No More Stories — The Capstone to Joanna Russ’s Alyx Sequence: “The Second Inquisition”

|

|

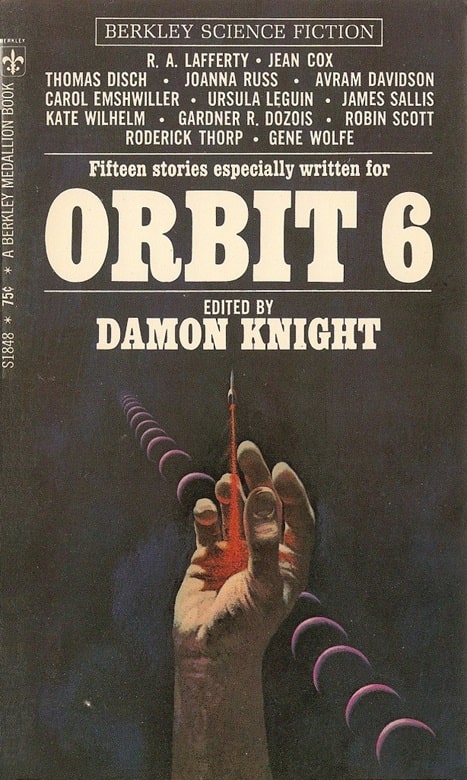

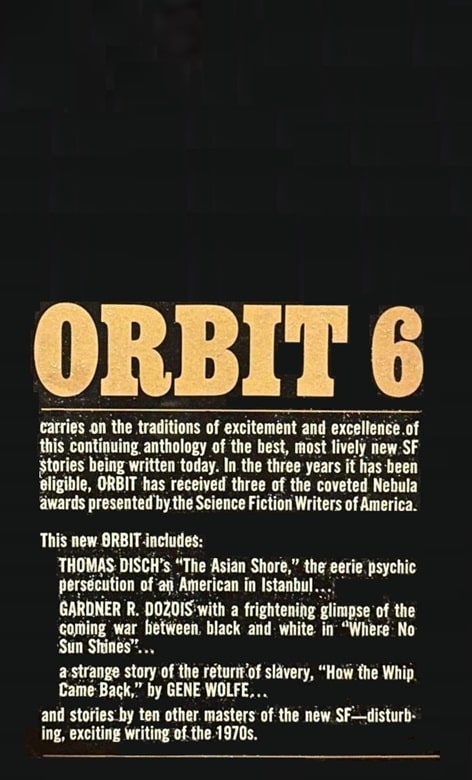

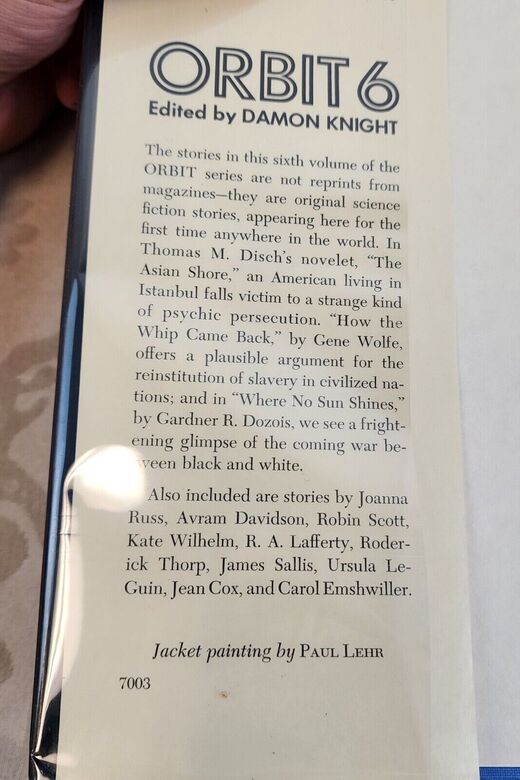

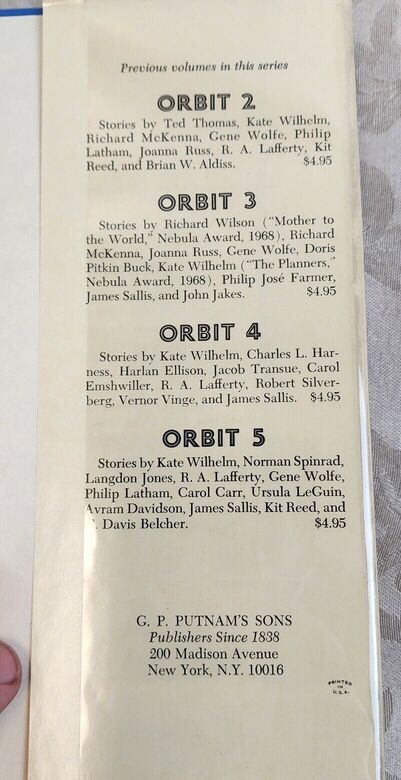

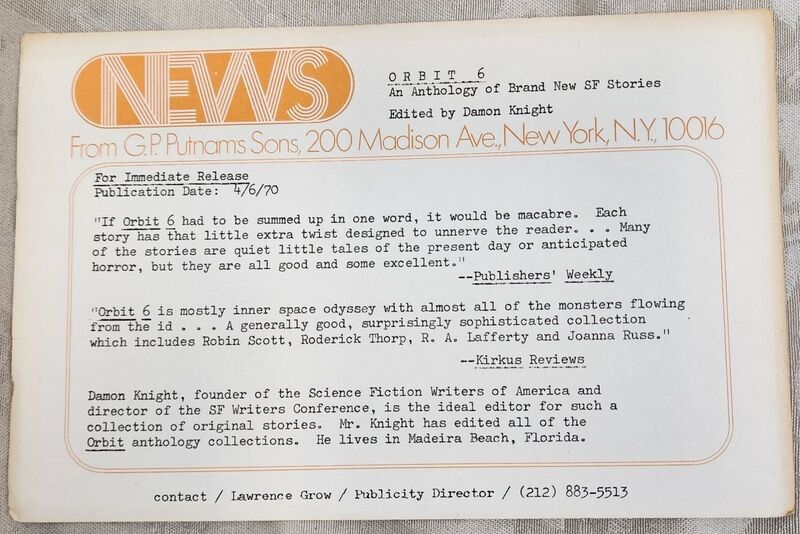

Orbit 6, edited by Damon Knight (Berkley Medallion, June 1970). Cover by Paul Lehr

“No more stories.” So ends Joanna Russ’s great novelette “The Second Inquisition.” But in many ways the story is about stories — about how we use them to define ourselves, protect ourselves, understand ourselves. It’s also, in a curious way, about Joanna Russ’s stories, particularly those about Alyx, a woman rescued from drowning in classical times by the future Trans-Temporal Authority.

