Eternity vs. Infinity: Isaac Asimov’s The End of Eternity

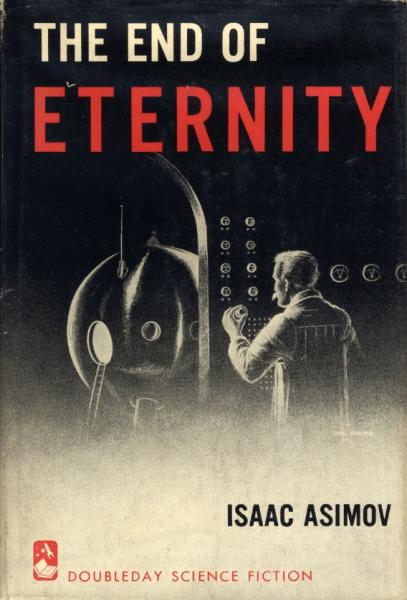

The End of Eternity by Isaac Asimov; First Edition: Doubleday, 1955.

Cover art Mel Hunter.

The End of Eternity

by Isaac Asimov

Doubleday (191 pages, $1.95, Hardcover, August 1955)

Cover art Mel Hunter

Just as Arthur C. Clarke’s The Deep Range, which I reviewed here last time, was one of the latter novels of Clarke’s early period (which I defined as everything from his first novel Prelude to Space in 1951 to 2001 in 1968), so is The End of Eternity one of the latter novels of Isaac Asimov’s early period (which I’ll define as everything from his first books I, Robot and Pebble in the Sky in 1950 through the 1960s, before Asimov “returned” to writing science fiction with the first of his later novels, The Gods Themselves, in 1972). (We can see that Asimov’s and Clarke’s early and later periods were virtually contemporaneous, since Clarke also “returned” to SF with Rendezvous with Rama in 1973.)

In Asimov’s case we can count 18 novels, or novel-like short story cycles, from I, Robot in 1950 to his novelization of the film Fantastic Voyage in 1966. Of these 18, however, four are story-cycles (I, Robot and the three Foundation books), six are short YA novels (the Lucky Starr novels, from 1952 to 1958), one is a non-SF mystery novel (The Death Dealers aka A Whiff of Death in 1958), and one is that movie novelization. That leaves only 6 proper SF novels, written as novels. The first three are his “Galactic Empire” novels: Pebble in the Sky; The Stars, Like Dust; and The Currents of Space (by far the best of the three), from 1950 to 1952. Two others are his early robot novels: The Caves of Steel and The Naked Sun, in 1954 and 1957. And the sixth one, the penultimate one among these six, is The End of Eternity in 1955.

I don’t have a citation at hand, but it’s been commonly regarded that The End of Eternity is Asimov’s best novel. This may be because it can be read as a stand-alone, not part of any series (though in later decades it’s been retroactively shoehorned into the Galactic Empire and/or Robot/Foundation series into which Asimov seemingly tried to knit everything), and it’s on a strikingly different theme from any of the series novels. It’s a recomplicated novel about time travel.

But it’s also a novel that undermines its premise at the end, transforming one kind of human history into another, in a way none of his other early novels did. And on if only on that ground, I’d agree that The End of Eternity is his best novel (at least of the early ones).

Gist

Time travel has been discovered in the 27th century, enabling an organization of Eternals to send agents back and forth in time to identify and implement changes for the betterment of human society. Technician Andrew Harlan violates the Eternals’ Basic Principles by falling in love with a subject in a future century. A central issue of the plot becomes a “bootstrap” maneuver, a la Heinlein’s “By His Bootstraps,” by the Eternals to bring themselves into existence. Then a mystery about the inaccessible “Hidden Centuries” resolves with the discovery of an era of humans working to destroy Eternity, because refining history endlessly has stifled human growth, including expansion into space. Andrew Harlan helps them succeed; and so with the “end of Eternity” comes the “beginning of Infinity.”

