Pushing Us Away from Gender-Based Assumptions: “Winter’s King” by Ursula K. Le Guin

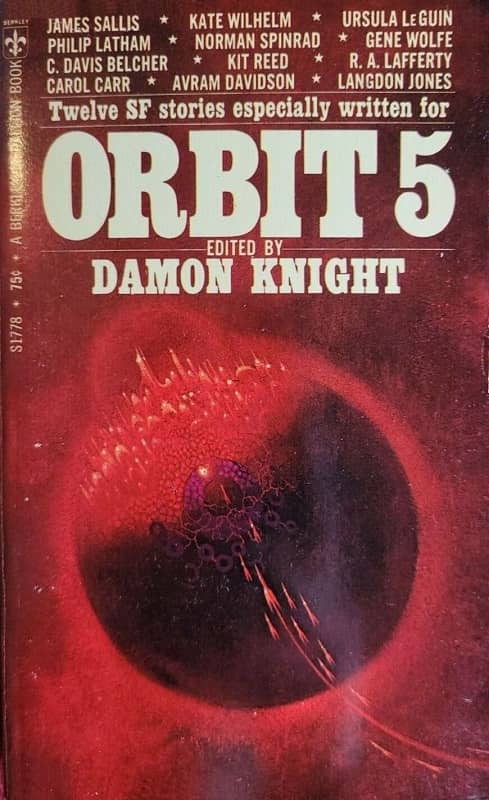

The Wind’s Twelve Quarters (Harper & Row, 1975). Cover by Patricia Voehl

After a bit of a hiatus, I’m returning to my series of essays about stories I find particularly interesting – often because of how good they are, but sometimes for other reasons. My goal is to examine them closely, and to try to understand – at least a bit – why they work, or why they don’t, or at least why they are interesting.

Ursula Le Guin is a favorite writer of mine. That’s hardly a challenging stance to take! I love many of her novels: The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed of course, and the Earthsea books, but also her last novel, Lavinia, and the YA novels that preceded it, collectively called Annals of the Western Shore; and her first completed novel (published much later): Malafrena. And too I love her short fiction, above all I’d say “Nine Lives” and “The Stars Below”. Another short story – or novelette – that has long been a particular favorite of mine is “Winter’s King.”

I first read “Winter’s King” in her collection The Wind’s Twelve Quarters (a collection I chose long ago as the best single author collection of SF of all time (not counting “Best of” collections, or “Collected Stories”).) (Since that time I’d allow Stories of Your Life, and Others, by Ted Chiang, as another contender.) But, intriguingly, Le Guin’s introduction to that story in her collection mentions that it is revised from its original version in one important way: the gender of the characters from the primary planet of that story, Winter, is represented as female in the new version, but in the original version they were depicted as both male and female.

[Click the images for winter-sized versions.]

|

|

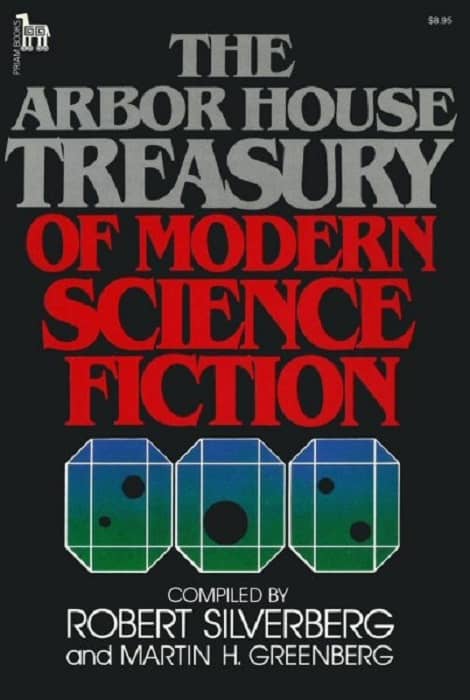

The Arbor House Treasury of Modern Science Fiction (Priam Books/Arbor House, April 1980)

