My Robert A. Heinlein Problem

Do you know someone — a friend, a coworker, a family member — whom you esteem for their many good qualities… and yet whose extreme and undeniable character flaws can sometimes make you want to banish them from your life forever? Of course you do. (Humility and the law of averages should also make you acknowledge that for someone else you know, there’s a good chance that you are that person.)

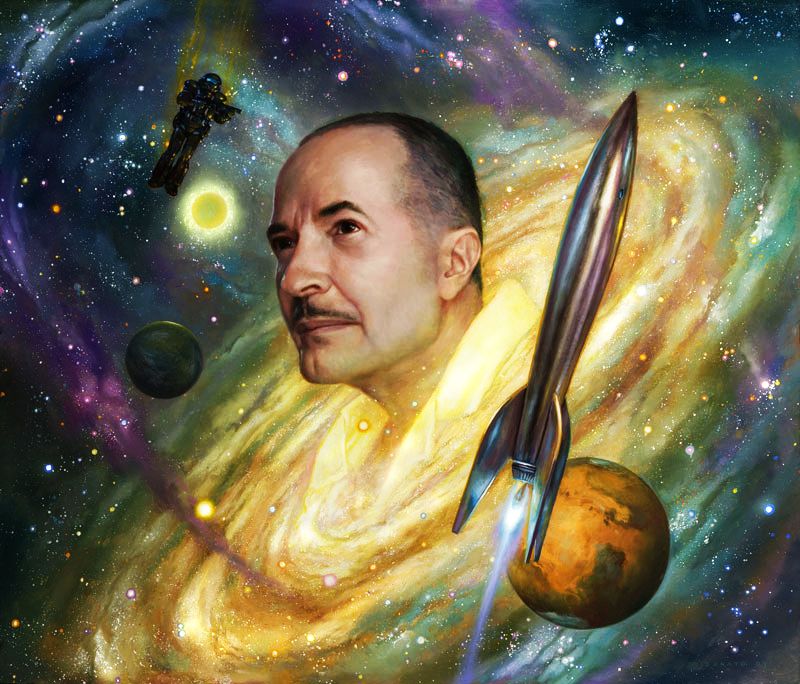

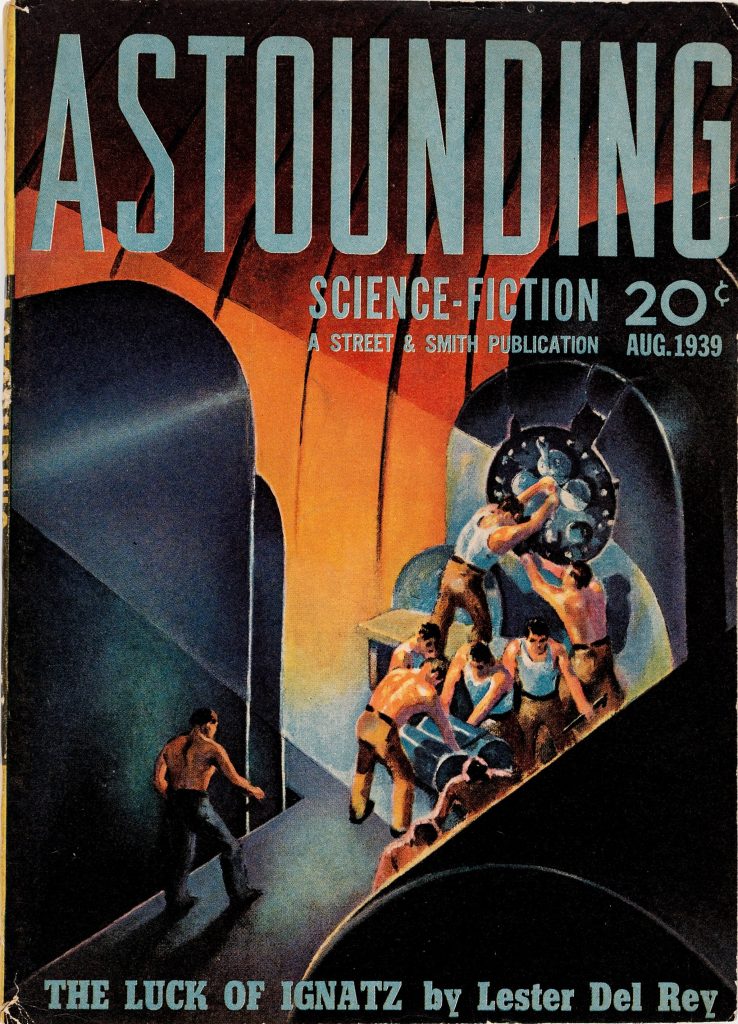

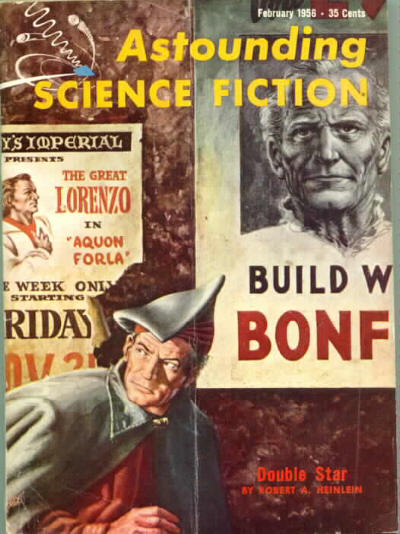

For me, that problematic individual is Robert A. Heinlein. Dominating the science fiction field from the moment his first story, “Lifeline,” appeared in the August, 1939 issue of Astounding Science Fiction to his death almost a half century later, Heinlein was arguably the most important writer in the history of American genre sf. In 1974 he was the first writer named a Grand Master by the Science Fiction Writers of America and was the winner of four Hugo Awards for best novel (and seven “retro” Hugos for works published prior to 1953). Invoking his name can start a passionate argument even now, and he’s been gone for thirty-three years.

