A Year in Quarantine With the Criterion Channel

A year ago, a global pandemic forced me into quarantine. I don’t know what these last twelve months would’ve looked like without my subscription to the Criterion Channel. It wouldn’t be a catastrophe, of course — no worse than the actual catastrophe occurring outside my apartment walls. But the grind of dullness would’ve been far worse. I wouldn’t have the cinematic delights of dog revolutionaries, noir Westerns, a spiritual debate resolved in a gory barroom brawl, or a quality Christmas stalker film.

The Criterion Channel is the streaming version of the long-running Criterion Collection, the top name in cinephilia for more than three decades. I was a day-one adopter when the Channel went live in April 2019, and it’s the best investment I’ve made in any streaming service. It filled in the gap Netflix left behind when it abandoned its original purpose of offering movie lovers a place to find obscure titles and classic cinema and instead opted to become a content factory. I have nothing against new content — I’m glad to have the opportunity to see an innovative show like WandaVision — but only Criterion offers a special stew of cinema that appeals to me. I can discover film noirs, watch a surreal animated musical, trip out to a movie directed by Alfred Hitchcock’s credits designer about the evolution of super-ants, thrill to a Hungarian film about a militant uprising of shelter dogs, and watch back-to-back the 1946 and 1964 versions of Hemingway’s The Killers. Criterion Channel is a movie lover’s oasis, and during a year of being stuck at home, it was Athena’s greatest gift to me. I know Matthew David Surridge feels the same.

From March-to-March, I watched seventy-seven movies on Criterion Channel, along with various short films and special features. To mark this strange year of isolation, I’m taking stock of the best and most interesting of what I watched during “Anno Criterion.”

I can group the movies into three categories: fantastic rewatches, films I’ve always wanted to see before but which I didn’t have easy access to, and glorious discoveries.

“The Grand Revist” Movies

The Conformist (Il Conformista) is a good example of this category — a movie I haven’t seen in years that popped up on the Channel to demand I go back and spend quality time with it. The last time I’d watched Bernardo Bartolucci’s 1970 political drama about Mussolini’s Italy, I was seventeen and unprepared to absorb its oblique complexities. But its imagery stayed with me, since the photography by Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now, Last Tango in Paris, a dozen other visual masterpieces) is stellar even by his standards. Now I know enough of the political context of 1930s Italy to appreciate Storaro’s visuals as part of a horrific story about the psychological toll of fascism. The Conformist is still an oblique experience, not to mention a bleak one, but what a sensual marvel to behold.

Criterion often uploads films in curated collections. Their trilogy of films by Robert Siodmak took me back to my formative film noir years in college. I hadn’t watched these movies since I owned them on VHS in the late ‘90s: Phantom Lady (1944), The Killers (1946), and Criss Cross (1949). Siodmak was instrumental in the emerging style of film noir, and Phantom Lady is today recognized as one of the earliest classic noirs where all the elements were coming together. Bonus: it‘s based on a novel by Cornell Woolrich, a.k.a. my favorite writer. The Killers starts with a perfect twelve-minute adaptation of Hemingway’s short story. The rest of the film quite doesn’t reach this same level, but Siodmak was clearly turning into a great talent. Criss Cross is his masterpiece, and one of the quintessential noirs. All the elements are in place: Burt Lancaster as the doomed loser, Ava Gardner as the femme fatale, Dan Duryea as the sleazy villain (who’s also a doomed loser), a heist gone wrong, Los Angeles locations, and a Miklós Rózsa score. Criss Cross is peak film noir — there’s not much better than this.

Well … I could make an argument for Gun Crazy (1950), a couple-on-the-run thriller that was rediscovered in the 1970s when English-language film scholars began to recognize noir. When I posted on Facebook that I was rewatching Gun Crazy, author David J. Schow commented “ONE OF THE SEXIEST” and, yes, this is one of the steamiest crime dramas to somehow make it past the censors’ shears. It may have been the early ‘50s, but the torrid on-screen chemistry between Peggy Cummins and John Dall seems like it’s about to go X-Rated at any moment. Sex and violence at the movies is rarely so intoxicating.