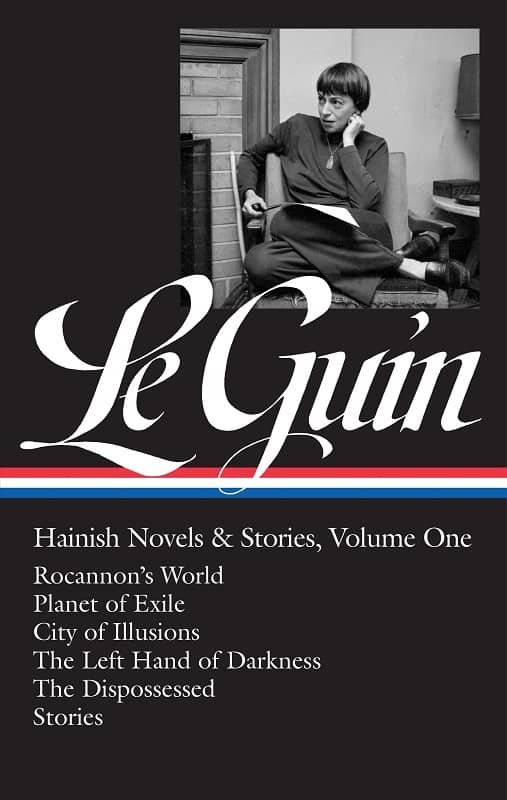

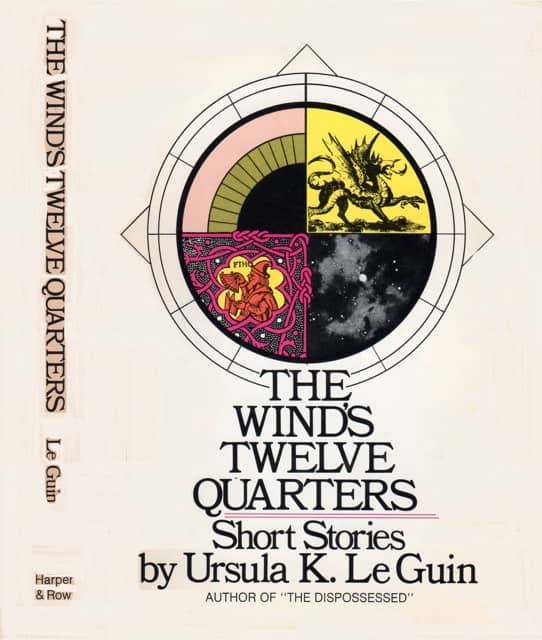

The story has been reprinted several times since, most notably in The Arbor House Treasury of Modern Science Fiction, edited by Robert Silverberg and Martin H. Greenberg; and as part of the Library of America’s volumes of Le Guin’s fiction, in the volume called Hainish Novels & Stories, Volume One.

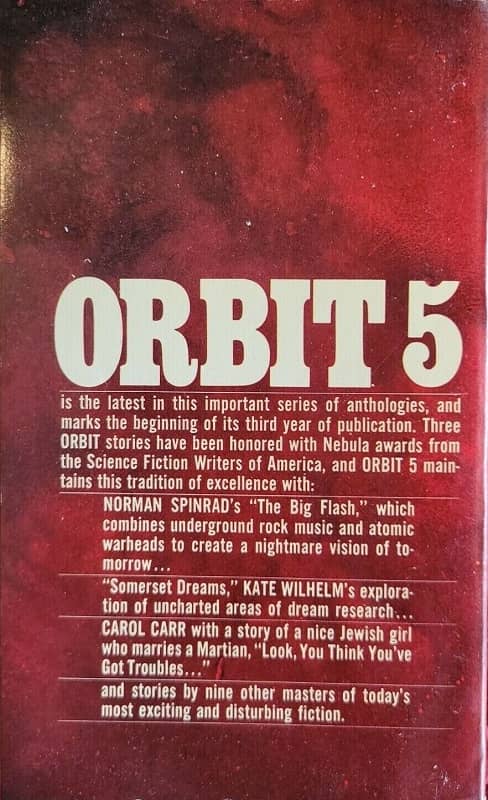

What’s going on here is a bit more complex than that, as we’ll see, for that’s the aspect of this story – or of this story’s history – that I wanted to look at more closely. So I bought a used copy of Orbit 5, the original anthology (edited by Damon Knight) in which “Winter’s King” first appeared, and reread the story in both versions.

I’ll begin with a summary of the story – and, as usual with these pieces, I’ll announce in advance that there will be spoilers! And, also, that as with most of the best stories, spoilers don’t matter. I’ll use yet a third set of pronouns for the protagonist: they/them/their.

