Remembering Carl Jacobi

|

|

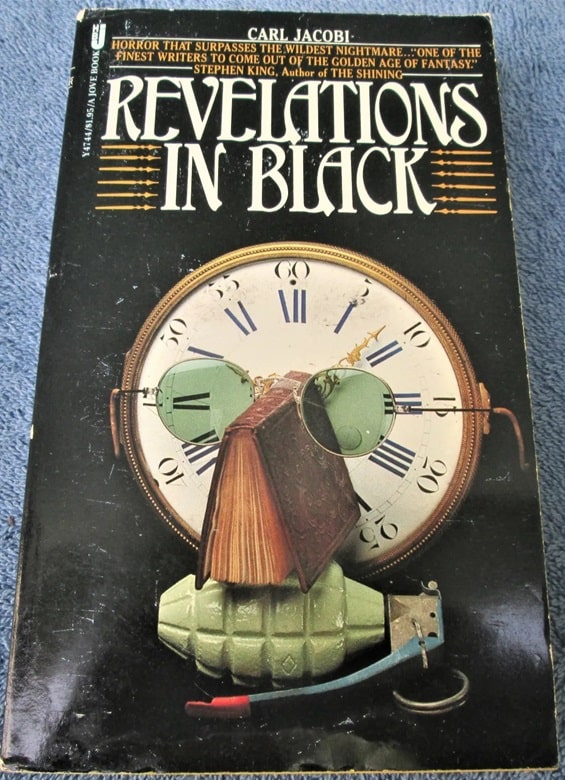

Revelations in Black by Carl Jacobi (Jove/HBJ, January 1979). Cover uncredited

D.H. Olson delivered this eulogy for Carl Jacobi on Friday, August 29, 1997 at Lakewood Chapel in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It was included in Masters of the Weird Tale: Carl Jacobi, published by Centipede Press in May 2014. Our deepest thanks to D.H. Olson for permission to reprint it here, and special thanks to Jerad Walters at Centipede Press for providing the text.

When R. Dixon Smith asked me to speak here today, I was honored, but also somewhat taken aback. There are others, after all, who have known Carl Jacobi both better, and longer, than I. Still, when one is asked to do honor to a man whom one has admired for years, one can hardly say no.

First, to the “facts” as they may be found in the public record.

