Always Then and Never Now: The 13 Clocks by James Thurber

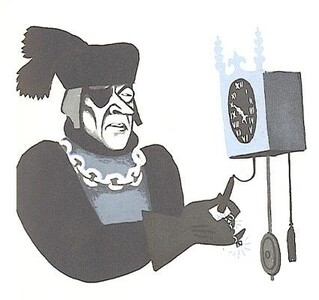

ONCE upon a time, in a gloomy castle on a lonely hill, where there were thirteen clocks that wouldn’t go, there lived a cold, aggressive Duke, and his niece, the Princess Saralinda. She was warm in every wind and weather, but he was always cold. His hands were as cold as his smile and almost as cold as his heart. He wore gloves when he was asleep, and he wore gloves when he was awake, which made it difficult for him to pick up pins or coins or the kernels of nuts, or to tear the wings from nightingales. He was six feet four, and forty-six, and even colder than he thought he was. One eye wore a velvet patch; the other glittered through a monocle, which made half his body seem closer to you than the other half. He had lost one eye when he was twelve, for he was fond of peering into nests and lairs in search of birds and animals to maul. One afternoon, a mother shrike had mauled him first. His nights were spent in evil dreams, and his days were given to wicked schemes.

Wickedly scheming, he would limp and cackle through the cold corridors of the castle, planning new impossible feats for the suitors of Saralinda to perform. He did not wish to give her hand in marriage, since her hand was the only warm hand in the castle. Even the hands of his watch and the hands of all the thirteen clocks were frozen. They had all frozen at the same time, on a snowy night, seven years before, and after that it was always ten minutes to five in the castle. Travelers and mariners would look up at the gloomy castle on the lonely hill and say, “Time lies frozen there. It’s always Then. It’s never Now.”

So begins James Thurber’s wonderful fairytale The 13 Clocks. Best known as a cartoonist, humorist, and one of the stalwarts of the New Yorker during the Harold Ross and William Shawn years, he also wrote several fairytales for children. I haven’t read the others — Many Moon and The White Deer — but I have come back to this one several times. An effervescent read, it never fails to delight.

As described in that magnificently menacing opening, the evil Duke spends his days setting his niece’s suitors impossible tasks such as cutting a slice of the moon or turning the ocean to wine. Sometimes, for no better reason than failing to describe his different-length legs properly (they differed in length because he spent his youth “place-kicking puppies and punting kittens”) or not praising his wine, staring at his niece too long, or having a name that started with X, he would just kill them.

One day, a tatterdemalion minstrel named Xingu appears in the town below the Duke’s castle singing songs poking fun at the Duke. In reality, he’s Prince Zorn of Zorna come to win the hand of Saralinda. At evening he is approached by an odd man offering to help him.

A soft finger touched his shoulder and he turned to see a little man smiling in the moonlight. He wore an indescribable hat, his eyes were wide and astonished, as if everything were happening for the first time, and he had a dark, describable beard. “If you have nothing better than your songs,” he said, “you are somewhat less than much, and only a little more than anything.”

“I manage in my fashion,” the minstrel said, and he strung his lute and sang.

“Hark, hark, the dogs do bark,

The cravens are going to bed.

Some will rise and greet the sun,

But Whisper will be dead.”The old man lost his smile.

“Who are you?” the minstrel asked.

“I am the Golux,” said the Golux, proudly, “the only Golux in the world, and not a mere Device.”

“You resemble one,” the minstrel said, “as Saralinda resembles the rose.”

“I resemble only half the things I say I don’t,” the Golux said. “The other half resemble me.” He sighed. “I must always be on hand when people are in peril.”

“My peril is my own,” the minstrel said.

“Half of it is yours and half is Saralinda’s.”

“I hadn’t thought of that,” the minstrel said. “I place my faith in you, and where you lead, I follow.”

“Not so fast,” the Golux said. “Half the places I have been to, never were. I make things up. Half the things I say are there cannot be found. When I was young I told a tale of buried gold, and men from leagues around dug in the woods. I dug myself.”

“But why?”

“I thought the tale of treasure might be true.”

“You said you made it up.”

“I know I did, but I didn’t know I had. I forget things, too.” The minstrel felt a vague uncertainty. “I make mistakes, but I am on the side of Good,” the Golux said, “by accident and happenchance.”

The Golux gives Prince Zorn advice that keeps the Duke from killing him outright for having a name that begins with X. Instead, the prince is set an impossible task: in 99 hours he must bring the Duke 1,000 jewels and restart the clocks. Together, the prince and the Golux, set off in search of Hagga, a woman rumored to cry tears that turn into jewels.

