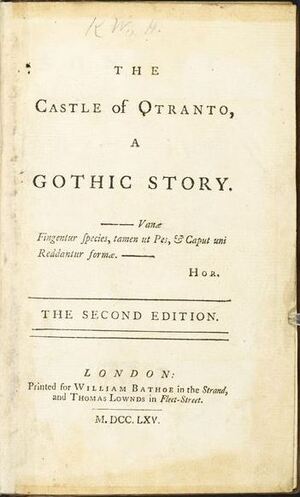

A Gothic Story: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole

The history of the novel in the West is long, complex, and complicated. Suffice it to say, by the middle of the 18th century the novel was a popular form of entertainment no longer confined to aristocratic readers. The romances of the Middle Ages and Renaissance had been largely supplanted by more realistic tales, but with the advent of Gothic literature, romantic fiction rose again in popularity, proceeding directly from Horace Walpole’s 1764 novel, The Castle of Otranto.

Gothic fiction is defined in the Encyclopedia Britannica as “European Romantic pseudomedieval fiction having a prevailing atmosphere of mystery and terror.” The deliberate admixture of realistic and fantastic elements in Otranto was a huge success. While Gothic fiction’s popularity has ebbed and flowed over the years, it has never receded completely. Horror fiction, as well as certain strains of romance and thriller writing, all trace their roots to this era.

Walpole was the youngest son of Sir Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, the first real prime minister of England. His time at Cambridge led to skepticism of certain aspects of Christianity, a strong dislike for superstition, and, in turn, the Catholic Church. Walpole was elected to Parliament multiple times from assorted rotten boroughs (electoral districts that had lost most of their populations but still sent an MP to the House of Commons — and which he never visited) and his father secured several adequately remunerative sinecures for him over the years. A Whig, Walpole opposed efforts he saw as supportive of making the monarchy more powerful. On the death of his nephew in 1791, at the age of 74, he became the 4th and final Earl of Orford.

He was described by contemporaries as effeminate and a bit of a dandy. The general consensus today is that he was asexual. He maintained a large correspondence with a great number of friends that has been called “an incomparable vision of England as it was in his day — London and Westminster with all their festivities and riots, the machinations of politicians and the turmoil of elections.” He coined the word serendipity, and is notable for an epigram opining “This world is a comedy to those that think, a tragedy to those that feel.”

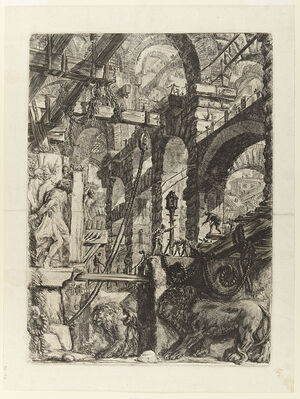

Walpole was a student and devotee of medieval history to the extent that, long before the Victorians’ fascination with the period, he built the first neo-Gothic mansion, Strawberry Hill House. He was also enchanted by the strange, imaginative architecture and etchings of Giambattista Piranesi, telling people:

‘This delicate redundance of ornament growing into our architecture might perhaps be checked, if our artists would study the sublime dreams of Piranesi, who seems to have conceived visions of Rome beyond what it boasted even in the meridian of its splendour. Savage as Salvator Rosa, fierce as Michel Angelo, and as exuberant as Rubens, he has imagined scenes that would startle geometry, and exhaust the Indies to realise. He piles palaces on bridges, and temples on palaces, and scales Heaven with mountains of edifices. Yet what taste in his boldness! What grandeur in his wildness! What labour and thought both in his rashness and details!’

He maintained a printing press in Strawberry Hill to publish other works, but not The Castle of Otranto. For that, he sought the services of others so the novel could be released anonymously.

The most interesting things about The Castle of Otranto are its two forewords; one from the first edition and one from the second. The novel itself, after a stunning start, rarely rouses itself afterward for any really frightening or exciting moments. The most memorable moments involve the dastardly Manfred’s frustration at dealing with the dimwitted servitors in the titular castle. The two forewords, though, are outstanding; the first being the creation of an elaborate hoax, the second, a statement of great artistic purpose.

