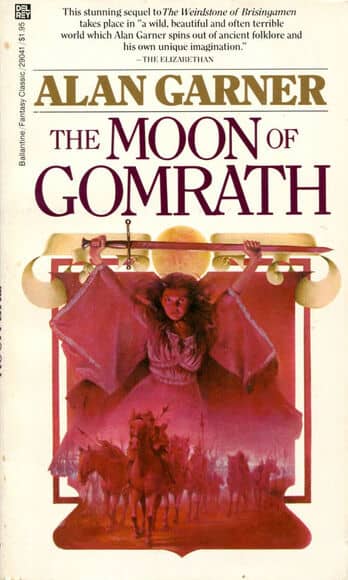

Doors Open, Doors Closed: Alan Garner’s Elidor

|

|

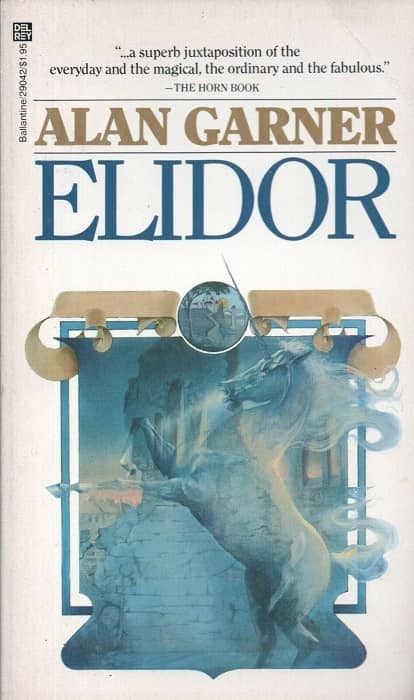

Elidor (Del Rey, July 1981). Cover by Laurence Schwinger

One of the best things about starting a book is that you can never be sure exactly how you’re going to respond to it, and those responses can range all the way from hurl the damned thing across the room hatred to toe-curling bliss, with all of a million subtle shadings in between. Every once in a while, though, a book breaks through even the upper ranges of enjoyment and appreciation and just absolutely knocks you flat, a reaction that’s especially powerful when you aren’t expecting it. That’s what happened to me when I reached onto the summer reading pile and came away with a book that I’ve probably had for twenty years or more without ever getting around to, Alan Garner’s 1965 fantasy novel, Elidor. It’s ostensibly a children’s book, but I’ve rarely had a more adult dose of fantasy.

Garner’s contributions to the genre have been few but intense, consisting of the Adderly Edge trilogy (The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, The Moon of Gomrath, and Boneyard), Elidor, The Owl Service, and (depending on your definition of the fantastic) Red Shift. The first of these books appeared in 1960 and the last in 1973. (The exception is Boneyard, which was published in 2012, almost fifty years after the second book in its group.) Since the mid-seventies, Garner has abandoned fantasy and devoted himself to essays, memoirs, and works based on English history or folklore. His fantastic fiction is a testament to the proposition that you don’t have to keep on doing something if you do it right the first time. (He has said that he resisted pressure to turn each book into a series because to crank out automatic sequels “would render sterile the existing work, the life that produced it, and bring about my artistic and spiritual death.”)