For some, Robert A. Heinlein is the embodiment of golden age greatness, the all-wise Father of modern science fiction, the fountain from which everything flows. For others, he’s an embarrassing example of all that’s wrong with the genre, too white, too male, too American, a regressive relic best disowned and discarded. I know just how you feel, all of you, because I have a foot planted firmly on each side of the line.

On the one hand, I adore Heinlein’s work and on the other hand, I loathe it. I have to admit that the case for the prosecution is strong and impossible to ignore. On a purely technical level, his worst books (mostly the ones that appeared in the last two and half decades before his death in 1988) are intolerably talky, their plots immobilized by the dead weight of page after endless page of preaching and given a gloss of spurious profundity by increasingly solipsistic and self-referential authorial games. In their deadly blending of narrative tedium and pompous, egoistic shamanism, they are the very definition of self-indulgence.

As for actual substance, politically Heinlein too often came across as a crude power worshipper, though the charge of outright fascism that some make against him (an attitude best exemplified in the cartoonish Starship Troopers movie) won’t stick. An unapologetic believer in what are often called the “military virtues” (discipline, order, courage, devotion to duty), Heinlein certainly thought that the application of overwhelming force was a perfectly acceptable solution to a particular kind of problem, which is not all that surprising coming from a man of the World War Two generation.

On the other hand, one of the strongest impressions you get from Heinlein’s books is his hatred of official, bureaucratic authority, and his greatest delight is to see such arbitrary authority baffled, bullied, humiliated and routed; in any conflict between an individual and an organization, Heinlein is invariably on the side of the individual. Formally, he was a radical libertarian, but temperamentally, he went even farther than that; he was fundamentally an anarchist. For some that will be a virtue, for others a defect. Your mileage will vary, but even if you are in sympathy with his outlook, it must be conceded that whenever any situation calls for political solutions, Heinlein is only too ready to reach for a blunt instrument.

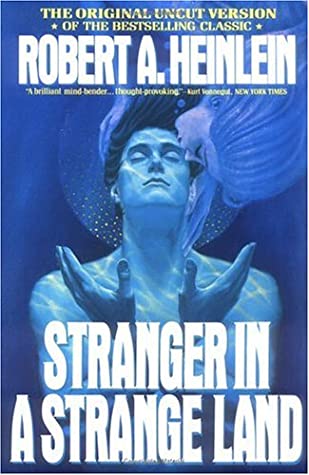

Heinlein’s attitude towards women is more problematic than his politics. Beneath a veneer of sexual liberation and social equality lies a patronizing paternalism that’s simply infuriating. For example, in the incoherent manifesto-cum-novel Stranger in a Strange Land (a book that is the key to all that is worst in Heinlein), the women are all completely liberated, and what do they choose to do with their liberation? Wait hand and foot on the pseudo-messiah Valentine Michael Smith and his mentor, Jubal Harshaw (who unceasingly yells “front!” and expects one or all of his infinitely pliable “secretaries” to come running up to cater to his every whim, and they do, with a patient indulgence and unfailing good humor that’s as divorced from reality as a Salvador Dali daydream). In Heinlein’s books (the later ones, especially) men often use terms of address like “little one,” “pretty foots,” “youngster,” “kid,” “dimples,” and similar infantilisms when speaking to their supposed female equals. “People lose teeth talking like that” as Humphrey Bogart said in the Maltese Falcon, but Heinlein’s women lap it up. I generally dislike language policing but a single paragraph of this sort of clueless condescension sets my teeth on edge and a whole page of it makes me want to scream and heave the book through the window.

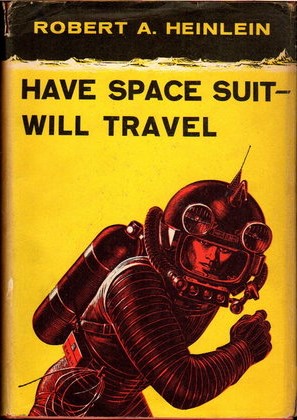

Add to all this the undisguised goatishness of a middle-aged male writer whose idea of a well-ordered world is apparently one in which an endless stream of beautiful, cheerfully compliant young women are sexually available to him on a no-obligation basis and you’ll see why most Heinlein fans are men. Giving such inflatable women fake agency by making them protagonists, as in the late novel Friday, doesn’t change the situation; in fact, it makes it worse by laying the hypocrisy of the exercise bare, so to speak. (Michael Whelan’s cover for Friday gives the game away — Raquel Welch should have sued.) Heinlein’s best female character is probably Patricia “Peewee” Reisfeld in Have Space Suit, Will Travel and significantly, she’s only eleven years old. I shudder to think what he would have made her after she reached puberty.

These are all severe shortcomings, but for me the moral coarseness that was often present, even in Heinlein’s best work, is what tells against him most. He divided everyone into two groups: the competent, free-thinking, and ruthless, who have a right to do as they want, and the incompetent, conventional, and stupid, who deserve to go to the wall. It leaves a bad taste in your mouth, even as Heinlein generously permits you to assume that you are one of the superior ones — after all, you’re smart enough to be reading one of his books.

Even as a kid, though, I knew that there are precious few science-fiction supermen in the world and that failing to win the genetic intelligence lottery doesn’t make you less of a human being; after all, most people are a flawed mixture of strength and weakness, sharpness and stupidity, competence and incompetence, and are just trying to muddle through as best they can in a world that is a hell of a lot bigger than they are. That much was clear whenever I looked at my family, my friends, my teachers, and yes, even (or especially!) myself.