Take

Much of this novel consists of the familiar, almost overwrought, recomplicated situations familiar from most of Asimov’s novels and short works (virtually all of which are mysteries or puzzles to some degree, the most prominent exceptions, like “The Ugly Little Boy” and “The Bicentennial Man,” being his most popular stories), and its depiction of future centuries of Earth is overly-simplistic. Still, the novel’s complexities are intriguing, there’s greatest inventiveness in imagining the roles of the various Eternals and how they assess and manipulate time, and the novel’s final development identifies and confronts a larger issue to humanity than the vagaries of its plot.

Read-Through Summary with [[ Comments ]]

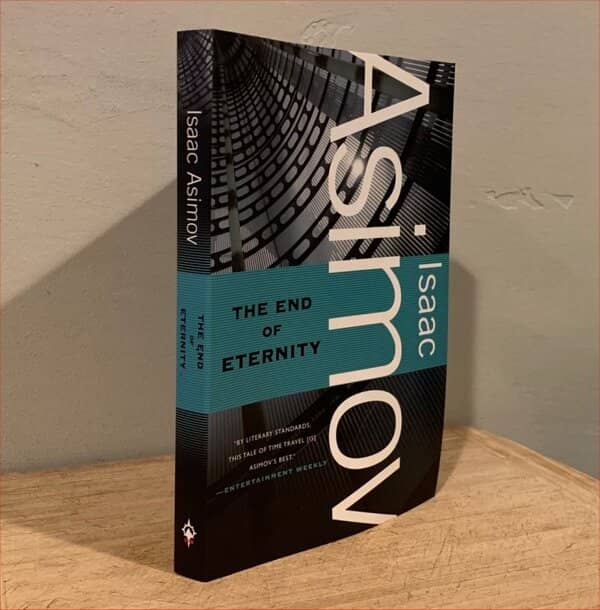

Page references are to the 2011 Tor/Orb trade paperback edition, shown below.

The End of Eternity by Isaac Asimov; Tor/Orb 2011.

Cover art JupiterImages.

- Technician

- Andrew Harlan is a Technician, one of a group of Eternals who travels in time, though they are limited to anything forward of the 27th Century. He enters a “kettle,” a chamber like an elevator that goes up and down time, that moves him from the 575th (century) to the 2456th. There he meets a sociologist, Kantor Voy, about a projected Reality Change. Harlan has detected a problem with Voy’s proposed solution, in that it involves the deaths of many people; Harlan thinks the same effect can be done by simply moving something on a shelf on a spaceship.

- We gather the background and set-up. The Eternals are to manage societies of humanity over the ages by making changes in one place to affect changes in others, even if it means wiping people out, or altering their personalities, as it’s put. (Playing God would not be an unfair take.) They speak in terms of MNC, Minimum Necessary Change, and MDR, Maximum Desired Response.

- Harlan and Voy enter a room with two screens, one watching the engine room of a spaceship, at a future spaceport. The intent of the planned change is to reduce addiction in some era; the price to pay is the destruction of the invention of the electro-gravitic ship in the 2481st.

- Voy concedes Harlan’s insight. Harlan agrees not to mention Voy’s oversight, if Voy will help him check something about a woman, Noÿs Lambent. Harlan reflects that the problem with Eternity involves women, and not only is he willing to ruin Eternity for Noÿs, he has the power to do it.

- [[ More 1950’s sexism in a moment. Also: Asimov’s characters are always bristling at each other. Does this reflect the academic environment Asimov spent time in? Subtle rivalries? Jealousies? ]]

- Observer

- Now we flash back as Harlan recalls the Basic Principles, the four parts in the life of an Eternal: Timer, Cub, Observer, and Specialist. The first is before being recruited, at around age 15. Then one is a Cub for some amount of time; then an Observer of various eras to identify things to change; and finally a Specialist to actually implement the changes.