|

|

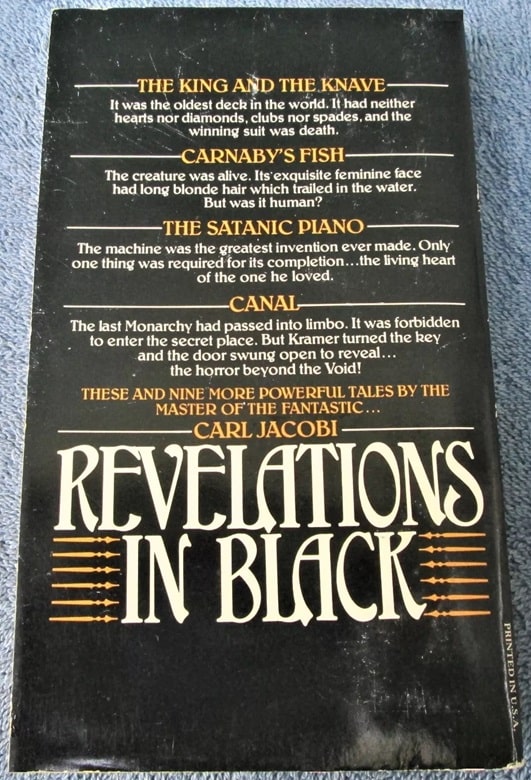

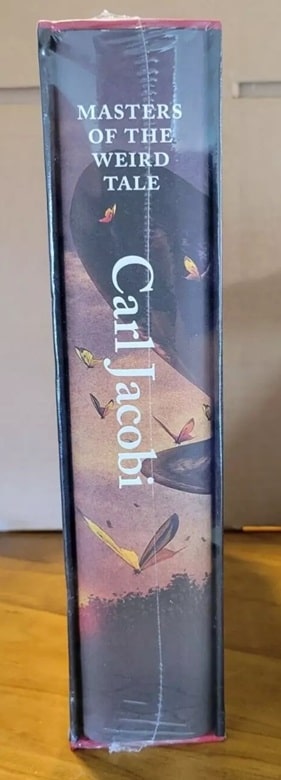

Masters of the Weird Tale: Carl Jacobi (Centipede Press, May 6, 2014)

Carl Richard Jacobi was born in Minneapolis on July 10, 1908, the only child of Richard and Meta Jacobi. He attended Bryant Grade School, Bryant Junior High, and, later, Central High School. From early childhood he exhibited a love of books and writing, and even before leaving Bryant, he was making money from his writing — selling his classmates his handwritten “novels” at ten cents apiece. At Central High, Carl took the next step toward as a career as an author, placing several stories in The Quest, the school’s literary magazine. It was also during this time that Carl discovered Weird Tales, a magazine which would be a major factor, both directly and indirectly, in his later career.

In 1927, Carl enrolled at the University of Minnesota, where he quickly became an important figure in the school’s then-burgeoning literary scene. He served on the staff of the Minnesota Daily and as an editor for both The Minnesota Quarterly, the school’s literary journal, and Ski-U-Mah, the campus humor magazine.

He also contributed to those publications. One of his best known stories, “Mive,” first appeared in The Minnesota Quarterly. When it was reprinted four years later in Weird Tales, the first of many such appearances in that magazine, Carl found himself on the receiving end of heartfelt praise and comments from such authors as H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, and Robert E. Howard.

Carl’s time at the University is notable for two other developments as well. The first was his introduction to Donald Wandrei. The second was his first professional sale, “Rumbling Cannon,” a Stephen Benedict adventure, to Secret Service Stories. In what may be seen as a warning to all aspiring authors, Secret Service Stories went out of business soon thereafter and Carl was never paid for the use of his story.

Front Row L to R: Crispin Burnham, Chris Hawes, Chris Sherman. Middle Row L to R:

Donald Wandrei, Carl Jacobi, Joe West, Richard Tierney. Back Row: Jack Koblas at

Jack Koblas Home, Minneapolis, 1970s. Photograph by Eric Carlson.

Nevertheless, one cannot stop a writer from writing — and Carl was a writer, born and bred. After leaving the University in 1930, Carl took a job as a reporter with the Minneapolis Star. His real love was fiction, however, and he quickly left the Star, determined to make his way as a freelance author. He rented an office at the intersection of Lake and Lyndale, moved in his typewriter and a ream of paper, and started to turn out stories as fast as he was able.

Even then, Carl was hardly your typical pulp author. While most of his contemporaries judged their success by the number of words produced, Carl judged his by the quality of those words. Such attention to detail is one of the reasons why Carl’s fiction has stood the test of time, while that of many of his contemporaries has fallen by the wayside. At the same time, such painstaking, time-consuming care made it difficult for Carl to make more than a modest living at his craft.

Nor was there any security in the life of a freelance author. When the health of his parents began to fail, Carl found himself forced to do more and more work outside of the fiction field. At first, these jobs allowed Carl to function as a writer. In 1938, he produced Paths to the Far East, a geography textbook for the Minneapolis Public Schools. In 1941, he served, briefly, as the editor of Midwest Media, a job that required him to write most of that publication’s copy and serve as production manager. Finally, in 1942, the need to provide for his parents became too great. He took a job with Honeywell, and the time he had available for his writing was much reduced. He persevered, but his dream of supporting himself solely through his writing was at an end.