Walpole’s book’s full title was The Castle of Otranto, A Story. Translated by William Marshal, Gent. From the Original Italian of Onuphrio Muralto, Canon of the Church of St. Nicholas at Otranto. The contention was that the book was really a long-lost manuscript detailing events set during the time of the Crusades. He provided such intricate detail that most readers were convinced of its absolute authenticity as an actual work out of the past and, possibly, even one that was based on real events.

The following work was found in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England. It was printed at Naples, in the black letter, in the year 1529. How much sooner it was written does not appear. The principal incidents are such as were believed in the darkest ages of Christianity; but the language and conduct have nothing that savours of barbarism. The style is of the purest Italian. If the story was written near the time when it is supposed to have happened, it must have been between 1095, the era of the first crusade, and 1243, the date of the last, or not long afterwards. There is no other circumstance in the work that can lead us to guess at the period in which the scene is laid; the names of the actors are evidently fictitious, and probably disguised on purpose; yet the Spanish names of the domestics seem to indicate, that this work was not composed until the establishment of the Arragonian kings in Naples had made Spanish appellations familiar in that country. The beauty of the diction, and the zeal of the author (moderated, however, by singular judgment), concur to make me think that the date of the composition was little antecedent to that of the impression. Letters were then in the most flourishing state in Italy, and contributed to dispel the empire of superstition, at that time so forcibly attacked by the reformers. It is not unlikely that an artful priest might endeavour to turn their own arms on the innovators; and might avail himself of his abilities as an author to confirm the populace in their ancient errors and superstitions. If this was his view, he has certainly acted with signal address. Such a work as the following would enslave a hundred vulgar minds beyond half the books of controversy that have been written from the days of Luther to the present hour.

Surely, it wasn’t the first literary hoax — there are ones dating back to Antiquity — and I can’t attest to how well done it was, but it worked. The public swallowed it all, making the book a huge success and indicating, quite emphatically, there was an appetite for such stories. It marked the beginning of a genre that would explode across the English-speaking world over the next several decades.

When the time came for a second edition, Walpole asked for his readers’ forgiveness and then explained just why he’d hoaxed them as he had.

THE FAVOURABLE manner in which this little piece has been received by the public, calls upon the author to explain the grounds on which he composed it. But, before he opens those motives, it is fit that he should ask pardon of his readers for having offered his work to them under the borrowed personage of a translator. As diffidence of his own abilities and the novelty of the attempt, were the sole inducements to assume the disguise, he flatters himself he shall appear excusable. He resigned the performance to the impartial judgement of the public; determined to let it perish in obscurity, if disproved; nor meaning to avow such a trifle, unless better judges should pronounce that he might own it without blush.

It was an attempt to blend the two kinds of romance, the ancient and the modern. In the former, all was imagination and improbability: in the latter, nature is always intended to be, and sometimes has been, copied with success. Invention has not been wanting; but the great resources of fancy have been dammed up, by a strict adherence to common life. But if, in the latter species, Nature has cramped imagination, she did but take her revenge, having been totally excluded from old romances. The actions, sentiments, and conversations, of the heroes and heroines of ancient days, were as unnatural as the machines employed to put them in motion.

The author of the following pages thought it possible to reconcile the two kinds. Desirous of leaving the powers of fancy at liberty to expatiate through the boundless realms of invention, and thence of creating more interesting situations, he wished to conduct the mortal agents in his drama according to the rules of probability; in short, to make them think, speak, and act, as it might be supposed mere men and women would do in extraordinary positions. He had observed, that, in all inspired writings, the personages under the dispensation of miracles, and witness to the most stupendous phenomena, never lose sight of their human character: whereas, in the productions of romantic story, an improbable event never fails to be attended by an absurd dialogue. The actors seem to lose their senses, the moment the laws of nature have lost their tone. As the public have applauded the attempt, the author must not say he was entirely unequal to the task he had undertaken: yet, if the new route he has struck out shall have paved a road for men of brighter talents, he shall own, with pleasure and modesty, that he was sensible the plan was capable of receiving greater embellishments than his imagination, or conduct of the passions, could bestow on it.

That is a stunning assertion of original artistic intent! Mixing the realism reigning in Enlightenment fiction with the myths and legends that same realism had seemed to banish, Walpole created an amalgam that would allow both to flourish. From Walpole to Stoker to King, the best horror succeeds because of its grounding in the real and tangible, and it would seem to begin here, in The Castle of Otranto. Within a few years, his literary manifesto was being picked up and unfurled by numerous other authors such as Clara Reeve, Anne Radcliffe, and William Beckford.