- Eternity began in the 27th; everything before that is fixed.

- Harlan reflects on the problems of the 482nd, p25-26, which is “hedonistic, materialistic, more than a little matriarchal,” and where the intent is to correct this to create “a branch in which millions of pleasure-seeking women would find themselves transformed into true, pure-hearted mothers.” [[ This was the mid-1950s, and aside from the sexism that presumes females should be only mothers, it begs the central thesis of the novel about who makes the decisions of what to change. ]]

- Meanwhile Harlan’s hobby is to study Primitive history, everything before Eternity, that cannot be changed (and which happens to include our own 20th), by reading books.

- Harlan, as an Observer, works with assistant Computer Finge (who doesn’t like him) and one day is introduced to Senior Computer Twissell — a “legend, a living myth” — who is impressed by Harlan’s analyses. (Twissell smokes cigarettes, which are approved of hardly anywhere in history, we’re told. [[ Asimov, in his memoirs, described his distaste of cigarettes and smoking. ]] ) Harlan is invited to be Twissell’s personal Technician, which surprises him, but with the specific assignment to teach a particular Cub everything about Primitive History. Finge can’t explain completely, but he claims the assignment is to protect the very existence of Eternity.

- Cub

- The Cub is B.S. Cooper, from the 78th, who was recruited at age 23, unusually old. He even has a wife! Harlan gives him a book to read. Cooper seems to have a resentment against Technicians, who are said to be cold and calculating.

- Twissell invites Harlan to go out on an MNC, to the 223rd. All he has to do is jam a car’s clutch, to avoid a war. It’s Harlan’s first job as a Technician.

- A year passes, and Harlan’s reputation grows, as a wonder boy, never-wrong.

- One day Harlan has to check something in the 3000s and the Cub B.S. Cooper asks to go along. Sure. They both enter the kettle. They talk about how Eternity will never end, at least until the sun goes nova; and about the Hidden Centuries that can’t be entered. But upon their return, they are met by Twissell, who is very angry that Harlan took Cooper on such a trip. His job is only to teach!

- Computer

- After another year Harlan re-enters the 482nd. He’s changed in two years, become withdrawn. He’s here to meet Finge again. There’s a new crisis in the 482nd and Harlan is needed to Observe. And he’s introduced to a girl! A beautiful girl from the local century, Noÿs Lambent. Her presence makes him angry; she’s a distraction. Women are bad for morale. He demands of Finge that she be returned. Finge wonders if Harlan has ever had a girlfriend… No. Liaisons with Timers are discouraged. Harlan is aware of such arrangements but thinks of them distastefully. He reflects on how the Eternals are like monks, who have a higher mission.

- One day the woman speaks to him in the corridor and he angrily snubs her.

- Then Finge explains his mission involves living in her dwelling! Something about studying the local culture to see more about the Eternals than they should…

5, Timer

- He comes to her estate outside the city. The upper classes in this century are called “perioeci.” Wealth is unevenly distributed, near the point when intervention may be necessary. Staying with her, he lives in luxury. He dreams of the Allwhen Council, with Noÿs there.

- He wakes, dresses. She’s slightly confused that the month has changed. Has she lost three months? No, silly girl.

- He takes notes on a “molecular recorder” about conversations he hears. She wonders why he’s angry with her. She brings him another drink. She wonders how old he is. Won’t he live forever? He finds himself more affected by her. Why are there only male Eternals? Some reason involving the relative impact abstractions of men and women. He can’t tell her any of this. She asks him to make her an Eternal. His head whirls. Finally he can’t help himself; they embrace. She shares his bed. He thinks he has some glimpse of understanding, but it escapes him. Something about the Cub. He realizes there’s some terrible secret he was not meant to know…

- [[ I’m pretty sure this is the most prominent female character in all of Asimov’s early period novels. This seduction scene however reads very weird, as if the character, perhaps like Asimov himself, who’d married in 1942 but didn’t have much other experience with women to this point, didn’t really understand how these things worked. ]]

6, Life-Plotter

- A month later, he’s back to ‘now’. He stages the intervention he described in chapter 1: he appears in the engine room of the spaceship, and moves a container from one shelf to another, then returns. ‘Now’ the spaceport on the other screen is rusted and decrepit; the electro-gravitic space drive has been removed from history.