|

|

|

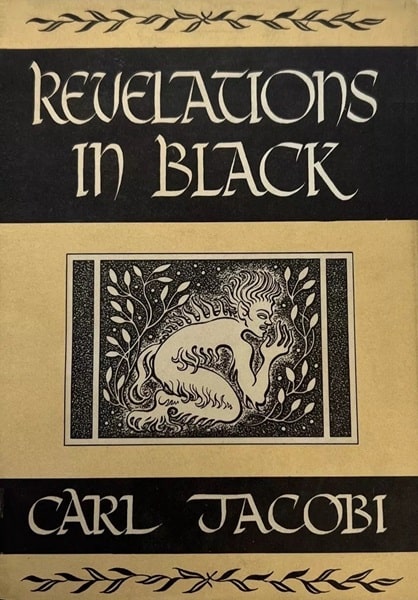

Revelations in Black (Arkham House, 1947). Cover by Ronald Clyne

The Carl of this period was one whom none of us ever knew; but we’ve all seen pictures from that time. My personal favorite is the one that Dixon Smith chose for the frontispiece of his biography of Carl. Taken in 1936, it shows a young man, dressed to the nines. Dapper. Confident. His right foot resting on the running board of his Chevrolet. The caption below, a quote from Jacobi himself, says it all: “My car was new then, and I was new then.”

From 1942 on, Carl’s life proved to be a more frustrating affair. Besides having less time to devote to his writing, he also found that his markets were disappearing. The pulps were dying and being slowly replaced by digest magazines and paperback books. The adventure story, one of Carl’s favorite forms, was likewise falling on hard times. The Weird Tale, another of Carl’s loves, was ailing, kept alive only by Weird Tales magazine and Arkham House Publishers of Sauk City, Wisconsin, a small press founded by Carl’s old U of M associate, Donald Wandrei, and fellow Weird Tales contributor August Derleth.