When Criterion Channel uploaded a series of pre-Code Joan Blondell films, I thought the curators were just looking for an excuse to show The Public Enemy (1931). Whatever the motivation, I’ll seize any opportunity to watch Jimmy Cagney invent modern sound film acting in his first signature role as mobster Tom Powers. Although Cagney shoving a grapefruit into Mae Clark’s face is the film’s iconic image, I’d forgotten the most bonkers moment is when Tom Powers buys a racehorse he lost money on just so he can shoot it in “revenge.” Pre-Code Hollywood could be obscene, but in the best ways.

Criterion made a gloomy holiday season glow a touch brighter by making available director Bob Clark’s holiday classic … Black Christmas (1974). You thought I was going to say Christmas Story (1983), right? Sorry, I like my holiday films to bring me feelings of joy.

Honorable mention: Brute Force (1947); The Golem: How He Came Into the World (1920); The Eyes of Laura Mars (1978); The Naked City (1948); Beauty and the Beast (1946); Videodrome (1982); The Old Dark House (1932); What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962); Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954); The Lady Killers (1955), Rock ‘n’ Roll High School (1970).

“Finally Got to See” Movies

Criterion Channel explores movies across the complete spectrum of film history. But in two categories it’s served me particularly well: film noir and Westerns. I have long lists of obscure films in both groups I want to see, and the Channel continues to find them for me month after month.

One of the Channel’s inaugural collections was “Film Noir at Columbia,” and during the pandemic it brought that series back with even more films. The two that stood out of the films I’d not seen before are 5 Against the House (1955) and Shockproof (1949). Noir auteur Phil Karlson directed 5 Against the House, based on a novel by Jack “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” Finney, and it’s one of the strangest “heist” films I’ve ever seen. Five college students plan to rob a casino in Reno, not because they need the money, but as an academic experiment. Afterwards, they’ll give the money back and everything will be fine. Nothing can go wrong! This kind of story can write itself, but 5 Against the House finds the most interesting path to its finale through the character of Brick (Brian Keith), a PTSD-damaged Korean War vet who sends the “intellectual exercise” spiraling into a nightmare. Karlson directed better films (Kansas City Confidential, a personal favorite), but this is his most unusual take on a noir standard.

Shockproof has an odd pairing of director and writer that sounds like it’s the start of a joke. (“What if David Fincher directed a script by Tyler Perry?”) The director is Douglas Sirk, best known for his sentimental domestic melodramas. The screenwriter is Sam Fuller, best known for directing movies as if waging war. Shockproof has a rotten studio-enforced conclusion, but otherwise this Mutt-and-Jeff pairing of great talents is miraculously successful. Sirk was vastly underrated for years because of his association with commercial dramas, but he had an understanding of the power of taboo-breaking, and it served him well for realizing Fuller’s story about a parole officer who falls in love with one of his parolees.

Noir-related is the other version of The Killers (1964), directed by Don Siegel and starring Lee Marvin, and which Criterion made sure I could watch the moment I finished the 1946 original. The remake was intended originally as a TV movie but ended up going to theaters when the network turned it down. The flatness of the television format cannot damper this fantastic new take on the story, a rare remake that can justify its existence because it approaches the material from a completely different point of view — the POV of the killers of the title, who are no longer the anonymous dealers of fate but investigators into their own jobs. It’s a nasty piece of crime cinema that can stand tall among many of the giants of Siegel’s career. It’s also a rare case where watching the remake right after the original is not only not boring, it enhances both films.

You know what the weirdest thing I watched on Criterion this year was? Well, it was Videodrome, but I’ve seen that many times before. The runner-up is a film I’d waited years to get the chance to see: William Peter Blatty’s The Ninth Configuration (1980). Blatty is best known for writing the novel and later screenplay of an obscure work called The Exorcist. He directed only two movies in his career. I’m a fan of his second, The Exorcist III (1990), so I was curious about this Ninth Configuration business — especially since nobody could provide me an adequate synopsis of what it even is.