The one time Heinlein seems to recognize this less than ideal reality is in Double Star, the story of Lorenzo Smythe, a ham actor shanghaied into impersonating a galactic politician who is recovering from an unsuccessful assassination attempt. At the end of the book, the politician dies and the Great Lorenzo assumes the role for life. After twenty-five years of “being” Joseph Bonforte, Lorenzo reflects back on what he has accomplished: “There is solemn satisfaction in doing the best you can for eight billion people. Perhaps their lives have no cosmic significance, but they have feelings. They can hurt.” That’s a rare note of compassion coming from the steel-plated competence-worshipper, and it makes Double Star Heinlein’s best adult novel. But when that note of empathy is absent, as it all too often is, Heinlein’s “every man for himself” ethos can make him a callous, morally repulsive writer.

So… the case for the prosecution rests. The verdict? Guilty, Your Honor. I can’t stand Robert A. Heinlein. To the bonfire with him and all his works! But wait — there is another case to be made, the case for the defense, and it’s imperative to make it, because I love Heinlein and there are too many books of his that I couldn’t do without.

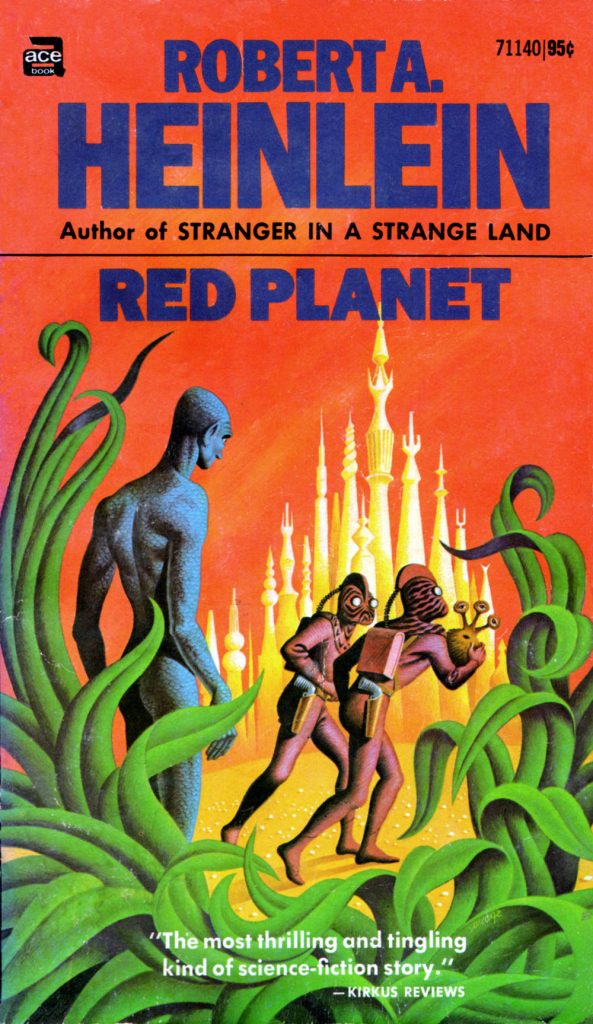

More than any other writer, it was Heinlein who drew me to the science fiction genre when I was a kid. When I first discovered them, his books exerted an irresistible pull over me; I was almost literally addicted to them. His juveniles were what I read first (in the Ace paperback editions with the wonderful Steele Savage covers), and in those books that I devoured one after the other like so many potato chips (except that you can’t eat the same potato chip five or six times, the way I compulsively reread my favorite Heinlein novels) — Have Space Suit Will Travel, Red Planet, The Rolling Stones, The Star Beast, Tunnel in the Sky, Space Cadet — the narrative voice is irresistibly beguiling, with its wisecracking, confidential tone. It was a voice that never talked down to me and told me that I was equal to anything life could throw at me because I was a human being with the divine ability to think. And being juveniles, many of the defects I’ve already mentioned were moderated or even nonexistent in those books, though they were still plenty sophisticated enough to be suitable for adults… who usually aren’t nearly as excited about thinking as young people are. Heinlein at his best could get you excited about thinking.

Reading those first Heinlein novels was like getting letters from a pen pal who lived in the future, messages that came from an incredibly exciting, optimistic place of continually unfolding wonders, full of fascinating problems and challenges — but a concretely realized, completely believable place that one day I was going to get to live in, too. Even in those books, Heinlein had a weakness for a good lecture, but the preaching was kept on a leash; it never impeded the narrative flow, never got in the way of a gripping story that I just had to finish, a story filled with fresh, funny characters who became my friends. And anyway, when you’re young, you don’t mind listening to a short sermon or two; you desperately want to find out how the world works, and this man came across as someone who knew. Certainly, no other writer gave me that wonderful “the future is now” feeling like Robert A. Heinlein did.

The adult novels of the 50′s (Double Star, The Door into Summer, The Puppet Masters) are also extremely well-made and entertaining, but as the 60′s progressed the tone of the lectures became increasingly hectoring, and they started to expand until they overwhelmed the stories. By the time the 70’s rolled around the books had thickened (or curdled) and became, for me at least, unreadable. (I very rarely give up on books, but for the past forty years my bookmark has been frozen on page one hundred sixty something of I Will Fear No Evil and I expect it will remain there for the duration, especially since I already peeked at the last chapter and know how it ends.)

What makes Heinlein such a problematic and yet still vital writer is that his virtues and vices are so mixed, as I realized anew when I started writing this essay; it was impossible to think of one of his virtues without a corresponding vice instantly coming to mind, and vice-versa. If his work were all of a piece, he would be easier to judge, but it’s the conflict between his empathy and humanity and vision on the one hand and his callousness and solipsistic selfishness and inflexible certainty on the other that gives his work a real creative tension. When the balance lurches too far in the wrong direction, however, the result can be ugly — morally and aesthetically.

The hinge that Heinlein’s career turned upon and the point where the balance decisively shifted for the worse was, as I’ve already implied, his 1961 Hugo Award winning novel, Stranger in a Strange Land. There was some bad Heinlein before that and some good Heinlein after, but Stranger is the line of demarcation between the writer and the Oracle. (The last thing he wrote where the elements were in anything resembling balance was The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, but there are still a lot of people who can’t read that book, though I do like it.) Despite an intriguing premise and some rousing scenes, Stranger in a Strange Land is the point where telling a story took a back seat to pontificating from the balcony, and story never got its hands on the wheel again, or not completely.