- He visits Life-Plotter Neron Feruque, who uses a Summator to plot all possible lives of Noÿs Lambent. Meanwhile they chat about all the requests for anti-cancer serum. They can’t all be granted; what if they *all* lived…? The Eternals can’t save everyone.

- Later he ponders what the Change will be that affects Noÿs’ world. He deduces it must involve her class, therefore her. She would not be the same.

- He returns to the Life-Plotter, who tells Harlan that she won’t exist at all!

- — and Harlan feels joy!

- [[ Notes as reading: Are there hints here of a parallel group of time travelers? One that manipulates the Eternals? Also note 79t about the futility of space travel, see quote below. ]]

7, Prelude to Crime

- He goes up in the kettle.

- He recalls Finge coming to his room to speak, Finge noticing Harlan’s wooden bookcase. Finge claims Harlan’s report isn’t complete… so Harlan is obliged to tell of his liaison with Noÿs, and tells of his intention to apply for a formal liaison. He wonders if Finge is jealous? No. Finge explains calmly: the thing they’re trying to change is the superstition that Eternals are immortal, that she made love to him, an Eternal, so that she will become immortal too. So *he* was chosen as much as she was. Otherwise, why would she want a man like him?, Finge asks.

- But later Harlan recalls that Noÿs was Finge’s secretary for several months. Why didn’t she seduce him? Was Finge refused?

- He knows what to do.

8, Crime

- He goes to her, back in her estate, and tells her to do everything he tells her. They go upwhen, far, to 111,394, in the middle of the Hidden Centuries (hidden because they can’t exit into Time there). He questions her motives, and she denies believing the part about Eternals being immortal.

- The facility there is empty, but stocked; he explains about mass duplicators.

- Then he explains to her about variable reality — how reality changes by the interventions they stage, how their old worlds literally don’t exist anymore. Who are the Eternals to do this, she wonders, 115; the aim is to increase the sum of human happiness, 116.8.

- [[ This is an excellent question. Who decides? This is a thematic hole at the heart of this novel. Who decides what the sum of human happiness is, and what sacrifices to make here to make people happier over there. There are recent 21st century books by thinkers about this issue, e.g. by Peter Singer and Sam Harris, but others dispute them; there is still no consensus. And of course many religious groups would dispute this thesis for utilitarian human happiness, having very firm ideas about how everyone should live their lives. ]]

- They’re about to commit a crime, he admits. But he knows something that will help protect himself…

- [[ Note remark that time deliberately avoids paradoxes, 106.6: “There are no paradoxes in Time, but only because Time deliberately avoids paradoxes.” This echoes, IIRC, part of the rationale of Benford’s 1980 novel Timescape, which perhaps I’ll review here eventually. ]]

9, Interlude

- He returns to the 575th, where Twissell remarks that he’s “On the nose…” as if anticipating his return. [[ Is this another clue, that someone else is manipulating him? ]]

- He reacquaints with the Cub, who’s studying math. And is particularly curious about Los Angeles in the 23rd.

- Harlan does research, in Twissell’s reports, and looking for unexplained Changes. He discusses how different versions of art can’t be computed.

- And he loosens up with Noÿs. When she mentions that she misses her own books, back in her estate, he eagerly declares he will get them for her.

- So he returns to his estate, which should be empty — yet hears sounds of someone else in the house.

10, Trapped!

- He worries he’s been caught by Finge. But no — he realizes he’s seeing himself! He quickly backs away.