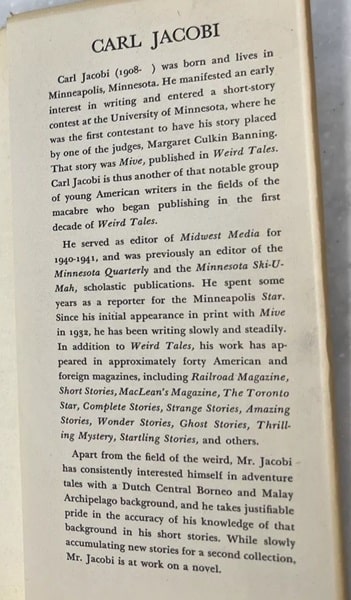

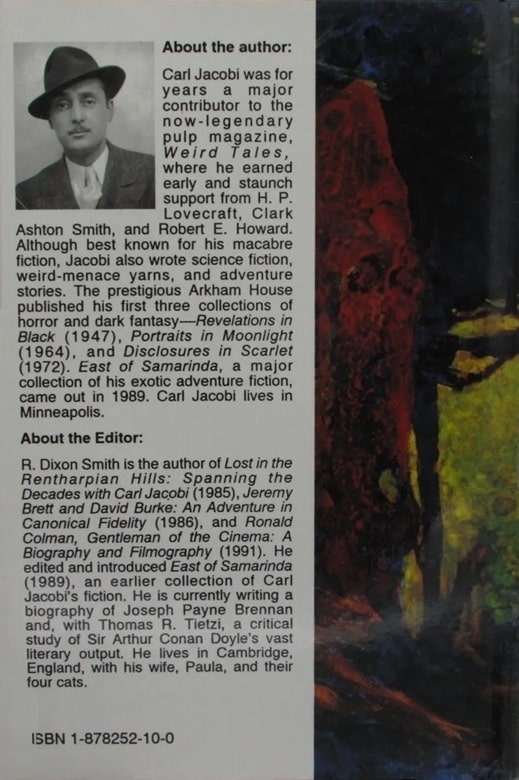

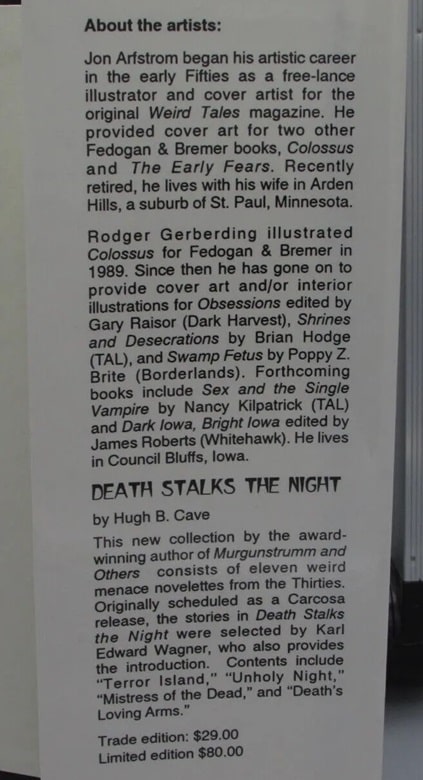

Arkham House would eventually publish three collections of Carl’s stories, Revelations In Black in 1947, Portraits In Moonlight in 1964, and Disclosures in Scarlet in 1972. These volumes, and most particularly the first two, were points of pride for Carl, and he treasured them until the day he died.

As we all know, fate was not kind to Carl Jacobi. The death of his mother and last surviving aunt in 1965 left him truly alone for the first time in his life, and threw him into a 2-year depression. In 1971, he suffered a fall in his home. A seizure, a suspected stroke, was the cause — and Carl had to learn how to walk all over again. Adding insult to injury, his home was burglarized in his absence. In all, he would suffer three such robberies between 1971 and 1976.

Of bigger concern was his own gradually deteriorating health. In the 1940s, Carl had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. As his motor-control decreased, it became increasingly difficult for him to pursue his first love — writing. Luckily for us, Carl was possessed of a single minded determination. His entire life had revolved around writing and he was not about to let his illness get the better of him.

That desire to create, combined with the stubbornness he’d inherited from his father, kept him going long after most others would have given up. As late as the 1980s, Carl was still producing stories, laboriously typing them out, one letter at a time, whenever his fits of shaking subsided enough to allow such work.

|

|

|

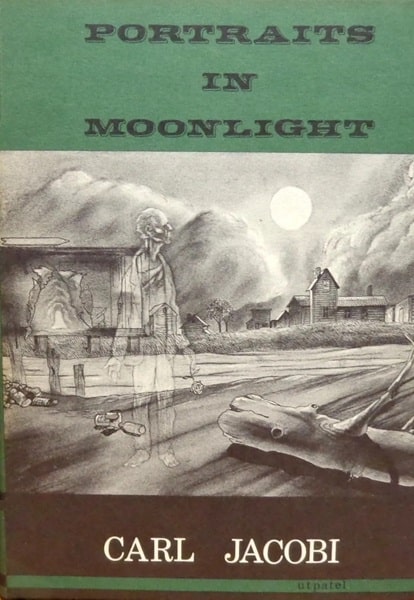

Portraits in Moonlight (Arkham House, 1964). Cover by Frank Utpatel

I first met Carl Jacobi very late in his life. It was the winter of 1986/87 when I accompanied R. Dixon Smith and Andy Decker to Carl’s basement apartment at 3305 Hennepin Avenue. I wasn’t sure what to expect. Just weeks earlier I’d met Donald Wandrei for the first time. Don, as many of you know, was of a secretive nature, jealously guarding his privacy. Jack Koblas, with whom I’d visited Don, had repeatedly drilled into my head, “Whatever you do, don’t look at anything or touch anything.” It is a tribute to Jack’s skill as a coach that weeks later I found myself approaching Carl Jacobi in much the same way I’d been trained to approach Donald Wandrei.

