Tanith Lee’s Secret Books of Paradys

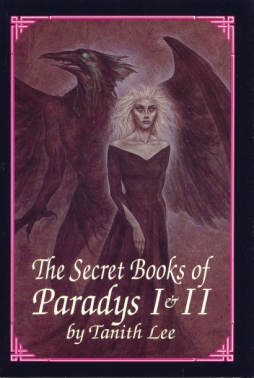

Women in Horror Month continues, and bearing that in mind I’d like to say a few words about Tanith Lee and the Secret Books of Paradys. Lee’s a prolific writer, and I haven’t read much else of her work — only the novel Heart-Beast besides the four volumes of the Paradys sequence — but after reading only the first Paradys collection, I started buying her work when I found it. Even a relatively small sample of her prose created a remarkable impression.

Women in Horror Month continues, and bearing that in mind I’d like to say a few words about Tanith Lee and the Secret Books of Paradys. Lee’s a prolific writer, and I haven’t read much else of her work — only the novel Heart-Beast besides the four volumes of the Paradys sequence — but after reading only the first Paradys collection, I started buying her work when I found it. Even a relatively small sample of her prose created a remarkable impression.

In some ways, as one reads through the whole series, it’s difficult to know how to take the books. They’re horrific, but also at times absurdly parodic or comic; which is to say grotesque. They’re oneiric, in that not only do supernatural events happen, but characters often act or change without obvious reason, and the fictive city of Paradys itself seems to accrue layers of meaning and complexity like a recurring landscape in a lucid dream. Above all, the books are weird with the weirdness of nightmare; though written with incredible technical skill, it’s difficult to articulate a single overall theme to the books, though multiple meanings suggest themselves.

Paradys is a city in northern France, originally a Roman settlement based around the exoploitation of soon-played-out silver mines. It developed over time into a major city, with a cathedral and taverns and damned poets and all the appurtenances of decadent gothic romance. The various stories of Paradys take place in different eras of the city’s life, told from different perspectives, using different styles. They’re linked by certain patterns of imagery — notably the ambiguous symbol of the moon — and a concentration on colour: each book, or long story, has a certain colour which defines it, and all colour-references within that story will refer either to white, black, or that specific hue. I can only imagine how difficult that technique is, but it’s incredibly effective at building distinct and distinctive atmospheres.

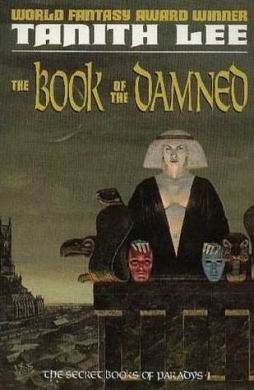

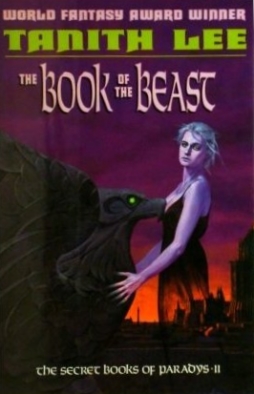

The first book, The Book of the Damned, consists of three novellas. The first, “Stained With Crimson,” follows a decadent poet in the 19th century who falls in lust with a mysterious beauty; the second, “Malice in Saffron,” is set in the Middle Ages (probably the 14th century), and follows a young woman who comes from the country to Paradys and, growing more brutal, becomes involved in heresy and art; the third, and briefest, is “Empires of Azure,” in which a writer and journalist investigates the murder of a transvestite stage performer, and his involvement with a sinister ancient force. The second book, The Book of the Beast, begins in a vaguely-defined period, somewhere perhaps in the 17th or 18th centuries, then skips back to present an inset story of Roman times before returning to its original cast of characters. The frame story is subtitled “Eyes Like Emerald,” while the inset tale is “From the Amethyst.”