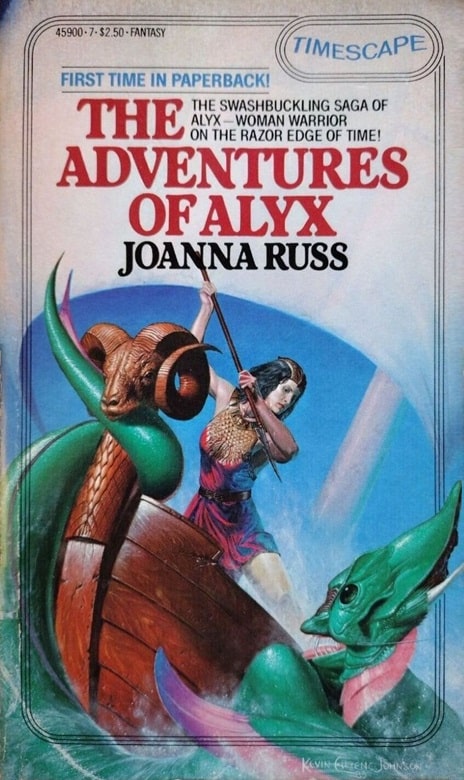

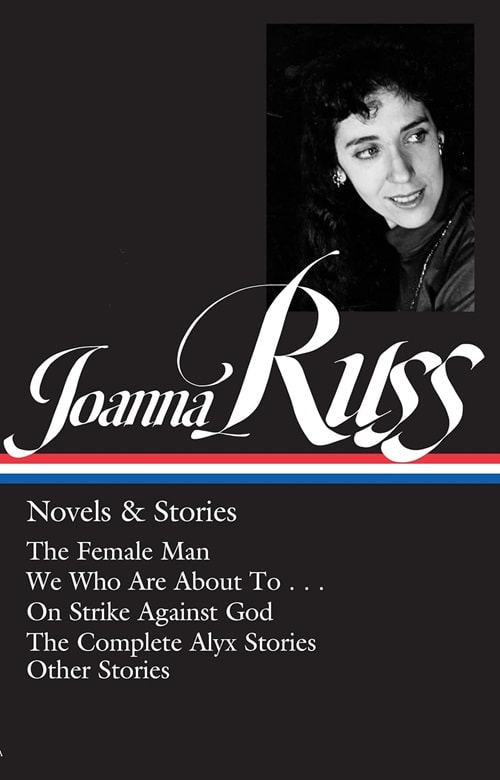

“The Second Inquisition” first appeared in Orbit 6 in 1970. It was nominated for the Nebula Award for Best Novelette. It was included in the anthology Nebula Award Stories 6, along with Gene Wolfe’s “The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories,” which first appeared in Orbit 7 and was also nominated for a Nebula — and which has some resonances with “The Second Inquisition.” Russ’s story has been anthologized several times since, and is collected in her book The Adventures of Alyx, and in the recently released Library of America collection Joanna Russ: Novels and Stories.

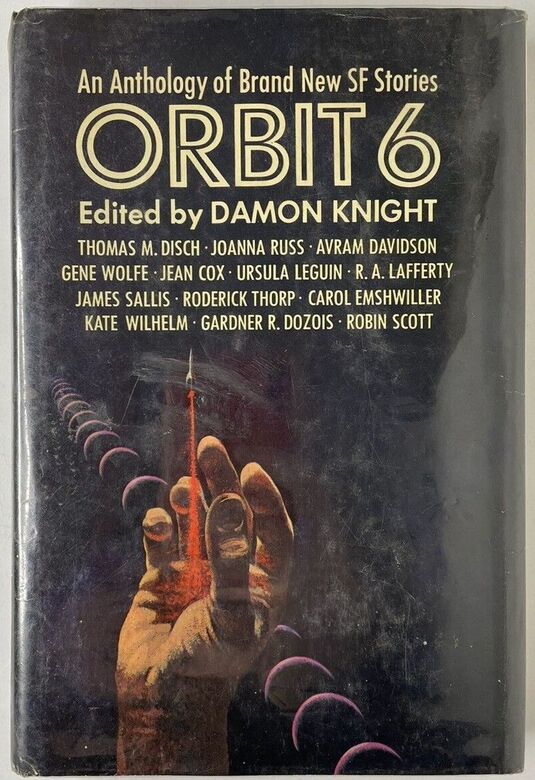

[Click the images if you’re inquisitive about larger versions.]

Joanna Russ: Novels & Stories (Library of America, October 3, 2023)

First, the epigraph, from John Jay Chapman (a direct descendant of the first Chief Justice of the US):

If a man can resist the influences of his townsfolk, if he can cut free from the tyranny of neighborhood gossip, the world has no terrors for him; there is no second inquisition.

Let’s hold that thought.

The story opens with the narrator — a 16-year old girl in 1925 — telling about their visitor, or boarder. “I often watched our visitor reading in the living room … brownish, coppery features so marked that she seemed to be a kind of freak … the gracefulness of a stork … legs like a spider’s, with long swinging arms and a little body in the middle … at close view she looked as if every race in the world had been mixed and only the worst of each kept …” She is 6′ 4″, with short, coarse, hair. The narrator’s father doesn’t like tall women or short hair, and hardly anyone in their town knows what to think about “colored people.”

