorrow, happiness and misery, hope and despair.

The American poet Randall Jarrell (himself a suicide) once said, “It is absurd not to call the world evil, and it is impossible to take the condemnation seriously; either laughter or tears are impossibly inadequate, we have for it only the stare we give Medusa’s head.” All of which is to say that life is a house large enough to accommodate everything conceivable in its countless rooms, and for those of us who live in a comfortable quarter of the residence, there can be great value in passing through forgotten doors to see what disquieting things those distant chambers may hold, for they are places in which people much like us have lived and died. Reading Wisconsin Death Trip is one way of making such an excursion, and it’s a trip worth taking.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Roger Corman, April 5, 1926 – May 9, 2024

I recently read Willa Cather’s “My Antonia”, a chronicle of life in Nebraska in the late 19th century. While not nearly as grim as “Wisconsin Death Trip” seems to be, it has its share of crushing poverty, two suicides, crazy guys wandering around, affairs and such.

One thing that really jumps out about it is that while the people in “My Antonia” are willing to help their neighbors, they do so with a certain caution; a worry that trying to help your poor/unlucky neighbors will make your poor/unlucky yourself. Also interesting is how different each individual farmer’s situation is. Jim’s (the narrator) grandparents are quite successful, living in a house and hiring helpers, their neighbors are still living in a dugout (which is a fancy word for a hole in the ground), and barely getting by.

On top of that, the life of people in town is completely different from the farmers.

One other bit, re: suicide. I went to Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains and picked up a couple of books by Novelyne Price (who was REH’s girlfriend and friend)—and one of the things she points out in a letter (I think to de Camp) was that it wasn’t like REH was the only person who committed suicide in Cross Plains that year, much less the county itself. He happens to be the one who is famous, and that we know a lot about.

It’s hard to know how isolated these people were or how much support they gave each other – how much of that kind of “good news” made it into the paper? (Then as today, I suspect the natural tendency was to go for the violent, tragic, and sensational.) If any did, it didn’t survive Lesy’s selection process. That’s why I felt I needed to say that we can’t mistake what we see in Wisconsin Death Trip for the whole story.

I haven’t read any Cather, though she’s long been on my “absolutely have to get to it” list. I’m still recovering from Dreiser’s An American Tragedy!

“My Antonia” is quite good–read it so I have someone to talk to about it!

I think another issues back in those days (and even today) is that often you don’t really even know how bad things are going for your neighbors. Your neighbor’s pride (or ignorance, or pig-headed stubbornness,) might keep then from asking for help until it is wayyy to late.

H.P. Lovecraft wrote quite a bit about madness, and many people assume it was because his father and mother went mad (probably from syphilis)– but I think that is only part of the picture–he narrowly avoided going to WWI (he tried to volunteer but his mother ratted him out that he wasn’t old enough), but WWI drove home that people have a breaking point. “Shell Shock” was suddenly a thing. And I think he understood that often by the time people realize they are at their breaking point, they also realize they hit their breaking point about 10 minutes ago.

That’s what I would suspect is going on with many of the cases of “Wisconsin Death Trip”– people push and push and push and don’t realize that they needed to stop pushing, they needed to reach out for help, about a week or two ago. They hit a kind of mental/emotional tipping point.

Owning Crowley’s autohagiography doesn’t seem all that strange to me. I don’t have a copy, but I read it a while back. It seemed almost to be a product of dissociative identity disorder (as the kids are calling it nowadays): the work on one hand of the Great Beast and on the other of a stuffy upper middle class Englishman.

I remember Wisconsin Death Trip from back in the 1970s, when I paged in my town’s public library for 5 years. I thought it was a very strange book to be kept in a library in Fairfield CT, as there was nothing relatable to it in a suburban NYC town.

As far as Novel in Three Lines goes, I actually bought a copy of this about 5 or so years ago to a review I had read online somewhere. Reading it was like the 19th century equivalent of elevator pitches that writers would do for a Lifetime Channel film or a pitch to an editor of a national tabloid newspaper.

Please know:

Most of my family perished in the Holocaust.

What I discovered in Wisconsin was a Holocaust without Jews.

As to the book itself: It was built/designed/sequenced to be a collage that allowed its viewers/readers to reassemble it in retrospect.

Making an image/text book is–inevitably– an artistically risky business. WDT was an artistic failure because its the stories told by its text overwhelmed the stories told by its images. Though every element in the book,visual and verbal,was carefully sequenced,the ” sound” of its text played louder than it images.

I’ve spent the last fifty years making other books, trying to solve this problem.

Mr. Lesy, I’m amazed – and gratified – that you took the time to comment on my rambling thoughts about your book. I can only say that it affected me deeply, and while your judgment of Wisconsin Death Trip’s achievement has to carry more authority than anyone else’s, I certainly don’t consider it an artistic failure.

May I ask what books have you done that you think more successfully “solved the problem” of the text/image blend?

“REAL LIFE”

“LONG TIME COMING”

“LOOKING BACKWARD”

“SNAPSHOTS”

“WALKER EVANS”

The problem is a Rubik’s Cube problem. Viewer/readers work the cube. The solutions are provisional.

They happen–briefly—in retrospect in the minds of the books’ reader/viewers,based on (1) the images and facts I’ve assembled (2) how I’ve sequenced them and (3) how I’ve narrated them.

There are many contemporary image/text books that are more poetic than mine.

I suggest you take a look at some of the stuff that MACK BOOKS or LOOSE JOINTS have been publishing.

My ambition : To make image/text books that stimulate associative AND analytic thinking. All at once.

It’s like trying to re-invent the wheel.

Best wishes–

M.Lesy