The first book, The Book of the Damned, consists of three novellas. The first, “Stained With Crimson,” follows a decadent poet in the 19th century who falls in lust with a mysterious beauty; the second, “Malice in Saffron,” is set in the Middle Ages (probably the 14th century), and follows a young woman who comes from the country to Paradys and, growing more brutal, becomes involved in heresy and art; the third, and briefest, is “Empires of Azure,” in which a writer and journalist investigates the murder of a transvestite stage performer, and his involvement with a sinister ancient force. The second book, The Book of the Beast, begins in a vaguely-defined period, somewhere perhaps in the 17th or 18th centuries, then skips back to present an inset story of Roman times before returning to its original cast of characters. The frame story is subtitled “Eyes Like Emerald,” while the inset tale is “From the Amethyst.”

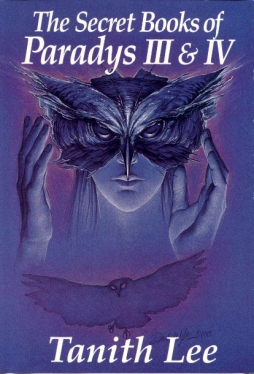

The third book is The Book of the Dead, a collection of short stories linked by the device of an unnamed narrtor giving a tour of a Paradys cemetary. Each story is occasioned by the tour guide coming upon a new grave. This book, subtitled “Le Livre Blanc et Noir,” has no colour beyond white and black. The fourth book, The Book of the Mad, is according to some Internet sources subtitled “Le Livre Orange,” though that’s not in my copy. It’s an intricate novel bringing together cities apparently of three different worlds. A girl in 19th-century Paradys falls in love with an actor; she is raped, goes mad, and is put in an asylum. In a 20th or 21st-century city called Paradis, an artist and writer is framed for murder and imprisoned in an asylum. In a city called Paradise, filled with lunatics and murderers, a brother and sister find a way between worlds — between Paradise, Paradis, and Paradys.

Collectively, the stories seem to get increasingly intricate. The connections between them are elusive, but notable. Leocadia, the artist in The Book of the Mad, wrote a book of short stories that seem to contain the tales of The Book of the Dead. The cathedral being built in “Malice in Saffron” recurs in the other stories, as do various other locations. The poet of “Stained With Crimson” is mentioned in “Empires of Azure.”

But, still, Paradys as a place is not defined by the kind of consciousness of history or continuity that one finds in a real-world city. There’s no sense of a community to Paradys. Institutions and politics are mostly notable by their absence. Even old families seem to exist only insofar as a given story needs them to; there’s no sense of a noble or wealthy clan or clans affecting the city as a place, as a historical entity that develops over time. Nor is there much sense of the city existing within a broader national or political context. One of the short stories sees a character journey to an analogue of Haïti, and there is mention of the Revolution in the form of the “Days of Liberty,” but there’s no real sense of Paradys existing within France as it actually is.

But, still, Paradys as a place is not defined by the kind of consciousness of history or continuity that one finds in a real-world city. There’s no sense of a community to Paradys. Institutions and politics are mostly notable by their absence. Even old families seem to exist only insofar as a given story needs them to; there’s no sense of a noble or wealthy clan or clans affecting the city as a place, as a historical entity that develops over time. Nor is there much sense of the city existing within a broader national or political context. One of the short stories sees a character journey to an analogue of Haïti, and there is mention of the Revolution in the form of the “Days of Liberty,” but there’s no real sense of Paradys existing within France as it actually is.

Which works in a couple of different ways. For one, on a practical level, there’s no real reason to assume that Paradys exists in this world at all. The multiple cities of the different realities of The Book of the Mad actually emphasise how removed from reality Paradys can be. Symbolically, Paradys is not a concrete, rational city that exists in conventional time: it is a nightmare, a city of the moon. It is a home for horrors, which summon pasts into existence as needed.

