Cleve Cartmill, The Devil’s in the Details

|

|

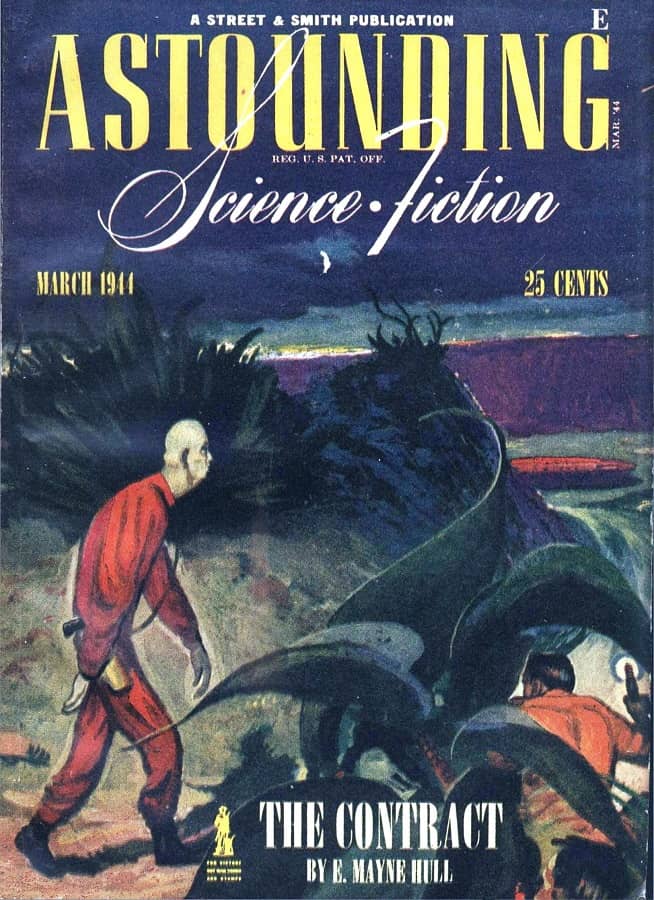

Astounding Science Fiction, March 1944, containing “Deadline” by Cleve Cartmill. Cover by William Timmins

Pulp writer Cleve Cartmill (1908 – 1964) is probably best known for writing the story that prompted an FBI visit to John W. Campbell’s office at Astounding. The story in question, “Deadline” (March, 1944), featured a bomb eerily similar to the one being developed by the Manhattan Project at the time. As an educated science fiction audience, Black Gate readers probably do not need that old story re-hashed. Instead, I’ll tell you about three of Cartmill’s fantasy stories published in Unknown, all of which are interesting and worth reading.

Historically, Cartmill is considered a competent but undistinguished pulp writer. In A Requiem for Astounding, Alva Rogers writes — “Cartmill wrote with an easy and colloquial fluidity that made his stories eminently readable.” I agree. But I also think there’s more to him than that. In the three pulp fantasy stories I’ll be reviewing here — “Bit of Tapestry” (1941), “Wheesht!” (1943), and “Hell Hath Fury” (1943) — Cartmill examines some deeper themes including free will and what makes us human. Although he doesn’t always follow through on these ideas, you are asked to think about them.

As a heads up, there will be heavy spoilers in this article.

Table of Contents for Astounding, March 1944

For those who have not investigated pulp fantasy let me begin with an overview of what it is, and what it is not. In general terms it is cousin to contemporary urban fantasy. And even when a pulp fantasy story features fairy people — gnomes, leprechauns, etc. — it is rarely a high fantasy or Tolkeinesque. It often features mythological characters, even pagan gods. And here’s the big ticket item — Satan himself is often a character in pulp fantasy stories. Sometimes he’s even mentioned in a title such as “Satan Sends Flowers” (1953) by Henry Kuttner. Imps, demons, devils and locations of Hell and Purgatory/Limbo are commonplace. Another interesting feature is the surprising cross-over between fairie folk and the demonic realms.

Religion and mythology are often put into a blender in these tales, so you might see a hokey magician send someone to Hell. Or a hidden bar filled with hard-drinking fairie folk, mythological figures, and perhaps a Greek god, or two. All of these strange folk seem to know each other and they interact just out of humanity’s sight. Like urban fantasy, pulp fantasy has its hybrids — changelings, demigods, and half-demons.