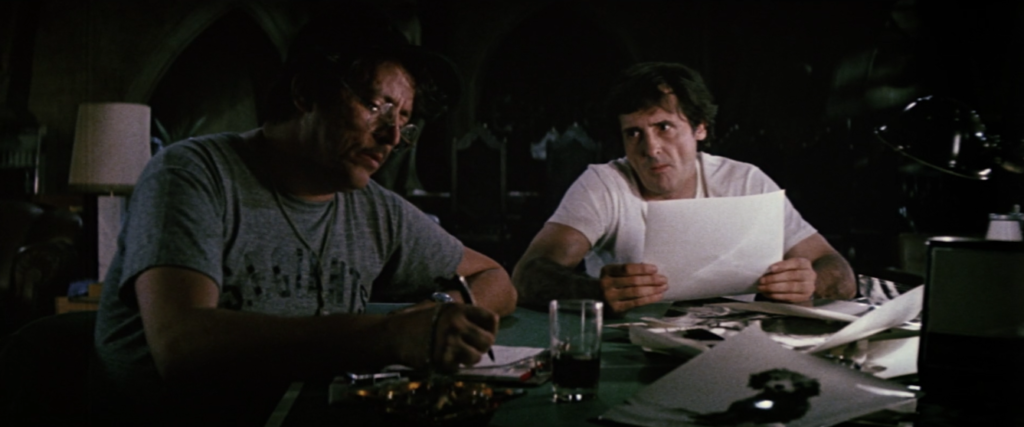

Now that I’ve seen The Ninth Configuration, I understand the struggle to categorize it. The film slowly reveals itself as a spiritual drama confronting that everlasting question of why a supposedly benevolent deity would permit human suffering and evil. To get there, the movie first passes through an ensemble comedy about a group of inmates at an insane asylum, then swerves into psychological thriller territory, and peaks with a bone-crunching barroom fight right out of the Incredible Hulk television show. You’re either sold on this film from that description or you aren’t, and either way, you’re right. I found myself enthralled with Blatty’s wit as a writer, his honest and deeply felt approach to the movie’s spiritual conflict, and his willingness to delve into bits of sheer oddness like Jason Miller recasting the plays of Shakespeare starring only dogs. (“Why are you teaching the dogs Shakespeare?” “Someone’s got to do it.”)

Two movies on the Channel drew me in because of their soundtracks: Seconds (1966) and It’s Alive (1974). I knew both because of their composers, who are the two cornerstones of my film music hobby. It’s Alive was one the last scores by Bernard Herrmann (Psycho, Citizen Kane, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad), and Seconds has an early score from Jerry Goldsmith (The Omen, Planet of the Apes, Chinatown). I’ll eventually see everything the two men scored — well, maybe not Mr. Baseball — and I came to these movies far too late for how good they are. It’s Alive is your standard killer-mutant baby movie, and it’s another one of those marvels from writer-director Larry Cohen (The Stuff, God Told Me To, Q: The Winged Serpent) where he takes the schlockiest premise and manages to mold a film that’s still schlocky but with thick layers of satire and smarts. These movies have no business being as good as they are, and It’s Alive balances its mutant baby with the right dose of paternal pathos. Cohen had a knack for finding underrated actors to anchor his movies: John P. Ryan (Runaway Train, Class of 1999) holds this crazy undertaking together as the father of the killer infant.

Seconds is a bummer. I watched quite a few dark movies on Criterion this year, but Seconds is unfiltered cinematic hopelessness. It’s a science-fiction fable about a man who gets a second chance at life and … sorry, no spoilers. You need to confront the slow futility of this journey for yourself. The movie has the finest performance I’ve seen from Rock Hudson, an actor who, in retrospect, was far superior to the reputation those light Doris Day comedies embalmed him in.

The pre-code Joan Blondell series may have only been an excuse to get The Public Enemy uploaded, but it allowed me to see Footlight Parade (1933), one of the pinnacles of the early ‘30s musical. I’m not the standard audience for movie musicals regardless of decade. But if you put Jimmy Cagney in it, firing zinger after zinger and reminding me why he may be my favorite actor of Hollywood’s Golden Age, I’ll watch your dang musical. I’ll probably love it. In fact, I did love it. It even has a number with dancing girls dressed up as cats that invalidates the existence of a certain other musical about dancing cats. I loved it, it was much better than Cats, I‘m going to see it again and again. (I know some of you out there got that. Hello, fellow Gen-Xers!)

Honorable mention: Ocean’s 11 (1960); Fun With Dick and Jane (1978); Lost in America (1985); The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945); The Awful Truth (1937); The Mouse That Roared (1959); You Only Live Once (1937).

“Where Has This Been All My Life?” Movies

Without question, the winner in this category is the 2014 Hungarian film White God (Feher Isten). I wasn’t completely unaware of the movie’s existence because I saw the trailers around the time of its theatrical release. It looked intriguing. Then I forgot about it. Now it’s one of my favorite films.