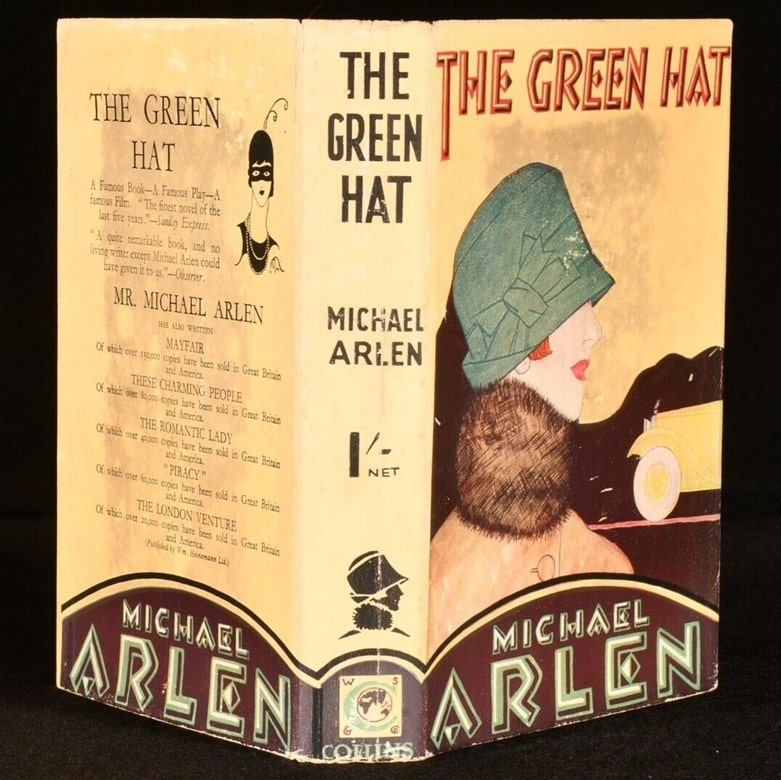

The Green Hat by Michael Arlen

The visitor is reading The Green Hat (a scandalous bestseller by Michael Arlen1) — “This a very bad book,” she says. And inevitably she gives it to the narrator to read, which she does, to her parents’ horror. The mysterious visitor continues to fascinate the narrator, and to bother the father and (maybe?) mother. There is a beautiful scene describing a conversation between the narrator and the visitor on the subject of Wells’ The Time Machine — with a question — is the visitor an Eloi or a Morlock? “I am a Morlock… There are half a thousand Morlocks and we rule the worlds.”

The hinge scenes are at a dance at the Country Club. Not just the rich families but the “nice” people are invited — including the narrator’s family. She gets to go (despite her father’s apparent reluctance) and she and the visitor accompany a friend (and the friend’s father.) The visitor makes a splash of course — and the narrator’s description of her is different than before:

Then she moved and I thought she was beautiful, all black and rippling silver like a Paris dress or better still a New York dress, with a silver band about her forehead like an Indian princess’s…

Then this story becomes explicitly SF, as a man resembling the visitor is at the party, and insists on seeing her.

This leads to a violent confrontation back at the narrator’s house — with the visitor’s “cousin” left dead. There is a curious interlude, with the visitor ready to leave but not leaving yet, taking up with a Polish immigrant named Bogalusa Joe for a while, then declaring it’s time for her to leave.

And shortly thereafter there is an invasion of sorts — of Morlocks, and a battle, ambiguous as to motivation and perhaps result, but with the visitor killing a seal-like alien and losing an eye in the process. And soon she is gone — except for one final conversation when she appears in the narrator’s mirror. And the final paragraphs:

Nothing came. Nothing good, nothing bad. I heard the lawnmower going on. I would have to face by myself my father’s red face, his heart disease, his nasty insistencies. I would have to face my mother’s sick smile, looking up from the flower-bed she was weeding, always on her knees somehow, saying before she was ever asked, ‘Oh the poor woman. Oh the poor woman.’

And quite alone.

No more stories.

That’s a straight reading of the text. But Joanna Russ is a subtle writer. There is a lot more going on. Another reading of the story — the most common one, I think — is that everything about “the visitor” is in the narrator’s imagination. This reading is reinforced by one of the most powerful passages — the one in which the narrator comes into the visitor’s room and talks to her, about college, about The Time Machine, about Morlocks.

|

|

Orbit 6, hardcover edition ( G. P. Putnam’s Sons, March 1970). Cover by Paul Lehr

But that scene is clearly presented as an imagined conversation:

‘You look eighteen,’ she would say. … ‘I did something funny once,’ I would go on.