The story opens on the planet Winter, with “the young king, the pride of his people” in a desperate situation – barely (if at all) clinging to sanity, filthy, trembling, and in fear discussing an assassination attempt, and the appropriate, violent, response. Shortly later the king is discovered, apparently drugged, in a bad part of the capitol city, and once returned to the Palace, announces that they must abdicate. It’s clear the king, Argaven, was abducted and “mindformed” – implanted with dangerous compulsions. But to do what? Abdicate? Or something worse? Argaven knows their mind – and Argaven knows it was their decision to abdicate – to avoid worse consequences, such as acting on compulsions given him by the mindforming. They ask for help from Axt, the Plenipotentiary of the Ekumen to Winter – perhaps the technology of the Ekumen has a way to cure the damage to their mind. So Argaven escapes to Ollul, 24 light years away. Which means, given the “nearly as fast as light” space travel of the Ekumen, that it will be more than 50 years before Argaven Harge can return to Winter, if ever, though they will only have aged a couple of years. A regent is appointed, until Argaven’s child, Emran, can take the throne.

|

|

Hainish Novels & Stories, Volume One ( The Library of America, September 2017)

On Ollul Argaven, now called Mr. Harge, is indeed cured of the damage caused by the mindforming, and they also learn what they can about science and sociology and the history of the Ekumen. And after a few years, they return home, now perhaps about 35 years old subjective, to serve as part of the staff of the Ekumen’s representative to Winter. But upon arrival, they are greeted by people who call them the true King – it seems Emran’s rule has been a disaster, and a revolution has begun – with Argaven, the beloved former King, the perfect leader. And soon they succeed, and the story ends with a powerful final picture, Argaven over the body of their dead (by suicide) child.

I’ve always found that a powerful story, particularly the use of time dilation to set up that closing scene – Argaven, once and future King of Karhide, standing over their own child, who succeeded them and whom they have succeeded. Besides that, it’s exciting, and colorful, and incorporates some interesting SFnal speculation, not just the time dilation aspect but the depiction of the Ekumen and its goals. It also incorporates one of the weird features of much SF (and even more fantasy) – a polity ruled by a monarchy. I’ve often found this aspect curious for stories set in a high-tech future, though it is reasonably well explained here, and of course is necessary for the working out of the plot.

As I noted, my first reading (first few, indeed) was in The Wind’s Twelve Quarters. On rereading the story in Orbit 5, I found it not quite as successful. What was it missing? Or was it yet another story that lost some impact over time? Or that struck me differently as an older man? I reread the revised version, and, magically, it was a great story again! Maybe the only difference was my mood at the time of reading?

|

|

Orbit 5 (Berkley Medallion, December 1969). Cover by Paul Lehr

So I took a closer look at the differences. The advertised difference, of course, is the use of she/her/hers pronouns for the Gethenians. (Gethen as the local name for Winter is also used (just a bit) in the revised version but not the original.) This is done meticulously, while traditionally male titles such as King are retained. And the change does affect our reading, our perception of the characters.

It’s more than just pronouns, however. Le Guin has added references to the social differences caused by the sexual differences between Gethenians and other humans of the Ekumen. Most importantly, the references in the original version to Argaven’s Spouse are excised. Those references were very slight in the original, and indeed the disregard of the Spouse came off a bit odd – Argaven leaves without any apparent consideration for her, who seems to be absent even though her child remains with Argaven. This is not necessarily unusual in royal marriages, I suppose, even on Earth, but when you pause to think about it in this story, it’s a bit awkward.

In the revised version, Emran is a child of Argaven’s own body; and there is no wife (or Spouse) as such. This elides the awkwardness of the Spouse’s absence from the story, and it also increases the power of Argaven’s two scenes with Emran, and of the depiction of her relationship to her child. In addition, in the original version, Emran has a son, a Prince (named Argaven!), who has been killed, meaning the heir is not from the main line of the Karhide royal family. In the new version, Emran is said to have no children of her own body, but she has sired six children, one of whom has been named heir. There’s a sneaky implication about Emran’s character there (intended or not, I don’t know) but it also provides a nicely different flavor to the question of the legitimacy of the Succession.

The name of Emran’s designated heir is Girvry, incidentally, which is motivation for Argaven’s climactic line in the revised version: “The Kings of Karhide are named Argaven, and Emran.” Le Guin added that line to replace the touching revelation in the original of the name of the dead Prince, son of Emran: “His name was Argaven.” That’s nicely done, but I always thrilled even more to the line in the revision, and missed it in the original.