Protagonists in these stories generally lack a sense of wonder about otherworldly creatures. More often than not, they’re concerned that these visitations are the result of delirium tremens (DTs). Heroes generally don’t want to be whisked away to fairyland, instead wanting rid of the craziness and a return to normal life a.s.a.p.. Many pulp fantasy stories are quite funny, reading like screwball comedies. Others are serious with complex and heavy undertones. Although Cartmill’s “Wheesht!” has humorous elements, it’s by and large a serious story. “Bit of Tapestry” and “Hell Hath Fury” are both somber.

|

|

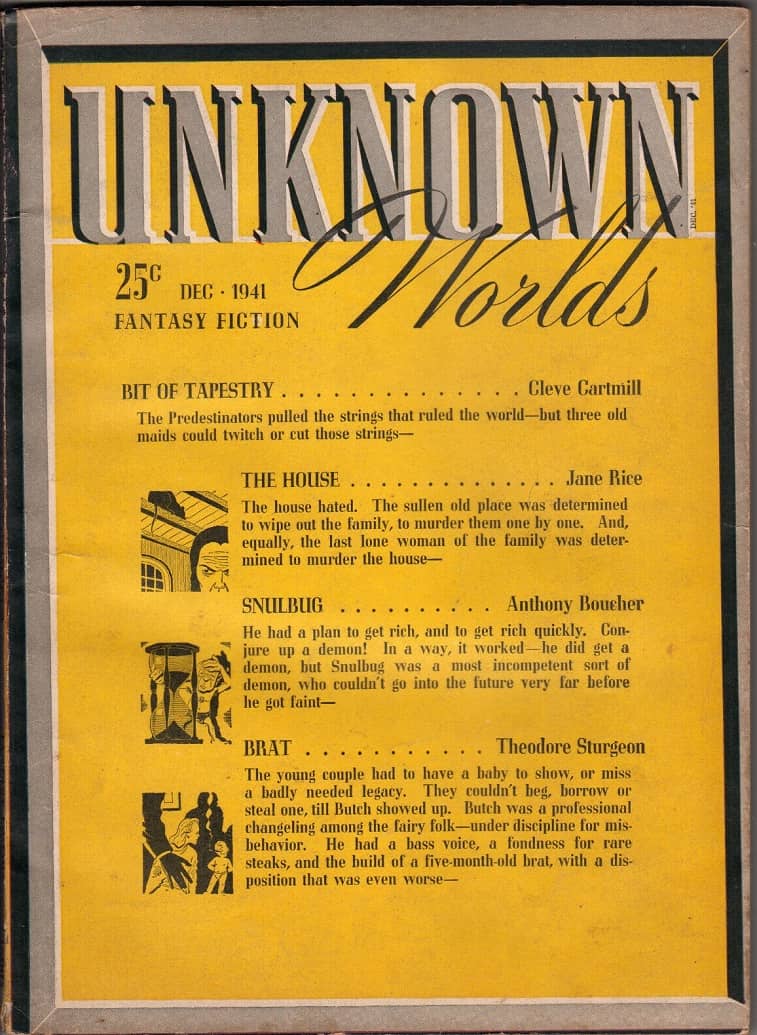

Unknown Worlds, December 1941, containing “Bit of Tapestry,” by Cleve Cartmill

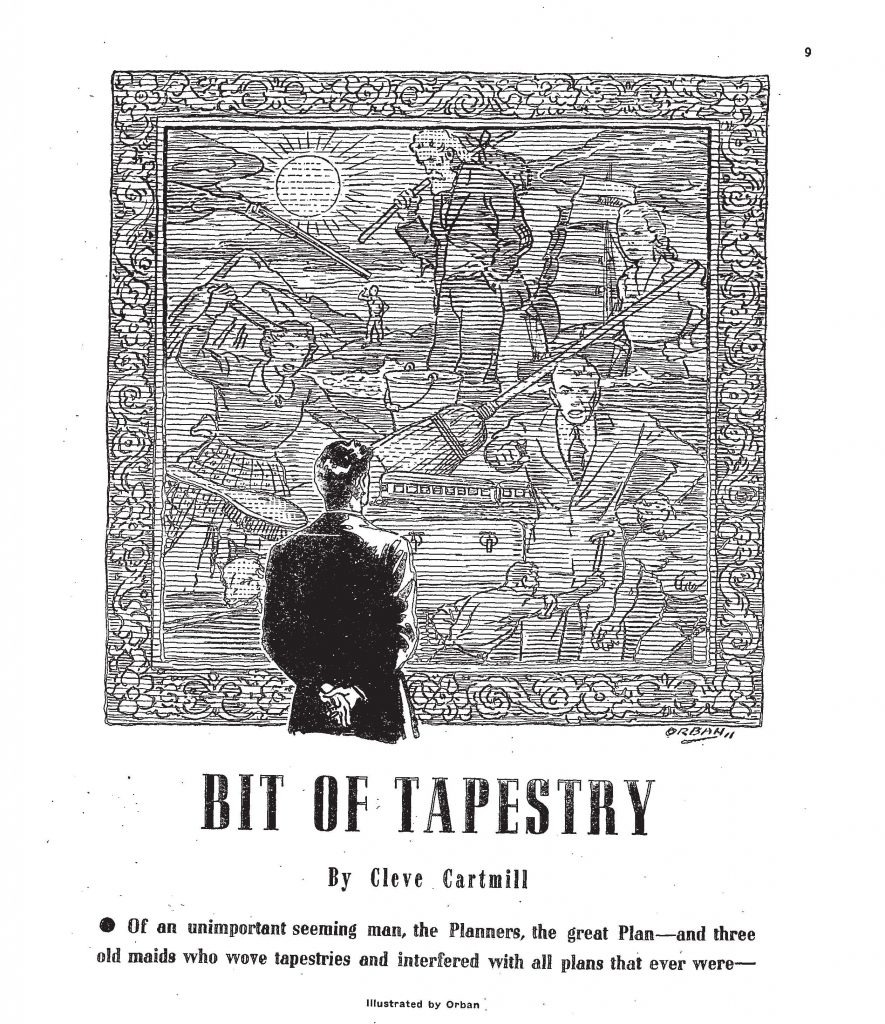

“Bit of Tapestry,” Unknown Worlds, December 1941

“Bit of Tapestry” is a complex story. In actuality the plot is outlined by some extradimensional entities before it even begins. But this is so obscure as make little sense until the entire story is read and digested. One wonders who these characters are and why they have the right to meddle in the affairs of humans. This is not answered, although we can recognize some of the characters as “Fates” — the original three Norns and perhaps others as well.

The plot centers around a man named Webb Curtain who is not mad and a mysterious briefcase that needs to be delivered to H. William Karp. It features a trio of old maid sisters who seem to be combination of the Norns from Norse mythology and the Greek, Grey Sisters (Graeae) who shared one eye and one tooth between them. In this story the three old maids seem to play name games — different ones have sight and hearing at different times — making them seem even more like the Grey Sisters. But Fate is not the only symbolic representation in the story. Death also makes an occasional appearance as a gardener named, Louie.