What sort of horrors live in such a place? There are vampires and bad angels and evil magic, but these monsters aren’t conventional. They’re not explicable, not reducible to a label. And not always the focus of the stories; these aren’t plot-oriented tales at all. These tales are about character primarily, but not characters easily defined by diagrams or conscious wants. I think these are dream-characters fit for the dream-city, characters that have to come to terms with the irrational within themselves, with irrational wants and unreasoning desires.

It seems to me that this comes about primarily as a function of transformation. State is not constant in Paradys. Things are always being made to become something other than what they were. Humans into beasts. Living into dead. Sane into insane, and back again. Above all, men into women and vice versa.

It seems to me that this comes about primarily as a function of transformation. State is not constant in Paradys. Things are always being made to become something other than what they were. Humans into beasts. Living into dead. Sane into insane, and back again. Above all, men into women and vice versa.

That above all, because these are also highly sexualised stories. I don’t find that sex and horror are conflated — the horror does not, on the whole, reside in the sexual aspect — so much as the sexuality becomes one of the keys to the unknown, the repressed, even the forbidden. It also becomes part of the grotesque over-the-top aspect as needed. Lee manipulates the atmosphere of the stories expertly, so that they can be dully bleak and then wildly excessive and even both at once; the sexuality of her characters, their understandings and fears and occasional startling lack of empathy, is very much a part of that.

But if sex in itself is not a thing to be feared in these stories, it is involved in the brutality that runs through them. These tales are genuinely dark, except, perhaps, insofar as they consciously venture into irony, if not self-parody. But irony itself comes to seem a limited, defensive stance. Terrible things happen to people in Paradys for no reason, and at length. You might expect as much from horror stories. But Lee doesn’t just fill these pages with bad things happening; she depicts characters reacting to these happenings in awful ways. Usually, it’s their lack of reaction, that lack of empathy I mentioned, that is most terrible. That lack implies something about their limits, about what they may have lost as a result of what they’ve gone through. They become, many of them, monsters: monsters of egotism. Like sleepers, dreaming, locked in their own skulls.

Each character is separate; each story has its own voice. That narratorial variety is one of the engaging things about the stories. There is frequently a lushness of diction, but in many cases — especially The Book of the Mad — a chill restraint. In this as in so much else there’s a technical precision to the storytelling, a union of tone and voice.

Each character is separate; each story has its own voice. That narratorial variety is one of the engaging things about the stories. There is frequently a lushness of diction, but in many cases — especially The Book of the Mad — a chill restraint. In this as in so much else there’s a technical precision to the storytelling, a union of tone and voice.

And what’s it about? What is this technique in aid of? As I say, I can find many thematic concerns in the book, but overall I think most prominent is a concern with art. Many of the characters are artists, poets, or storytellers. We find in “Empires of Azure” that the malign force that inspired events in that book is driven by the need to see events written, that there is a kind of magic in the telling of the story. That concern seems to be at the heart of much of the Paradys tales.

The use of colour, all the colours of the spectrum over the course of the stories, perhaps points to this as well. It’s obviously particularly relevant in the stories about visual artists. But it also emphasises the artificiality of all the Paradys stories — perhaps of all stories. All the stories, in their restricted chromaticism, are forcibly given the sense of a thing consciously told, consciously shaped. All the stories-inside-stories, the framing and intersecting of stories, all point to a consciousness of form and of artifice.

The last, longest, and most intricate story, The Book of the Mad, ends with unexpected optimism. Leocadia’s art provides some kind of salvation for herself and other characters. It is an awakening, and also a kind of escape from Paradys. Art can show us horror, and also reprieve us from that horror. It creates a parallel reality, into which we can enter. The Secret Books of Paradys emphasise, in the name of the series, the bookishness of the stories; also their hidden aspect, the obscured truth into which we can be initiated. They are, as a whole, not simply elegant (though they are that as well) but artful.