That, of course, was a mistake, for the two men were as different as night and day. While Donald was selective in what he would discuss, Carl was open and gregarious — or at least as gregarious as his health problems allowed him to be. While Donald would have been offended by someone looking at his possessions and mementoes, Carl actively encouraged it. Moreover, he wanted you not just to look, but to touch as well.

By this time, Carl didn’t have much, but I remember three things in particular: a drawing, given to him by a friend and taped to his bedroom door; a foreign language edition of one of his books; and a small black book, handmade by Mary Elizabeth Counselman, to the exact specifications of the volume described by Jacobi in his classic vampire tale “Revelations in Black.” Jack’s “Wandrei training” still held, so when Carl pointed it out to me, I looked, but made no attempt to actually touch it.

I’m not sure what Carl thought of my reticence, but he wasn’t about to let it stand in his way. He wanted me to pick up that book, to look through it. It was one of his prized possessions and he wanted to share it with me. Eventually I relented. I took it in my hands and paged through it. Inside was the text of Carl’s story, clipped from some paperback and painstakingly bound into its cover by Counselman herself.

I never forgot that book and, earlier this week, when I first talked to Carl’s conservator, Michael Scott, one of my very first questions was what had become of it. As you can see, it was something that Carl treasured right up to the end, one of the few items he brought with him into the nursing home. It now rests on the table to my left and I would encourage each of you to look at it for yourselves, and handle it — because I think Carl would have wanted it that way.

As I said, my first meeting with Carl was very late in his life. He could no longer write. His speech was slurred and difficult to understand. He was fast approaching the point where he would no longer be able to live alone. Yet his eyes were as bright and clear as any I’ve ever seen. It was obvious that Carl, for all of his physical infirmities, had lost none of his mental faculties. How frustrating it was, for him and for us, that communication was so difficult.