That was a genuine loss, because at his best, Heinlein told stories that really moved. In Have Space Suit, Will Travel (for my money his best book) the teenage protagonist Kip Russell can barely turn around twice before he jumps from earth to the moon to Pluto to Vega to a planet out of the galaxy altogether, somewhere in the Lesser Magellanic Cloud, dodging ruthless alien space pirates all the way, and finishing by standing in front of a galactic court, pleading for the life of the human race, which the court is considering terminating — the human species may be too dangerous and unpredictable to be allowed to exist. (If you can resist jumping up and down and cheering during that scene, at least internally, I’ll drop you from my Christmas card list; you’re not worth the stamp.) The story is intensely dramatic and exciting (and funny), and most of all, it never slows down or loses its forward momentum. At the top of his form, Heinlein had his foot on the gas every minute, and if he indulged in the occasional aside along the way, you didn’t mind because you knew you were going somewhere.

As a social prophet, Heinlein is often startlingly prescient, though like the rest of us lesser mortals, he is often both right and wrong. His views on sexual mores and practices are a case in point. He would be completely unsurprised by marriage equality, and when group marriages are recognized (as they inevitably will be) he again wouldn’t bat an eye. He predicted these things in the Eisenhower 50’s, when they were not a part of anyone else’s futures.

At the same time, though, his view of sex as a weightless act with no more moral or social significance than brushing your teeth is sheer fantasy. The depictions of utterly frictionless sexual relationships in his later books make you wonder if he ever knew any actual men and women. (And sex in his books is so boring; reducing the act to something that has no more meaning than trimming your toenails means that every time he goes on at length about sex, it’s as engaging as reading eight pages about… trimming your toenails.)

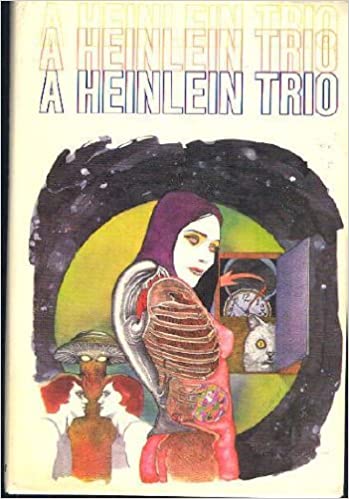

Heinlein’s highs and lows over a long career make it especially important to seek out his best books (and he wrote an armload of great ones), but when I go to the local chain, it baffles and infuriates me to see that it’s the latter, bloated, ossified tomes that are mostly on the shelves. People tell me they don’t like Heinlein and I ask what they’ve read (or tried to read) — The Number of the Beast?! Oh my God! Judgements about writers should be based on their strongest work, and that’s hard to do if Barnes and Noble only stocks The Cat Who Walks Through Walls or To Sail Beyond the Sunset. For anyone who wants to sample him at his peak, I would suggest A Heinlein Trio, which collects his three best novels of the 50’s — the aforementioned The Puppet Masters, Double Star, and The Door into Summer. The first is a bloodcurdling tale of an invasion by mind-controlling alien slugs, the second a Machiavellian yarn of high stakes galactic politics, and the third an ingenious time travel story with surprising emotional depth.

The Trio was published a long time ago by the Science Fiction Book Club, but it’s still easily obtainable from all the usual suspects (or you could just buy the three novels individually — The Puppet Masters seems to be the only one that’s currently out of print).

I would also add a “juvenile trio” — my choices would be Red Planet, Space Cadet, and Have Space Suit, Will Travel. If you can read those six books (and all six together are shorter than many of today’s doorstoppers) without being enthralled and entertained and delighted (and sometimes angered or put off — they all contain elements of Heinlein at his worst, too) then you are to be commended; you have an extraordinary resistance to the skills of someone who was, at his best, one of the all-time great science fiction storytellers.

Robert A. Heinlein has to be read, he has to be remembered and honored — but certainly not uncritically. There are books of his that I would under no circumstances part with, because of their drive, inventiveness, and brave, buoyant joy in drawing aside the curtain that conceals the future, a future that will be more amazing than we can imagine, a future that we can master by thinking and acting without fear, with confidence in our best selves — the books I’ve already mentioned plus Citizen of the Galaxy, Farmer in the Sky, Glory Road, The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag (a dark fantasy in a class by itself in Heinlein’s work, a metaphysical nightmare as brilliant and terrifying as Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday), and many more… and just as many more that are capsized by his preachiness, pontifical certainty, wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing sexism, and arrogant, unfeeling indifference to human weakness. Whichever side of the line you come down on — or if you find yourself straddling it like I do — the one thing you can’t do is pretend that he is a negligible writer without continuing value or significance. How many writers can still start a pro-con knock down-drag out fight almost a century after they first appeared on the scene?

In his prime, Heinlein’s pied-piper narrative voice carried all before it, sometimes even to the point of obscuring what he was actually saying. Because he can so easily disarm you with his brash charm, he’s a writer you can never drop your guard with; you always have to keep him in front of you. Infuriating, innovative, divisive, inspiring, contentious, courageous, dangerous, bafflingly obtuse and astonishingly prescient, Robert A. Heinlein, a writer of undeniable virtues and inexcusable defects, is just as essential now as he ever was. I’m sure he’d rather be remembered for his faults than not be remembered at all, but I find that when all the evidence is weighed, I’m inclined to be more generous in my judgment than that.

So… what’s your verdict?

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a review of Arch Oboler’s Drop Dead! or Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Chicken Heart that Devoured the World but Were Afraid to Ask

I’ve read almost all he wrote up to and including Starship Troopers, except most of the juveniles which I regret never having access to when I was a kid.