I’m an easy target for stories about girls who have beloved animal sidekicks — I wrote a whole novel about one of these pairs — so White God had a FastPass to my emotions. But the story of Lili, a lonely thirteen-year-old girl whose callous father forces her to abandon her dog Hagen into the city, is only the warmup for the magnificent final act: Rise of the Planet of the Dogs. Under Hagen’s leadership, the shelter mutts of Budapest break loose and form into a unified army that hammers bloody vengeance onto their human tormentors. It’s the dog lovers’ Spartacus, a canine charge of the Rohirrim at Minas Tirith, The Incredible Journey with mass casualties, Old Yeller if the dog shot first. I’ve never seen anything like it and cannot recommend it with more rabid (heh) enthusiasm. It checks off a set of boxes for me that won’t match everyone else’s taste, but I’m still making this a universal recommendation — not a step I take lightly.

Criterion’s “Western Noir” series was mostly films I’d seen (Man of the West, The Naked Spur, Day of the Outlaw), but 1949’s Lust for Gold was an enigma. Now I think it’s the most under-appreciated of the Western excursions into the noir style and deserving of as much attention as Pursued and Blood on the Moon. It’s intriguing because of its dual-time periods, with a hunt for missing gold unfolding in the modern (1940s) era as a framing device for the same hunt in the 1870s. The story could have worked if it were only set in the past, but the contemporary sections turn out to be much more than a framing device — the success of the movie hinges on how the boiling passion of a Western in the past erupts into a crime drama in the present. I also never get tired of seeing Will Geer, who in real life was a sweet and generous man, playing manipulative and heartless villains, something he also did in Seconds.

That I could call The Ninth Configuration the second strangest movie I saw on a list that includes Phase IV (1974) shows how unclassifiable that movie is. It‘s easily to classify Phase IV: an apocalyptic “revenge of the animals” science fiction movie, of which there were many during the 1970s. After that, nothing about Phase IV is easy. This tale about the emergence of super-intelligent ants in the Arizona desert has more in common with 2001: A Space Odyssey than Them! It unspools in hallucinogenic montages of the desert, close-ups of ant colonies, and alien sculptures erected by the super-insects who are moving toward a goal of re-engineering the human race as servants. This was the only movie directed by Saul Bass, a famous visual designer who made a mark on cinema with his posters and iconic credits sequences, most prominently for Hitchcock. I can’t imagine a world where Saul Bass would’ve gotten any further directorial work based on Phase IV, which understandably flopped, but at least he left us this gleaming ant monolith standing in the desert as a testimony to the breadth of his skill.

Did I ever have much interest in watching The Tune (1992) before this? I like animator Bill Plympton’s surreal short films, but I never thought about sitting through his first foray into feature animation. It feels like a connected series of short films (some segments were released as standalone shorts to help fund completion), but that matters not — The Tune is great. I don’t know why its soundtrack of comic music numbers hasn’t had more presence. “Lovesick Hotel” and “No-Nose Blues” need to find homes in actual stage musicals. (Not a stage version of The Tune however. That’s physically impossible. You might as well try to make stage versions of Bob Clampett cartoons.)

Honorable mention: Salome (1953); The Crowd Roars (1932); Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971); Sudden Fear (1952)

Oh, And I Watched Trog

Trog (1970) is terrible. Don’t bother. I’m certain a far better film starring Joan Crawford is streaming on the Criterion Channel right now. In fact, I just checked and there is: Sudden Fear (1952). A solid, over-heated noir thriller with a fun Jack Palance villain.

Ryan Harvey is the author of the novel Turn Over the Moon. He lives in Southern California where he studies Godzilla, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and for some unfathomable reason also performs improv comedy.

I’ve had the Criterion Channel for a year and a half. Best money I ever spent. I’m neck-deep in their “Japanese Noir” right now.

I won’t say the ONLY reason I signed up for Criterion was the HD streaming version of Thief of Bagdad; but it was certainly A reason.

Sure is nice to have, though, isn’t it? It’s one of the films that has always been on the Channel since it’s inception, and sits there in my library for whenever I want to watch it. It’s my equivalent of what Wizard of Oz is to everybody else.

Yeah, I love it very much and if it ever gets a physical Blu-ray release I’ll buy it in a heartbeat. And I’ve certainly seen plenty of other stuff since then that I probably wouldn’t have otherwise (in at least some cases as a direct result of your Facebook posts).

[…] “A Year in Quarantine With the Criterion Channel.” […]