What I find most interesting about “Bit of Tapestry” is that it touches on the idea of free will, who has it and who doesn’t. What happens when you lose your free will? Can anyone deprive you of it? Webb is supposed to kill himself at the beginning of the story, in despair over his parents double suicide. But he doesn’t. He steps outside of the preordained plan and acts with free will. As soon as he does this the townsfolk, who’ve known him all of his life, shun him as a madman. His parents weren’t really mad either, you get the feeling that they were driven to their actions by some kind of cosmic force. Suddenly, Webb is in the Twilight Zone — he’s fired from his job, no one trusts him, and in fact, will barely speak to him. All but one friend turns against him, and others begin to accuse him of violence that he hasn’t committed. Eventually, he’s even blamed for a disaster directly brought about by an angry mob trying to kill him. Web knows he’s not mad but at moments begins to wonder.

Millicent Lake is the other character in the story who moves outside the pattern and acts with free will. She’s an unusually vibrant woman when we first meet her and Webb can’t help but fall in love, as she’s fallen for him. Like attracts like.

Millicent Lake is the other character in the story who moves outside the pattern and acts with free will. She’s an unusually vibrant woman when we first meet her and Webb can’t help but fall in love, as she’s fallen for him. Like attracts like.

Millicent tells Webb about a scary incident which drove her from her home in another city. A creepy neighbor who had the hots for her droolingly showed her the plans of an invention which he claimed would make him a fortune. When she cannot grasp the purpose of the device he becomes enraged and chases her out of his apartment and down the street. He’s stopped by a good Samaritan and she leaves town, taking the train to Webb’s hometown, to stay with her cousin, Kay. Kay happens to be Webb’s childhood friend and sometimes girlfriend. When Millicent gets into town she’s informed about an inheritance from a recently deceased uncle. She must remain in town for a week until it’s ready to be given to her. She tells Webb that she feels an unseen hand is keeping her there. And that she and Webb were never supposed to meet.