So I have mostly a positive impression of him so far, but I understand he was a…complex man.

Two things that had a big impact on him was first (if I remember the details correctly) as a kid witnessing a hobo getting killed trying to save a woman on a rail road track, and the second was the story of infantryman Rodger Young getting killed in WW2 after taking out out by a Japanese machine gun nest, saving his platoon.

But I guess he was bigger on sacrifice than compassion.

Most of his female characters are obviously based on his wife Virginia.

So from what I’ve read so far, I think his main flaw was the samey characters; nearly always The Competent Man (or Boy) and the Ginny female. So while Heinlein himself was a complex man, it’s not reflected much in his characters.

But as I read more of Heinlein, I’m sure the preaching is what will eventually turn me off. I have low tolerance for preaching.

Knut, you’re absolutely right about the sameness of RAH’s characters; the kind of people that he approves of are very narrowly defined, and they do indeed all sound alike…about like Heinlein himself sounded as he held forth in his living room, I expect. It can get wearying; reading a book of several hundred pages with dozens of character can leave you feeling like you’ve been pushed into a corner and harangued by a fanatic. I really noticed it when I reread Stranger in a Strange Land a few months ago in preparation for this piece.

I decided to give Heinlein another chance a few weeks ago and read ‘Door into Summer’ which I actually found pretty enjoyable. I reckon it had a lightness of touch which his anthology – ‘The Green Fields of Earth’ – lacked.

Your article reminded me of that old line – ‘I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him’ – inasmuch as a lot of the sins you ascribe to Heinlein are still very much prevalent (or were, until very recently) to the extent that they might not to be the real problem.The tendency of speculative fiction writers to get increasingly preachy (a lot chin-stroking, less and less action) has worked to the detriment of more than one fantasy trilogy.

And not just the preachiness!

‘A middle-aged male writer whose idea of a well-ordered world is apparently one in which an endless stream of beautiful, cheerfully compliant young women are sexually available to him on a no-obligation basis.’

The irony is that this was equally true of many authors of literary fiction up until ten years ago – e.g. Philip Roth regarded it as one of the perks of the job. “You used to be able to sleep with the girls in the old days,” he told Saul Bellow. “And now of course it’s impossible. You go to feminist prison; you serve 20 years to life.” Nice!

‘In any conflict between an individual and an organization, Heinlein is invariably on the side of the individual.’

Sure, but Heinlein doesn’t necessarily discount the importance of that organisation, the military being a case in point: his sympathies are with the grunts on the ground and not with the top brass, but this is still a guy who turns up for work every day, red tape notwithstanding. I did hear some apocryphal anecdote re Heinlein being unhappy with how Bradbury never served in the army (Bradbury was rejected because of his poor eyesight) which certainly – if true – doesn’t cast him in a very flattering light.

I think the problem might be more fundamental; Heinlein was a very relevant voice for his day. Shorn of that relevance he’s still a solid enough author, but maybe lacks the ‘oomph’ factor? Bradbury’s literary pyrotechnics (for example) will probably ensure he gets read and re-read.

I hadn’t heard of that Bradbury remark, Aonghus. I have to say it’s a low blow coming from someone who had to leave the service himself because of health problems.

I came across it in some article a few years back (I think!) but can’t find any evidence to support it online, other than a YouTube clip* in which Bradbury reveals that they made up after a five-year hiatus (he doesn’t clarify what they fell out over, though).

* SDCC 2006 – Ray Bradbury talking about Robert Heinlein

I agree. Heinlein got me into SF as a young teenager with Have Space Suit Will Travel, Tunnel in the Sky, Space Cadet, and Farmer in the Sky. I graduated to Stranger in a Strange Land, but found it difficult – but at the time there weren’t that many good adult SF writers out there. I struggled with Frank Herbert too. When I moved countries and had to leave 3/4 of my books behind, his adult books stayed behind. I did enjoy Starship Troopers and I thought that the ethics lessons were the most interesting, as it made me think and question my earlier ideas. The movie was terrible. Unpleasant Profession also very good. I did enjoy Number of The Beast, but to have to read Time Enough For Love and Stranger in a Strange Land to understand it. Yes as a young white male his adult books did not offend me at the time His sexual mores were ahead of his time, but the did not understand women at all, and could not write them. The world has changed so much now, for the better. He had his time and place, just like Enid Blyton, but there are much better adult SF novelists now.

I will confess that my best friend in childhood was a Heinlein addict. (What was the best Heinlein? The latest one that he had read.) So, I read a lot of loaned Heinlein, not many of which stuck with me. Perhaps his best work was at shorter lengths, though the later weird reproductive vibes show up early (“By His Bootstraps”, 1941).

But it would be good to keep some portion of his works in print, if only to continue my favorite sf convention game of asking aloud, “So, what was the last good Heinlein?” and then duck. (And, yes, my answer is usually Moon is a Harsh Mistress).

If you need a writer to conform to – or at least not clash with your beliefs and values… And I extrapolate want the story to conform also… Well, why read anything at all? It either expresses the ‘correct’ dogma 100% but is a waste of money and time since you know it already – or it’s not 100% and is a crime anyone is allowed to be published or sell it and if you read it woe to you – especially if some tiny idea slips through and might plant a seed that changes your mind or gives you a new idea someday. Personally I care if they make a good story and if it’s crazy and pulls the rug out it’s a matter of it being a good enough story to do that.