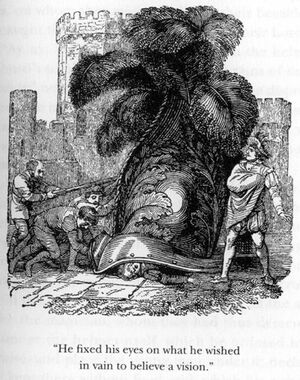

The novel tells the tale of Manfred, lord of Otranto, and his attempts to secure his domain for his family; a domain he has come by through less-than-scrupulous means. Manfred’s son, Conrad, about to be wed to the beautiful Isabella, is crushed by a giant helmet that falls without warning from the sky. Since a strange prophecy hangs over Otranto, Manfred decides he must marry Isabella himself in order to stave off his family’s doom.

“the castle and lordship of Otranto should pass from the present family, whenever the real owner should be grown too large to inhabit it“

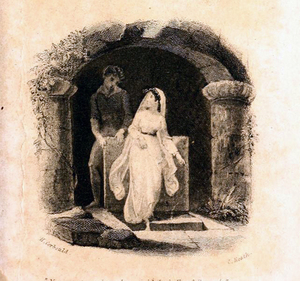

Castle follows Manfred’s assorted attempts to confine Isabella until his wife, Hippolita, accedes to a divorce. But Isabella is not one to sit back and give in to Manfred’s unseemly demands and makes every possible effort to hide from him. Along the way, she meets and is aided by a young stranger, introduced as a peasant drawn to the castle by rumors of the gigantic helmet. We come to know his name is Theodore, and eventually, he becomes the main protagonist, a man attempting to set his own path, but buffeted about by the winds of fate.

It’s difficult to pronounce judgment on a book that is so demonstrably important to the creation of a wholly new literary genre, but I shall nonetheless. The Castle of Otranto is not a particularly good book. Striven as he might to present the actions and personalities of his characters as realistic, far too much of the narrative is moved along by what seems an awful lot like chance. A character’s true identity is suddenly revealed because someone’s seen them in better light. Suddenly, a long-lost parent makes a reappearance from out of nowhere (twice!). Suddenly, a trap door is revealed. Suddenly, suddenly, suddenly. It’s enough to make a reader’s head spin. The story is complicated; it’s nonsensical, jumping about and around; numerous unforeseen twists occur; characters’ motives are suddenly (again!) revealed.

The spooky bits aren’t very spooky and are spread too illiberally through the novel for my tastes. Walpole might have appreciated a good fright, but he was far better at creating weird bits (again, too rare) that are genuinely fantastic. Halfway through the book, there is the procession of soldiers and servants bearing the ridiculously large weapon of the Knight of the Gigantic Saber. The best and most memorable moment is the sudden, deadly appearance of the titanic helmet, followed by the slow appearance of other parts of equally oversized armor.

“What are ye doing?” cried Manfred, wrathfully; “where is my son?”

A volley of voices replied, “Oh! my Lord! the Prince! the Prince! the helmet! the helmet!”

Shocked with these lamentable sounds, and dreading he knew not what, he advanced hastily, — but what a sight for a father’s eyes! — he beheld his child dashed to pieces, and almost buried under an enormous helmet, an hundred times more large than any casque ever made for human being, and shaded with a proportionable quantity of black feathers.

The horror of the spectacle, the ignorance of all around how this misfortune had happened, and above all, the tremendous phenomenon before him, took away the Prince’s speech. Yet his silence lasted longer than even grief could occasion. He fixed his eyes on what he wished in vain to believe a vision; and seemed less attentive to his loss, than buried in meditation on the stupendous object that had occasioned it. He touched, he examined the fatal casque; nor could even the bleeding mangled remains of the young Prince divert the eyes of Manfred from the portent before him.

There are some funny moments in The Castle of Otranto, mostly involving Manfred’s difficulties in communicating his purposes to his daughter’s dimwitted servant, Bianca. Sadly, it is not enough to make the book any better.