|

|

|

|

|

|

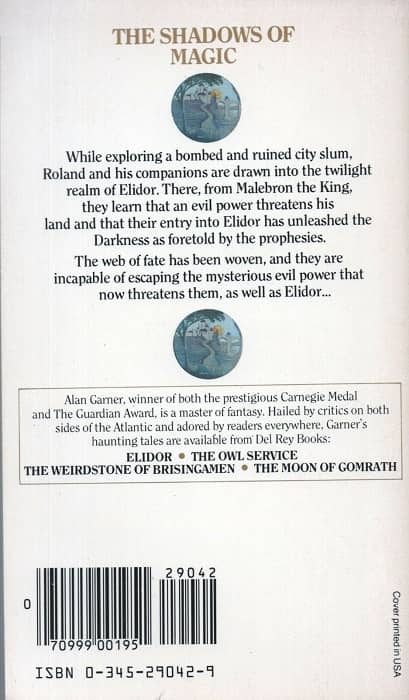

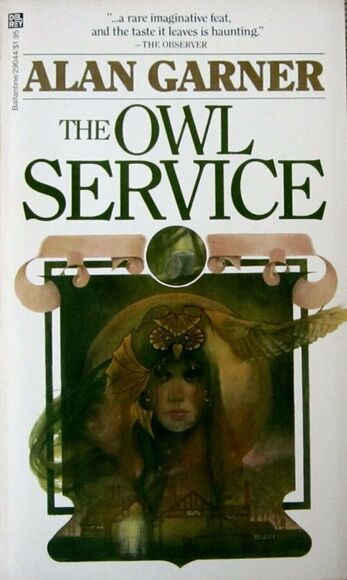

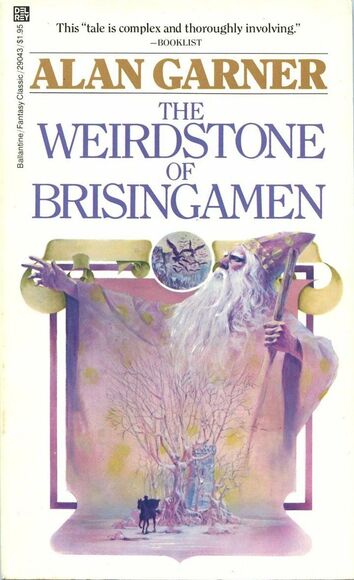

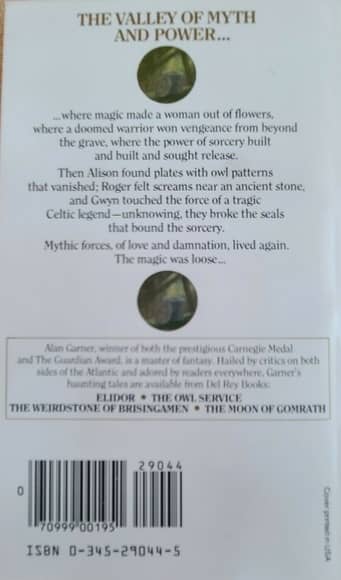

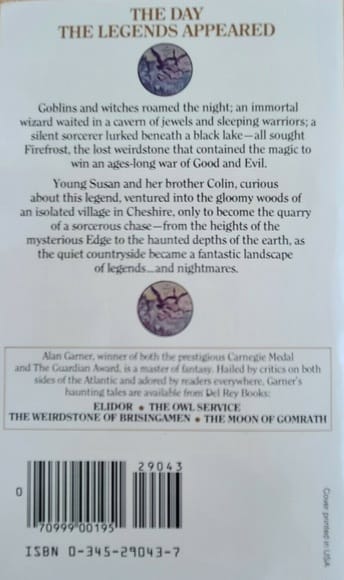

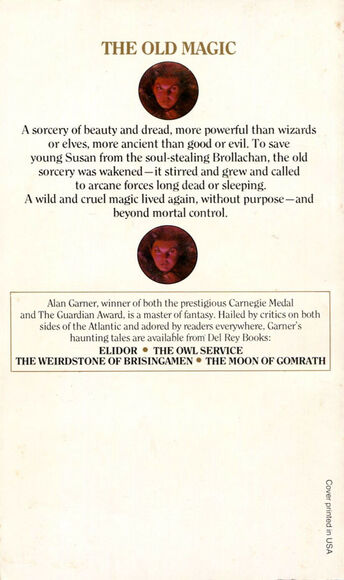

Del Rey Garner editions: The Owl Service, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, and The Moon of Gomrath.

July, September, and September 1981. Covers by Laurence Schwinger

Elidor concerns four young English siblings, Nicholas, David, Roland, and Helen. While on a day trip to Manchester they wander into an area of abandoned buildings slated for demolition and are soon lured to a derelict church by the tune of a mysterious fiddler. The children enter the building and discover a portal to Elidor, a medieval world of castles and forests and rugged seacoasts that is suffering under a kind of physical and spiritual blight. Roland, the youngest of the brothers, is the last to pass through and when he does, he encounters Malebron, the ruler of the land, who tells him that the children are key parts of an ancient, ambiguous prophecy and will be instrumental in bringing healing and restoration to the realm.

For that to happen, though, Roland must make his way into a secret chamber beneath a hill, a room in which the other children sit locked in an enchantment, silently gazing at a beautiful crystal apple blossom. Roland finds his brothers and sister and frees them by resisting the irresistible attraction and smashing the blossom that has held his siblings in thrall. (Though he seemingly arrives just a few minutes after his brothers and sister, they have been imprisoned for countless years, but without aging; like many faerie realms, Elidor’s time is different from our own.)

|

|

Elidor (Ace Books, 1970). Cover by George Barr

His brothers and sister freed, two more things must happen for Elidor to be healed. First, four objects of power (or “treasures”) vital to the life of the land – a spear, a cauldron, a sword, and a stone – must be taken into our world, where for a time they will be kept hidden (but not entirely safe – nothing in this tale is safe) from the forces that are corrupting the land. And lastly, the “song of Findhorn” must be heard – but Malebron has no idea who or what this Findhorn might be.

The children carry the treasures into our world (once here, they lose their magical “glamour” and appear as mundane objects) and bury them deep under the garden behind their house, both to conceal the objects and to mitigate the extreme electrical disturbances that the treasures apparently cause. Time passes, time during which three of the children begin to lose their belief in their extraordinary experience, and even their desire to believe in it, which is much the same thing. Only Roland still feels an attachment to Elidor, and he alone still feels responsible for the treasures.