Heinlein was a great writer. Sure he had some strong beliefs and quirks, some things that offended people then and especially now. GOOD. I have a hypothesis that its some kind of cruel cosmic rule that affects nearly every creative person in the arts (especially writers!) but also leaders, visionaries, philosophers, thinkers… They all have to have some kind of deep flaw, dark secret and or perversion that is usually unacceptable for their times or worse down the road. It’s part of that “inner pain” that causes them to inflict their frustration on the world that causes it – uh, write great works of literature for posterity. Really, anyone saying dismiss Heinlein over his sexist and militaristic but libertarian views that don’t “Grok” with today’s …whatever it is politics… – well they’d go to HPL for his racial views – and then they turn silent and run when you start to talk about L. Frank Baum – once they realize he wrote “the Wizard of Oz” which they didn’t before. Be funny to mention L. Frank Baum as “A Penny dreadful era author” and his views on Native Americans first and watch the …hyper progressives… shriek how he should be cancelled, his body exhumed and violated, then they realize he’s behind Wizard of Oz which most do love deeply…

I’m tempted to write a book on this subject all the “he did ….!!!???” of famous writers and others. It’d be 1000 pages easily, take a few years, but of all my writing ideas it’d likely sell very well if printed and on bookstore shelves. And – 5000 years hence the Cruel Emperor Tson Chon will find a copy (Holograph archive/computronium held scans) read the first dozen pages and go “Ah! This very wise! I add entire contents of book to banned literature section. Every book mentioned is horrific slow death to own or read. Author long dead, no need to eliminate? Good. He get note of honor for help to Emperor. This saves me much time…”

The ritualized cleansing of Heinlein…

its like a rite of passage…

happens every couple of months.

😉

What I find interesting, is that in SF it is always Heinlein…

And Its nearly always the same…his characters are one dimensional…his women are unrealistic male-gaze fantasies…His plots are jingoistic…his later works are all trash…he was an evil patriotic militaristic libertarian fascist…etc.

I cant really think of a time anyone has ever taken the fine tooth comb to the oeuvres, personal lives, and beliefs, of, lets say, Asimov or Clarke (to name the other two most listed as the mythical “Big 3” of SF) in the same way they do Heinlein. The other two, if they are ever mentioned, get glowing posts about how great and far thinking they are, sure it might be mentioned as an aside that Asimov was handsy at times…but rarely actual critical examinations of the works and the person behind the work.

Ive come to think it is a measure of how important, even over the protestations of themselves and the rest of the Sci-fi Intelligentsia, they still find Heinlein, how afraid they are of him and what he said in his works, or maybe just as importantly, what they fear they would find if they took the same critical, and thorough, examination of the works and personal lives of the others, those the SF-Intelligentsia zeitgeist decided arent infested with wrongthink..

I like Heinlein’s stories, I like them still and I feel no guilt or remorse over that. Recently I listened to Citizen of the Galaxy on Audible. I enjoyed the stories but that is all they are, stories. Heinlein himself, I do not know. I never met him.

I always saw Citizen as a space opera spin on Rudyard Kipling’s “Kim” particularly the first part. And I think Heinlein and Kipling would have gotten along quite well.

The earlier books I probably enjoyed more as a less knowledgeable teenager than I would know if I’d reread them. His (as you aptly describe) ‘goatishness’ make books like “Friday” unreadable. Those ‘liberated’ ideas of teenagers throwing themselves at their grandfathers (but they’re young, and hot) make these books ‘sticky’. I’d say the male figures in these are sock puppets, but that puts even more unfortunate images in my head!…

If that is the way it works, maybe it is good that Ian Banks passed on before the serial killing and genocide started.

We had a discussion about your post over in a FB group. https://www.facebook.com/groups/244104312868805/posts/895652984380598/.

Unsurprisingly, most of the women agreed with you, including Heinlein’s inability to write a female character without including the tropes in Friday (spoiler) rape – relax and pretend to enjoy it, rapist can’t help himself, and in the end – woman marrying rapist and becoming a housewife nonsense. A real disappointment, since there were some great ideas and he could’ve done so much better with the story.

His adult books are mostly overwritten, terrible characterizations of women, unrealistic views of sex and women, and lord, where was the editor??? The juveniles are much better (excluding Podkayne of Mars).

Thanks!

I’m flattered! I think a lot of RAH’s difficulties – especially with women – are founded in his solipsism, a word I used two or three times but could have used twenty or thirty. It’s why all of his characters sound alike. He couldn’t imagine genuinely different people; at bottom he didn’t really believe in the existence of anyone but himself.

Or maybe like too many other writers his protagonists are idealized versions of himself, with all his strengths, but none of his weaknesses. And in addition they can live out their fantasies (especially sexual ones) through their characters.

But then Heinlein’s stories are usually more about ideas than people (at least the older ones), so his samey characters doen’t hurt his stories as much as it would have more character driven stories.

And as with Lovecraft, I can’t help wondering how many read Heinlein now just to find some character flaws they can virtue signal, instead of just enjoying their stories, or just stop reading them if they don’t like them.

Point taken, Knut. But I do think that there is a strong strain of genuine “I am the only one in the universe” solipsism in RAH, of the kind seen in Mark Twain’s The Mysterious Stranger. You can see it most strongly in All You Zombies, The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag, and especially I Will Fear No Evil, with its incestuous family that ultimately melts into one homogenous consciousness.

He also explored the topic most obviously early in his career in “They”. I haven’t really though of solipsism as a “strain” in Heinlein before, just as one of many thing that interested him.

I shudded at the description of “I Will Fear No Evil”, though.

Hard to get more solipsistic than “–All You Zombies–“, where the protagonist is his own mother and father and daughter. Follow those genetics, if you can!

You are certainly creative in interpretation of a time travel gimmick like All You Zombies. In fact, I think all the stories you mention are examples of playing with the unexpected consequences of time travel or advanced technology or both and coming up with an original idea. Too much navel gazing?

[…] August 16, 2021: Here’s an interesting essay by Thomas Parker at the Black Gate, My Robert A. Heinlein Problem, strongly recommended for your […]

So.. he was human, imperfect and impure like the rest of us.

After coming across a link to your site in the FB Heinlein forum, and reading it, I have to say that I agree with much of what you’ve said.