And still, I can’t help but recommend the book. Its significance to its own genre, to horror, to even fantasy, is undeniable. It is a foundational work from which later, better works were refined, and, at the very least, deserves to be read in that light. Horace Walpole was clearly a dreamer of elaborate and fantastical stuff and worked to put his ideas and images on paper for all the world to enjoy. That he did it imperfectly isn’t important, that he did it and inspired others is what matters. When he revealed that The Castle of Otranto was an elaborate hoax, the critics and public who had so praised the book turned on it, decrying it as superficial. It didn’t matter; Walpole had raised a flag that’s still followed loyally to this day.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

I read this many years ago and got some mild antiquarian enjoyment out of it, though a pulse-pounder it isn’t. On the other hand, Matthew Lewis’ The Monk, which I read a few years ago, is a real Gothic thrill ride. Its gleeful excesses would surely have given old Horace the vapors.

@Thomas – “mild antiquarian enjoyment” is perfect! I do plan to read The Monk, among others, later this year. I built a Gothic library (Vathek, Melmoth, Justified Sinner, etc.) twenty years ago, and I’m only getting to it now

I read Vathek a long time ago and remember almost nothing about it; Melmoth I’ve been warily circling for decades. My most valued gothic volumes are two big Penguin paperback anthologies that I got sometime in the 80’s – Great British Tales of Terror and Great Tales of Terror from Europe and America, both subtitled “Gothic Stories of Horror and Romance” and both edited by Peter Haining. They are long out of print but are well worth looking for.

This (and Melmoth and The Monk) have been on my list (and possibly now on my Kindle?) for years. Someday …

I have read Vathek a couple times, primarily by virtue of it being part of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. It was … fine?

As a college English prof too often stuck with basic & remedial courses, I got an occasional opportunity to teach a directed study — one-on-one — course of the student’s choice. A young man who knew of my interest in SF and Fantasy asked if I’d be interested in guiding him through a study of Horror fiction. Giving him an immediate and enthusiastic “Yes!”, I knew we’d have to start with Walpole’s “Otranto,” a novel I’d never read, but one of the perks of doing a directed study was getting to read material that was new to me as well as the student. I warned my eager student that I’d heard and read rather negative commentary on what is considered the very first Gothic novel, but I felt we owed it attention. It was every bit as bizarre and outlandish — perhaps even laughable — as I’d suspected, and I worried that my student might question my subsequent reading choices for the rest of the semester. Lewis’s “The Monk” was too lengthy for the time we had, and I had other novels I felt were crucial, so we went right into Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.” Poe came next, and I’d have liked to gone into Le Fanu’s “Camilla,” but I had to include Stoker’s “Dracula,” and we were ending with King’s “‘Salem’s Lot,” so we left Le Fanu and dozens of other seminal works for an “Essential Reading” list. We read several short ghost/horror stories — Edith Wharton, M. R. James, Jacobs’s “The Monkey’s Paw” — and several chillers by Lovecraft, an obvious candidate for the study, but my student hadn’t heard of Clark Ashton Smith, and I was anxious to get his reaction. I selected “The Empire of the Necromancers,” and it ended up being the student’s favorite story for the course. Finishing up with King was ideal, as the student hadn’t expected to consider it as classic as “Dracula.” In his course evaluation comments, the student admitted that Walpole’s novel had given him second thoughts about trusting my judgment, but the authors he’d not read before were a revelation, and he’d found Smith in particular delightfully grim. In my 31 years as a college prof, that directed study stands out as one of my best experiences.

Tell him to read Algis Budrys’s novella “Rogue Moon,” which is a science fictional haunted hosue story.

Don’t forget that any excursion into gothic territory should conclude with Jane Austen’s wonderful parody of the whole genre, Northanger Abbey.

Thomas, I think that’s the only Austen I haven’t read. Hard to picture her as a gothic explorer, parody or otherwise…

When I first read Austen (Sense and Sensibility, I think) what took me by surprise was how funny she is.

Yes! And even more so in “Pride and Prejudice.”

Dale, thanks for the tip! I have that in my basement somewhere; I’ll give it a read when I locate it, although I retired from teaching 4 1/2 years ago.

Cool post, Fletcher.

Who is the H.M. that wrote that intro?!

I’ve lived my life by Walpole’s quote of comedy and tragedy. Now I’ll have to read his book.

There’s an Otranto Place a few blocks from where I live in South Dublin, doubtless named after Walpole’s book, and every time I pass it I’m reminded that I never could get more than a quarter of the way into “Castle.” The Gothic still thrives: have you read Tamsyn Muir’s “Gideon the Ninth”?

I haven’t though it does sound wild.