When she learns about the mysterious briefcase in Webb’s possession she feels sure the thing is bad news and interferes with it getting to where it needs to be. She’s suddenly informed that her inheritance is ready and then something happens to her. Webb notices a huge difference immediately. She’s lost some of her unconventional ideas and all of her “shine.” In a word, she’s become ordinary and Webb is astonished, and scared. She tells him she no longer loves him. At this point Webb knows his adventure is coming to a close and wonders what will happen to him after it’s over. In the end, he also loses his shine and becomes ordinary. He’ll lead a happy life with Kay, but there’ll be no fire in it.

What is Cartmill saying here about fate? There are several speeches in the story about the acceptance of fate and lack of free will in the course of life. I would have wished for more clarification by one of the characters, perhaps one of the sisters, about this. The answer remains obscure — do humans even have free will? It’s a bit murky but my conclusion is that Cartmill believes we don’t. Too bad, as I happen to disagree. Still, it’s an intriguing story, and well worth reading.

“Wheesht!”, Unknown Worlds, June 1943

This is a war-time story about a counterespionage agent on the home front whose family happens to have a leprechaun attached to it. Our hero is Mike O’Brien (his undercover name is James Hineman.) When Uncle Pete (O’Brien) dies, Seag, the leprechaun, comes from Ireland to live at Mike’s house. The creature is a pleasant fellow with a few goals. He seeks to protect the family line and keep Mike out of trouble. Mike isn’t yet married but he knows a nice Irish girl who likes him, so Seag has an eye on her too as a potential bride. Meanwhile, counterespionage agent Mike is trying to get in good with a Nazi collaborator so he can get the names of the rest of an insidious spy ring (with cells all over the country.) Mike can’t tell Seag about his spy work so the leprechaun thinks Mike’s become a liar and a cheat. Worse, a cad for being mean to the Irish girl — Nadeen. So we have a three-way pull in this story between Mike, the Nazis, and the leprechaun. Moreover, we also see an interesting overlap between faerie mythology and traditional Christian afterlife.

Seag believes that Mike has turned traitor to his country and determines to scare him straight. To do this he’ll send him to Hell for a short course of torture. Seriously. Quickly, Seag discovers that getting Mike out again is not going to be easy as he thought and so Mike must come up with his own get-out-of Hell-free card. I won’t give that part away. In the end, Mike completes his mission and breaks the spy ring, eventually letting Seag in on the truth. The story ends as it began, with a pile of loose vegetables in the middle of the living room. Read this one, it’s highly enjoyable.

