Fantasia 2020, Part XL: Fugitive Dreams

The Fantasia Film Festival usually runs around three weeks, but 2020 and its myriad of challenges meant this year’s festival lasted only two-thirds of that. Time moves fast, faster still during Fantasia, and so it came about that with a sudden shock I found myself in the final hours. I had three on-demand movies still to watch that I hadn’t gotten to, and only one on a fixed schedule, my first of the last day.

The Fantasia Film Festival usually runs around three weeks, but 2020 and its myriad of challenges meant this year’s festival lasted only two-thirds of that. Time moves fast, faster still during Fantasia, and so it came about that with a sudden shock I found myself in the final hours. I had three on-demand movies still to watch that I hadn’t gotten to, and only one on a fixed schedule, my first of the last day.

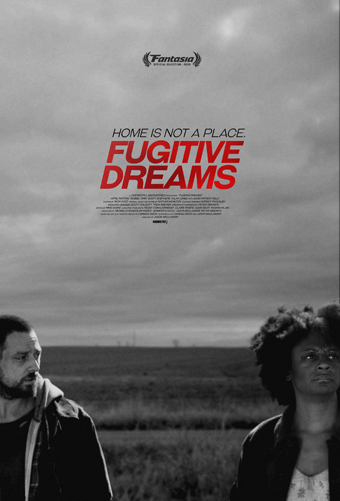

That film was called Fugitive Dreams, and it was directed and scripted by Jason Neulander from a play by Caridad Svich. It opens in an abandoned gas station where a Black woman, Mary (April Matthis) is about to slit her wrists in the ladies’ room. At which point a White man named John (Robbie Tann) bursts in, grabs some toilet paper, and almost incidentally stops her suicide attempt. The two of them, neither entirely mentally healthy, become squabbling comrades as they set out across what appears to be an empty midwestern America, sometimes riding the rails like hobos in old movies.

The exact era of the story’s difficult to pin down; after drive-in movies have been around a while, but probably before cell phones and the internet. On their journey John and Mary meet other drifters, including the menacing Israfel (Scott Shepherd) and his mute mother Providence (O-Lan Jones). Interleaved with this story are dreams, visions, and memories — along with lies and questions, notably about John’s background and parentage. It all makes for a surreal road movie without a real destination.

Most of the movie is stunning high-contrast black-and-white, and it’s quite striking — like an older film in its lighting, but a modern one in its visual storytelling. Some dreamlike segments are in colour, and while they look fine, other than a recurring image of a poppy field none of them quite match the stark beauty of the wide-open monochrome spaces, or of a nighted conversation in a shuddering boxcar. The acoustic soundtrack’s a fine match for the imagery, emphasising the way the film aims at evoking classic Americana. Old movies are referred to in dialogue, a kind of imagined paradise for John, and the sense of a road-trip film is very strong.

So are the religious overtones, visible in the names of the characters, and in the choice of an abandoned church for the film’s climax. But to what end is less clear. The empty church echoes the empty landscapes of the film, and hints at the characters’ abandonment by God; if you see them as searching for the divine, it’s certainly a downbeat symbol. But it’s a little unclear what the characters actually are seeking. A home, perhaps, but that’s left underdeveloped.

This is not a movie that’s based around a tight, compelling plot. It’s instead a film more interested in subtext and symbolism. That’s a fine thing, but I found the symbols alternately opaque and over-general. There is a lot that can be read into the film, but little that makes a compelling through-line of meaning.

This is not a movie that’s based around a tight, compelling plot. It’s instead a film more interested in subtext and symbolism. That’s a fine thing, but I found the symbols alternately opaque and over-general. There is a lot that can be read into the film, but little that makes a compelling through-line of meaning.

The actors seem to understand the kind of film they’re in, and play to the subtext of their lines. That makes for some interesting effects, as they pull out emotional resonance not necessarily obvious from the scripted language alone. But the overall narrative suffers; there are any number of excellent performance moments, but I had difficulty seeing how one tied to another, or how they fit into the framework of the film overall.

In fact, for all the movie’s remarkable scenery and its framework of a journey, much of the film plays out in a series of conversations. A central colour sequence in which John meets a Quebecois trader (Twin Peaks’ David Patrick Kelly) is particularly static, but in general the story’s a sequence of talks between characters rather than actions. As a result, although it’s visually powerful and expansive, in its structure Fugitive Dreams still feels stage-bound.

This is odd, as the movie’s also interested in cinema and the experience of cinema. John yearns to find himself in the wonderland of Old Hollywood, and one of the more affecting elements of the film is its postlapsarian sense of that golden age of American film — which, like most golden ages, exists mainly in retrospect and in nostalgia. The movie’s own form, its use of black-and-white photography, becomes a knowing callback to a kind of movie that exists mainly in the mind: a paradise, a collective destination, “a place made up of other places.”

Still, as a narrative in itself, the film’s less compelling. If pushed, I think much of that is because it follows its least interesting character. We’re mostly centred in John’s point of view, drawn into his dreams and memories, encouraged to question his past. And he’s not an especially intriguing fellow. He’d be fine as a supporting character. But he lacks Mary’s strength of will and savvy, lacks Israfel’s demonic charisma, and lacks Providence’s mystery. I consistently found myself wanting the movie to spend more time on those characters, and less on John — or, contrariwise, to give John some reason or compelling trait to make him worth being at the heart of the film.

Still, as a narrative in itself, the film’s less compelling. If pushed, I think much of that is because it follows its least interesting character. We’re mostly centred in John’s point of view, drawn into his dreams and memories, encouraged to question his past. And he’s not an especially intriguing fellow. He’d be fine as a supporting character. But he lacks Mary’s strength of will and savvy, lacks Israfel’s demonic charisma, and lacks Providence’s mystery. I consistently found myself wanting the movie to spend more time on those characters, and less on John — or, contrariwise, to give John some reason or compelling trait to make him worth being at the heart of the film.

Fugitive Dreams is a lovely piece of work on the surface, a feast for the senses. And there’s clearly an attempt to dig deep and explore character-based subtext. But there’s a disconnect between the lovely surface and the subtext. The elegaic language is a bit too floral a bit too often. The conclusion is a bit too facile, a bit too symbolic. The movie’s not especially concerned with neatness of plot, but the ending comes off as too pat precisely because it chooses not to end what passes for a story. It resolves its symbols instead and is successful on that level; but symbols usually become more powerful the more concrete the story from which they grow, and I can’t help but think a more carefully-worked narrative structure might have made this intriguing work much stronger.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.