Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: Rejecting Bushido (Part One)

Chushingura: The Loyal 47 Retainers (or 47 Samurai). Japan, 1962.

After militant nationalism in Japan during the Twenties and Thirties led to the disaster of the Forties, many Japanese blamed the country’s march to war on an excessive reverence for bushido, the samurai’s martial code of honor. Media that glorified Japan’s military history was prohibited during the American occupation, but in the 1950s movies and TV shows featuring heroic samurai began returning to the mainstream. However, a significant segment of Japan’s creative community regarded this as a woeful development, and nonconformists opposed to the innate conservatism of Japanese society began making alternative samurai films that, subtly at first and then openly, accused bushido culture of oppression and cruelty. Let’s take a look at how this played out on the screen starting with two films from 1962: Chushingura, which extols the virtues of samurai honor, and Harakiri, which is a virtual mirror image of the first, examining the same themes through a different lens and reaching diametrically opposite conclusions.

Chushingura: The Loyal 47 Retainers (or 47 Samurai)

Rating: ****

Origin: Japan, 1962

Director: Hiroshi Inagaki

Source: Image DVD

The tale of the 47 ronin is sometimes called Japan’s national epic, as it epitomizes the samurai virtues of courage and loyalty unto death. In Japan it’s been filmed at least six times, with countless other dramatic adaptations, but Inagaki’s sumptuous 1962 movie is probably the best-known retelling to Westerners. The film’s subtitle for its English language release was “The Loyal 47 Retainers,” but in the original Japanese version it’s “Story of Blossoms, Story of Snow.” Not blossoms as of budding flowers, but the fluttering petals whose day is over, and that fall as a harbinger of the death symbolized by the coming of snow.

The story is familiar: at the height of the Shogunate, a high-ranking samurai lord is preparing to receive a delegation from the emperor, and his ritual reception must be precise and perfect. It’s the job of Lord Kira (Chucha Ishikawa) to instruct Lord Asano (Yuzo Kayama) in the proper ceremonies, but the corrupt Kira is angry because the stiff-necked Asano refuses to grease the wheels with rich bribes. Certain that he’s untouchable, Kira repeatedly insults Asano, slapping his face with a fan, until Asano loses control and attacks Kira with a dagger right in the shogun’s palace. Kira is only scratched, but Asano is disgraced and ordered to commit ritual suicide, and his entire clan is disbanded.

That’s just the setup, the “Blossoms” part of the film. Next comes “Snow,” the plot of Asano’s now-masterless samurai to regain their warrior’s honor by taking the life of Lord Kira.

The first part of the film marches with a stately inevitability, as if every event is fated, the camera moving deliberately, almost majestically, except during the sudden chaos of Asano’s attack on Kira. In part two, the pace picks up: plans are laid and executed, spies lurk and are caught, and it’s all deceit and intrigue until the final paroxysm of violence, the raid of the 47 ronin on Lord Kira’s well-defended city estate.

This is a long movie, over three hours, and though it’s capped by a superbly orchestrated 20-minute orgy of vengeance, it takes its time getting there. The pleasures along the way include a gorgeous wide-screen re-creation of Japan at the turn of the 18th century and a number of fine performances by a first-rate cast. Of particular note are Matsumoto Koshiro as Chamberlain Oishi, who masterminds the Asano clan’s revenge while pretending to become a degenerate wastrel to conceal his plans, and Chusha Ichikawa, the weaselly face of despicable cowardice as Lord Kira. For those who insist that every samurai film should have Toshiro Mifune in it, he’s also here in a memorable supporting role as a powerful samurai-for-hire who holds off reinforcements while the Asano ronin hunt for Kira.

In short, which this movie isn’t, Chushingura is a visual feast for those who can be as patient for the climax as the Asano samurai. But it’s no dishonor if that’s not for you.

Harakiri (or Seppuku)

Rating: *****

Origin: Japan, 1962

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Source: Eureka! Blu-ray

This is a great film, but be warned: it’s as bleak as cold dry ashes, and while there’s some fine swordplay in it, it’s all in the last 20 minutes; the previous nearly two hours of talk and angry glaring serve as the grim setup to that socko ending.

The 1600 Battle of Sekigahara left Japan firmly under the control of the Tokugawa Shogunate, and with the land at peace, the ruling samurai class was left without a purpose. In the twenty years that followed a number of clans were dissolved, throwing many thousands of warriors out of work. By 1630 their plight was desperate, and in the capital of Edo some of them, faced with a life of ever-worsening poverty, chose instead to commit harakiri, ritual suicide. Harakiri was a feudal act that really needed to be carried out in a samurai lord’s courtyard, which was a nuisance for the clans of Edo. Some masterless samurai took to requesting to use a lord’s forecourt for harakiri in hopes of being fobbed off instead with a few coins and sent away. When one desperate young warrior approaches the Iyi clan with this scam in mind, the proud and cruel Iyi samurai insist he go through with the act — and when they find that his sword blades have been pawned and replaced with bamboo lathes, they force him to disembowel himself with his own dull wooden dagger.

The rest of the story details the vengeance taken on the Iyi by Tsugumo, the youth’s father-in-law (Tatsuya Nakadai, excellent as usual), another indigent samurai, but one driven to strike back at the Iyi even if it costs him his life. And he does this by strictly following the warrior’s code of bushido to trap the clan in a web of their own dishonor. This is not done as a celebration of bushido, but as an indictment.

Though its dark tone is unremitting, this is a beautiful film, masterfully composed. Unwavering in its conviction, it never strays into sentimentality. However, despite the top-notch fight scenes at the end, this is not a chambara adventure flick, so caveat emptor.