Second conditional tense throughout, so a clear indication that the narrator is imagining the visitor’s conversation — at least in this instance. With some crucial paragraphs:

You are exactly right. I am a Morlock. I am a Morlock on vacation. I have come from the last Morlock meeting, which is held out between the stars in a big goldfish bowl, so all the Morlocks have to cling to the inside walls like a flock of black bats … There are half a thousand Morlocks and we rule the worlds…

And:

Then I would say, ‘Can I come with you?’ leaning against the door.

‘Without you,’ she would say gravely, ‘all is lost,’ and taking out from the wardrobe a black dress glittering with stars and a pair of silver sandals with high heels, she would say, ‘These are yours. They were my great-grandmother’s, who founded the Order. In the name of Trans-Temporal Military Authority.’ And I would put them on.

It was almost a pity she was not really there.

If this exchange is only in the narrator’s imagination, then it is plausible that the visitor is entirely her invention.

So — the narrator read The Green Hat on her own. (We know her mother read it.) The narrator went to the dance and left early because — she was humiliated? She was bored? She drank too much punch? The other Trans-Temp agents — or Morlocks — are likewise just imagined, as of course is the final scene with the visitor appearing in the mirror. The trickiest part is the visitor’s affair, with Bogalusa Joe. I had a thought there — did the narrator’s mother have that affair?

Is the narrator, then, Joanna Russ herself, imagining the Alyx stories she would later write? I have no doubt that there are autobiographical elements to the depiction of the narrator, but it doesn’t quite match — most simply, Joanna Russ was born 12 years after the action in “The Second Inquisition.” Nonetheless, many of the narrator’s desires may track with those of the author at the same age, and perhaps her family situation also has parallels (I don’t know.)

|

|

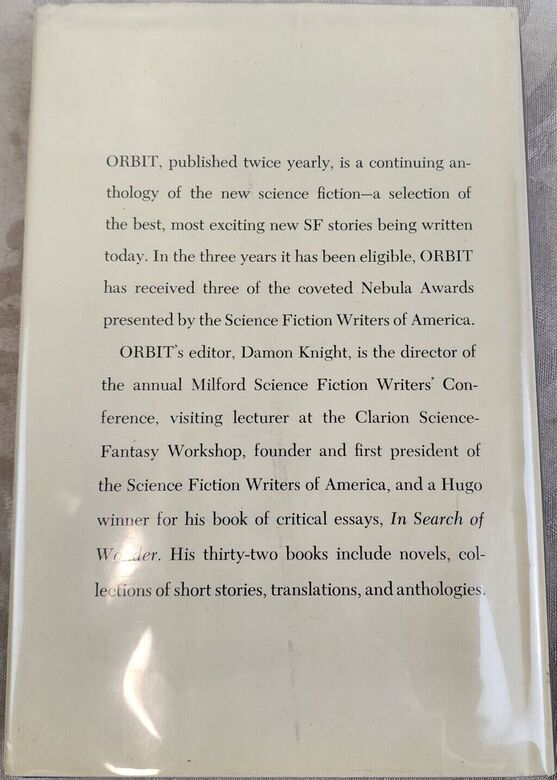

Cover flaps for Orbit 6

What does the story mean, then, in this reading? (Keeping in mind that most great stories mean many things.) It seems a cry against the stultifying atmosphere of small towns, or of any small community, at one level. And a portrayal of the place of women in America in the ’20s — and the ’40s — and still the ’60s. And the way many men mistreated their wives. The narrator’s mother is a crucial character. Her fear of her husband. Her defense of him against justified criticism. Her cries of “Oh the poor woman!” — when surely “the poor woman” is herself. (And note the line from the closing: “always on her knees somehow.” That depiction of submission is damning and deeply sad.)

She does have small rebellions, like reading The Green Hat (a story of a woman who sleeps around, who defies her father, who tries to break up her lover’s marriage — and a story featuring venereal disease as a major plot point, and a conclusion that looks a lot like suicide.)

And bigger rebellions — letting her daughter attend the dance; or, still more significantly, if my reading is correct, having an affair with a Polish immigrant (who himself has previously had a black lover.)

