Neverwhens, Where History and Fantasy Collide: Of Tudor Scum and Georgian-Gallants; an Interview with Peter McLean

My guest this month is Peter McLean, a successful short story writer and contemporary fantasy novelist who has cast his authorially eye on more traditional fantasy, with his War for the Rose Throne, series, the first two volumes of which (Priest of Bones and Priest of Lies) are now available, and currently in development for television by Heyday Productions. For those who may not have read them (and if that’s you, go do that now, we’ll wait) here is the bird’s view summary:

Tomas Piety was once a successful crime boss in the rough and tumble city of Ellinburg. Then came the War, which left its scars and also, ironically, his ordinance as a priest of Our Lady – not for any great change of faith, but because the unit needed a new cleric and Tomas could read. War-weary, the cynical priest heads home with Bloody Anne, his sergeant and confidant, to reclaim his streets. But rival gangs have carved up what was his and Ellinburg is collapsing from within. Tomas decides to reclaim what was his, with his new gang: the Pious Men. Unfortunately, there is more than just a few legs to be broken, as Tomas finds himself dragged into political and magical intrigue that extends well beyond the city.

The story is narrated by Tomas himself, and the limited viewpoint is used to great effect. We only see what Tomas sees, and while he is a mostly faithful narrator, there’s no doubt that he isn’t always entirely honest with himself, and there are times the reader is left sighing or shaking his head on Piety’s behalf.

Peter, for me, the series so far is a bit like Richard Sharpe meets Peaky Blinders, with a vigorous dose of old-school swashbucklers and maybe just a wink of your Warhammer origins for good measure. The result lives in an interesting, gritty, genre bending world that’s maybe the literary equivalent to Brotherhood of the Wolf. I love it! But those are my impressions; despite the time I spend writing Goodreads reviews, no one cares what I think. Was there a particular inspiration for you in creating Tomas Piety and his world? A particular theme or idea you wanted to explore?

I absolutely love gangster movies, and I love fantasy, and I just wanted to sort of mash the two together and see what happened. It’s the classic gangster story arc: working class kid takes up petty crime, progresses to organised crime, becomes successful and rich and powerful. And then… yeah. It usually all comes crashing down around his ears, doesn’t it? That or he ends up in politics.

Not only that, but I wanted to explore the effects of PTSD (or battle shock, as it’s called here), in a fantasy setting. So much fantasy is centred on “The Big War,” and I wanted to do something different. I wanted to show what happened after that war had been won, but show the effect it had on those who fought. Tolkien, himself a veteran of the Great War, did it at the end of The Lord of the Rings when Sam and Frodo return to the Shire, and that’s kind of what I was going for here too. War leaves lasting scars, and there is no happily ever after even for the victors. I’m not a military man but I know many people who have served and fought in wars, and I researched this very carefully. I think if you’re going to tackle a real-world issue in Fantasy then you owe it to those who have really been through it to portray it accurately to the best of your abilities

I love that idea, and I do see how Bones is a Scouring of the Shire, ala the Coreleonis! But it is also a very intimate story, of one man’s return from the wars, as you note. Did the story start with Tomas and work outwards, or did Tomas grow out of the larger story?

I always start with the character first. Once I have a character I use their personality and their background to begin to build the world that would have produced that person. Tomas is not particularly educated but he’s smart. He has a vicious streak, and can be quite ruthless, but he has his own moral code and lines he won’t cross. So why? What was his upbringing like, and what life experiences have made him the man he is? What sort of place did he grow up in, what has his life been like so far? That approach gave me the industrial grime and poverty of Ellinburg, and Tomas’ humble beginning as a bricklayer’s apprentice. He’s not a noble, or a farm boy who is the hidden bastard of a king. He’s just an ordinary commoner, a working class man, and I don’t think we see enough of those front and center in fantasy novels.

A column like this one is about “world-building”. For a history nerd like me, War for the Rose Throne really shouldn’t work!

Thus far, we’ve had two main settings: Ellinburg which seems quite happily rolling in the muck and grime of late Tudor England (16th century), and then the capital at Dannsburg, which has the elegance, costuming, politicking – even the tea trade — of Georgian England (18th century). Meanwhile, there’s no (little?) black-powder or tall ships but a big dash of some rather creepy magic. It shouldn’t work Peter! Yet it does. What were the rules or guidelines – small or large — you set for yourself to make Piety’s literary world feel “real” even though you were drawing from several different eras?

