Weird of Oz on the Art of Rating 2 (of 3)

Last week, I began my reflections on the art of rating. These thoughts are based on my own 25+ years of reviewing literature and film, as well as on being an avid reader of reviews and follower of particular critics.

To recap, in last week’s post I covered the selection of a ratings scale, which can vary from the most simple “thumbs up/thumbs down” to a more nuanced 10-point scale such as I use (five stars, with half-star increments). I also touched on the implications of being either a stingy or a generous rater.

This week, I’ll delve a bit deeper by considering the importance of establishing one’s viewpoint and communicating that viewpoint (with all its preferences and prejudices) to the reader.

After I see a film, there are two additional pay-offs besides the film-viewing experience itself: 1) (social) discussing the film with friends, family, colleagues who also saw it; and 2) (solitary) paying a visit to rottentomatoes.com, the aggregating site that links to hundreds of reviewers, to find out what amateur and professional critics thought of it. It’s fun to see how one’s own impression compares to the general consensus, and I enjoy those “A-ha!” moments when a critic deftly articulates some emotional or intellectual response the film also evoked in me (or when they wittily trash an aspect of the film that I also abhorred). Doesn’t always happen, even when a critic has assigned to a film the same rating I’ve given it. It goes without saying that we can like the same thing for different reasons; likewise, we can dislike something equally vehemently, but on completely different grounds.

III Where Are You Coming From?

This leads me into my third general observation: It is important for a reviewer to convey the reasons why he/she likes or dislikes something. Any Beavis or Butt-head can say “That sucks” or “That’s cool;” it takes some higher functioning brainpower to elaborate on why — and, consequently, to provide the reader with some useful indication of whether he/she might also enjoy the work or wish to avoid it.

This goes beyond just discussing a work’s merits and failures in a sort of structuralist vacuum; newer schools of critical thought have for some time recognized that no critic is completely objective: we all bring our own personal preferences and prejudices. Reader-response and various schools of political and psychological criticism astutely recognize that a person’s reaction to a particular text reveals as much about the person as about the text.

Thus informed, I fall very much into the Roger Ebert camp of film criticism. Like Ebert, I am not averse to sharing personal anecdotes if they will help illuminate why I reacted to a work the way I did. For readers, especially readers who follow a critic from week to week, knowing something about the critic’s tastes and biases can help them contextualize the critic’s response to the work in question.

Of course, this means readers will have a better idea of when your opinion should be taken with a grain of salt. If they know you have a deep-seated aversion to romantic comedies, they may read your review of the latest Jennifer Aniston vehicle not so much to get a balanced review as to see how you are going to skewer it this time. Likewise, they might deduce that you have a soft spot for superhero movies, and are therefore more likely to be forgiving of one that is merely mediocre. Best to be clear about these tastes and genre preferences up front — if they know you are partial to the superhero genre because you grew up reading Marvel and DC comics, they’ll be able to trust the historical background you can provide. At the same time, they’ll be able to factor in some counterweight to your tendency to be more sympathetic to such films.

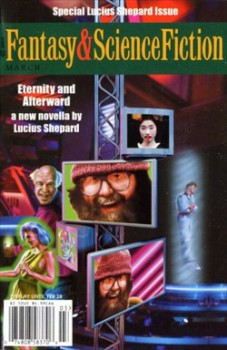

For example, Lucius Shepard regularly reviews films for The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Now, I think Shepard is one of the best short-story and novella writers in the speculative-fiction field today. Voodoo, zombies, ghosts — in his able hands such things seem all too plausible and real. But Shepard has a chip on his shoulder against superhero movies. If it’s based on a superhero comic book, he has already pretty much dismissed it out of hand. So I know this going in if I check out his review of the latest Iron Man or Spider-Man flick. He makes no bones about it; he is willfully condescending toward the whole genre. Obviously, I often disagree with him — but I know where he’s coming from, so I am not taken by surprise when he lambasts Spider-Man 2. Rather, I find it noteworthy that he actually liked Batman Begins.