|

|

|

|

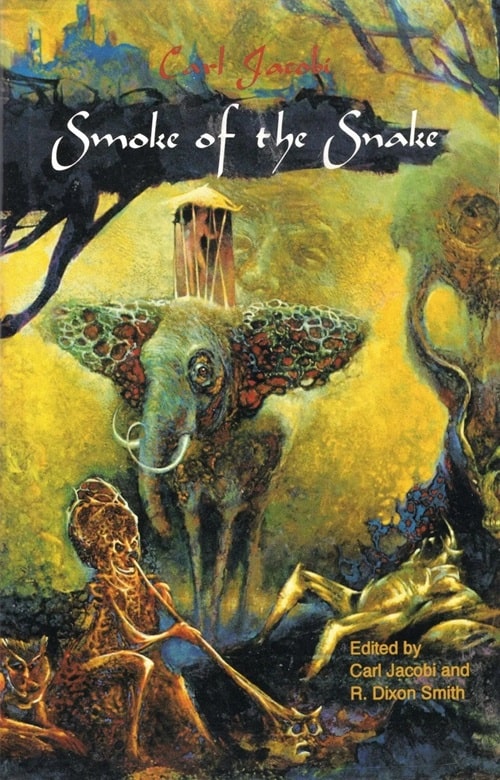

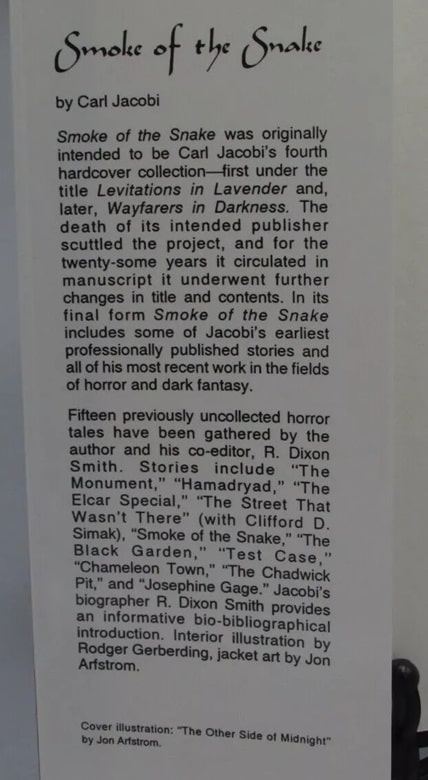

Smoke of the Snake (Fedogan & Bremer, 1994). Cover by Jon Arfstrom

The last time I saw Carl was in August of 1994. Smoke of the Snake had just come out from Fedogan & Bremer and I, Philip Rahman, R. Dixon Smith, and Paula Kirby (Dixon’s then fiancé and, now, wife) drove out to the nursing home to present Carl with a copy of the book.

Carl’s half of the room he shared was quite obviously his. Looking around, one could see his old typewriter; a few of his own books, wrapped in plastic and sitting on a shelf; a bulletin board to which were affixed notes and cards from various friends and well-wishers. A portrait of a woman that I’d remembered seeing in Carl’s old apartment hung on the wall, near the head of his bed.

On the other wall, positioned so that it was always within sight of the bed, was a dresser, atop which rested Carl’s Minnesota Fantasy Award. On the desk by the window, next to the word processor that Carl was never able to master, lay a library copy of Captain Blood by Raphael Sabatini. Carl, despite his deteriorated state, was still able to read — a little at least — and had apparently decided to revisit his roots, as it were, by rereading the work of an author who had always been one of his personal favorites.

Of the rest of that visit I will say little. Carl’s condition had, not surprisingly, gotten much worse over the years. By 1994, he was essentially bed-ridden. His speech, difficult to understand in 1986, was now almost totally unintelligible. Yet, that old gleam in the eyes was still there, in fact Carl’s eyes positively sparkled when Dixon held a copy of the book out for him to see.

I will speak no more of Carl’s condition on that day. Even now it’s not something I care to think of. While I was glad to have been a part of something that brought him joy, I would prefer not to remember the image of Carl as he was in those last years; nor would Carl want us to remember him in that way.

I believe, very strongly, that Carl’s view of himself, right up to the end, was that of the dapper, confident young author, his right foot resting on the running board of a new Chevrolet. So full of life, so full of promise.

|

|

|

|

Disclosures in Scarlet (Arkham House, 1972). Cover by Frank Utpatel

I talked to Hugh Cave immediately after I learned of Carl’s death and he said something quite interesting:

How terrible it must have been for Carl, a writer, a man whose whole life revolved around words, to have ended up as he did, unable to communicate his thoughts to others.

I mention it here because Hugh’s words were perhaps even more true than he suspected. On Wednesday, when Michael Scott and I were going through Carl’s remaining effects, with an eye toward putting together a memorial display, Michael told me an interesting story. Carl, it seems, had never stopped being a writer. When he was no longer able to work his typewriter he tried using a word processor.

When that failed, he tried dictation. Michael spent several hours with him one day, writing while Carl spoke. Alas, the results were disappointing. Carl’s speech was just too difficult to understand.

Unable to communicate with others, Carl was left to write stories in his mind, knowing that no one would ever be able to read them. That is perhaps the most frustrating part of all: Those last stories of Carl Jacobi, the ones he could never put on paper, written and rewritten in his mind, honed to perfection over the years, and now totally beyond our reach.

Still, one should not mourn too much for Carl. While we can all regret that he was unable to leave us more than he did, the fact remains that he left us a great deal to remember him by. At the time of his death, five collections of his short fiction had been published. He also left a tremendous body of uncollected fiction, some of which may eventually find their way into new collections.

It can be argued that one never truly dies as long as one can leave a piece of oneself behind. For most people this means children. For the artist, however, it means their art, their creations.