Oh sure, as a historical novel it would be a car crash but the joy of fantasy is that you can reshape the world to suit your storytelling needs. There is black powder, as Tomas refers to the cannon used in the war at Abingon, but we don’t have hand-held gunpowder weapons (yet). We have the tea trade with Alaria, but, as you say, no tall ships. That’s fine in this world, because Alaria isn’t as far away from Tomas’s country as India is from England. The technology level is generally Tudor across the board, but as you say in Dannsburg it feels like the Regency era. And that’s completely deliberate.

I think in fantasy you can get away with being period-fluid so long as it’s internally consistent, and more to the point that it resonates with the reader. I very purposely made Dannsburg feel different to Ellinburg, but it’s for societal rather than historical reasons. Everyone knows (or at least thinks they do) what the Regency period looks like, thanks to endless period dramas on TV. The Tudor grime of Ellinburg immediately implies poverty, horseshit and disease. I wanted Ellinburg to feel deprived, industrial and grimy. Even the war that Tomas and his crew have just returned from at the start of Priest of Bones, the first time these conscripted soldiers have ever experienced the noise and chaos of cannon and cavalry charges, is supposed to feel like the horrors of World War One.

So, to contrast the vast gulf between the rich and the poor that exists in this world, I wanted the lives of the rich and the political classes to look wildly different. I know what a noble Tudor banquet would have looked like, but it’s not honestly very appetizing to the modern eye and palate. More impactful then, I feel, to substitute a Georgian feast of dishes far more palatable to modern tastes. It’s about imparting a gut reaction more than anything else, about making the reader feel the difference rather than expecting them to know it.

It’s not even a location thing, it’s a class thing. In Priest of Lies when Tomas and Ailsa host a dinner party in Ellinburg for the city governor and wealthy people of business, it’s very much a Georgian dinner not a Tudor one. Tomas and his brother Jochan, being commoners, are quite happy with black bread and salt pork for breakfast while Ailsa wants and gets finer fare that simply didn’t exist in Tudor England. It’s about contrast and points of common reference, not history. It’s all stage dressing, drawing the reader into a state of mind and ultimately bringing them to a closer understanding of her character. Ultimately everything is about the characters.

|

|

US editions of Priest of Bones (2018) and Priest of Lies (2019). Ace Books, covers by Katie Anderson

That’s a really fascinating point and goes back to your first comment: your stories start with the characters and then ask “what world produced them?” From the point of creating audience “buy in,” what would say is most important in making readers believe and disappear into the world you’re are presenting? Is there something more (or less!) you’ve found fantasy requires?

I think, and I can only speak for myself as a reader and fan of the genre here, for me it’s always more about the characters than the world. When I’m reading I can be drawn in by well-drawn, sympathetic, interesting characters in a lightly sketched world far more than I’ll ever be by shallow, unengaging characters in a deeply imagined, detailed world. I remember I did a Q&A on Twitter a while back and someone asked me who was the worst monarch to ever sit the Rose Throne. How do I know? I don’t even know what the current queen’s name is, because Tomas doesn’t know and therefore neither does the reader. If it ever becomes relevant, I’ll think something up, but until then it just doesn’t matter. What matters for me is the characters, who they are and what they want, what their hopes and fears and dreams and relationships are.

In a sense, that feels me much like when we watch a play – the world is, of necessity, limited to a very narrow bandwidth of characters and situations. Yes, Henry V might have the Battle of Agincourt in it, but we have to perceive and experience it as vignettes because of the nature of a stage play, vs a film. It’s the intimate take.

All storytelling is about people at the end of the day, as far as I’m concerned. I’m far more interested in how Tomas feels about Ailsa, about whether he trusts the motives of the Queen’s Men and whether the Northern Sons will keep the peace than I am about the history of the royal family.

Let’s talk technology and magic. Your world draws from the “early modern” period, but the warcraft feels decidedly more on the late medieval end of things. Was downplaying gunnery intentional? If so, why?

Oh yes, completely. As I said above, I wanted the war in Abingon that Tomas has just returned from to feel like World War One, the first truly mechanized war. So yes, there are cannon, but this was our characters’ first exposure to them and the sheer noise and smoke and horror of them deployed on the battlefield. I can only imagine what the first experience of agrarian people pressed into fighting in wars with early cannon must have been, and it’s that same sort of shock and trauma that the veterans of the Great War went through that I’m trying to capture here. Without giving too much away, there are two books left to go and gunnery isn’t something I have forgotten.