Alan Garner

Eventually the enemies of Elidor (in the form of a pair of spear-wielding warriors) break through into our world, seeking to seize the treasures and also to destroy something else that has crossed over – Findhorn, who turns out to be a unicorn, fierce and untamed. The children (now restored to their belief in Elidor), enemy soldiers, treasures, and Findhorn all finally come together back in the ruined neighborhood where the adventure started, as the soldiers hunt Findhorn through the vacant streets and trash-filled lots. At last the wild, ungovernable creature sees Helen and walks meekly up to her, lying passive and peaceful at her feet (as in Medieval legends where only a virgin girl can tame such a magical beast)…which permits one of the warriors to drive a spear into the unresisting animal’s side. It is only then that the song of Findhorn is heard, a song which is nothing less than the unicorn’s death cry, a shattering sound that shakes the two worlds and sets Elidor free. In that final moment, the children can see the renewed Elidor shining through the dirty city windows that surround them, and in their pain and anguish they fling the treasures through them, back into the land they can never reach or even see again, back into the place whose life and joy they have saved but can never share.

Reading the last few pages of this relentless book is like having an enormous door slammed in your face with the force and finality of every door, everywhere, closing forever, leaving you alone in the dark, left out and cut off. It is a thunderclap of a conclusion, a powerful, shocking, utterly desolate ending that left me stunned and shaken.

|

|

|

|

First edition (Collins, 1965, cover by Charles Keeping), Amanda Lions (1980, cover by Stephen Lavis),

Magic Carpet (1999, Tristan Elwell), and Odyssey / Harcourt (2006, Greg Call)

Elidor blends elements of English, Welsh, and Irish myth, Arthurian legends, and C.S. Lewis-style children’s fantasy into an extraordinary whole. The story’s correspondences and even greater divergences from the Narnia books are especially notable. The children are like Lewis’s children in many ways, but unlike Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy, who were beloved of Aslan, these children scarcely exist to Malebron; in the end they are nothing more than tools that he uses and then discards, as Nicholas, David, Roland, and Helen eventually understand – to their grief. They have no ultimate share in the land that has called them, and they will not reign as kings and queens in Elidor; their fate is to be excluded. The far-off magical kingdom has been healed but they have been wounded for life, (and Findhorn is dead – like Narnia, Elidor demands a sacrifice, but unlike Aslan, Findhorn will not return in greater power and glory) and though Roland sees “the life spring in the land from Mondrum to the mountains of the north,” for him and the other children, “It was not enough.”

The cost of the victory has been too high. They receive no love or redemption from Findhorn; they only share in the agony of his death, and in this they understand the nature of Malebron’s callousness — nothing mattered to him but Elidor. In the book’s last, devastating line these four who have endured so much are left “alone with the broken windows of a slum.”

Elidor (Armada Lions, 1974). Cover artist unknown

This stark combination of mythic resonance and icy bleakness makes Elidor one of the strongest – and most ruthless – fantasy novels I’ve ever read, and its uncompromising honesty is uncommon in any book, much less one that is supposedly for children, where sugar-coating is often the rule. (I’d think carefully before I put it in the hands of a child, that’s for sure, especially a young one. The makers of the 1995 BBC series based on the book apparently thought the same – they contrived to give the story a somewhat upbeat ending.)

If there is a note of redemption in Elidor, it lies in the stringent beauties of Garner’s prose, and in the fact that for all of its harshness, the author’s vision is not cruel or gratuitous; instead, it’s bracing, like a doctor who respects you enough to tell you the unvarnished truth, no matter how unpleasant the news may be. Such unflinching courage and integrity are as rare in books as they are in people, and Elidor has a full measure of both. Its unsparing power ensures that it will be shocking and shaking readers of all ages for many years to come.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Science Fiction Catastrophe.

Novelist and critic Robert Nye reviewed Garner’s novel Red Shift, commenting “if we bear it in mind that Garner is deliberately employing the disciplines of writing for children to keep a grip on difficult material, like a man telling a ghost story in the most sceptical way he can, then we will better understand the extent of his success.” I grew up reading Alan Garner stories, in the 60s and after the heady pleasures of Brisingamen and Gomrath, found Elidor a difficult pill to swallow. Even more difficult was The Owl Service – this was the first book I ever read that I kept coming back to, in order to understand it. I read it and read it and read it, until I got what was going on. By the time Red Shift came out, I was an adolescent and was ready to take on its 3 parallel narratives and its searing emotional intensity. It remains my favourite among his works. I reread everything I could of Garner, some year’s back and found Elidor to be a pivotal work. I think all of his work is about how the mysterious, the supernatural, the numinous impacts on our every day lives. How there is the real world of the here and now living side by side with other worlds and how sometimes these other worlds drift into ours. There is a terrific moment in his little novel The Stone Book, where the heroine of the story is shown the route into a cave known only by her stone mason family and sees cave paintings and fossils from pre history. The later novels show people using shamanism or drugs to open up other worlds and experiences. The incursion of these other worlds is often shown as threatening and dangerous. As you rightly state, the exposure of this world to Elidor is not a happy one. When you expect to tumble into another world, sort out the politics to suit your own vague monarchical dreams and then live happily ever after, Garner’s vision will seem puzzling and bleak. Neil