- [[ Asimov famously abandoned writing second drafts, as explained in The Early Asimov concerned one of his longer 1940s stories. I’m not sure if that was true for his novels, but scenes like this one suggest that Asimov was contemplating plot complications that he did not actually follow through on. ]]

- He resumes routine. He tries to return to Noÿs — but the kettle stops, stuck, at 100,000.

- He confronts Finge, armed with a neuronic whip; Finge says they know about him, he was being tested himself — and failed. Finge threatens to dispose of Noÿs by transporting her to some disaster, like an airplane crash, where her body would never be found, 142b. [[ Did this inspire Varley’s “Air Raid”? ]]

- [[ The “neuronic whip” is a prop in other Asimov stories and novels, such as Pebble in the Sky, which is a reason Asimov could belatedly retrofitt this novel into the entirety of his Galactic Empire and Foundation and Robot universes. ]]

- Harlan is determined to take his issues before the Allwhen Council.

11, Full Circle

- He tries to meet Twissell, who isn’t there. He goes to sleep, thinks. In the morning he’s summoned to an Allwhen Council session, where he has lunch with Twissell and five others. One of them brings up the subject of paradoxes, what would happen if a man met himself, with various scenarios about versions A and B.

- Harlan becomes frustrated and makes a statement. He knows about the Lefebvre equations that are the basis for time travel, discovered in the 27th; and yet Mallansohn supposedly invented time travel in the 24th. Did he discover them by chance?

- Or is the Cub being trained in mathematics to go back in time and teach them to Mallansohn?

- He’s told – no, the Cub *is* Mallansohn.

12, The Beginning of Eternity

- Twissel explains. The Cub is to be sent back to be Mallansohn and close the circle. He’s being taught everything he needs to know, as written in Mallansohn’s own journals.

- Harlan wonders if he can break the circle, and destroy Eternity.

- He’s taken to a room with a big sphere. There is more discussion about space travel; the suggestion is to eliminate all space travel in all eras.

- Harlan is locked in a control room. Cooper will be here.

13, Beyond the Downwhen Terminus

- The Cub Cooper is brought in the room, having been coached about what he needs to do in the past. The plan is to send him to 2317. But Harlan has an idea — he uses his weapon to smash the gauge. Cooper disappears, sent back into the past, but Harlan thinks his actions have wrecked the gauge so that, in effect, Eternity will end any moment now.

14, The Earlier Crime

- Harlan explains to Twissell about Noÿs. Twissel in turn explains that Finge hated *him*, and goes on with a long story about a woman, a liaison he had. He got her pregnant, had a premature son, and the mother died. He visited his son at age 30, then made a Change that left that son paraplegic.

15, Search through the Primitive

- They speculate how to reverse the Change and bring Cooper back. Could Cooper — sent to 1938 — have left a sign? They review news magazines of the era. Twissel knows nothing about the barrier.

16, The Hidden Centuries

- Dealing with a Maintenance man, Harlan and Noÿs both travel into the past. They discuss the lack of evolutionary changes; such changes only happen in response to the environment, p220.

- Speculation about reality changes, 221, and why haven’t evolved men come to exist in the Hidden Centuries.

- Harlan tries to show the barrier, but it’s not there. He finds Noÿs, and they return to the 575th.

- And he finds an ad, in 1938, showing the outline of an atomic bomb, with text spelling out ATOM, an obvious, unmistakable sign from Cooper.

17, The Closing Circle

- With 3 hours to go, Harlan and Noÿs travel to the past, appearing in a cold cavern. He explains, 236f, about how he was manipulated.

- He realizes it was *her*, recalling her words, how she fit 239.4

18, The Beginning of Infinity

- She admits that she is from an era of humans in the Hidden Centuries, who have been working to *destroy* Eternity. How even with Eternity, hyperdrive was developed, how man left earth, met other races, and eventually retreated… and eventually died out.

- What is the greatest good? 245m. Isn’t there an instinct for space travel, for expansion?