“Hell Hath Fury”, Unknown Worlds, August 1943

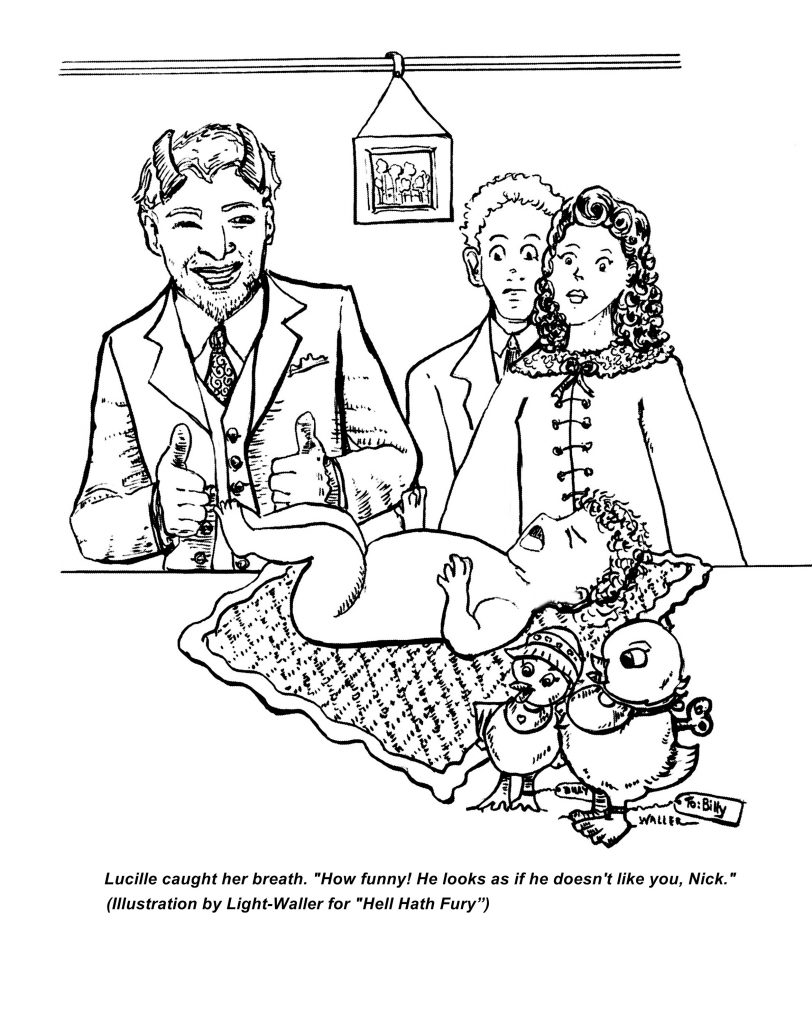

Billy Roberts is special, unique. He’s a half-demon, a diabolical experiment meant to enhance the powers of Hell. Even as a baby, Billy is aware of his demonic nature, and of Old Nick who comes by to look in on him. With that first look, infant Billy wages war upon the Devil, deciding that he won’t be controlled. Old Nick, a cross between Santa Clause and an old lecher, finds this amusing. Billy grows into boyhood with Old Nick keeping an eye on him as a friend of the family. Even as a boy of eight, Billy finds he has a knack for manipulating people. He thinks it’s fun and the unexpected results are far-reaching — he’s unknowingly set a group of people on the road to Hell.

His demonic father comes to visit him at night as a shade and tells him how proud he is of him. Billy is disgusted when he learns the long-term results of his childish pranks and decides he’s going to change his ways. He’s told that the demons have a goal to produce a bunch of Billies, an organized cabal of evil that’s bent on the destruction of humanity’s moral fiber. But they have to see how Billy does first.

As a teen, Billy tries to fix some of the mess he’s created. He has some success and Hell doesn’t like it. One night, a demonic supervisor (like a shop foreman) comes to reason with him. In this case, the reasoning involves torture. Billy doesn’t give in and keeps trying. His demonic father is worried, the boy is betraying his heritage. The other demons want to punish him and Old Nick watches with a glint in his eye. He doesn’t care so much of the exact outcome, he’s more interested in seeing the experiment play out.

Eventually, Billy consults a library book on magic and finds an herb that might protect him from his midnight torturers. The problem is that he’s also affected, just touching the English Rue (Rue is also called the Herb of Grace) makes Billy feel sick. Somehow he manages to make a circle of the herb around his bed, then lays down, too sick to move. The torturers come back that night and this time they’re magicians who can apply pain from outside the circle. Billy’s human parents grow frantic the next morning when they see the boy’s poor condition. The local doctor wants to send him to the hospital but Billy refuses. Old Nick shows up but won’t (or can’t) come into the bedroom. He asks Billy’s human father to carry him out to the living room and this is done against Billy’s will. Away from the Rue, Billy’s strength returns. Old Nick tells the parents that the boy needs a sulphur bath to recover and he’ll take Billy to get one. The grateful parents wave them off and Billy follows Nick down a winding path and into Hell itself. There he’s put on trial. Billy is strong and unrepentant and Nick, now seen more clearly as a Prince of Hell, blames the demons at court for the ruination of the experiment. Billy’s human half has proven the stronger. Now Nick and his infernal council will decide what’s to be done. Soon, Nick returns Billy home and with the boy’s first cheerful words — “Hello, mother!” and “Hello, dad!” we know that had something’s changed. He’s not the sullen boy he had been and that’s a bad sign.

In the next scene we seen him a few years later and he’s become an awful jerk. An uncaring man with rigid morals and a cart-load of self-interest. Old Nick sees him one last time and we are assured that Billy, now Robert, is fully human. That’s what the infernal council did, they took away his demonic half. And we see that he is now, certainly, a man destined for Hell. Nick confirms this fact as he says good-bye.