Magic on the other hand…

Trying not to give away spoilers, but there is an official College of sorcerers in the kingdom, who are ostensibly very much of the scientific, Hermetic school and then there is the rather “wild” and sometimes terrifying magic of the Cunning Folk, the true depth of which we are still in the process of learning about. I found this building story interesting, both in terms of what you are creating for your story, but also as almost a meta look at modern fantasy, where there is a trend towards “Scientific magic,” whereas earlier fantasy often presents it much like we’ve thus seen of the Cunning Folk – magic is otherworldly, unpredictable and never comes cheap.

When I interviewed Christian (Miles) Cameron last year, we talked a little about “rationalizing” the existence of magic. For example, in his Masters and Mages, he concluded that if there was a systematic study of magic, and a number of female practitioners, they’d immediately want things like contraception and clean water. Starting from there he tried to think of how magic, in parallel to technology, would change a theoretical Renaissance Byzantium. Scott Oden took a very different tack, very much in the Sword & Sorcery vein – his magic is so wild and dangerous, there are few who can wield it reliably, so its immediate impact is powerful, but it’s change on his parallel history is minimal. What do you see as the role of magic in fantasy lit?

War for the Rose Throne, Book 3: Priest of Gallows, coming from Jo Fletcher Books

in the UK on May 27, and in the US from Quercus Publishing on April 29

Ah yes, there is the House of Magicians in Dannsburg, the arch-rivals of the House of Law. The Dannsburg magicians are very much modeled on the Tudor and later style of mysticism – they study the stars, debate philosophy and mathematics, and practice alchemy. There are strong historical precedents for all of these things. But define “magic”? Where is the boundary between magic and science, to a common people with very limited grasp of science?

On the other side of that coin is the cunning. Cunning folk are wild and often untutored, dangerous and unpredictable and persecuted. It’s a thing of instinct, and those who can do it often don’t know how or why they can. Witchcraft, some call that, but not all. It’s very tied in with the polytheistic religion of this world. When does prayer become miracle, miracle become magic, magic become witchcraft? That’s a question I don’t particularly want to try to answer. I think each reader will probably make up their own minds about that one.

Now, be honest… Grimdark is fairly low fantasy, as a rule, but have you ever found when you get stuck with a plot point it’s easy to say “because magic” to get out of it?

Oh, this is such an easy trap to fall into and I really try not to. In my books,- magic is a two-sided coin, either destructive or healing. In a way it fills the void of readily available black powder weapons as a ranged weapon, and in another it allows me a little leeway with what sort of wounds are survivable. Even so, the poor innkeeper who was stabbed in the thigh in Priest of Bones is still walking with a stick in Priest of Lies despite the life-saving ministrations of the cunning man. I don’t want magic to be a “get out of jail free” card, ever. That always feels like cheating to me. Violence should have consequences. I don’t like the sort of magic that lets you fight to the mortal wound and be good as new after a touch from your healer. That doesn’t work for me at all. If violence doesn’t have consequences, then violence will always be the answer and that’s boring, that’s video game stuff. Give me a reason to avoid a fight, to politic your way around the problem rather than shove a sword through it, and I’m immediately interested.

I’ll be honest though, I can’t bear “hard” magic systems, where every action and reaction is explained. That’s not magic to me, it’s science. I like to keep it mysterious, wild and unpredictable, but there have to be limits and there are always consequences. You’ll see an awful lot more about the consequences of unrestrained magic in Priest of Gallows.

Hmm… you may have just given a meta answer to your own question – “When does prayer become miracle, miracle become magic, magic become witchcraft?”: I don’t know, but once you can easily define, codify and predict its results, its science and no longer any of the above.

Coming back to the series itself, volume three, Priest of Gallows, releases soon, and from the teaser copy, I have a hunch we will start to see where the series title (War for the Rose Throne) comes in. Any teasers you are willing to share?

I have to be really careful here, but yeah. I guess all I’ll say about that is that there is more than one sort of war. By the time Priest of Crowns releases next year you’ll know exactly what I mean.