- Quote:

“They didn’t *just* die out. It took thousands of Centuries. There were ups and downs but, on the whole, there was a loss of purpose, a sense of futility, a feeling of hopelessness that could not be overcome. Eventually there was one last decline of the birth rate and finally, extinction. Your Eternity did that.”

- She explains that the problem with Eternity is its goal for the greatest good, which leads to static societies afraid of change and challenge. Which precludes space travel. The alternative is that mankind should expand into space *first*, and become the first galactic society. She explains how her people can view alternate Realities.

- And so letting go of this intervention will eliminate Eternity, but allow the Infinity of mankind’s advance into space. And they, Harlan and Noÿs, will remain here in the 20th century, and live happily ever after…

- And so: final lines:

With that disappearance, he knew, even as Noÿs moved slowly into his arms, came the end, the final end of Eternity. — And the beginning of Infinity.

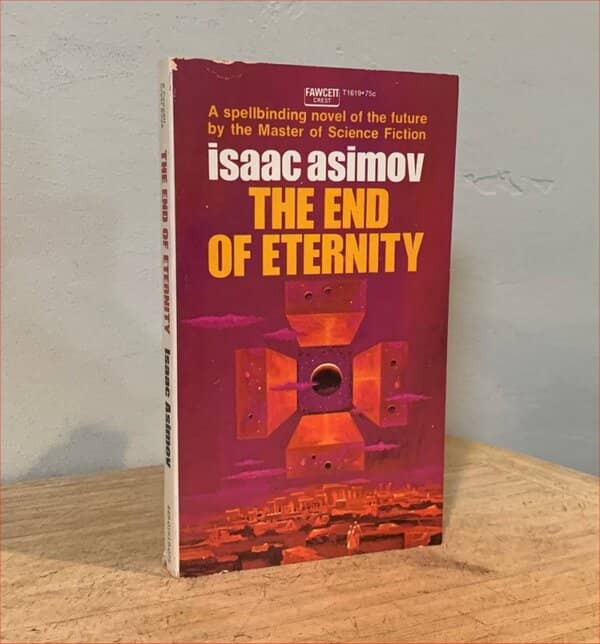

The End of Eternity by Isaac Asimov; Fawcett Crest, 1971

Cover art Paul Lehr.

Quote

Page 79t, about space travel.

“I wouldn’t regret,” he said, “having space-travel bred out of Reality altogether.”

“No?” said Voy.

“What good is it? It never lasts more than a millennium or two. People get tired. They come back home and the colonies die out. Then after another four or five millennia, or forty or fifty, they try again and it fails again. It is a waste of human ingenuity and effort.”

Comments

What struck me again, after not having read an Asimov in a while (I read The Naked Sun last August), is how Asimov’s prose and characterizations do not impress. They are very wooden. Asimov holds up less well, on these terms, than Clarke or Heinlein. (The Tor/Orb edition shown above has a blurb on the front cover from Entertainment Weekly: “By literary standards, this tale of time travel [is] Asimov’s best.” I have no idea what was meant by that.)

The attraction of the book, still, is how Asimov sets up a premise and then explores its implications with relentless logic and inventiveness. At the same time, that makes it almost a game, rather than a plausible drama or extrapolation.

The main theme here, about maintaining history through time travel, has been explored by many other writers. The first who comes to mind is Poul Anderson, with his “Time Patrol” stories, but I’m sure there are many others.

A simplistic flaw of this novel is how Asimov writes as if each century has a single style. All over the world.

The conclusion of this novel, the transition from maintaining and refining human history as a static society, to an open-ended unmanaged history, comes across as a conceptual breakthrough, of the type that characterizes the best science fiction.

In any case, this novel, as in the Foundation stories and “The Last Question,” presumes a vision of the future in which mankind expands throughout all space, to all the galaxies, that is almost repulsive to our 21st century perspective, considering our belated recognition of how humanity is destroying the biosphere of our one tiny original planet.