For me, the ending doesn’t carry through. Throughout the story Billy’s been fighting his demonic nature and trying to do good. At the trial he shows great courage and Nick acknowledges that humanity is stronger than demonkind. But when Billy is made fully human he becomes a royal bastard. Why? Was it only the struggle that made him want to do good? To be strong? Of course, being a demon spawn, Billy was damned at the moment of his conception. But does this mean there can be no redemption for him? I don’t necessarily mean religious redemption but good karma brought about through good acts. In the end, it seems that his free will has been removed along with his demonic half. But do demons even have free will? I don’t think they’re supposed to. Anyway, if humans are stronger than why did Billy lose the desire to help people, to even see them as good when he became fully human? I would have preferred to see him struggling as an adult, maybe even homeless and hard on his luck, but knowing who he was and still trying to do good. Admittedly, this kind of ending fits more with an urban fantasy from the 1980’s than a pulp fantasy from the 1940’s. Still, Billy’s triumph is what? A few years of mastery on Earth before the pit? Something falls flat there for me. The story is good and well-crafted, but the ending left me a bit cold.

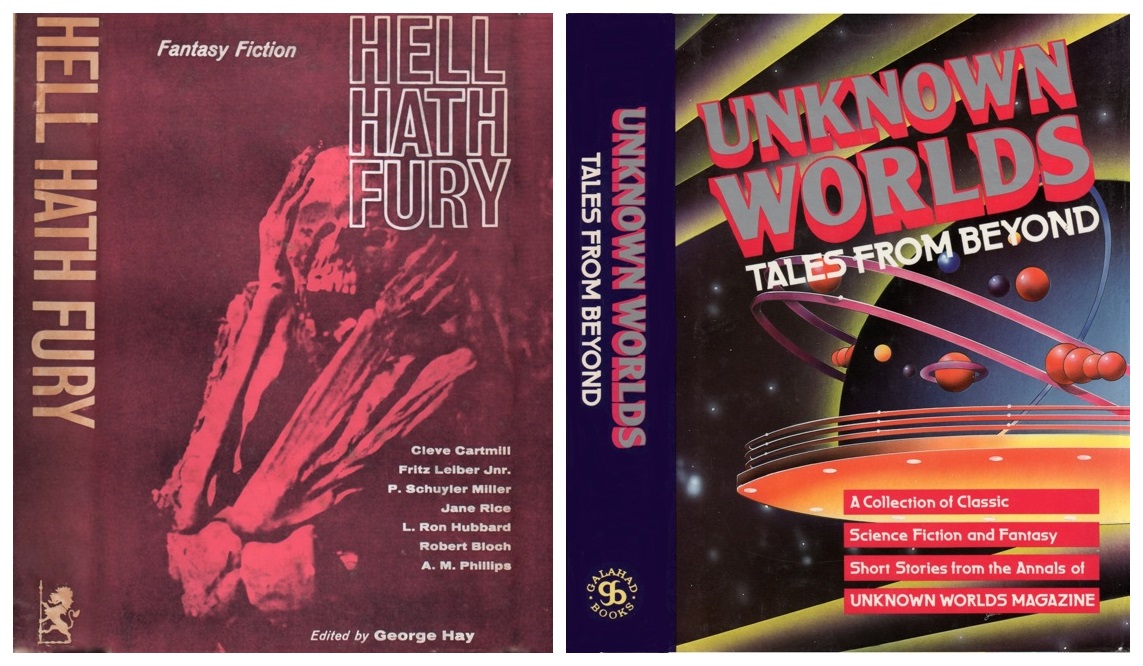

“Hell Hath Fury” was reprinted in Hell Hath Fury (1963) and in Unknown Worlds: Tales from Beyond (1988). “Wheesht!” and “Bit of Tapestry” were never reprinted. You can read all three in old issues of Unknown which can be found online as PDF’s.

SARA LIGHT-WALLER is a writer, illustrator, and avid pulp and vintage science fiction & fantasy fan. In 2020, she won the prestigious Cosmos Award for her illustrated space opera story — “Battle at Neptune.” She’s published two illustrated new pulp books — Landscape of Darkness and Anchor: A Strange Tale of Time and is a regular contributor to several pulp blogs.

The illustration seen here for “Hell Hath Fury” is entirely new for this article. It is copyright, Sara Light-Waller, 2022. All Rights Reserved. Permission to copy it must be given by the artist. Please contact Sara if you’d like to share it. Thanks!

Catch up with Sara at Lucina Press.

[…] the link to “Cleve Cartmill, The Devil’s in the Details”. Feel free to leave a comment on the site or here, I’d love to hear from […]