And what does the narrator do, as a girl? She reads transgressively as well. And she dreams, she makes stories, of a future ruled by Morlocks, of a future of mixed-race people who rule the Galaxy, of a future in which tall women fight and scheme — for justice or maybe just for power. The visitor, then is her dream of what she wants to be: powerful, in control, a leader, a fighter. (And if not “pretty” definitely alluring.)

Putnam publicity release for Orbit 6

At the end, the declaration: no more stories. Is she giving up? Or is she resolving that instead of making up stories, she will try to make her stories real? There is an awful lot of “neighborhood gossip” in the town the narrator grows up in. Perhaps she is ready to set herself free from it – from those kind of stories – and so free herself from the second inquisition. Or, perhaps, she is writing stories – these stories of Alyx – and now there are no more.

But, hey, I’m a science fiction reader! (And Joanna Russ was a science fiction writer!) I like to believe in the things the narrator may have imagined! And that’s cool too. That’s a future with time travel. That’s a future with humans spreading out among the stars — and with intelligent aliens as well. That’s a future in which a strong woman from Ancient Greece can become a power in an organization that fights for justice in a star-spanning polity.

That’s also a future with petty politics and violent disagreements between the people of what seems to be an agency we root for, a future with silly rich people getting themselves in trouble as clueless tourists, a future with as much injustice as we see on Earth today, it seems. Perhaps that’s not what’s really happening in “The Second Inquisition,” but I often like to think it is!

And now a diversion – the last line in “The Second Inquisition” is “No more stories.” But of course there were more stories, and even more stories about stories. And one of those – another of Russ’s very best stories, I think – is “My Boat.” Does this story resonate with “The Second Inquisition”? I think it does.

|

|

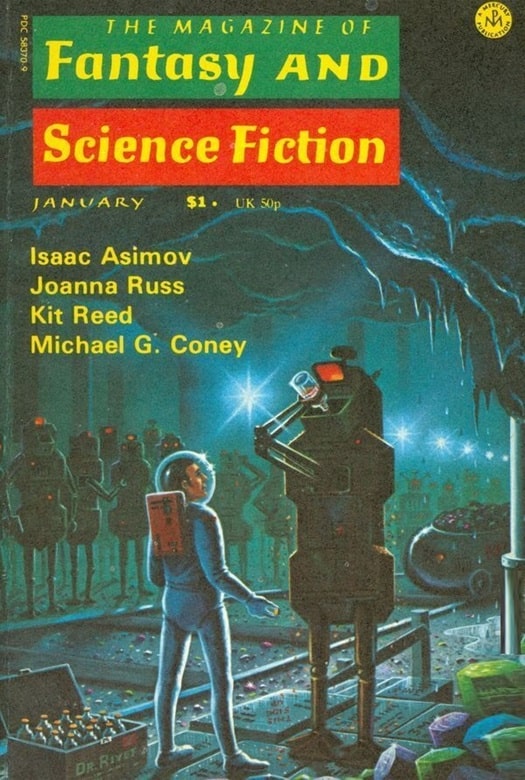

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, January 1976, containing “My Boat.” Cover by David A. Hardy

“My Boat” appeared in F&SF, January 1976, and was collected in The Zanzibar Cat2. It’s been well-anthologized, including in the Wollheim/Saha Year’s Best. It’s the story of a black girl named Cissie Jackson, whose father was killed by a white policeman, and whose mother is strict and religious. Cissie is pathologically shy, and also brilliant, and a talented actress. And we see her entirely through the eyes of our narrator, Jim, who is telling her story to his agent. (He’s a television writer.)

Already we see the framing – this is a story within a story, and there are more stories within. Jim and his nerdy friend Alan are both in the theater group in their newly integrated high school. It’s 1952. And they end up half adopting Cissie, once they recognize her talent. They’re also motivated a bit by their 1950s “enlightened” attitudes that Jim ruefully acknowledges made him just another “white liberal racist.”

Nerdy Al is deeply into fantasy, and he bonds closely with Cissie, who is her own kind of nerd, and Al tells her about places like Ooth-Nargai and Celephais the Fair and Kadath in the Cold Waste. Cissie is interested in history, places like Knossos and Benin – and Atlantis. People like the Queen of Saba and Nofretari. (Not “Sheba” and “Nefertiti.”) Jim is obviously kind of a third wheel, but one day Cissie and Alan invite him to come boating.