David Deutsch

It’s worth noting a tribute to this book by an actual scientist, David Deutsch, who’s written two eccentric but influential books, The Fabric of Reality in 1997 and The Beginning of Infinity in 2011. The latter book quotes, at the head of its last chapter, the final lines of this Asimov novel, thusly:

This is Earth. Not the eternal and only home of mankind, but only a starting point of an infinite adventure. All you need do is make the decision [to end your static society]. It is yours to make.

[With that decision] came the end, the final end of Eternity. –And the beginning of infinity.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of Arthur C. Clarke’s The Deep Range. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.

With Asimov the “idea content” of his fiction is often impressive but the “human content” rarely is. The End of Eternity is an extreme example of this, because in this book Asimov tried to portray a passionate, deathless love, and the result was a failure so pathetic it’s almost laughable.

I love these close reads of the classics! Great work, as always.

Even in in my most pro-Asimov phase, I had mixed feelings about this book. Harlan is such a colorless void of a character, for one thing; he’s no Lije Bailey or Magnifico Giganticus, that’s for sure. I was also tired of everything coming up Galactic Empire in his novels (and that was before he tried to retrofit the robot novels into the Galactic Empire setting).

On the other hand, Asimov was interested in what a Time Patrol was for. That was kind of interesting.

I give him points for ambition on this one, but a few years later he gave up writing fiction for decades (and his return to the field didn’t yield a lot of readable work). This leaves me thinking of Asimov as a writer of unfulfilled potential, which is weird, I guess. But there it is.

When I first read this book several decades ago, I was very impressed, thinking it was the ultimate time travel story.

When I reread it quite recently, I still found it very enjoyable, but not quite as impressive (alas, to lose one’s Sense of Wonder).

One line really cracked me up when one of Harlan’s colleagues describes Noÿs:

“You mean the babe? Wow! Isn’t she built like a force-field latrine, though?”

> “You mean the babe? Wow! Isn’t she built like a force-field latrine, though?”

Knut,

LOL! Oh, that cracked me up. When I first read this book (a the age of 14), I’m 100% confident I had no idea that was a future-refit of the old adage, “She’s built like a brick shithouse.”

Which (believe it or not) leering young men intended as a compliment, back in the day.

The End of Eternity leaves open several questions. Noys Lambent talks about letters that need to be sent. Just because she and Harlan are back in 1938 does not mean that humans will leave their planet without being nudged.

The special time travelling kettle vanished despite being within the field generated by an anti-change device. We weren’t told it was on an automatic recall. All of Eternity’s personnel have personalized anti-change devices to prevent them from being caught by change if they are out in the field. I presume Noys has one, too.

Cooper aka Mallansohn would also have had one. He could still complete his mission and publish the time travel equations.

I was left with the impression that Noys would be drip feeding Harlan information about changes that needed to happen. Perhaps bringing von Braun and those other nazi scientists back to the US was one such change.

Those time capable viewers in 111,394th would also still exist, because they had protection against temporal changes. If they had protected the Eternals area was Mass Duplication devices, they would have been able to recreate a work environment for Harlan to make any Changes they needed him to make.

I have to correct my own mistakes. Noys and Harlan went back to 1932. The time travel kettle was outside the protective field Noys had set up and vanished. I re-read the paragraph in which Noys stated her belief that Cooper would vanish along with his advert and Eternity, the Reality of her Century and the kettle would vanish (which it did).

Noys also said that she was trained for her mission like Eternity trained Cooper. Eternity did not tell Cooper everything. I don’t believe her bosses told her everything. I do not think those of her Century would have accepted being removed from existence. I think they would have protected the Eternity section area with its mass duplication devices with access to everything ever invented. Her Century would have need of that special kettle to send further information. I’m sure her Century would need to. They have to survive the Depression Era mid west of the US without any papers.