Meanwhile, the Duke sits in his castle alongside his spies Hark and Listen (he’d earlier fed another spy, Whisper, to his geese) in eager anticipation of various plans coming to fruition. He’s also haunted by thoughts of the Todal.

“What’s the Todal?”

A lock of the guard’s hair turned white and his teeth began to chatter. “The Todal looks like a blob of glup,” he said. “It makes a sound like rabbits screaming, and smells of old, unopened rooms. It’s waiting for the Duke to fail in some endeavor, such as setting you a task that you can do.”

In the end, quests are finished, mysteries revealed, and order restored, all as it should be in a fairy tale. The hero is heroic, the villain dastardly, and the Golux mysterious.

As enchanting as the narrative of The 13 Clocks is, so are the prose and the illustrations. Rhymes, wordplay, and all sorts of bits of fun fill the book’s pages. It’s also quite beautiful at times.

It was cold on Hagga’s hill, and fresh with furrows where the dragging points of stars had plowed the fields. A peasant in a purple smock stalked the smoking furrows, sowing seeds. There was a smell, the Golux thought, a little like Forever in the air, but mixed with something faint and less enduring, possibly the fragrance of a flower.

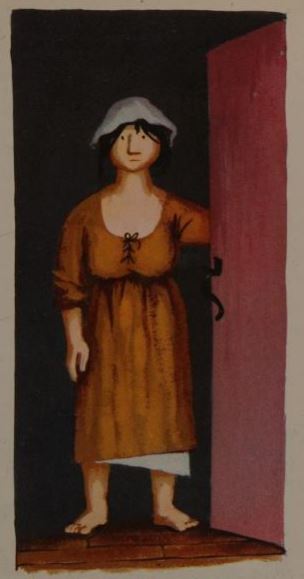

Thurber had been known for his cartoons, but by the time he wrote The 13 Clocks he was nearly blind. He sought the services of his friend Marc Simont for the book. According to Wikipedia, in order to ensure Simont was up to the task, “Thurber made Simont describe all his illustrations, and was satisfied when Simont was unable to describe the hat.” The resulting pictures are wonderful and appropriately dark and spooky in some places and warm and human in others.

I can’t remember when I first was made aware of The 13 Clocks. It wasn’t a book I ever saw on any school or public library shelves when I was little and devouring anything of the sort I could get my stumpy little fingers on. When I did learn of the book as a middle-aged man, I kept my eyes open for a copy. One day at an estate sale only a short piece from my home, there it was in all its dark and purple hues. For 50¢, I walked away with a seventh printing of the original edition. I’ve paid plenty for plenty of books in my life, but few of them have turned out to have really been worth it. That paltry 50¢ is maybe the best exchange I’ve ever made for a book.

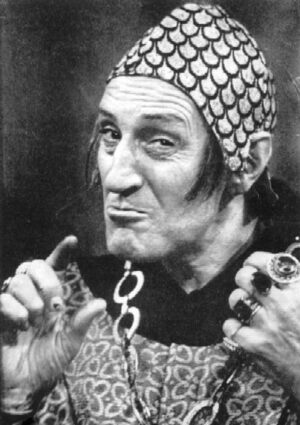

Now it’s all over the place having been republished as part of the New York Review Children’s Collection with an introduction by Neil Gaiman. Over the years there have been radio productions, plays, an opera, and even a tv production starring Basil Rathbone as the Duke, something I might give my eyeteeth to see.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

Damn, Fletcher! You beat me to it! I’ve been intending to write an appreciation of this wonderful book for years…

Anyway…I too didn’t come to the book until I was an adult, though I’ve loved Thurber ever since picking up a battered paperback copy of My Life and Hard Times in a seventh grade history class. The Thirteen Clocks has things in it that will stay with you forever, such as: “The two white horses snorted snowy mist in the cool green glade that led down to the harbor. A fair wind stood for Yarrow and, looking far to sea, the Princess Saralinda thought she saw, as people often think they see, the distant shining shores of Ever After. Your guess is quite as good as mine (there are a lot of things that shine) but I have always thought she did, and I will always think so.”

It’s a unique and beautiful book, and beyond price to me.

Sorry, sir. I read it aloud to my wife when I bought it. She didn’t really remember that, but as she edited the article, it all started to come back to her. It’s such a delight.

I read it to my kids – it’s a tricky read-aloud!

I need to read the other two books

I have a copy of this but haven’t read it. This makes me want to.

It’ll cost you an hour, one you find definitely worth spending.

Lin Carter loved this book; he said the effect was as if Thurber had tried to write it in verse but couldn’t get it to scan.

I think I read something that that was all deliberate on Thurber’s part, hiding and weaving the poetry into the prose.

Oh yes – Carter wasn’t implying that falling just a little short of actual verse was a failure on Thurber’s part; it was his intention.