Carl Jacobi was never a big name writer. He never created a “mythos” like Lovecraft. He never published a novel. He never had a bestseller. He never won a major award. In spite of that, Carl Jacobi did have an influence. He was, in fact, the classic “writer’s writer.” Lovecraft marvelled at his versatility. Hugh Cave said of Carl that: “He was saying more in ten words than most writers of the time were saying in fifty, and was doing so by taking the time to find the one word that would hit home.”

Brian Lumley discovered Carl’s work while still a neophyte author. He was so taken with the story “The Aquarium,” that he later paid Carl the compliment of incorporating several of Carl’s fictitious books into one of his own early mythos stories. He also wrote of Carl (in one of the books you may see on the display table): “I consider him one of my teachers, and every horror was a pure pleasure!”

One must also mention Carl’s effect on those of us locally. In 1940, he, Clifford Simak, and a number of fantasy and science fiction fans, formed an organization called the Minneapolis Fantasy Society. That organization lived on until the sixties when it essentially mutated into the group now known as MNSTF — an organization that now hosts one of the largest annual science fiction conventions in the country.

Floor row L to R: Mike Kutz, Richard Tierney. Second row seated L to R: John Koblas,

Carl Jacobi, Eric Carlson. Third Row: Russell Gorton, Robert Borski, Kirby MaCauley,

Donald Sidney-Fryer. Back Row: Joe West, Waring Jones, Steve May. Kirby Macauley

Apartment, Minneapolis, 1970s. Photograph by Eric Carlson.

In the 1970s and 80s Carl was also instrumental in providing support and encouragement for a new generation of horror fiction fans that had sprung up in the Twin Cities area. Writers, artists, and agents like Kirby McCauley, Joe West, Don Herron, Jack Koblas, Eric Carlson, R. Dixon Smith, and Richard L. Tierney — among others — were privileged to call Carl Jacobi their friend. It’s not surprising, under the circumstances, that Carl was prominently featured in Koblas and Carlson’s legendary fanzine Etchings & Odysseys, or that he was selected as a recipient of the Minnesota Fantasy Award in its very first year of existence.

I think I can safely speak for everyone in this room when I say to Carl, wherever he is, “You will be missed, but you will not be forgotten.”

In closing, I’d like to leave you with a brief passage from one of Carl’s own stories, “Tepondicon,” from the collection Portraits in Moonlight:

“It is for you to decide,” she said. “All I can say is that one way leads to the ultimate glory.”

She went out and I stood there in a daze. For five minutes I didn’t move. Glory, she had said. Yes, there would be glory, something which had played no part heretofore in my life. But likewise there would be death. The same death which awaited the doomed citizenry of the seven doomed cities. On the other hand was the Jupiter Stone, embodying all I had fought for.

I walked across to the desk and sat down in the chair beside it. I must put my thoughts and actions of the past days on paper. I must record everything. If I chose the plague door, set up my transmitting set — and finally gained the Jupiter Stone, it would be a condemnation — a curse — to dog me the rest of my days. Honor versus dishonor, balanced against life versus death.

It is this document you are now reading!

At the end of an hour I stood up and neatly folded the paper. The air was hot, stifling. Somewhere a mercury clock pulsed rhythmically. Then, with a little laugh, I strode across the room toward one of the doors. Of course, you all know which door I opened.

D.H. (Dwayne) Olson was a personal friend of Donald Wandrei and has been involved in publishing, editing, and researching the pulp era since 1986. His most important contributions to the field may be found in the various Donald Wandrei (Colossus, Don’t Dream, and Frost) and Howard Wandrei (Time Burial, The Last Pin, and The Eerie Mr. Murphy) collections published by Fedogan and Bremer during the 1990s and 2000s.

I’m reminded of a story by Jorge Luis Borges, “The Secret Miracle,” in which a playwright facing a Nazi firing squad is granted a cessation of time within his mind alone, giving him a year to finish his last play before time resumes and the bullets fly, ensuring that no one else will ever read it.