Set in Stone: N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season

|

|

The Fifth Season (Orbit, 2015). Cover by Lauren Panepinto

So, there I was, strolling through the endless corridors of Black Gate’s Indiana compound, when I chanced upon a book shelf I hadn’t noticed before. Over it hung a sign, carved in blasted stone, reading, The Fifth Season. I picked up the lone book on the shelf, toted it home, and read, with increasing awe, one of the finest science fiction novels of my adult life.

Strike that. The Fifth Season is one of the finest novels I have read, period.

Maybe that’s why it won the 2016 Hugo Award.

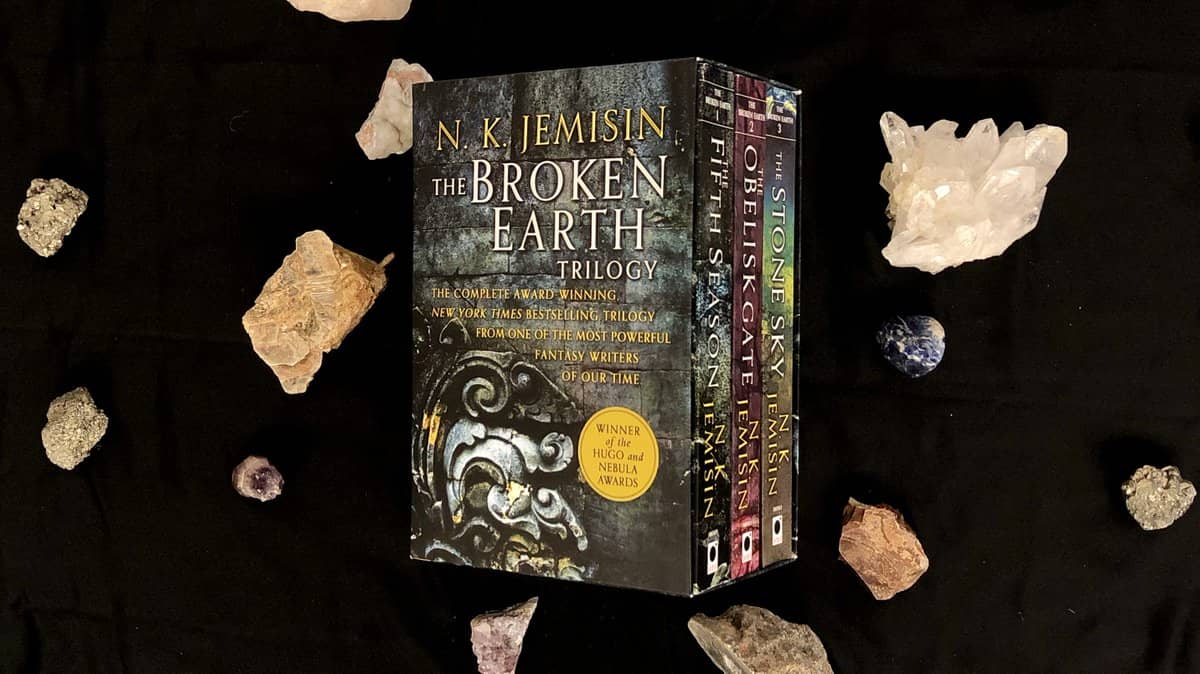

Oh, and did I mention? The Fifth Season is book one of N.K. Jemisin’s The Broken Earth trilogy, and each of the other titles in the series also won the Hugo Award! And if that still isn’t enough to grab your attention, the third title, The Stone Sky, also made off with the Locus and Nebula Awards.

The Fifth Season opens with a prologue entitled, “you are here.” Its first sentence: “Let’s start with the end of the world, why don’t we?”

Now, my all-time favorite opening line in fiction comes from L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between, which begins with, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” The Fifth Season also has its jaunty, deeply heartfelt eye fixed firmly on the past, and on all that has gone wrong to make the world –– the book’s world, and ours –– as muddle-headed and broken as it is. It becomes the business of The Fifth Season and its exceptional characters to bring us up to the present, and to right as many wrongs as possible along the way, no matter the cost.