The boat – which Cissie calls My Boat — is a leaky old rowboat. But Jim is willing to play along. And when he gets on the boat, things start to seem different. The crudely painted lettering My Boat is inlaid in brass or gold. The boat begins to seem bigger. There’s a nice cabin in the center, with a galley and beds. And it’s not a rowboat – it’s a yacht. More than that, Cissie and Alan have themselves transformed: Alan to some sort of avatar of Francis Drake, and Cissie to a beautiful woman, some sort of African queen … And they are ready to travel – to Ulthar, or Thalarion, or even Atlantis – and the Atlanteans have promised to give Cissie the secret of making My Boat a starship…

Jim gets cold feet. It is all too strange for him. Also, he says, “I guess I didn’t feel good enough to go.” And, “I didn’t want that knowledge… I didn’t want to go that deep. It was the kind of thing most seventeen-year-olds don’t learn for years: Beauty. Despair. Mortality. Compassion. Pain.”

And he leaves Cissie and Alan to go – and they don’t return. Jim has to try to convince Cissie’s mother that “Alan Coppolino, boy rapist, hadn’t carried her daughter off to some lonely place and murdered her.” He has to go to “The-College-of-My-Choice” and become a TV writer and live his ordinary life. And a couple of decades later here he is pitching this crazy thing that happened to him as a teenager to his agent as the basis for a movie or a series. And of course his agent says, sure, that’s cool, but we have to make the girl a Martian, and blond, and rich, and there has to be lots of sex…

What does this have to do with “The Second Inquisition”? Well… as I read it, Cissie’s dreams of escape – her reality of escape, in the story – are analogous to the narrator’s stories of the Trans-Temporal Military Authority. In “The Second Inquisition” the narrator is facing the constraints of conventional 1920s life, and an abusive father and a timid mother, and she “escapes” to her thrilling dreams of a future in which women are tall and strong and powerful and humans are spread across the galaxy, not confined to one planet – or one small town.

In “My Boat,” Cissie is facing racial prejudice (and a murdered father as a result) and a loving but very strict mother, and a milieu in which the Civil Rights movement is only just getting any sort of momentum. (Jim says at one point “And maybe if the civil rights movement had started a few years earlier — ”) And she escapes to thrilling dreams of glorious lands like Atlantis and historical Benin and Crete and Saba – not to mention the wondrous places her friend Alan is obsessed with, Kadath and Nir and so on. Plus the stars.

I’ve elided the concluding pages of “My Boat” above. Point of view is critical, of course, and “The Second Inquisition” is from the narrator’s point of view, but “My Boat” is not from Cissie’s POV, but from Jim’s. Jim has a chance to see Alan again – still looking about seventeen – he needs Jim to help him find his copy of the Necronomicon (from a long-demolished apartment that is magically still there.) So when Jim realizes that his story – Cissie’s story – still has no place in the world, even as a TV movie, he may be ready to dream like they do. And perhaps Jim remembers something Cissie told him: “For you, Mister Jim, let me tell you: the main thing is belief!”

|

|

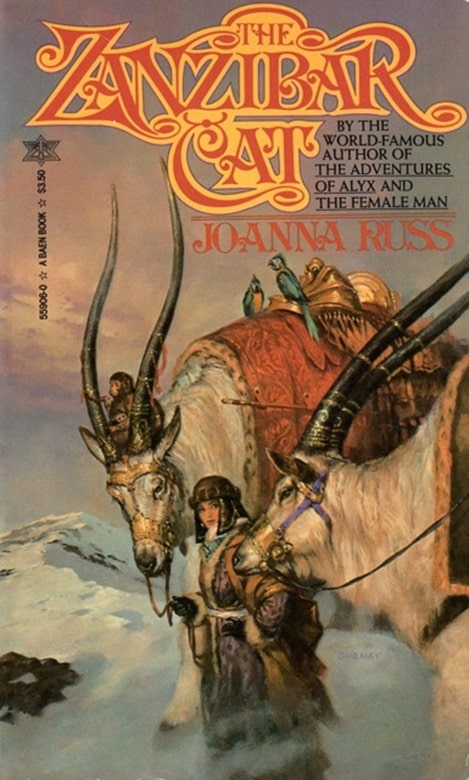

The Zanzibar Cat (Baen, September 1984). Cover by James Gurney

Curiously, then, the main characters’ decisions in the two stories are different: in “The Second Inquisition” the choice (or the fate) is “no more stories,” while in “My Boat” Cissie and Alan escape to stories. (Russ does call “My Boat,” in a brief introductory note in The Zanzibar Cat, “A shameless example of what happens when you unite memories of Cicely Tyson (the best actress in the world), a nice Lovecraft nut I know, and sheer wishful thinking.”)

