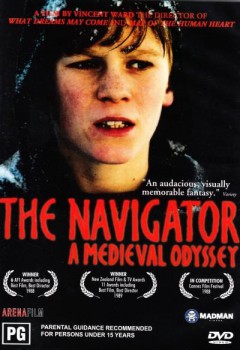

Adventure on Film: Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey

Under a fearsome black-and-white moon, a boy, perhaps twelve, enters a fever dream of  orange-fired torches whirling down infinite chasms, of men clambering up a towering church steeple, of skies moving too quickly for thought. The boy’s careworn, grubby face melts into black and white rippling water, and the nightmare — if nightmare it is — comes to a sudden end.

orange-fired torches whirling down infinite chasms, of men clambering up a towering church steeple, of skies moving too quickly for thought. The boy’s careworn, grubby face melts into black and white rippling water, and the nightmare — if nightmare it is — comes to a sudden end.

Welcome to Fourteenth Century Cumbria, a snowy, monochromatic waste, all bare rock and snowdrifts and blackwater lakes. In a hardscrabble mining village, young Griffin, plagued by his apocalyptic visions, waits for his idol, Connor, to return from a visit to the wider world. But even before Connor’s return, all talk is of death, for the Plague is come, marching inexorably closer. The villagers quickly convince themselves that only a holy quest can save them, and on the slimmest of evidence — Griffin’s disjointed prognostications — Connor, Griffin and four other men set off, bound for a mineshaft so deep (it is said) that it leads straight to the other side of the world. Griffin’s band brings a copper cross that they hope to mount to a titanic cathedral as an offering, a Cumbrian plea to stave off death itself.

Griffin finds the mineshaft right enough, together with a mechanical battering ram with which the men bore a hole to the far side of reality. And what do they find once there? Twentieth century New Zealand.

So begins Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey (1988), the most overlooked fantasy saga of the last thirty years, a grim and eerie hybrid that strafes any number of genres — horror, adventure, historical — without settling firmly on any particular one. File it, if you will, on the same shelf as Rod Serling, David Lynch, Donnie Darko and Nicholas Roeg. Think Don’t Look Now and Walkabout.

last thirty years, a grim and eerie hybrid that strafes any number of genres — horror, adventure, historical — without settling firmly on any particular one. File it, if you will, on the same shelf as Rod Serling, David Lynch, Donnie Darko and Nicholas Roeg. Think Don’t Look Now and Walkabout.

Indeed, Ward seems to be almost in thrall to Roeg’s disjunctive storytelling. Would that more filmmakers did the same! Whereas Hollywood proceeds day in and day out down the most linear of narrative structures, Roeg (along with Jean Luc Godard, Chris Marker, and a handful of others) proved that the plasticity of film lends itself to jumble, to an almost impressionistic smushing of images and time. Not that such a method would work in a more domestic piece, but here? Form follows function, and function follows form. Ward’s script trespasses into the world of recombinant art, and does so with disturbing, disquieting results.

Is there trouble ahead, you ask? Oh, yes. Not that ye need beware of dragons (all ye who enter here), but look not for levity, not in this fractured, danger-driven world where light itself is in constant danger of being forever extinguished.

Writer and Director Vincent Ward may be best known for committing to (and then walking away from) Alien 3, but he’s also had a hand in a number of other similarly fantastical projects, including What Dreams May Come and Map of the Human Heart.

Writer and Director Vincent Ward may be best known for committing to (and then walking away from) Alien 3, but he’s also had a hand in a number of other similarly fantastical projects, including What Dreams May Come and Map of the Human Heart.

He’s an elegiac director, intent on testing the limits of both reality and personal commitment. Film as a medium becomes collage, or even paint.

As for the characters in his films, they make bold promises, then do their level best to keep them, often at great cost. Neither survival nor happy endings are guaranteed. One can see with Navigator why Ward was attracted to the Alien franchise, and indeed, it was his work on this film that got him in the Nostromo’s door.

Speech becomes a character unto itself in Navigator, and the accents employed are thick, clotted, giving no quarter to those not already familiar with the dialects of Northern England. To be sure, not a soul living would be able to comprehend the speech of a true 14th Century Cumbrian, but Ward approximates by altering contemporary English until it sounds off-kilter, believably antique.

For example, definite articles are often eschewed entirely, such that when young Griffin talks of going to the village’s working mine, he says, “I go to pit.” We strain to hear the dialogue, yes, but it’s part and parcel of the hermetic Navigator experience; the effort required locks us all the tighter into Griffin’s visionary narrative.

For all its formal experimentation, the film places the value of basic story almost impossibly high. Can a dream, asks one of the characters, and the telling of it, save an entire village from plague?

For all its formal experimentation, the film places the value of basic story almost impossibly high. Can a dream, asks one of the characters, and the telling of it, save an entire village from plague?

Ward’s answer is an emphatic “Yes,” albeit with a grim caveat.

In physical form — that is, a DVD — Navigator has become quite the collector’s item. When it pops up on eBay, copies command sixty to eighty dollars. Netflix is no help; the copy I’ve put in my “queue” has been listed as “delayed” for months.

Amazon does not stock it, and so far as I can tell, it is out of print for U.S. audiences. However, do not despair. I got my viewing copy on interlibrary loan, and if all else fails, I believe the entire piece has been uploaded, in sections, to Youtube.

Track it down any way you can, adventure fans. This is a film not to be missed.

Onward.

Mark Rigney’s latest story for Black Gate was “The Find,” which Tangent Online called “reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… A must read.” You can see what all the fuss is about here.

Amazon has The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey (1988) listed as avaialble by DVD this April 2013.

I remember trying to describe this film when I’d just seen it in the theaters, and finding it nearly impossible to convey the mood and impact of the story. Any one-sentence description of the plot sounds goofy. There were times when I would have thought I’d dreamt the existence of The Navigator, if the friends I went to see it with had not found it as impossible to shake from memory as I did.

[…] Adventure on film: Navigator a Medieval Odyssey […]