For example, Lucius Shepard regularly reviews films for The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. Now, I think Shepard is one of the best short-story and novella writers in the speculative-fiction field today. Voodoo, zombies, ghosts — in his able hands such things seem all too plausible and real. But Shepard has a chip on his shoulder against superhero movies. If it’s based on a superhero comic book, he has already pretty much dismissed it out of hand. So I know this going in if I check out his review of the latest Iron Man or Spider-Man flick. He makes no bones about it; he is willfully condescending toward the whole genre. Obviously, I often disagree with him — but I know where he’s coming from, so I am not taken by surprise when he lambasts Spider-Man 2. Rather, I find it noteworthy that he actually liked Batman Begins.

With the best reviewers, you start to feel like you know them, or at least know something about their frame of reference. When I watch a new film, I sometimes find myself thinking, “I wonder what Ebert would think of it?” (Too bad that’s a question that can no longer be answered.) Or “What did Ty Burr (of the Boston Globe) make of that crazy mess?” Ebert and Burr have been regular go-tos for me, not just because they are knowledgeable cinephiles, but also because they do not harbor the bias against genre one finds in so many other “smart” publications like The New Yorker (their reviewer was one of the few to trash Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man [2001], because, of course, it was about a guy who was bitten by a spider and then dressed up like a spider to fight crime and isn’t that just so silly, don’t you know? It was beneath their contempt, truly).

Ebert was and Burr is conversant with the pulp roots of so much sci-fi and fantasy, giving them a better context to assess (and appreciate, even celebrate) a new Star Trek or John Carter film. Even when you disagree with them (as I sometimes do), you know where they’re coming from — you can see their point, and they know what they’re talking about (even if they’re not always right).

When it’s all said and done, it comes down to personal taste, anyway, so finding a critic whose taste, in general, parallels one’s own is what a potential filmgoer or book buyer primarily wants. Consequently, a conscientious critic will be forthcoming about preference for a certain type of film or prejudice against another type. Look, if I’m going to a food critic to find a recommendation for an Italian restaurant, I appreciate if the critic makes it clear that he generally has no taste for Italian food. Maybe he should stick to reviewing other cuisines.

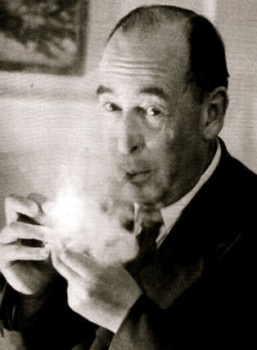

C.S. Lewis made this same point over fifty years ago, observing that some people have a strong prejudice against imaginative literature in toto, finding anything that smacks of fantasy or science fiction distasteful. He suggested that critics harboring such a bias had probably best recuse themselves from reviewing works of fantasy and science fiction, noting that their thoughts on the latest work by Arthur C. Clarke or Isaac Asimov would be relatively useless to any spec-fic reader who wanted to know more about the book and how it compares to earlier works in the genre.

I’ll save my fourth point, which gets to the heart of how one compares films, for a third and final part next week (like Peter Jackson, I decided to stretch this out to three installments! This will allow more character development for any dwarves that appear in these posts, and maybe the introduction of a surprise elf or two). Preview: Stephen King and Roger Ebert will weigh in on rating standards. I’ll raise the question of whether Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure should be judged in comparison to 2001: A Space Odyssey, or whether that would be comparing apples and oranges. And if a reviewer gives his/her highest rating to both Casablanca and The Avengers, does that mean he/she considers The Avengers to be a classic on par with Casablanca?

That about wraps it up for now. Be back next week for the conclusion of my thoughts on rating. The final chapter promises bigger stars and more explosions!

Good, thoughtful posts on the subject. Look forward to reading the end of your trilogy!

Two thumbs up!

Glad to have you along for the ride, mcglothlin. And now that the trilogy has concluded with today’s post, I hope you’ll weigh in on the final installment!

And thanks, clwhitfill! Careful, though, about using those thumbs–Ebert did trademark the “two thumbs up” designation. 🙂

[…] Weird of Oz on the Art of Rating 2 of 3 […]