There are a few more changes related (I trust) to Le Guin’s realization that the Gethenians are dual-sexed, most obviously an added sentence to the paragraph about what Argaven learns on Ollul: “She learned that single-sexed people, whom she tried hard not to think of as perverts, tried hard not to think of her as a pervert.” (This line replaces an unconvincing reference that seems to imply a cliched hospitality custom in Karhide: “it is better not to accept the loan of a Perifthenian’s spouse”.) (There’s also a mention of Argaven being tired of the state of perpetual kemmer in which most of her fellow students on Ollul persist. There is no mention of any sexual life for Argaven on Ollul.)

One further change puzzled me a bit: in the original version, Argaven’s absence while he was kidnapped is passed off officially as a hunting trip; but in the revised version, though hunting is mentioned once, after that simply it is called simply a trip to the mountains, and the activity is mountain climbing. At first I thought that was an odd genderization of “hunting” as a male-only sport, but on reflection I think she was papering over a slight inconsistency in the original version, as the diet in Karhide (in both versions) is stated to be mostly vegetarian. Or, maybe, she just wanted to add some variety.

All these changes, this acknowledgement of what Le Guin didn’t (consciously) know while writing the original version about the Gethenians’ sexual expression and resulting social organization, while not central to the main story, definitely deepen the story, add power and pathos and SFnal interest. The female pronouns by themselves (different from the pronouns in The Left Hand of Darkness) are also effective (to this reader) in pushing one away from unthinking gender-based assumptions about the Gethenians.

Finally, my close rereadings revealed other differences. Given the opportunity, Le Guin also revised the prose. It’s not so much a complete rewrite, but a great deal of tightening, slight improvements to rhythm, a few slightly cliched phrases altered. There are only a couple of outright additions, such as a sweet reference to childhood comforts she remembers while in captivity, and some much more evocative description of her discovery after the kidnappers release her. Prose is the sometimes hidden, or overlooked, secret to great fiction. The same plot, the same characters, are elevated by being presented with excellent prose. Le Guin was a strong writer already when she published the original “Winter’s King,” but five years later, either because she kept improving, or because taking another close look at the piece gave her the chance to make some better choices, the prose in the revised version is even better. I think the revisions make a good story a very good story.

Rich Horton’s last short fiction review for us was the “Summer 1950,” issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over a hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

Thank you, Mr. Horton, for taking the time to track down the original “Winter’s King” in Orbit 5 and comparing the two versions. I read the story in The Wind’s Twelve Quarters (a collection so good I ran out to buy the original Earthsea trilogy books based on reading the 2 included Earthsea stories), but I never went that extra mile, in spite of (because of?) Ms. Le Guin mentioning the differences.

I think that the use of the time dilation effect had less impact on me due to Ms. Le Guin having used it so effectively in “Semley’s Necklace”, the first story in the collection, where the time dilation “reveal” is wonderfully analogous to the fantasy motif of time passing differently in Faerie, tying in neatly to the “legendary” atmosphere of the story.

You’re right about “Semley’s Necklace” and its use of the time dilation. I really love that story too. I suppose I should compare the original magazine version (“The Dowry of Angyar”, though as I recall Le Guin said it should have been “Dowry of the Angyar”) to the version in ROCANNON’S WORLD to the version in THE WIND’S TWELVE QUARTERS. 🙂

The slightly different effect of the time dilation in “Winter’s King” (like the song “I’m My Own Grandpa”, to make a particularly ill-chosen comparison! 🙂 ) works as well for me as the effect in “Semley’s Necklace”.

Sounds like the revisions gave the story an added dimension?

I’m reminded of the Ancillery Justice series. Sans its ambiguity about gender, the trilogy is a typical space opera. Maybe the first draft was space opera until Leckie decided to introduce what would become a central conceit? Just like le Guin.

Good question about ANCILLARY JUSTICE … hmmm … Ann actually discussed some of that when she visited my local indy book store (Left Bank Books in St. Louis) and I can’t remember for sure what she said. I do know that the first draft (which was changed IMMENSELY over time) was started about a dozen years before the novel came out.

I should say that Left Bank Books is as local to Ann as it is to me — we live a mile or two away from each other.

[…] The Wind’s Twelve Quarters). Rich Horton has written an article about the differences at Black Gate. 2. This piece is a “Hainish” story, and one set on Gethen, the same planet that featured in […]