Three Outlaw Samurai

Rating: *****

Origin: Japan, 1964

Director: Hideo Gosha

Source: Criterion DVD

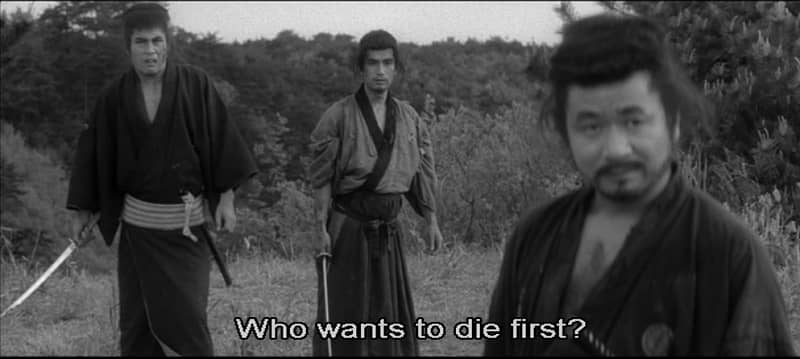

This is acclaimed director Hideo Gosha’s first feature after he cut his teeth directing shows such as the earlier Three Outlaw Samurai TV series, every episode of which is now lost, alas. This film serves as the origin story of how the three mismatched ronin came to be comrades of the road, and it is superb.

In a district with a corrupt magistrate (aren’t they all?) where the harvests have failed for several years running, some peasants, desperate for relief, have kidnapped the magistrate’s daughter to get him to present their petition to the clan lord. A roving samurai, Sakon Shiba (Tetsuro Tamba), stumbles on the mill where the three peasants are holding the daughter hostage, criticizes their amateurish efforts with an ironic smirk, but then, moved by their desperation, joins their cause. Shiba drives off the magistrate’s goons when they attack, so the officer orders his best hired samurai, Kikyo (Mikijiro Hira), along with a vagabond ronin released from jail, Sakura (Isamu Nagato), to handle the situation. Once he realizes what’s going on, the earthy Sakura switches sides to join the peasants, at which the effete Kikyo withdraws in disgust. The magistrate then sends Kikyo to collect the daughter of one of the rebellious peasants from a brothel to serve as a hostage to trade for his own daughter, and also hires twelve more scruffy ronin as hatchet men. Outnumbered, Shiba offers to turn himself in and release the magistrate’s daughter if the peasants are set free, and the magistrate accepts, pledging his samurai honor — but he’s a big fat liar, and Shiba is betrayed. This is too much for Kikyo: he goes over to the opposition, and then it’s three mismatched fighters against an entire clan.

After the disaster of blind bushido that was World War II, many samurai films were made about distinguishing honor from unquestioning loyalty, but Gosha takes it two steps further, decrying loyalty as a trap and honor as a figment. His three outlaws learn that, in a world of corruption and cowardice, they can be true to nothing but themselves and each other. Gosha’s direction is striking and dynamic, often in dark scenes carefully lit to highlight cruelty and danger, with more than a touch of film noir to them. The swordplay is exciting, just as choreographed as in a Kurosawa film but wilder and more naturalistic, and thus almost more convincing. Characterizations are strong, vivid, and conveyed in broad strokes, sudden closeups nailing home reaction shots to express violent emotion. The performances are strong, and the peasants and villains all get nuanced scenes, not just the samurai heroes. The twists and turns of the story play out with a sort of deadly inevitability, leading to a final confrontation with the clan’s famous leading swordsman, ultimately exposing the futility of the three outlaws’ effort to change the world they live in. It’s kind of a masterpiece.

Where can I watch these movies? I’m glad you asked! Many movies and TV shows are available on disk in DVD or Blu-ray formats, but nowadays we live in a new world of streaming services, more every month it seems. However, it can be hard to find what content will stream in your location, since the market is evolving and global services are a patchwork quilt of rights and availability. I recommend JustWatch.com, a search engine that scans streaming services to find the title of your choice. Give it a try. And if you have a better alternative, let us know.

The previous installments in the Cinema of Swords include:

The 7th Voyage and Its Children

The Good, the Bad, and Mifune

The First British Invasion

Wholesome Buccaneers (Pt. 1)

The Tale of Zatoichi

The Sign of the Z!

Gallic Gallantry

Classic, Mythic and Epic

The Exuberant Excess of Sixties Vikings

Tyrone’s Typecast Troubles

Not-So-Wholesome Buccaneers

Daimajin Strikes Again!

Three Counts of Monte Cristo

Mongols, Cossacks, And Tartars

I Heard You Like Swords

Bard’s Tales

Hu’s on First

Flynn’s Last Flourishes

Mighty Colossi And Hydrae

LAWRENCE ELLSWORTH is deep in his current mega-project, editing and translating new, contemporary English editions of all the works in Alexandre Dumas’s Musketeers Cycle, with the fifth volume, Between Two Kings, coming in July from Pegasus Books in the US and UK. His website is Swashbucklingadventure.net.

Ellsworth’s secret identity is game designer LAWRENCE SCHICK, who’s been designing role-playing games since the 1970s. He now lives in Dublin, Ireland, where he’s writing Dungeons & Dragons scenarios for Larian Studios’ Baldur’s Gate 3.

Thanks John! “Samurai Rebellion” will be covered in Rejecting Bushido, Part Two.

Thanks, Other John! “Sword of Doom” is another that will be covered in Rejecting Bushido, Part Two.

A great topic in a great series! I still remember the revelation of seeing Sanjuro on PBS back in the 70’s. The Three Outlaw Samurai is one of my all time favorites but I never knew it was a TV show. I too can’t wait to hear what you have to say about Sword of Doom.