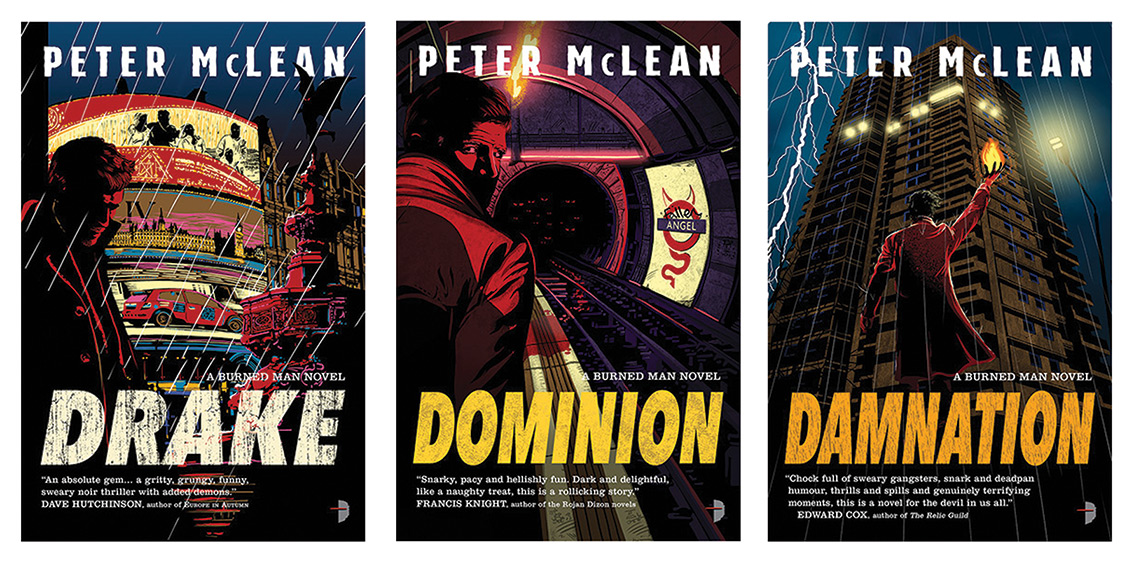

The Burned Man novels (Angry Robot, 2016-17)

Your previous series, The Burned Man, took place in contemporary London, albeit one with demons. Besides the fact that if you say “London, today” readers have an immediate image, rightly or wrongly, of the setting, would you say you’ve found it easier or harder writing in a secondary vs. a “magical primary” world?

I actually find secondary world much easier. Sure you have to make everything up, but the upside of that is that you get to make everything up! With something like The Burned Man I had to be so careful never to specify exactly where in South London we were, or I’d have someone on at me saying “but there isn’t a pub on that corner” or whatever. With secondary world it’s just how I say it is. It’s interesting that you bring up The Burned Man though, as I did the same period-fluid thing there as well, just to a lesser extent. It’s set in the “present day” (pre-Covid reality, anyway), but at the same time it kind of isn’t. Don Drake’s London exists in a sort of 1970s timewarp, with modern technology and conventions and diversity overlayed over the world of Callan and The Sweeny. Again, totally done on purpose.

You’ve also written Warhammer 40K novelettes. At this point, the literary world of 40K is enormous and ever-evolving, with an enormous fan base; it has to be a little daunting jumping in to those waters. Were you already a 40K nerd, or did you have to get up to speed?

I knew nothing about 40K when I took that gig. I’d seen the miniatures in the window of my local Warhammer shop but that was about it. I already had all of The Burned Man published by then, and I think Priest of Bones was either out or at least signed when I took my first 40K commission. I have to be honest, I did it for the beer money. It was fun though, and it was a good opportunity to work in a different genre and with some editors who know their IP inside out.

I’ve interviewed a few authors who have done spec-work for fiction tie ins like Warhammer, Pathfinder, Forgotten Realms, etc. Some have found it actually rather fun to just step into someone else’s world, some like the challenge of trying to tell something unusual in a well-established setting and a few have found it constricting, or at least challenging. What was the experience like for you? Any unexpected surprises along the way?

Oh it was great fun, but a vertical learning curve. When they first invited me to write for them we talked and agreed terms and I confessed I knew nothing about the setting so they sent me reference material. Over 1Gb’s worth of it! The setting is so incredibly detailed it blew my mind. My first story, “Baphomet by Night,” centered on logistics and how the platoon of Imperial Guard relieving a occupation position had been left the wrong sort of ammunition for their weapons. My editor immediately told me what was wrong with that, and how the regiment my guys were relieving wouldn’t have used that sort of ammo, and which to change them to! I bow with respect to people who can retain that level of detail of any setting.

Well, they DO have a giant team, and now over a generation of development, behind them! Returning to the far more intimate level of world-building that brought us into this interview, now that Priest of Gallows is almost here, what’s next for Peter?

Well, my War for the Rose Throne “trilogy” is a quartet now, so the main thing is the fourth and final book in the series, Priest of Crowns, which should be out in 2022. After that… we’ll see.

Fantastic interview. Thanks for delving into the mechanics of writing too.