To explain any of this without dropping unforgivable spoilers (crumbs from the table of plenty) is challenging, thanks in part to the novel’s structural trick of running through three different time periods in alternating triads of chapters. Usually, such devices leave me cold; they suggest that the author doesn’t have full confidence in the story at hand, or worse, doesn’t understand what they’re doing. The gimmickry becomes window dressing to cover whatever vacuity fills the novel’s center.

N.K. Jemisin. Photo © John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

No such worries here. Readers of The Fifth Season quickly realize that they are in the hands of a master story-teller, one capable of keeping an exceptional number of balls in the air. (More, even, than Donald Barthelme’s father in “Views of My Father Weeping.”) While the prologue demands special attention from the reader (much like the crowded party, stuffed with strangers, that opens War and Peace), everything settles quickly into place from there on, and the pages all but turn themselves.

The opening chapters introduce us to three exceptional women, at very different stages of their lives. Damaya is a child and budding orogene, meaning she can employ the latent power stored in stone to alter the world around her, but orogenes are revered and reviled in equal measure. In Damaya’s world, one especially prone to seismic activity, orogenes keep civilization from coming apart at the seams, but if they’re left feral and untrained, they’re apt to kill everything in a one-mile radius if they so much as lose their temper.

And so Damaya, once the curse of orogeny is discovered within her, gets swept away for schooling at the Fulcrum. No cheerful Hogwarts, this. The Fulcrum is a boot camp where young spirits are broken in the service of a supposed greater good.

We also meet Essun, mother of two, and an orogene in hiding. She is protective, bitter, and private; how she reached the outlying town she now calls home is a mystery. Her neighbors have no idea of her power. What Essun knows for certain is that her husband, Jija, has finally realized that their two children are also nascent orogenes. Upon discovering this, Jija kills the boy and flees with the girl. Essun sets off in pursuit.

Which brings us to Syenite, a young woman working her way up the Fulcrum ladder. Her current, career-advancing assignment is to accompany a master orogene as he clears a seaside shipping port of excess coral, but there’s a catch: she’s also ordered to conceive the man’s child, a task that mentor and mentee find equally, comically distasteful.

Without ever sacrificing the immediacy of the story-telling, Jemisin makes the claim that the fault lines in society become its destiny. The “stills” who lack orogenic power, but who make up the bulk of the population, rarely hide their antipathy toward those who do. They call orogenes “rogga,” and the double g in that invented slur is no accident. The old and new hatreds of Jemisin’s imagined world mirror our own all too well.

But Jemisin, through Syenite, in particular, is not content to simply portray the casual and corrosive racism of this orogenic-dependent world. No one and nothing in this book is passive. Instead, her characters grapple directly with the deeper, more vicious quandary of whether a society that depends on a strict caste system must, as a consequence of its own rot, be violently overthrown, no matter how many “innocent” lives may be lost in that toppling.

But then, who in such a world is really innocent?

What battles erupt are vivid and appalling. People we care about perish unexpectedly, including those who (we like to think) deserve better. The “magic” of orogeny remains grounded throughout, albeit with some artistic license, abiding by the laws of conservation of mass and energy –– always a plus.

Book Two, The Obelisk Gate, beckons. I cannot wait to begin. As for N.K. Jemisin, she was awarded a MacArthur Genius Grant in 2020, and continues actively writing. In 2021, Time listed her as one of the world’s top hundred most influential people.

Onward.

Mark Rigney has published multiple pieces for Black Gate, including the perennially popular “Youth In a Box” and several stories in the Black Gate Online Fiction library, including ”The Trade,” “The Find,” and “The Keystone.” Tangent called the tales “Reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. I highly recommend the complete trilogy.”

Away from Black Gate, he is the author of the supernatural quartet, The Skates, Sleeping Bear, Check-Out Time, and Bonesy, all of which are now out of print, thanks to the demise of Samhain Publishing. (He is STILL working to correct this injustice as fast as humanly possible.) New stories will shortly appear in Tales from the Magician’s Skull and Wyldblood. Previous work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in Lightspeed, Unlikely Story, Betwixt, Black Static, The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review, Realms of Fantasy, Witness, The Beloit Fiction Journal, Talebones, Not One Of Us, Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet and many more. His website is markrigney.net.

I just picked up this trilogy at Christmastime, and can’t wait to dig in to it.

This was a distant second in my 2016 Hugo voting (to Naomi Novik’s Uprooted). I loved the journeyman sections, liked the apprentice sections, and hated the “you” sections.