The last, longest, and most intricate story, The Book of the Mad, ends with unexpected optimism. Leocadia’s art provides some kind of salvation for herself and other characters. It is an awakening, and also a kind of escape from Paradys. Art can show us horror, and also reprieve us from that horror. It creates a parallel reality, into which we can enter. The Secret Books of Paradys emphasise, in the name of the series, the bookishness of the stories; also their hidden aspect, the obscured truth into which we can be initiated. They are, as a whole, not simply elegant (though they are that as well) but artful.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] Black Gate » Blog Archive » Tanith Lee’s Secret Books of Paradys […]

The Paradys books are possibly my second-favorite Lee series (the Flat Earth books being my hands-down favorites). They’re available in a single eBook omnibus edition, although for some reason the author is listed as “Tannith” Lee.

You might also check out her Veniss series (Faces Under Water, etc.), which is kind of similarly-themed.

I haven’t read these in 20 years. Loved them back then and am now tempted to seek them out again. Thanks.

Oh, and I don’t know it’s technically a subtitle, but there is a page in my Overlook hardcover of Book of the Mad that says, “Le Livre Orange”.

And the book itself is orange. Which suddenly makes a lot more sense to me …

Thanks for the comments!

Joe, I’ve got the first two of the Venus books. I’m holding off on reading them until I find books three and four. I’ll probably get them online at some point if they don’t turn up eventually.

And thanks for the news about the Overlook edition! I’ve got the collections from Guild America, which I think might have been done for the Science Fiction Book Club. Anyway, it doesn’t have the page in The Book of the Mad that yours does.

Yes, Guild America was SFBC — that’s how I have the first two volumes, but the third & fourth books I got as Overlook standalones.

Great article! These are indeed gorgeous, mystical, and artful stories. Joe’s right: the Vennis books are the perfect companion to the Paradys books–and every bit as superb. These two series, along with the Flat Earth series, would be enough to cement Tanith as a true master of fantasy–but she has dozens of other books that are just as amazing.

The only Tanith Lee I’ve read is A Heroine of the World, which I liked very much. Its title doesn’t fit it, and that mismatch between title and story seems to have adversely affected the book’s reception. Have you read that one?

Because I’m usually allergic to horror, I’ve only recently added Lee to my gigantic To Be Read list. Sounds like this series would be a good place to go next with her.

It took me a few attempts to get through Heroine of the World, but once I finished it I quite liked it.

I wouldn’t classify Paradys as horror but there’s definitely some gothic going on at the very least. If it turns out they don’t work, then I’d suggest going with something more overtly fantastical — the Flat Earth books, maybe (which I like to inaccurately describe as “Sandman in Zothique”), or Cyrion (sword & sorcery) or Sung in Shadow (fantasy retelling of Romeo & Juliet).

Thanks, Joe. It looks like Cyrion is my next destination, then.

Hi, Sarah,

I second Joe’s recommendation of the Flat Earth books–beginning with NIGHT’S MASTER. Also, Tanith’s latest epic fantasy trilogy was LIONWOLF–it’s also definitely worth checking out. I reviewed LIONWOLF for Black Gate in 2010: http://www.blackgate.com/2010/04/27/tanith-lees-lionwolf-trilogy/

And here’s my review on the Flat Earth trilogy (as reprinted in gorgeous new editions from Norilana Press): http://www.blackgate.com/2010/12/02/return-to-the-flat-earth-reviving-a-masterpiece/

Really, when you pick a Tanith Lee book, you can’t go wrong…

Enjoy!

And everyone should go order all of the new Norilana editions so that they continue with the reprints.

Joe: You said a mouthful… the Norilana editions are suberb collector’s items, and designed for gorgeous effect. I have all three of the core Flat Earth books that Norilana has done: NIGHT’S MASTER, DEATH’S MASTER and DELUSION’S MASTER. They even feature artwork by Tanith herself, and covers designed by her husband. I hope Norilana continues releasing TL books…

[…] The Secret Books of Paradys by Tanith Lee (review, Black Gate) […]