When I was 7 (or so), my mother used to sneak me into the adult section of the public library (kids were NOT allowed) and check out books I had chosen for me. There, I discovered RAH and science fiction and am still a voracious reader of the SF/fantasy genre after 65+ years. Heinlein may have been my first, but by no means my last SF author to love.

Now, to a few of the books. I found Stranger in a Strange Land nearly unreadable, and this was as a young-ish adult. There are a few other books that left me with the same reaction when I finished them: “I struggled through all of that for this ending?! UGH!!” Gone With The Wind comes to mind.

Overall, I think Time Enough for Love is my all time favorite, but Methuselah’s Children, The Door Into Summer, Tunnel In The Sky, and Have Space Suit, Will Travel are all close competitors. Frankly, I’ve read so many of his works that any that stand out in my mind must have been either fantastic or truly horrible. The titles have begun to run together in my brain.

As to the author himself? He was a product of the time and society in which he was raised and lived. When I was much younger ( being born in the late 40s), nothing about his writing seemed particularly odd to me. As a grown woman, one who has worked in several male-dominated industries/jobs, I can recognize that many of his viewpoints don’t jibe with my own, but I’m not going to denigrate him for that, it’s not worth my time. The fact that I thought he still told a good story (and isn’t that what we really want when we read a book?) was worth the minor annoyances of a stale view of feminine independence, or lack thereof.

So yeah, I will probably reread some of his books again, and I will probably love them again. I will continue to read the new authors as well as the the other stars in that pantheon: Asimov, Bradbury, Clarke, Blish, et al.

Read or listened to every thing up to “I Will Fear No Evil” so far. The plots are better in the juveniles and early stuff. More actual events that are possible to follow. Less interior monologue. As for prescience, nothing beats Heinlein’s ‘prediction’ that Hitler would shoot himself through the roof of the mouth rather than surrender.

RAH wrote this in 1938 in his first and long-time unpublished novel, “For Us, the Living: A Comedy of Customs” which also lays out much of the path of his ‘Future History’ novels.

It’s generally agreed that later Heinlein suffered from a lack of an editor (in addition to, for a while, lack of oxygen to the brain);

However, to borrow an RAH phrase, deponent sayeth not, or at least no more at this juncture and I have read the Patterson bio, the Panshin critique, explanations and apologetics from people who were in the room and am currently working through The Pleasant Profession of Robert A. Heinlein by Farah Mendlesohn and find that I have issues with critique regarding this author that does not take a very deep dive. For quick surface analysis, I’ve my own piece – Robert A. Heinlein was a Dick to reference https://amazingstories.com/2014/06/review-robert-heinlein-dick-review-pattersons-bio-volume-2/

Interesting. A couple things, he wasn’t a WWII generation guy. He was 1930’s and a career Navy man. He was more a contemporary of E.E. Smith than the later golden age writers. And the pet names for the women like Angel or Glamour-puss or Doll, were SOP for all Radio detective and spy shows of the 1940’s 50’s and early 60’s.

I am surprised for your disgust at lack of displayed compassion by The Competent Man and how a view of life that disagrees with your own you see as unethical. The Competent Man in his stories is faced with situations with no room for compassion. He basically deals with life-boat ethics at every turn. The Competent Man is rational.

Spacesuit was number one for me when it was in my middle school library – maybe 6th grade too – and my favorites were probably also Tunnel in the Sky and Time for the Stars (though on re-reading Time for the Stars I found it rather depressing as an adult).

I will say the flaw in your thesis is that in many of his stories the main character begins as a failure and BECOMES The Competent Man through several trials in a hero’s journey.

If you see these traits of Heinlein as flaws, what did you think of Gravity’s Rainbow?

Clearly you feel that I was too hard on RAH, as is your right. I was more worried that people would think I was being too easy on him! (As for Pynchon, I found V. such a slog that I’ve always shied away from Gravity’s rainbow. Why go looking for trouble?)

[…] Problems with RAH […]

I’ll add one more item to the case for the defense: When Philip K. Dick was in need, Heinlein stepped up, gave him what he needed without expectation of recompense. In PKD’s words, “Several years ago, when I was ill, [Robert A.] Heinlein offered his help, anything he could do, and we had never met; he would phone me to cheer me up and see how I was doing. He wanted to buy me an electric typewriter, God bless him—one of the few true gentlemen in this world. I don’t agree with any ideas he puts forth in his writing, but that is neither here nor there. One time when I owed the IRS a lot of money and couldn’t raise it, Heinlein loaned the money to me. I think a great deal of him and his wife; I dedicated a book to them in appreciation. Robert Heinlein is a fine-looking man, very impressive and very military in stance; you can tell he has a military background, even to the haircut. He knows I’m a flipped-out freak and still he helped me and my wife when we were in trouble. That is the best in humanity, there; that is who and what I love.”

That’s a great story – thanks for sharing it. It says a lot for a man when someone who shares none of his political or social views thinks so well of him.

Was there some creepy old man book he wrote about people mind melding? I recall reading something of his and deciding “never again.”

‘I Will Fear No Evil’…Interesting but not the greatest…The conceit of this story is not telling the reader that the rich man’s secretary is Black.

The story on that is a little more complex: Heinlein wrote the story with pictures of a nude White woman and a nude Black woman in front of him. His intent (the pictures were reminders) was to never let the reader be sure of Eunice’s race.

Yep – I Will Fear No Evil. Definitely RAH well on the way to total ossification.

Perhaps the titles ‘always on’ the B&N shelves are because the other better stories have been sold…I’m an big Heinlein fan even though his prediliction to scantily clad women with large breasts who nearly always seem to be ready for some not discriminatory mating can be a bit much…

The lessons of self-reliance and personal responsibility are good ones to learn. He writes from his times – He started the Naval Academy in 1925 and finally succumbed to one of the many illnesses that plagued his last decade on earth in 1988. That’s an awful long road to work through.