Does this mean that the narrator in “The Second Inquisition” realizes that she has no choice but to abandon stories? Or that she doesn’t have enough “belief”? And does it mean that Cissie and Alan have made the happiest choice – the “wishful thinking” choice – to live forever in the land of Story? And who is right?

Back to the main thread.

A few more random notes. Many readers take the visitor to be Alyx’s great-granddaughter – based on the line “They were my great-grandmother’s, who founded the Order.” But did Alyx found the Order? I’m not sure that’s been established – after all, she was rescued by Trans-Temp from ancient Greece. The “Order” is clearly related to the Trans-Temporal Military Authority, but how? A splinter group? A special cadre? And the visitor seems at odds with the Order as well. Looked at another way, the context of that line – the narrator receiving those shoes from the visitor, may suggest that the narrator herself is the visitor’s great-grandmother, receiving the shoes in a sort of time loop.

The visitor, to be sure, does share a mannerism with Alyx – casually calling people “baby.” And as Jim Janney points out in the comments that towards the end of Picnic on Paradise it is revealed that Alyx will be teaching her “special and peculiar skills in a special and peculiar little school” – and that perhaps that school will become the Order — especially as Alyx notes that her skills might not be detachable from her “special and peculiar attitudes.”

|

|

The Adventures of Alyx (Timescape/Pocket Books, August 1983). Cover by Kevin Eugene Johnson

All the other Alyx stories — including the later “A Game of Vlet,” which is not included in The Adventures of Alyx — end with the line “But that’s another story.” Which makes the ending of “The Second Inquisition” — “No more stories.” — even more resonant.

A trivial point — but the central character in The Green Hat — the wearer of the green hat — is named Iris Storm, and so is a major character in Picnic on Paradise named Iris. Probably sheer coincidence, though there is a storm in Picnic on Paradise, too.

I think “The Second Inquisition” is one of the great stories in SF history, and multiple rereads only reinforce my view. It has multiple sides. One side is a completely honest and believable character portrayal of a teenage girl in a small town in the 1920s, trying to find a way to be herself, and not what her parents, and society, seem to want her to be. Another is a thrilling story of time travelers and galaxy spanners engaged in a struggle for the fate of the stars. Both are told cleverly, and wittily, and movingly. There is compelling action, and smart conversation. And the resolution is profoundly affecting.

Joanna Russ is one of the great writers in SF history — and a very important critic. She was as passionate, as involved, a writer as one can imagine — and also consistently witty, funny — though the wit, the jokes, have very sharp edges indeed. She wrote exceptional prose as well, in a non-showy fashion. Severe health problems curtailed her productivity after the mid-80s — only one short story after 1984, though she did produce some significant nonfiction. She died in 2011, aged 74. She was clearly worthy of being named an SFWA Grand Master, and I’m not sure why she wasn’t, though I suppose the lack of fiction in the last quarter century of her life is part of the reason.

1For those who aren’t familiar with The Green Hat, I have reviewed it here.

2My review of The Zanzibar Cat is here.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was an obituary for D.G. Compton by Robert Chilson. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over 200 articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

[…] […]

I had no idea The Green Hat was an actual book. The idea that Alyx founded the Order is suggested by the final paragraphs of Picnic on Paradise and the special school she is expected to run, but Russ is far too subtle to say anything like that directly.

I always have the feeling, when reading stories like this one or the Wolfe, that the author is somewhere in the background jumping up and down in frustration at my inability to pick up on obvious hints.

Thanks! — that bit at the end of Picnic on Paradise is suggestive — especially the part about her special skills not being detachable from her special attitudes! I had not picked up on that! I’ll revised the article and mention that (with credit to you.)