I’d love to learn more – yeah, I’ve read the Patterson bio – about how we got from near socialist utilitarian – RAH worked for the Upton Sinclair campaign for governor of California (EPIC) – to more or less anti-Communist hard case politics – He and Ginny did a lot of work for Goldwater.

Why would you recommend Space Cadet? Nothing happens until the end, and by then it is too little too late. New Heinlein readers should start with his best juvies: Citizen of the Galaxy, The Star Beast, and yes, Have Space Suit—Will Travel. Job: A comedy of Justice is an underrated late Heinlein book that gets overlooked to often.

I guess I recommended Space cadet because I like it, though to be honest, I haven’t read it in a loooog time. Back in the day, my most reread Heinlein was Space Suit, very closely followed by The Rolling Stones and Red Planet. I also have a soft spot for Tunnel in the Sky.

This was a truly interesting piece to read (mostly the piece itself, but partly the comments too), especially given the proposition of exiling the entirety of an author and the author’s body of work or not. I was glad to read at the end that the judgment fell more generously than that.

Heinlein is one where I find myself more inclined to banish the people who judge him (whether to lionize or to brutalize) than the author himself. Some of his work I love, and some of his work I detest– never to be read again– but the people who caused me to read the work draw my ire more than the author who wrote it, because they knew what they had read and did not give me a clear picture of the book they inflicted on me, just all of what they loved or all of what they hated. Cases in point:

–“Starship Troopers” was undergoing something of a Renaissance of interest when I first read it. A movie or something had come out, and my peers and role models were going wild over the book, giving it nothing but praise. When I read said hyped book, I found the story somewhat insipid, the characters’ actions often questionable, and the format very preachy. When I asked the people who had recommended it to me about how they had felt about X, Y, or Z events that I had had trouble with, they gave me blank looks. Then they insisted that I read some Orson Scott Card as well, but flatly refused to read the John Steakley I recommended. So the most charitable thing I could think about the people who subjected me to the book was that they were “trend” readers. I don’t think I ever listened to their reading recommendations again.

–“Stranger in a Strange Land” was required reading for a college course examining technical communication in science fiction. Most of the other reading (such as Bester’s “The Demolished Man,” Cherryh’s “Downbelow Station,” Gaiman’s “Neverwhere,” Asimov’s “Caves of Steel,” and even Herbert’s perennially awful “Dune”) had a lot of pockets of technical communication in them. SiaSL had vanishingly few. It came out over the course of discussion that the professor had chosen the book because she felt like she was part of the in-crowd when it came to grokking things, she enjoyed poking fun at Christians as closet cannibals, and the women exercising their freedom to be sexually available without attachments matched her definitions of female liberation. I found the story to be a massive stretch that wrecked suspension of disbelief regularly, and I mostly read it to see if we’d learn more about the profession of that certified witness/observer/judge character. The professor’s syllabus treatment of SiaSL hinted nothing of the themes we would encounter, and only lauded it as an award-winning classic that everyone should read at least once. She dropped severely in my estimation after SiaSL.

Was I mad at Heinlein for writing such underwhelming work? No. I was impressed that he’d managed to get it published and had drawn so much acclaim with it, and I resolved not to read those works again. I exiled the works, not the author.

A Heinlein that I loved was “Have Spacesuit, Will Travel.” That might have been my very first Heinlein encounter, actually. Since I’d already read a lot of more modern sci-fi, I recognized a lack of richness, where the characters’ personalities were concerned, but the adventure was phenomenal! The only thing that has kept me from re-reading it is the Kewpie Soap television special; the main character’s embarrassment and helplessness afterward cause a visceral reaction, even in memory.

Did I decide that Heinlein is an amazing fellow who is beyond reproach, because he wrote HSWT? No, even young me was not that starry-eyed. But the book gets to hold happy space on my shelves, and I will recommend it to readers with points caveated.

Heinlein wrote what he wrote, some of it good, some of it bad. He doesn’t get exiled for it. The people who get exiled are the ones who praise him or a piece of his work intemperately and thereby cause me anger, boredom, or suffering. The people who get exiled are those who criticize him without boundary, trying to make me drop even the works I know to be good. Neither of those sets of people will get my consideration for their literary recommendations ever again.

Verdict: Exile the false witnesses. Leave the accused to be himself.

I think that’s an excellent way to look at it. Some people (more and more, it seems) simply can’t accept that people and all that they produce are inevitably “mixed.” Purity, one way or the other, is the demand of the day. People are of course free to read any way they want to, and many select books “ideologically”, and read them the same way, afterwards issuing the appropriate praise and condemnations, but for myself, I just can’t do that. Heinlein is, for me, a test case – can you take the good with the bad, acknowledging and accepting (with a readerly acceptance) both?

Yes! Yes, you put your finger on it, exactly!

Since I apparently missed this one when it first dropped three years ago … Heinlein was one of my foundational authors, mostly because Dad had a pretty extensive collection of RAH paperbacks, which at some point ended up on my shelf. That pictured edition of Red Planet was the first Heinlein book I read (the summer after second grade, sitting out on the front porch, I read it cover-to-cover in one sitting IIRC) and that edition of Have Space Suit was the one I checked out from the library, and when I was growing up I read something close to everything he had written — I think I’ve never read his last book or two, which came out when I was a bit older, and by then even I knew that he had gone well and truly off of the deep end.

By coincidence, I just reread Rocket Ship Galileo for the first time in about 45 years — it was always my least-favorite of the juveniles, and the one I read the least back in the day; and rereading it today, I could kind of see why — it’s not a BAD book, but there’s also not a lot of there there, at least relative to some of the later, better books like Red Planet, Citizen of the Galaxy, or Space Cadet.

I agree that Rocket Ship Galileo is the weakest of the juveniles, and it was my least favorite, too. I believe it was the first YA that Heinlein wrote, so I guess he was still getting the hang of it. Have Space Suit and Red Planet were by far my favorites, with the Rolling Stones close behind.